Introduction

In a recent article on the FT George Soros harshly criticized foreign investment into China, pointing out the many risks that such a move might involve for investors and providing and indictment of what he perceived as worsening conditions of the “rule of law” in China, due to the regulatory crackdowns occurring in multiple industries.

In this article we provide a macroeconomic outlook for China, analyzing the merits of the criticism provided by Soros and the likely issues that affect China’s path to growth. We then provide our view of how investors should navigate China’s asset classes, explaining the issues and opportunities in China’s real estate, debt and equity markets.

The Macroeconomic Outlook

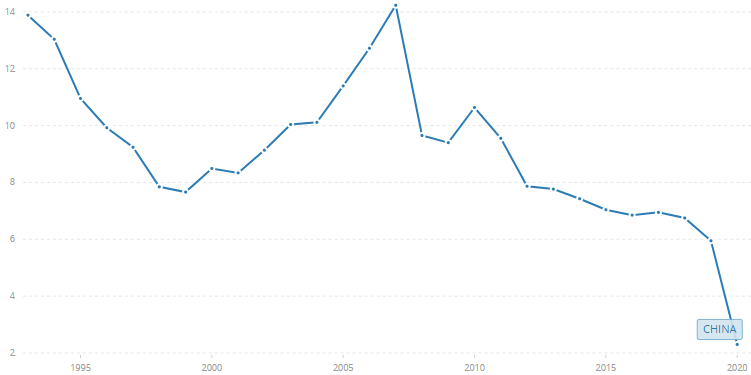

China’s economy for the past 30 years has been characterized by a high level of growth, often reaching the 2 digits. Following the GFC, the growth rate of the country rapidly plateaued to a much lower level over the next decade and a half.

