Introduction

When underwriting any debt investment, two fundamental questions must be asked: will the borrower be able to repay us? And if not, can we enforce claims over the debtor’s assets? In this article we will be discussing the increased aggression of claim enforcement- not on the company- but between creditors. Creditor-on-creditor violence refers to the tactics used by one group of creditors to improve their standing at the expense of others within the same class of debt. These strategies, which have gained traction in the United States, often involve manipulating underlying assets or creating new debt to prioritize certain creditors over others. The result is a zero-sum game where the “winners” secure more favourable recovery rates while the “losers” are left with diminished claims or devalued collateral.

The origins of creditor-on-creditor violence can be traced back to the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis. In response to the catastrophe, central banks across Western economies implemented quantitative easing and maintained ultra-low interest rates for an extended period. This environment led to the unprecedented growth of leveraged finance markets, as financial sponsors capitalized on cheap debt to acquire vast portfolios of businesses. However, this surge in leverage also led to a “covenant-lite” market, where loose credit agreements significantly weakened traditional creditor protections.

Although default rates remained low for several years, the landscape shifted as distressed companies faced difficulties refinancing their debt. As a result, some creditors started employing aggressive strategies to protect their positions, giving rise to creditor-on-creditor violence. The concept gained particular notoriety following high-profile cases like J. Crew seven years ago.

Liability Management Exercises

A significant mechanism through which creditor-on-creditor violence manifests is liability management exercises (LMEs). These are strategies employed by distressed companies to manage upcoming debt maturities, often by restructuring their existing debt. In many cases, LMEs offer creditors new debt instruments with amended terms in exchange for their existing claims, frequently at a subpar value. While these exercises can provide a lifeline to struggling companies, they often create a scenario where creditors who participate early gain an advantage over others.

LMEs have evolved to include tactics such as “drop-down” transactions, where valuable assets are removed from the collateral package, and “up-tier” transactions, where new debt tranches with superior claims are created. These strategies are designed to secure better terms for certain creditors while effectively sidelining others.

In 2017, J.Crew’s intellectual property, part of the collateral package supporting its loans, was transferred from the restricted group into an unrestricted subsidiary. This manoeuvre allowed the company to use these assets to secure new financing, which was then used to pay off another group of lenders. This left the original creditors in a significantly weaker position, prompting widespread concern among debt investors about the potential for similar tactics in other distressed situations. The J.Crew case highlighted the vulnerabilities in existing credit documentation and spurred a wave of similar transactions, particularly in the U.S. market.

Creditor-on-creditor violence has become a significant concern for financial markets and investors, especially in distressed debt. As companies grapple with financial stress, the potential for such tactics can create instability in the credit markets, leading to unpredictable outcomes for investors. This unpredictability can increase the cost of capital as investors demand higher returns to compensate for the risk of being on the losing side of such strategies. While this increased violence does provide real uncertainty for investors, LMEs give distressed companies a material way to raise capital in times of need. You might imagine that pitting your creditors against each other is a bad thing, but if you can extract value out of the fight and you are in desperate need of a lifeline, you might just resort to it.

Moreover, the rise of these tactics underscores a broader shift in the balance of power within the financial markets. Historically, creditors within the same class could expect equal treatment, particularly in restructuring scenarios. However, the emergence of LMEs challenges this notion, introducing uncertainty that can undermine investor confidence.

Key Strategies

There are two main liability management exercises that give way to the creditor-on-creditor violence that has arisen over the last few years, namely the drop-down and the up-tier transactions. Both transactions attempt to pit lenders against each other as the distressed company seeks out fresh capital from either existing lenders or new ones in exchange for seniority on existing debt.

Drop-downs

The drop-down transaction originated from J. Crew’s infamous restructuring in 2016, where new structurally senior debt was raised against already encumbered assets that were transferred to an unrestricted subsidiary. While this caught lenders off-guard at the time, in order for a drop-down to raise eyebrows nowadays it needs to be mixed-and-matched with other kinds of LMEs as part of a broader transaction such as in the Envision transaction discussed later. This is how a drop-down transaction works:

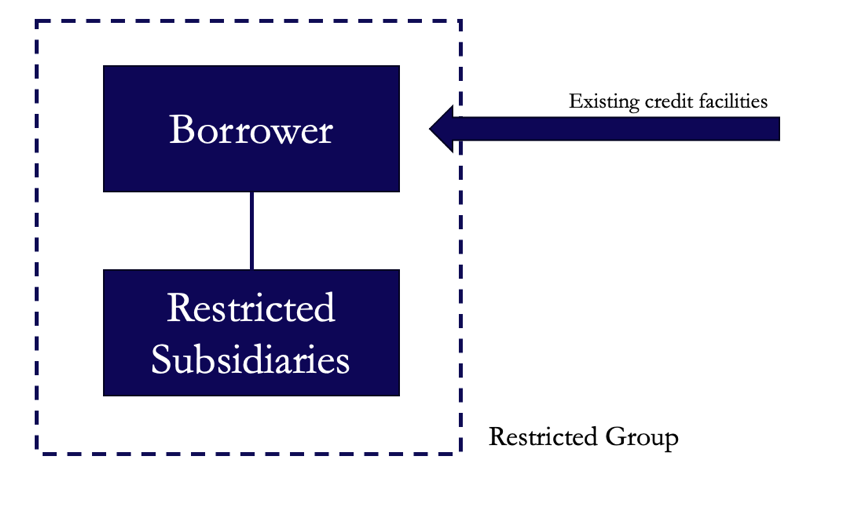

Typically a corporate structure will look like a variant of the following:

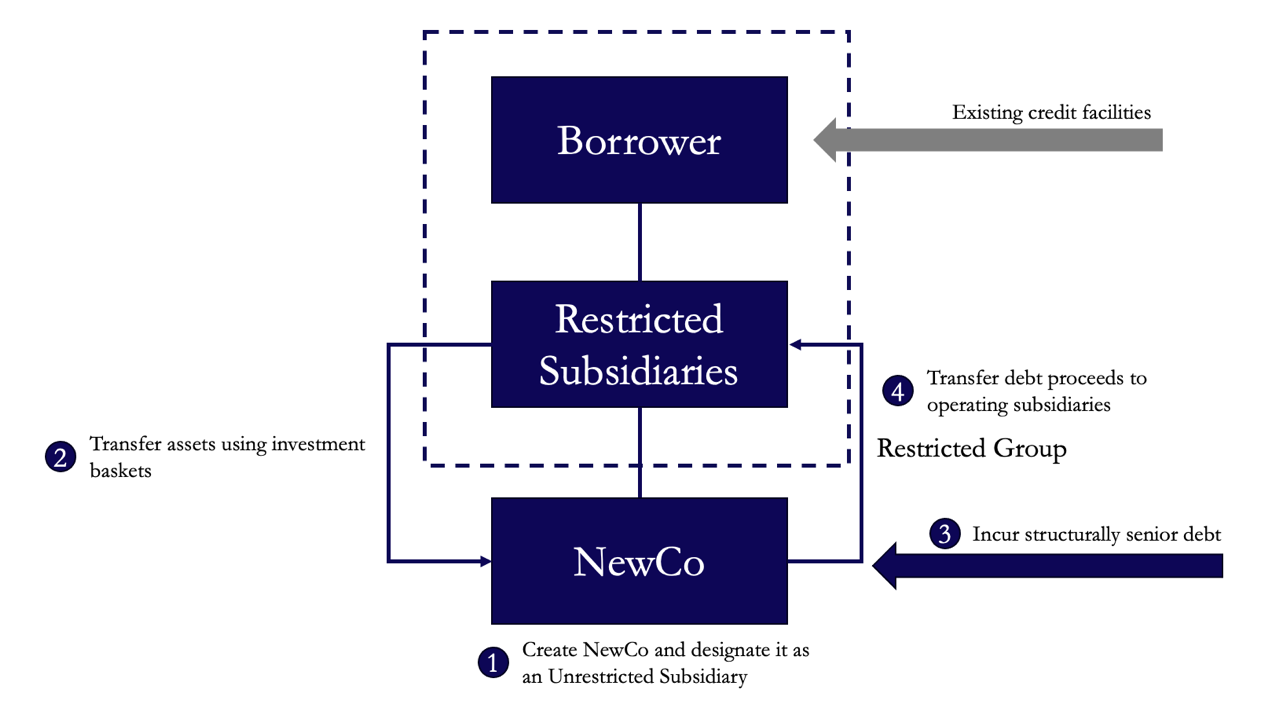

The distressed company then sets up “NewCo” and designates it as an unrestricted subsidiary. Since “NewCo” is not in the restricted group, the covenants in the existing credit agreements do not govern its activities and existing credit facilities do not have access to credit support from this subsidiary. The distressed company then seeks to transfer collateral out from under the noses of creditors, through a two-step process now known as a “trap-door” into the unrestricted subsidiary; in the case of J. Crew it was $250m of intellectual property (IP). In the case of J. Crew, the company used a $150m basket permitting investments in non-guarantor restricted subsidiaries and a $100m general investment basket to transfer the IP into a Cayman Islands restricted subsidiary (“J. Crew Cayman”). As a restricted subsidiary, J. Crew Cayman was subject to the negative covenants of the credit agreements, but as a foreign subsidiary, it was not a guarantor of the existing debt. Another investment basket allowed investments of any amount by a non-guarantor restricted subsidiary to an unrestricted subsidiary if financed with the proceeds from other permitted investments. Along with the $150m investment basket from earlier, this created a “trap door” that allowed the company to transfer all the IP into an unrestricted subsidiary (“Unrestricted J. Crew”), which was unbound by the terms of the credit documents and took away credit support from the existing facilities.

