Pre-IPO history

The legend goes that the idea for what would become a multibillion-dollar disruptive company originated when its co-founders, Garrett Camp and Travis Kalanick, could not manage to find a cab after attending a prestigious tech conference in Paris. Both already successful startup founders, they envisioned a way to book transportation directly from a smartphone.

Launched in San Francisco in May 2010, Uber [NYSE: UBER] initially positioned itself with fares around 1.5 times higher than traditional taxis, adopting a more luxurious business proposition. However, Uber’s success laid in its ability to scale across regions and diversify its services. This diversification included the introduction of Uber X in 2012, a shift towards cheaper transportation options with non-luxury vehicles, and the launch of Uber Eats in 2014, integrating food delivery into its operations. Perhaps even more impressively, Uber quickly expanded across multiple cities, setting up operations in New York City, Chicago, and internationally in Paris by 2011. In the following years, it added various European capitals and Asian cities such as Taipei and Bengaluru. Uber’s rapid expansion can be attributed to several key features of its business model. Firstly, being a technology company rather than a transportation one, Uber does not need to own vehicles or establish physical shops, making for a more scalable and asset-light company. Secondly, Uber implemented an extremely effective strategy during its early stages, which involved building loyal customer and driver bases. By launching in the heart of Silicon Valley, Uber capitalized on its disruptive appeal to tech-savvy consumers and exploited a deficient taxi service in San Francisco. It then complemented these factors with heavy investments in a referral marketing strategy, giving away free rides in order to grow customers. Leveraging this strong position, Uber then expanded into new markets, despite facing regulatory and cultural challenges.

Concurrently with its operational expansion, Uber attracted substantial investments. An initial $1.25m Angel investment led by First Round Capital in 2010 was followed by an $11m Series A funding round in early 2011, with a further $37m round later that year, which included an investment from Jeff Bezos. By 2015, a $1bn Series F round valued Uber at $51bn. As the company matured, it then pursued significant debt financing, securing $1.6bn from Goldman Sachs in 2015 and an additional $1.15bn in 2016 through a syndicated leveraged loan.

Uber’s resilience – how the company survived its numerous scandals

Uber’s considerable flow of scandals has long been an element of concern for the company’s stakeholders, and ultimately affected its already fragile financials. Under the guidance of Travis Kalanick, the company was characterized by a hostile culture that often resulted in controversies. For instance, after the publication of an article by independent journalist Sarah Lacy in 2014 – in which she accused Uber of sexism and misogyny – it was reported that one of the company’s senior executives had been recorded stating that they should have spent a million dollars to investigate into Lacy’s personal life and families, just to discredit her opinion. Subsequently, in early 2017, Uber faced allegations of misleading drivers about potential earnings, resulting in a $20m settlement with the FTC and a class-action lawsuit in NYC where the company was forced to pay drivers tens of millions of dollars in owed compensation, plus interest. The company made the news again in 2017, when a case of sexual harassment by a senior executive toward a former engineer at Uber resulted in more than 20 employees being fired and the resignation of CEO and co-founder Travis Kalanick. Uber ultimately settled claims of gender discrimination and harassment for $7m, with Kalanick also resigning from the board of directors at the end of 2019.

On top of that, there are multiple other scandals that undermined the startup’s reputation. These included Uber’s controversial ‘price-surging’ policies implemented during periods of high demand. They sparked backlash when fares skyrocketed to three to six times their normal rates during events like New Year’s Eve in 2012 and doubled following Hurricane Sandy. Additionally, a tragic incident occurred when a pedestrian was killed during the testing of Uber’s autonomous driving technology. Lastly, while not a scandal per se, Uber’s original business model has long been perceived as aggressive in its ignoring of cities and countries’ regulations, often leading to lobbying efforts to change unfavourable regulations. However, despite facing numerous lawsuits for ‘unfair competition’ from taxi companies, on top of its previous scandals, Uber consistently prevailed in US courts.