Real GDP growth rate,

Source: World Bank

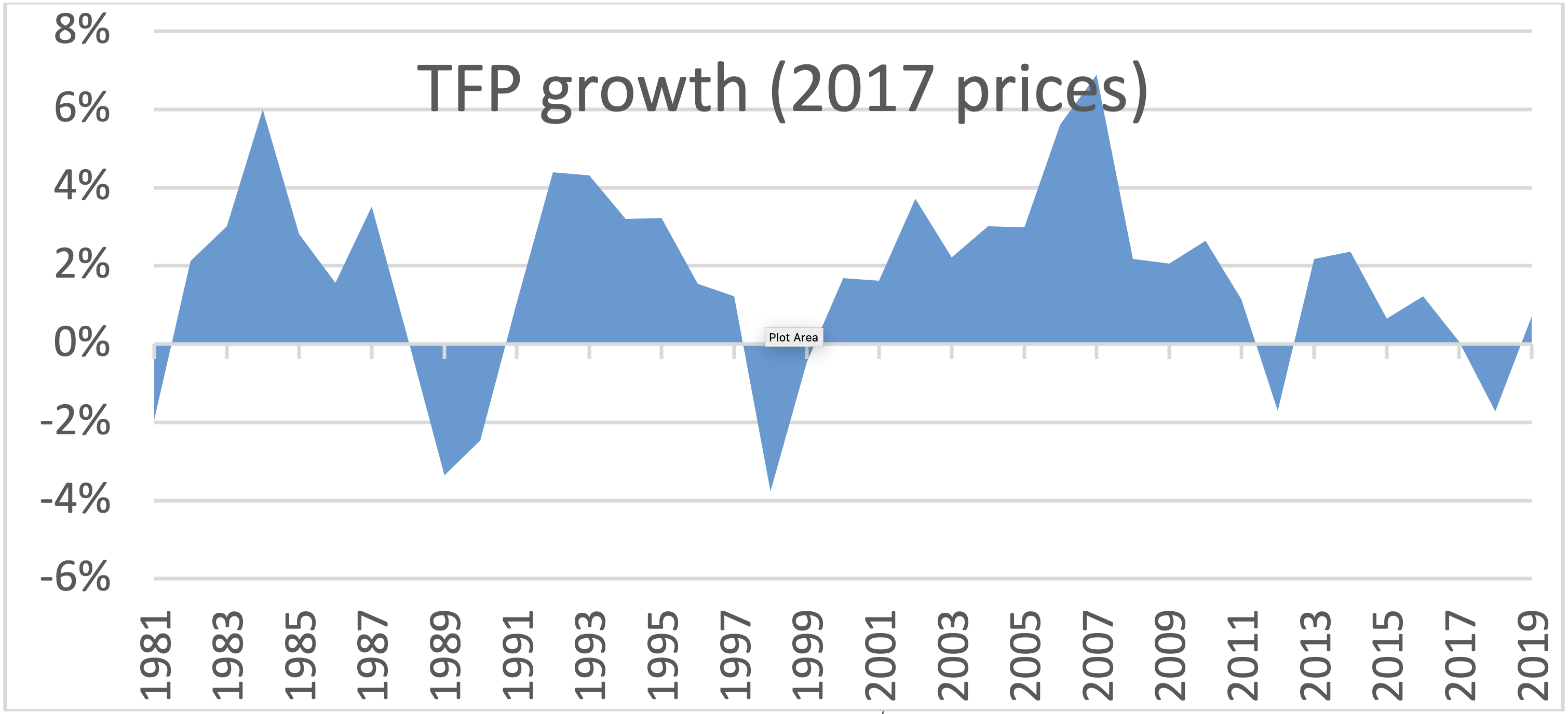

At the same time total factor productivity growth slowed down, again with a sharp decrease following the GFC.

Source: St. Luis Fed. Author’s calculations

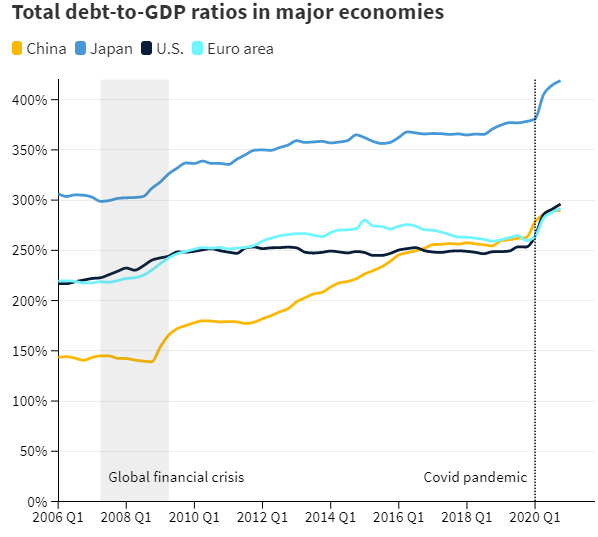

Moreover, again following the GFC, we observe one final major trend: a large increase in total debt to GDP, attributable mostly to large increases in corporate debt.

Source: bank of international settlements

In short it appears that Chinese growth following 2008 has been arguably unsustainable: Rather than being based on an increase in productivity it seems to have mostly derived from what at first glance seems to be unproductive, debt-driven “overinvestment” (Chinese Gross fixed capital formation to GDP has consistently climbed in the last 30 years to 42% as of 2020).

Our keenest readers might already be making a comparison with Japan the during and shortly before the first “lost decade”. Similar to China, fixed investment made up the largest percentage of the GDP and debt rapidly increased, followed by stagnation in TFP and growth. Many other data points add to this similarity: Rapidly increasing wages, high dependency on foreign trade and similar demographics. Yet we believe that this similarity does not imply a repetition of the Japanese 1990’s for China.

Japan at the start of the lost decade was at a far higher level of development compared to China, at certain points surpassing the GDP per capita of the United States. According to economic convergence theory, China, which has one sixth of real GDP per capita of the United States, would have far more room to grow. In addition, China can rely on far more natural resources than Japan, diminishing dependence to international trade, and it has far more geopolitical clout than the latter.

Having established this, we move to the main issues that might negatively affect China’s economic potential in the future and whether the “common prosperity” program can tackle these problems or not.

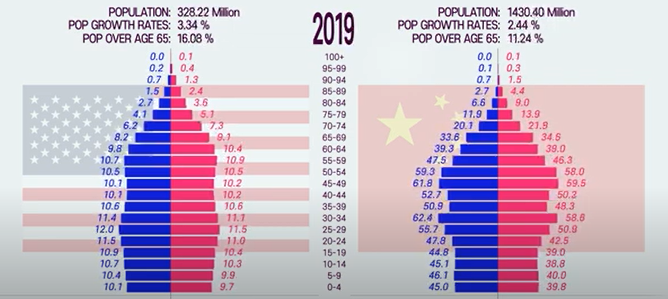

The first and gravest problem, which has also been directly pointed out by Soros, is the demographic issue. We have seen that productivity growth in China is declining, which has very negative implications for economic stability if the population continues to decline, as slack would not be picked up by productivity, resulting in the country being incapable of sustaining healthily the previously accumulated debt. In addition, a demographic crash would kill the real estate market.

