Introduction

In the last years, there has been a slew of forced divestments in diverse industries and for different reasons. The most notorious and recent example that we have of forced divestment are the many companies that decided to divest from their Russian investments and joint ventures, because of the Russian invasion in Ukraine. Within the divestments of already impaired Russian assets and investments, the most notable one regards BP PLC and Rosneft. However, before analyzing the process of this forced divestiture and its effects on both companies’ valuations, and how it compares to other types of forced divestments, it is useful to understand the reasons behind and forms of forced divestments.

Divestment is the process of selling subsidiary investments, assets, or subsidiary units of a company, in order to maximize the value of the parent company. Although most corporations are geared up to buy assets, not sell them—the majority acquire three businesses for everyone they divest, there are many reasons that would lead a firm to divest. Often it leads to higher efficiency, as the company is able to regain sharper focus on its core business.

The divestment process is often undervalued. As a matter of fact, a study by Bain & Company found that companies who took a disciplined approach to their divestitures created twice as much value for their shareholders. In the same study, finding the right time to divest and rushing the process, were listed as two of the key factors of a successful divestiture. However, with dynamic macroeconomic and geopolitical environments, firms and funds may be forced to divest, often in short time periods, affecting ultimately the parent company’s valuation and funds return. In such cases, where the divestiture happened because of external factors be it ethical, market, or government-related reasons, we refer to these divestitures as forced divestments.

Types of forced divestments

Forced divestments have become a trillion-dollar topic in recent years. In the past, the majority of forced divestments were government-induced. With the ascension of governments that promoted planned economies, many companies had to deal with the prospect of having assets seized. Nonetheless, with a shift to a more market economy, but also the increase that ethics and sustainability play, ESG-induced forced divestments have been prevailing in an attempt of companies to maximize their stakeholder value.

Recently, the most prominent factor that led to forced divestment was ethics and compliance with ESG goals. In order to pressure the cost of capital for a firm and industry in order to push change, or simply, just not to be associated with poor carbon footprints, questionable oligarchs, or black incarceration, companies, governments, pension, endowment, and sovereign funds have been divesting from companies with poorly rated ESG practices and controversial shareholders, even if it means eventual losses.

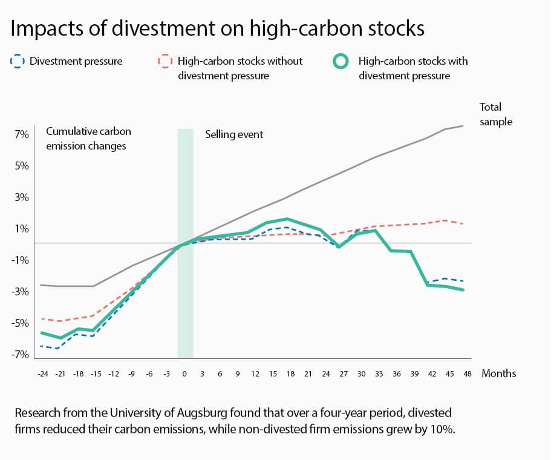

Source: https://www.corporateknights.com/responsible-investing/divestment-study

Although there is still some reluctance by some companies and funds that divesting from fossil fuels is the way to become carbon neutral, this has been the trend since shortly after the Paris Agreement. Big endowment and pension funds, and even oil-exploiting companies, such as Shell and Chevron, have pledged to divest about $39tn from fossil fuels after pressure from activist investors, quota holders, and students to adhere to the targets set. All in all, research conducted by the University of Ausburg found that the divestment pressure on high-carbon stocks has indeed affected carbon emissions. The results are depicted by the graph above, which shows after 2 years after the divestment, carbon emissions were around 3% lower, while in companies that didn’t suffer any divestment pressure it grew 10%.

Negative social impacts have also been decisive in divestments, especially regarding endowment and pension funds. What happened with Columbia University’s endowment fund—one of the ten biggest in the world—is a great example. After finding out that the fund had a stake in incarceration and private security firms, students organized consistent protests. In April 2015, the Ivy-League School’s endowment fund finally yielded and divested its stakes in G4S, the world’s largest private security firm, and Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), the largest private prison company in the United States, after claims that both companies had “horrific” human rights record.

Moreover, amidst the Russian invasion of Ukraine, many firms have announced that would be ceasing their activities in Russia in protest. Both financial investors, and companies, such as BP PLC, Glencore PC, and Shell PLC, which have strategic stakes on and joint ventures with companies like Rosneft and Gazprom, owned by oligarchs close to Putin, announced that they are going to divest from Russian investments and joint ventures. This move could represent a significant impact on their balance sheet, with billions of dollars in impairments being expected by the companies.

Nevertheless, divestments in this line have also happened before. In 2009, after the Israeli attacks in Gaza, both financial and strategic investors divested from securities that were somehow related to the attack. Even big American companies, such as Catterpillar Inc., G4S, and HP, which provided equipment and services to the Israeli government, suffered from this boycott. For instance, the Bill Gates Foundation sold its stake of over $220m in G4S.

Forced divestments could also happen due to legal and political reasons. Historically, nationalizations of industries have promoted forced divestments. Mostly seen in socialist countries, and countries with less-developed property right legislation, it may occur by expropriation and seizure of assets, in which any compensation for the assets is highly unlikely, or through forced sales. The biggest and most recent set of nationalizations happened in Venezuela, throughout Hugo Chavez’s long tenure. After nationalizing parts of many industries by legislation and forced sales, such as oil, agriculture, mining, and finance, many companies have received relatively fair compensations, whereas others still try to receive any monetary compensation through arbitration panels.