Global ambitions and preparing for the IPO

The relentless expansion that characterized Uber’s early years continued even as the company matured and eventually got closer to its IPO. As mentioned above, this was achieved through a controversial strategy that can be described as “ask for forgiveness instead of permission”. As a matter of fact, Uber’s approach involved recruiting drivers and customers in new markets through company ambassadors and promotions, while initially disregarding legal threats from governments and taxi companies to build a strong presence and garner support. Eventually, it would lobby for a change in regulations and invest heavily from the get-go to try to monopolize the market. Partly thanks to this strategy, Uber’s valuation went from $3.7bn in August 2013 to $68bn in August 2016, but cultural and legal differences across various markets meant that it achieved mixed results across different regions.

In Southeast Asia, Uber faced tough competition from Grab [NASDAQ: GRAB], a Singapore-based ride-hailing company. Although both entered the market around the same time, they adopted significantly different strategies: Grab focused on understanding and adapting to the unique characteristics of local markets, whereas Uber maintained its global approach. For example, Grab recognized that cash transactions were still predominant in many countries in the region, a payment method Uber did not accept until 2015. Additionally, it offered motorbike taxi services, which were better suited for the Southeast Asian cities’ long traffic jams. Ultimately, Uber was unable to prevail and ended up selling its Southeast Asia operation to Grab itself in 2018. In exchange, it received 27.5% of the enlarged business and a board seat. Uber would then define the operation as a financial success, considering it received a multibillion-dollar stake for a $700m investment. Similar outcomes were observed in other Asian regions. In February 2018, Uber merged its operations with Russian Yandex Taxi, securing a 38% stake in the combined entity. In China, Uber struggled to compete with regional competitor DiDi and eventually sold its operations to DiDi for an 18% stake and a $1bn investment in Uber by the Chinese firm. In fact, unique national policies and the incompatibility of Uber’s tools with Chinese platforms meant it could not fairly compete with domestic firms.

In continental Europe, Uber encountered challenges due to the less flexible regulations of civil law countries. The company faced multiple accusations of disregarding and breaking the law, resulting in fines and bans in countries like the Netherlands, Hungary, and Bulgaria. UberX-equivalent European services were also banned in various cities across France, Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands. Lastly, even in Uber’s domestic market, the US, the company had to face the competition posed by Lyft [NASDAQ: LYFT]. By the time both companies went public in 2019, Lyft had secured a nearly 40% share in the ride-share market. Lyft also symbolically beat Uber by being the first to list on a public market, as it differentiated itself with a “friendlier” image compared to Uber’s aggressive policies and continuous PR scandals.

Despite these setbacks, however, Uber continued to grow its revenues and, after a change in management in 2017, was on a mission to redefine its brand identity. As Kalanick was ousted due to investor pressure following the harassment case, Dara Khosrowshahi, then CEO of Expedia [EXPE: NASDAQ], took the helm of Uber and vowed to distance it from the hostile culture that previously characterized the company. This process also involved the listing on the NYSE through an IPO in 2019, as a way to achieve the status of a mature company and guarantee accountability to investors through quarterly reports. It also provided important liquidity for a company that was regularly reporting losses.

Uber’s IPO

Uber listed on the NYSE on May 9, 2019, with price per share of $45. The underwhelming performance of its competitor Lyft post-IPO earlier that year contributed to choosing a level near the lower end of the indicated range of $44 to $50 per share. Through the sale of 180 million shares, Uber raised $8.1bn for a total valuation of $82.2bn – with respect to fully diluted valuation, it marked the largest IPO for a US-based technology company since Facebook in 2012. However, when excluding the proceeds from the new capital raise and a $500m private stock sale to PayPal at the IPO price, Uber’s IPO valuation of $73.6bn fell short of the $76bn valuation reached during the last private fundraising round. The stock then experienced a further decline in its first trading day of 7.6% below its already conservative IPO price, resulting in a comprehensive loss of $617m for investors who purchased shares at the IPO.