Source: UN population prospects. Units in millions

From the above charts we can see glaring issues in China’s population pyramid. Not only its shrinking at a faster pace than the United States, but there is a large imbalance in the male to female ratio in the younger cohorts (up to 15% plus more males). As such we do not believe that in the medium term a good population distribution can be achieved: even if positive or coercive methods to increase fertility rates are enacted and they are successful, in the medium term the labour force will still shrink. As such China will necessarily have to rely on an increase in productivity, right when it has decelerated in the past few years, and will certainly have to increase the pensionable age above 60M/55F (50F for blue-collar jobs). We cannot predict whether China will succeed, but we can note how the 14th 5 year-plan has removed growth targets and instead focuses on a plethora of issues aimed at improving productivity.

The second issue is the imbalance between investment and consumption, namely the latter is too low, standing at merely 56% over the GDP. Curiously, this was also a problem in Japan’s 1990’s: Similarly to China investment took up a very large part of the GDP and consumption picked up during the lost decades, which might suggest that such a policy applied in China might perhaps be yet another indicator of upcoming lower growth rates. Indeed, XI Jinping’s “common prosperity” will focus on greater wealth redistribution, which in turn should spur higher consumption and bring balance to the economy. Given the very large amount of corporate debt held by Chinese firms, this increase in disposable income should even more strongly stimulate the performance of these companies.

The third issue is the possibility of an intensification of the trade war with the United States, which might involve other western powers in the longer run. This issue is also a “solution”, as diminishing trade with the rest of the world seems to play into the idea of refocusing domestically, but it certainly would involve disruptions in the short term. We believe that it is highly unlikely that tensions between China and the USA will ease, as elite consensus in both countries increasingly views the counterparty as incompatible, and Xi Jinping seems prone to risky adventurism in Taiwan.

This domestic refocus might imply changes in foreign exchange policy: as exports become increasingly less important, exchange targets might become more flexible resulting in higher volatility for the Yuan. In fact, volatility might increase also as a result of USA-China tensions. We want to clarify however that as of today, Chinese exports are still at record high levels.

The final issue, which we will however discuss later in the article, concerns China’s real estate bubble, and its consequences.

Before delving into how one should navigate China’s asset classes, we want to comment on the merits of Soros’s claim that foreign investors face unique risks. We indeed believe this to be the case and that the regulatory crackdowns are more than just “micro regulatory actions necessary to rebalance the economy” as certain pundits say as they seem to touch on issues which are certainly beyond the scope of regulators in western countries. Not only we expect these to slow down the development of the service sector, but they don’t bide well for investors… What sort of governance can the latter execute over Chinese companies if the government intervenes? And if, as mentioned, US-China relations deteriorate, what’s to stop both governments from sanctioning/harming investors? It is both in China’s and USA’s interest to ultimately cut dependence on each other and investors might be eaten in the crossfire.

Real Estate

Before analyzing the situation of the Chinese bond market, we want to give an overview of the Real Estate industry. We start from the importance of the Real Estate sector in the Chinese economy.

The following numbers could help in this regard:

- According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, in 2020, more than $2 trillion was invested in Chinese housing. More than twice the amount that was invested in 2006 in US, at the peak of the U.S. property boom

- In 2019, Goldman Sachs estimated that the entire market value of Chinese residential properties was $52 trillion, twice the size of the U.S. market and surpassing even the U.S. bond market.

- Research from RBA shows that from 2003 to 2017, real estate investment contributed on average 2% to GDP growth, about one fifth of the average increase in real GDP (10%)

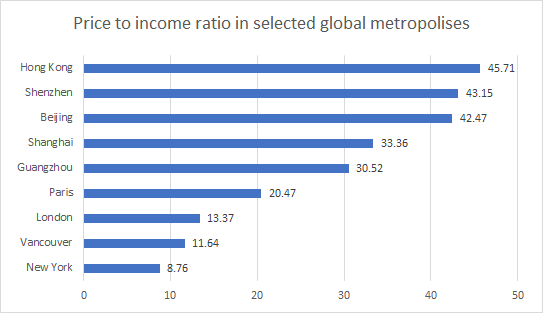

For the industry to reach the size of today, it is intuitive that Chinese house prices must have increased exponentially over the years. Indeed, prices relative to average incomes in Chinese first-tier cities are the highest in the world. From 1999 to 2016, the value of Chinese homes in China’s largest 35 cities increased by nearly sixfold and by more than eightfold in Shanghai and Shenzhen.