The company then began a series of negotiations with certain holders of its unsecured PIK notes to structure a series of transactions to deliver their balance sheet. The first transaction involved a private offer to exchange the company’s unsecured PIK notes for new structurally senior, secured notes issued by Unrestricted J. Crew (secured by the IP) and preferred and common equity. The second transaction involved a standard amend transaction of the term loans including a $150m cash paydown along with a bump in coupon rate and tighter covenants. As a result of these exchanges, the company was able to delever its balance sheet by approximately $340m and captured $130m of trading discount.

The essence of a drop-down is using the language in the credit documents to move assets into an unrestricted subsidiary, and raise structurally subordinated debt against them, as shown in the diagram below. It is important to note that this must all be done whilst avoiding lawsuits claiming fraudulent conveyance. In some cases, such as Altice, assets might be moved around credit boxes as a negotiating chip against existing lenders. This specific situation is a classic example of creditors calculating basket capacity incorrectly and, as a result, failing to recognise that Altice could create boundless unrestricted subsidiaries and move assets to these subsidiaries virtually at whim because of the volume of capacity that had been accrued.

Non-pro rata uptier

While there was no uptier in the J Crew case the deal laid the foundation for creative restructuring tactics that gave way to the 2 years of non-pro rata uptier ruthlessness of 2020-2022 where we saw creditors being completely left behind like in the cases of Serta and Incora (Aka. Wesco Aircraft Holdings).

Non-pro rata means non-proportionate in Latin, and that is exactly what this transaction entails, the mechanics of this will be better explained shortly, but ultimately, what happens here is that a majority of the debt holders make an agreement, in private with the underlying company, to move “up” in the corporate structure and have a bigger proportion of the debt they used to have by lending the company a new influx of capital. If you’re a participating creditor you do have to make another investment in the company. At the same time, this move gives you the steering wheel on the company’s assets, putting you in a significantly better position than the creditors you were previously pari with. In many of these cases like with Serta and Incora, or even with Envision or Apex tool the majority of the “participating creditors” (the majority lenders that are partaking in the uptier), move up the corporate structure and extract a significant amount of value from the non-participating creditors. Moving up in the corporate structure not only ensures that you are paid back first; it also means, as in the case of Incora, that only the new line of super priority credit has a lien on the company’s underlying assets. This is an important aspect, as you can kick off other creditors’ ability to seize assets in case of bankruptcy, keeping it all in the participating lender’s pockets. Beyond the clear winner in the participating creditors, the company who issues this new debt will also win because it will often be a struggling company that is in desperate need of cash, and by uptiering it can raise major cash and keep interest expenses as low as possible.

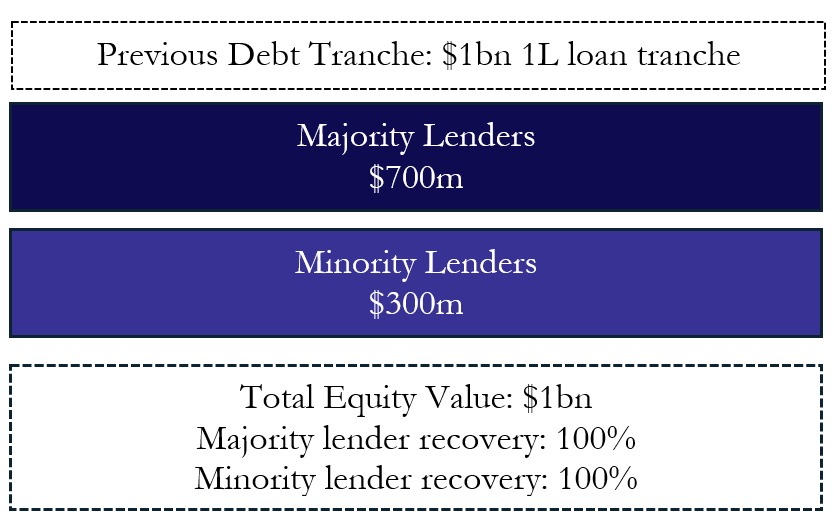

To explain the mechanics of this, we first look at a typical corporate structure which will look like some variant of the following:

In the case of bankruptcy here the distressed company would pay both senior and junior lenders back in full. But if the company were in desperate need of cash, it wouldn’t want to issue new bonds to have unfavourable terms in case it couldn’t pack it back. The company can now go to the majority of the creditors and suggest an uptier.