Route To Profitability

Uber used to be the poster child for unprofitable tech companies. Each year it burned billions of dollars on autonomous driving, freight and food delivery. The profligacy peaked in 2019 when it made an operating loss of $8.5bn on revenue of just $14.1bn. Uber’s stock price has been on somewhat of a roller-coaster journey since its IPO in 2019, having been heavily influenced by suppressed demand during the COVID-19 and cut-throat competition in both the ride-hailing and delivery industries. Given the substantial losses, it was no surprise Uber was one of the hardest hit companies when interest rates rose. Between April 2021 and July 2022, the share price dropped by two-thirds as investors fled from loss-making technology companies. But in the past year things have changed. Despite these struggles, 2023 marked a historic milestone for Uber as the ride-hailing giant reported its first annual profit of $1.1bn for the first time since its founding in 2009. Making the transition to profitability is a crucial turning point for any technology company, signifying a fundamental transition in business dynamics, and Uber’s achievement is particularly remarkable given its historical cash burn. This section will journey through Uber’s recent post-IPO history and highlighting the key factors driving the firm’s profitability.

The wake of the COVID-19 pandemic presented fresh challenges and opportunities to Uber. As lockdown restrictions were imposed, all but necessary travel was halted which particularly damaged Uber’s traditional mobility revenue, which fell from $10.7bn in 2019 to $6.1bn in 2020. The collapse in demand further damaged Uber’s bottom line through a fall in the take-rate; the proportion of revenue that Uber does not pay out to drivers and takes itself. The take rate declined from 21% at the end of 2019 to its lowest level of 15% in the first quarter of 2021, in order to keep drivers on their app in the face of cutthroat competition from firms such as Lyft. On the other hand, as citizens were handcuffed to their homes, demand for takeaway meals grew enormously, significantly augmenting Uber’s delivery revenue, which grew from $1.4bn to $3.9bn over the same period. Uber also took the pandemic as an opportunity to overhaul its business operations, implementing radical cost-cuts, which included laying off about a quarter of its staff and the divestment of non-core businesses such as autonomous vehicles and bicycles, leading the firm to save more than $1bn in fixed expenses that year. Ultimately, the cost cutting initiative and the redirected focus on its core businesses surprisingly aided Uber in trimming its loss from $8.5bn in 2019 to $6.8bn in 2020 despite a fall in revenue from $13bn to $11.1bn during the same period.

With its focus back on its core businesses since the pandemic, Uber has shown tremendous growth across mobility, delivery and freight. Mobility revenue more than doubled post-pandemic from $6.9bn in 2021 to $14.02bn in 2022, before continuing to grow another 42% to $19.8bn in 2023. While a rebound in demand evidently played a hand in this success, a keener focus on the driver experience leading to a higher take rate of roughly 28% last year was instrumental in driving this growth. This focus has aided the 30% year on year growth in the number of Uber drivers, driving up availability and reducing surge pricing, putting off customers. Whilst Uber’s most known business segment has grown remarkably, this is not to take away from its delivery and freight business, which combined made up roughly half of Uber’s revenue in 2023. The former recorded revenues of $8.3bn, $10.9bn and $12.2bn in 2021, 2022 and 2023 respectively, whilst freight recorded revenues of $2.1bn, $6.9bn and $5.2bn. The growth of these businesses has also been significant contributors to Uber’s bottom line and its return to profitability.

Another factor that has been instrumental on Uber’s drive to profitability is indeed their chief executive officer Dara Khosrowshahi. Interestingly, two years before Dara’s appointment, he had turned down the chance to invest in the fast-growing but scandal-tainted ride-sharing startup. Dara has been viewed by Wall Street as a safe pair of hands, in contrast to his predecessor Travis, and has been responsible in helping Uber mature from the Silicon Valley disruptor to the more mature, profitable ride-hailing giant it is today. Dara has faced many challenged during his tenure, but has risen to the occasion more than once, by off-loading non-core businesses and implementing the cost-cutting strategies mentioned above. Bill Gurley, an early investor in Uber, has been quick to praise the job that Dara has done: “in terms of getting the company on the right track, putting out all those fires, getting the brand moving in the right direction again. It’s night and day.” In an effort to get drivers back to the platform after the pandemic, Khosrowshahi enhanced their riding experience and took a few rides himself to learn more about what works. Although Uber still faces an array of regulatory scrutiny, particularly in the realm of how they classify their drivers, Dara has done a fantastic job in navigating these and installing a new company culture following Travis’ dismissal. All in all, Dara has done a marvelous job in transforming Uber into the company it is today.