The key drivers of this exponential increase in house prices are: a rapid urbanization, a massive increase in income and savings of the middle class and a financial market that wasn’t very developed. Other reasons are for instance, the necessity of families to buy houses in good school districts to ensure better education for their children. Indeed, in China, many districts require families to own a home years in advance in order to allow children to have access to the school located in the neighborhood.

During the years, the State has always been present in the property market. Knowing what effect dangerous speculative elements could have on the housing market, the government has tried with little success to contain house prices through numerous policies. Nevertheless, we may now have reached a point in time where things are changing. The reasons are mainly three:

- With the development of China’s financial market, people will increase exposure to mutual funds and retail wealth management, this will likely squeeze out some of the liquidity previously allocated to the property market

- The Chinese government has understood that keeping using the property sector as a short-term tool to stimulate the economy is very dangerous as it would become more and more dependent.

- China’s property market is slowing and there is less demand for new apartments both due to the policies aimed to stabilize prices and to demographic factors

Is it too late? We think that speculation in the sector has gone too far and this will have an impact on the economy. Nonetheless, the scenario of a bubble bursting leading to a consequent recession does not appear that likely to us.

The Chinese bond market

Alongside Real Estate, China’s bond market has developed massively and it is now bringing serious concerns to the government about the effect that it would have on the economy if things go south in the property market. Real estate loans have increased to more than 27% of total yuan advances, from less than 20% a decade ago. Today, the Chinese bond market has a size of approximately RMB 120 trillion ($19 trillion).

Ratings in the Chinese bond market are dominated by a few domestic agencies. At the end of 2019, more than half of the market was considered “AAA ” and 99.6% of the Chinese bonds were rated “AA” or above. The underlying factors of this phenomenon are:

- The China Banking and Insurance Regulation Commission (CBIRC) has the authority to approve rating agencies and it directs banks and insurers to invest only in bonds rated AA or above. Indeed, issues that would fall below AA usually opt to remain “unrated”

- In evaluating creditworthiness, Chinese rating agencies place greater weight on the asset size rather than the potentially negative effects of leverage.

- Agencies inflate their rating to attract clients and are pressured to support government-linked groups

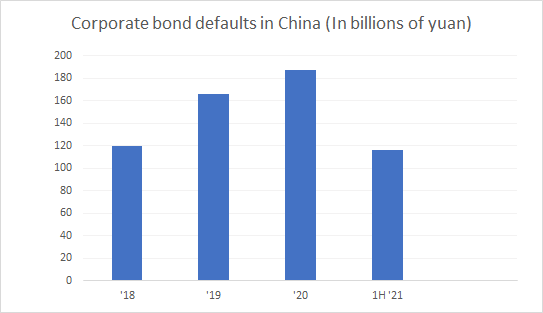

In recent years, China’s credit rating agencies have been criticized heavily for their triple A ratings on state-owned companies in the face of defaults. Criticism worsened after China’s local bond defaults surpassed RMB 100 billion for three straight years and is on its way for the fourth. However, in the next years we expect an improvement of the reliability of these ratings as central bank and the finance ministry have already urged credit agencies to change their rating models and the entry of international agencies such as S&P, Fitch and Moody’s in the Chinese market will provide greater clarity on the credit quality of Chinese bonds.

Evergrande

To understand the prospect of the bond market, it is useful to see what effect the collapse of Evergrande will have on the economy and whether it could pose a real systematic risk.