Nonetheless, forced divestments due to regulations and political reasons have also happened in countries in developed countries. As a consequence of the US-China trade war, the Committee of Foreign Investment of the US has forced Chinese investors to divest from PatientsLikeMe and Grindr, both American companies, claiming national security concerns and data theft. The Trump administration had also prohibited investments in companies linked to the Chinese military, which included Huwaei.

We will now present the BP’s divestment in Rosneft, a study of what can happen in the case of a government-induced divestment.

BP’s forced disinvestment in Rosneft.

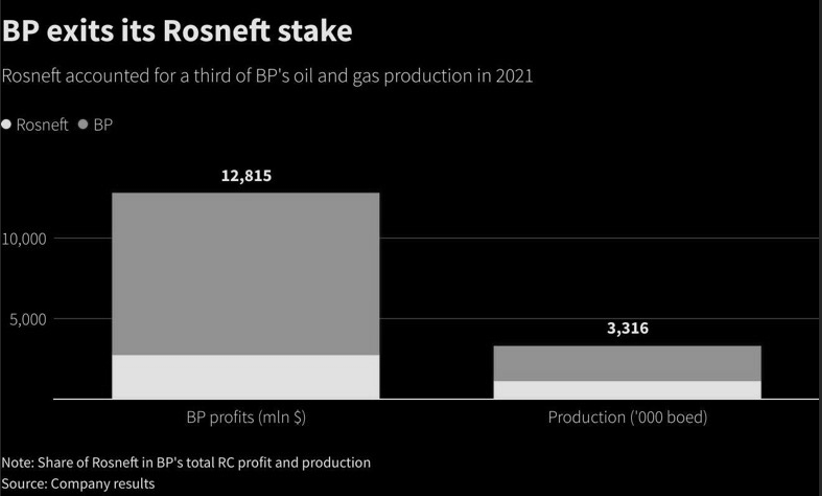

On the 27th of February 2022, British Petroleum – one of the world’s seven oil and gas “supermajors” – decidedly stated it was putting an end to its thirty years-long strategic cooperation with Rosneft, Russia’s state-owned leading oil company. Leaving no room for half-measures, BP announced it would exit its 19.75% shareholding in Rosneft, worth $14bn, terminate three other joint ventures valued at $1.4bn, and confirmed that both its CEO David Looney and former Group Chief Executive would resign from the board of Rosneft with immediate effect.

The announcement came just days after Looney was summoned by the UK’s business secretary to discuss the company’s involvement in Russia following its military attack on Ukraine. It is undoubtedly this government pressure that induced such abrupt measures. Rosneft is one of the pillars of the Russian economy: it is Russia’s biggest taxpayer – it contributes to a fifth of budget revenues – and its chairman, Igor Sechin, being a close ally of Vladimir Putin, supplies fuel to the Russian army. Interestingly, BP had previously been criticized for its stake in Rosneft, which has been under US and EU sanctions since Russia annexed Crimea in 2014.

On the one hand, the move to join the anti-Russia campaign will probably cost BP a fortune. First, the opportunity cost is high : BP has financially enormously benefited, and would have continued to, from this strategic cooperation with Rosneft. For example, in 2021, BP reported profits of $2.4bn from the shareholding and collected $640m in dividends, which represented roughly 3% of its overall cash flow from operations. Rosneft accounted for half of BP’s oil and gas reserves, and a third of its production. Analysts expected 2022 dividends to be worth well over $1bn.

Moreover, in a press statement, BP said it will “change its accounting treatment of its Rosneft shareholding”, resulting in two material non-cash charges in its first-quarter results that could amount up to $25bn. The first charge stands at $11bn, and principally arises from the foreign exchange losses accumulated since 2013 that were previously recorded directly in equity rather than in the income statement. The other charge represents the difference between the “fair value” and the “carrying value” of the stake, which last stood at $14bn. BP will no longer report reserves, production, or profit for Rosneft, and has removed dividend payments of Rosneft from its financial frame.

Fortunately for BP, its credit profile should remain intact. The expected lower dividend stream will be negative for BP’s financial profile, but this may be offset by the optimization of other cash flows and a strong market environment. Regarding the accounting reclassification of the Rosneft stake from an associate to an investment, it shouldn’t affect core credit metrics. This aspect is very important for investors when valuing companies.

Furthermore, BP said that the exit from Rosneft shareholding wouldn’t change its distribution and financial frame guidance, and it is interesting to note that BP’s stock only dropped 4% the day of the announcement, translating investors’ trust in the company.

Source: https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/britains-bp-says-exit-stake-russian-oil-giant-rosneft-2022-02-27/

On the other hand, Rosneft faces high uncertainty which has and will continue to impact its valuation. In fact, BP’s divestment is highly symbolic and has undermined Rosneft’s investors’ trust. When BP first started investing in Russia in 2003 by buying half of the oil producer TNK, it was the largest foreign investment to date and it attracted, along with the rising price of oil, global attention to Russia, sparking a wave of investments. As a symbol of foreign investments pouring into Russia after the Soviet Union’s collapse, its retreat could cause the inverse effect.

Rosneft’s future is also uncertain regarding the buyback of the BP shareholding. It could be seized or bought by private investors – expected to be Chinese in that last case. Another aspect of this uncertainty is the bilateral agreements signed by BP and Rosneft. For instance, last year, they both signed a “Strategic Collaboration Agreement” focused on supporting the carbon management and sustainability activities of both companies. The agreement built on the many years of partnership between the two companies, and formalized key elements of their collaboration on sustainability. But such agreements are today at risk as the companies drift apart. In the last two months its stock has plunged by more than ninety percent, which reflects the companies’ predicament.

0 Comments