Current valuation

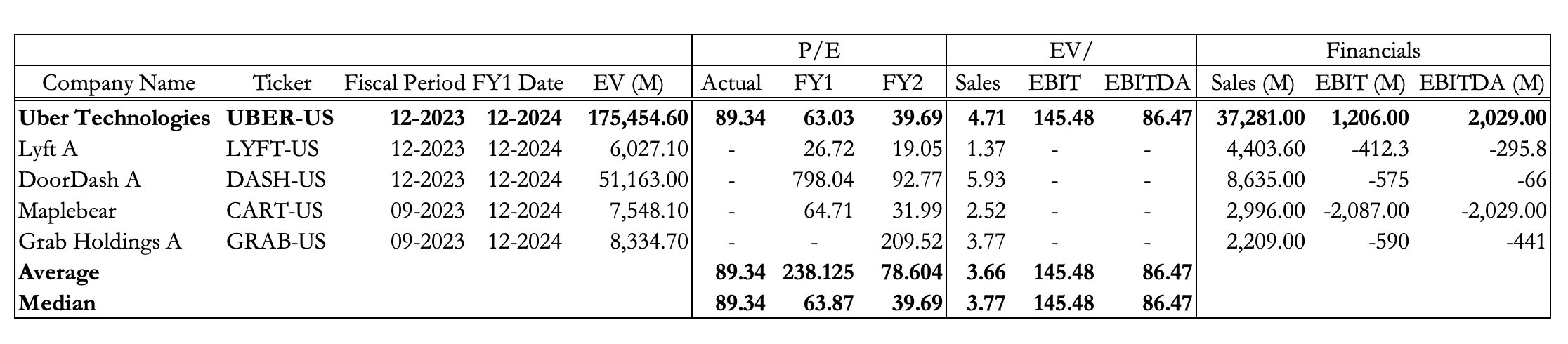

As of writing this, Uber’s stock is trading at $76 a share and is up 139% in the last year and up 36% YTD. Wall Street has never been so optimistic about Uber given its recent cash generation, which ultimately raises questions regarding its valuation and how this news will affect its competitors in this cutthroat industry. This section will take a deeper dive into Uber’s current market valuation given recent events through a comparative lens. Uber currently has a market capitalisation of $167bn with an enterprise value of $171bn and we will be looking at Lyft, DoorDash [DASH: NASDAQ], Maplebear [CART: NASDAQ] (the parent company of Instacart) and Grab.

Uber trades at a forward P/E ratio of 61, however all of its competitors listed above, have posted negative earnings and so have negative P/E ratios with this trend expected to continue. Alternatively, looking at its EV/sales, Uber trades at 4.6 times its sales. Meanwhile its competitors Lyft, DoorDash, Instacart and Grab trade at multiples of 1.4, 5.6, 2.4 and 3.8 respectively. While Uber trades at a premium to Lyft, Instacart and Grab, it seemingly trades at a 18% discount to DoorDash. This premium is likely due to DoorDash being the largest food delivery company in the United States with a market share of 56%. Their dominant position in the last mile food logistics industry is cause for much optimism amongst investors, especially given that Uber have managed to prove now that the business model can be profitable if done correctly. What investors are perhaps forgetting is that food delivery is a loss-making business, with DoorDash never having posted a positive net income in its history as a public company. Despite Uber’s delivery business draining the company’s cash, its economies of scope and profits in its other business units have allowed it to produce a profit, a luxury that DoorDash does not have.

The more cynical of investors might be skeptical of Uber’s long-term prospects and ability to stay profitable. Its current stock price of $76 implies that consensus is that Uber will be able to sustain strong revenue growth as well as margin expansion over the next few fiscal years, with a greater emphasis on the latter. Certain growth metrics such as active user growth, understandably have a natural ceiling, meaning that growth must slow at some point in time, but Uber has much scope to run in growing its revenue per user to bolster its top line. This could happen through an increase in bookings and deliveries, or even through an increase in advertising revenue on the app and perhaps during rides themselves. However, if the company can’t make this happen, then the higher multiple that investors are currently paying, is not deserved.

Figure 1: Comparable companies analysis. Source: FactSet

0 Comments