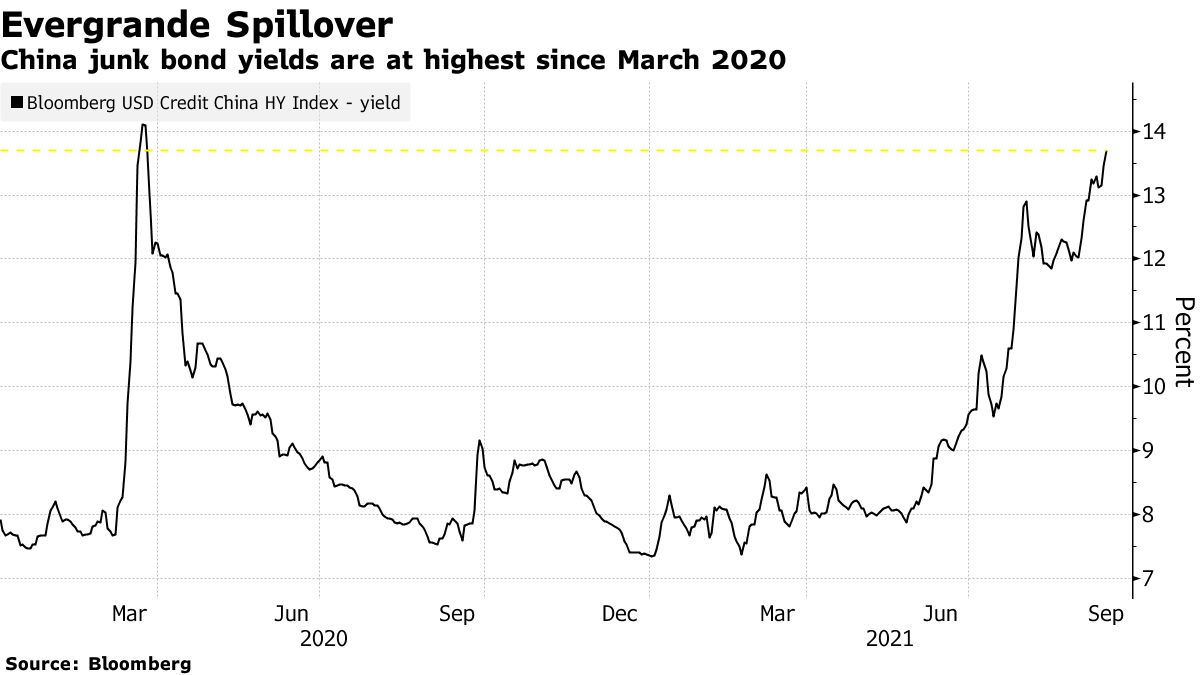

Evergrande, one of the largest Chinese property developers and the most indebted in the world, is sitting on more than $300 billion of liabilities and its liquidity is under tremendous pressure. As demand weakened and regulators started implementing new regulations, the already highly indebted company found itself in a liquidity crisis and its shares tumbled 80% in the last six months. Its bonds due 2023 are now at almost 30 cents on the dollar, while one year ago they were at 80. The company announced that it will not be able to pay its interest payments due this month, triggering trading suspension of its bonds in Shenzhen and Shanghai. Rating agencies see default “probable” as the company has $669 million of coupon payments due this year. Besides Chinese commercial banks, its investors include Allianz, Ashmore and BlackRock.

Serious concerns of a spillover effect on markets derive from the fact that historically, the Chinese government has always supported these types of companies at times of distress. To prove its commitment to reduce inequality and crackdown the industry, Beijing will be tempted not to save but it is aware of the serious damages to the trust of investors such action would have. This Monday, Evergrande denied that it would file for bankruptcy, instead, it hired Houlihan Lokey and Hong Kong-based Admiralty Harbour Capital Ltd. as financial advisers for what could be one of the country’s largest-ever debt restructurings. In fact, rather than a chaotic collapse into bankruptcy, we expect the situation to be solved through a restructuring led by its financial advisers and regulators. However, although the restructuring is a much better outcome than bankruptcy, we still believe that there is a contagion risk. Fire sales of Evergrande’s assets will probably have an impact on housing prices and spread panic among investors. With real estate accounting for 40% of household assets, even a 10% drop in house prices would meaningfully affect the wealth of citizens.  Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

Equities

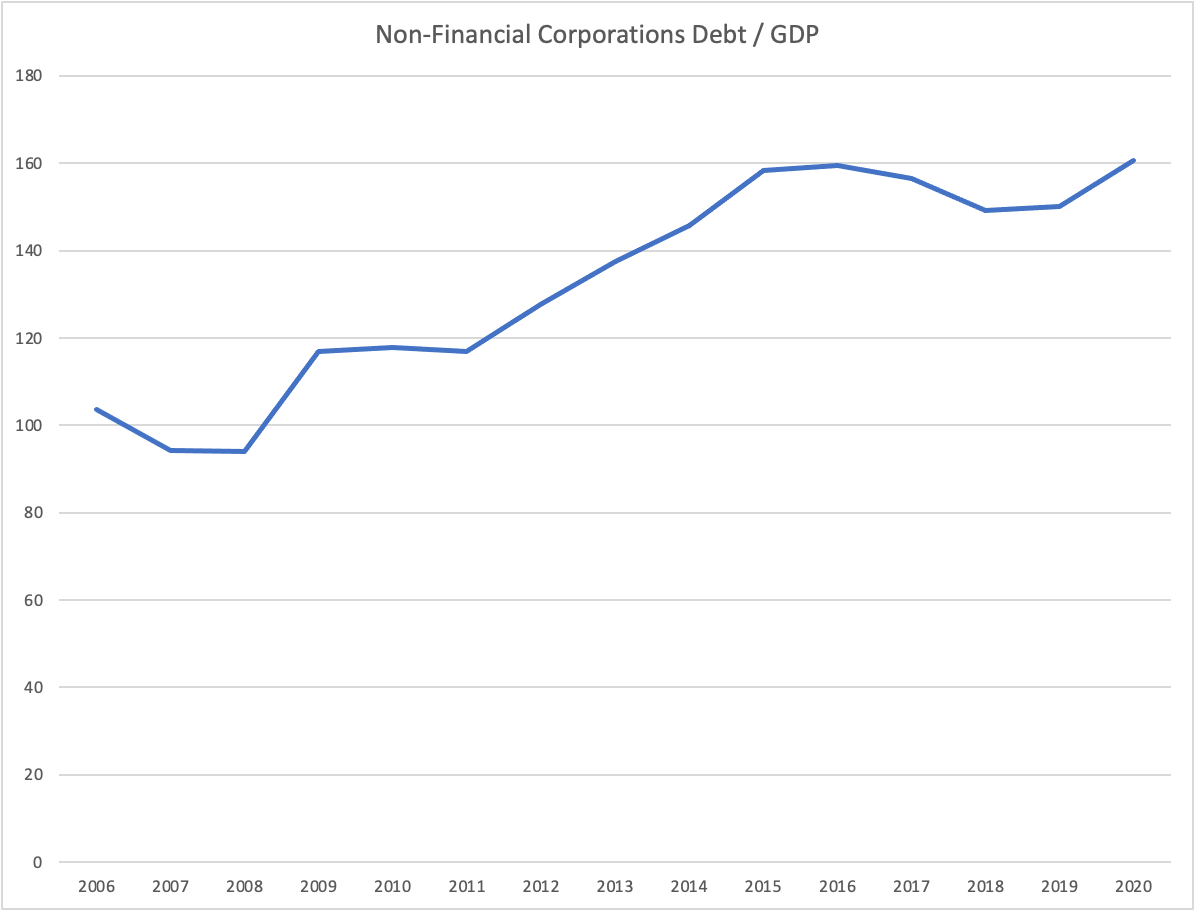

Our macroeconomic outlook shows that after the Covid crisis China is in a delicate situation. Since the GFC vulnerabilities have been building up in several sectors of its economy. In fact, China’s stimulus programme after the GFC supported non-financial corporations through lending from several State-Owned-Enterprises. Over time, this has led to a significant build up in non-financial corporation’s’ debt to GDP ratio, which now stands at 160%, close to its historical maximum and very high if compared to other countries, as shown in the figure below.

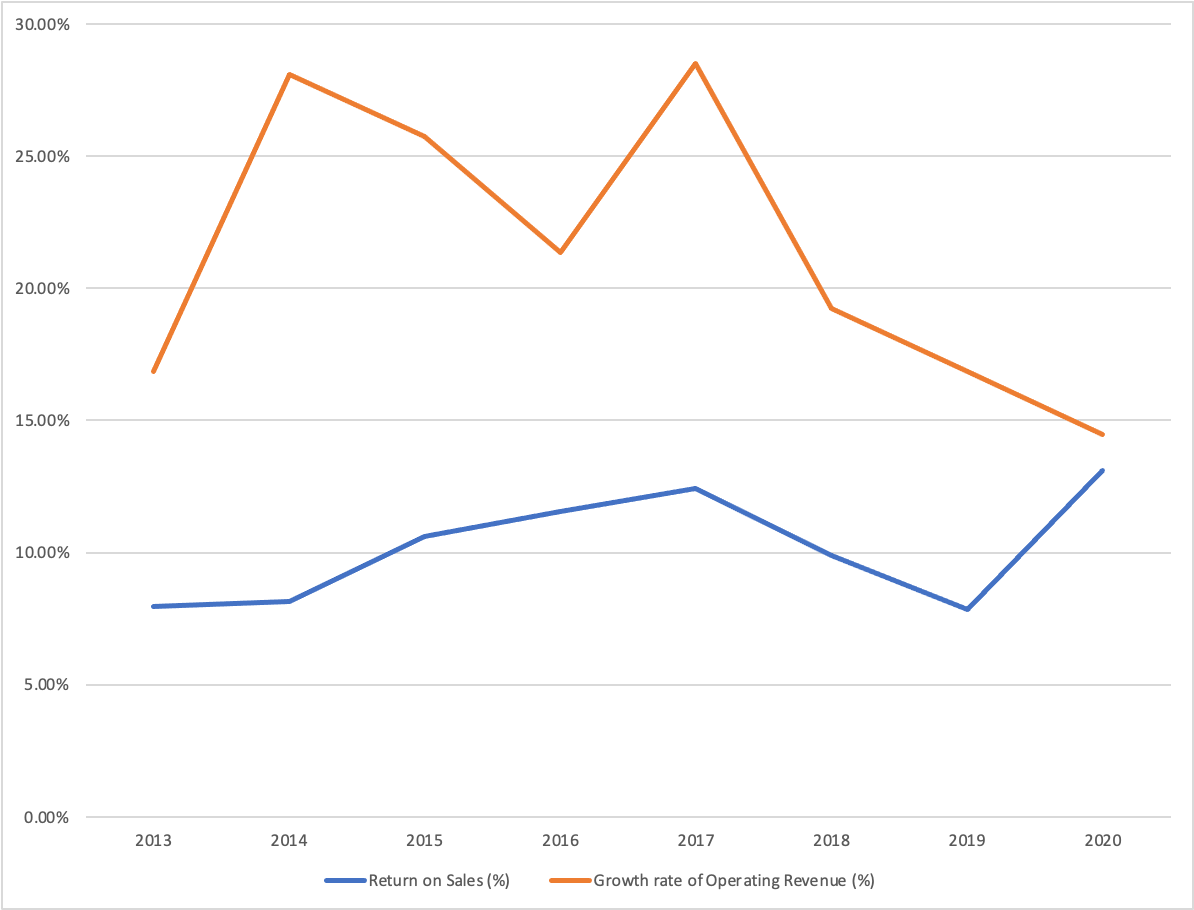

In this context, the Chinese government has undertaken important efforts to deleverage the economy, rein in speculation, and reduce financial vulnerabilities, especially those in SOEs. We can notice that these policies have impacted the GDP growth rate and consequently the growth in operating revenues as shown in picture below (which includes data for all Chinese companies listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen). Interestingly, we can notice that return on sales for Chinese companies have been increasing in the past 7 years. Probably, the main factor holding them down may have been the tendency of many American companies to outsource production to China to exploit its lower cost of labor. With the passing of time, this “arbitrage” opportunity has been shrinking, and thus Chinese companies have been expanding their margins. We can conclude that while the growth in operating revenues may have now stabilized at lower rates than in the past, Chinese companies have still much potential to increase their margins.

We now consider where equity prices in China currently stand with respect to their “fundamentals”. We start from the Gordon Growth Model which prices stocks assuming constantly growing dividends at a rate g, discounting them by the cost of equity capital r:

We decompose dividends as the product of earnings and the dividend payout ratio, and rearrange the equation as follows:

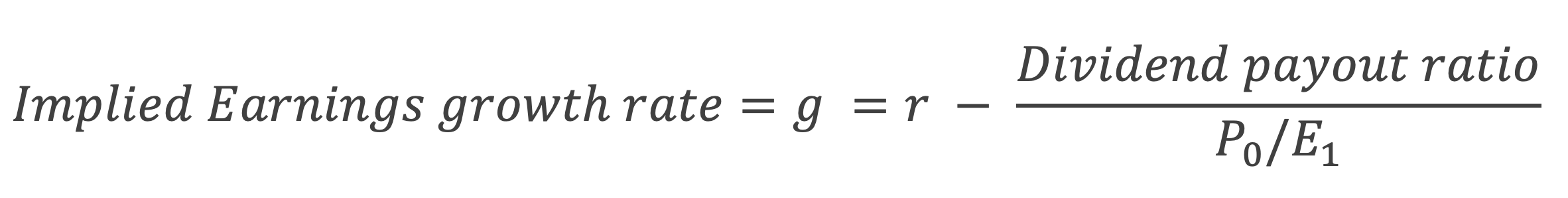

Then, we compute the earnings growth rate implied by the observed P/E ratio, assuming earnings growing at a constant rate g, a constant dividend payout ratio equal to its historical average, and a constant cost of equity capital equal to the sum of the risk-free rate and the equity market risk premium (adjusted for the country risk premium). The results and the P/E ratio are plotted in the following figure, data are referred to Chinese companies listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen.

Overall, the implied growth rate for earnings stands close to 5% slightly above the historical average of the past years. We conclude that Chinese equities are reasonably priced, and on the basis of their fundamentals, there may be some upside if the CCP manages to stabilize the country’s growth rate and margins of corporates follow.

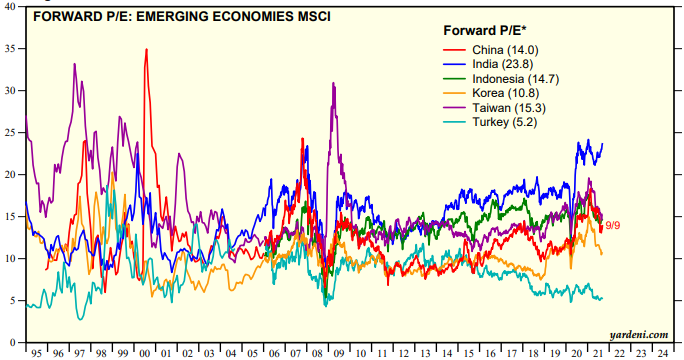

Finally, we compared forward P/E multiples with a selection of developing economies. As seen by the figure below, it appears that Chinese stocks are again priced right in the middle.

Source: Yardeni research

Source: Yardeni research

Nevertheless, we believe that it will be essential to actively calibrate the exposure of a Chinese portfolio to the different sectors of the economy with respect to the regulatory crackdown enacted by the CCP. So far, tech and education were the most adversely affected sectors, but the market expects the scope of the crackdown to increase. For example, shares of major aesthetic medicine firms have significantly underperformed, due to fears that these firms contradict the CCP moral values. The best strategy would be to simply avoid sectors which offend the morality of the CCP (ex. Gambling), while favoring firms which help China achieve its policy targets (ex. agricultural machinery/chemicals and infrastructure for developing rural provinces, security providers, renewables, electric vehicles etc.).

An argument that supports investing in China is the relatively low correlation of Chinese equities with respect to those of developed countries. Probably, the justification of such low correlation is the structurally different position of the Chinese economy with respect to the developed world; China still features large and positive interest rates, and the size of its central bank’s balance sheet is very contained with respect to advanced countries which have undertaken massive asset purchases programs over the past years. In this respect, Chinese equities can play a key role in reducing the risk of a global portfolio. In the following tables we show the correlations of monthly equity returns among China, Japan, UK, US, and the Euro Area over different time horizons. In general, it is noticeable that correlations among Western countries have been rising over time, especially in the past 5 years, probably due to the advent of zero or negative interest rates. However, it can be noticed that both Japan and China are lowly correlated to the Western countries.

Conclusions

Wrapping up, we think that although the Chinese bond and equity markets present a low correlation to global risk assets, the potential reward does not compensate for the numerous risks that an investor would face, especially in the short term. Lowering growth rates, increasing geopolitical risks and high regulatory uncertainty, make us believe that, with regards to the equity market, valuations should be lower to justify higher weightings in a portfolio. With regards to the bond market, we expect it to increase in size in the medium term as it is still under-developed and investor liquidity is reallocated from real estate.

Overall weight in Chinese assets should be kept low, as we expect slowing growth rates and economic damages arising from excessive regulatory control. Finally, policies enacted by the CCP to counter its structural problems might fail and geopolitical risk is very high.

0 Comments