The actual mechanics would play out like this:

Amendments & Consent: the company will negotiate with the majority of the lenders, needing either a simple majority (50% + 1) or supermajority (66.67%) to uptier loans as per the debt contracts’ consent layouts.

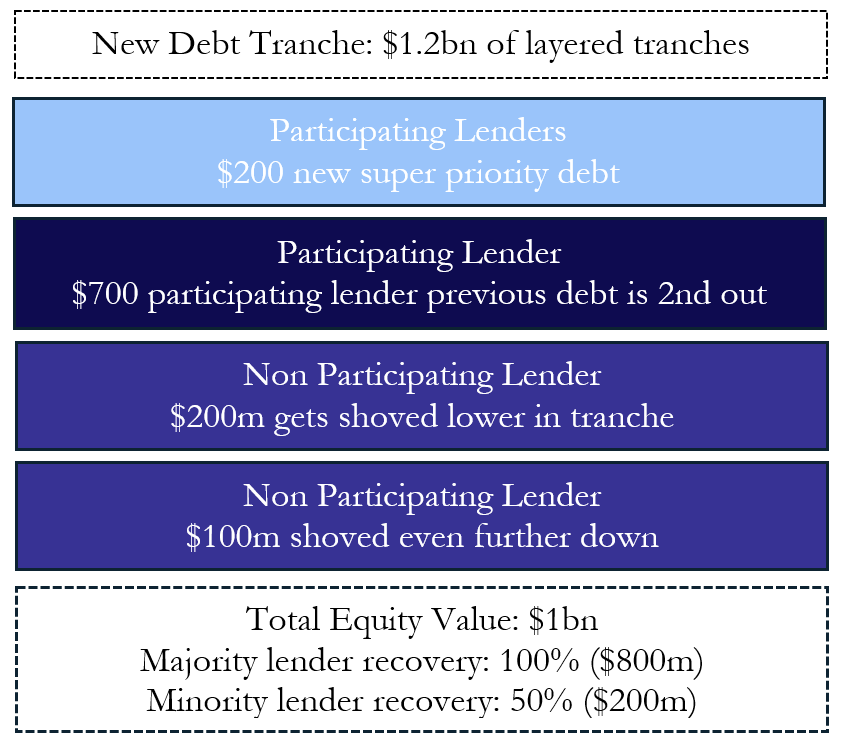

Creation of the new tranche: the participating lenders will provide new money for the company, creating a new line of super priority credit that solely has a lien on assets, meaning that any other previous debt covenant is voided and this new line of credit is senior to all other tranches. In the case of our example, this new line of credit is worth $200m.

Lien on assets and moving up the corporate structure: the newly issued super-priority debt typically has a lien on company assets, either by extending a lien over unencumbered assets or by layering over existing assets, diluting the security of non-participating creditors. In certain cases, if the company has used an unrestricted subsidiary (as seen in some drop-down transactions), those assets may be moved out of the reach of existing creditors and pledged to the super-priority lenders. In addition, the previous loan made by the participating lenders also moves up the corporate structure, meaning they are just below the super-seniority line. Since the participating lenders will have the first and second seniority bonds and 1L (1st lien) on assets, they are partially guaranteed to get their money back in case of default.

Subordination of minority lenders: the non-participating lenders are effectively subordinate; their claims represent the same nominal amount but are significantly less likely to be paid back, especially as they will often not represent the ability to seize assets in case of bankruptcy.

What makes the uptier non-pro rata is the nature of secrecy. Only the participating majority holders of these tranches have the opportunity to participate in the exchange. If they had not been given the shorter end of the stick, the minority holders would almost certainly have participated in the move. The underlying value of the company hasn’t changed; there is simply a new line of almost “phantom” credit installed, so it is likely the non-participating lenders will only get back what is left over of the original $1bn corporate structure.

The outcome is clear; the company has another $200m of capital it desperately needs and the participating lender has complete control of assets it previously didn’t.

While this is a slight oversimplification as real cases of uptiers can be slightly more complicated, the outcomes of the move are the same. In 2020-2022 the first cases of non-pro rata uptiers came out and these were truly vicious moves that ended up leaving the non-participating lenders with no value at all. Without fault, the non-participating lenders pursued legal action, and this bred a slight evolution in uptiers making them slightly more humane. In cases like Envision and Apex Tool, the majority of participating lenders will have struck a deal in private. At least in this case they offer non-participating lenders some value if they sign off with the move and agree not to sue them in return.

Case study: Envision Healthcare

Ambulatory surgery centres (ASCs) tend to be lower-margin businesses in the US due to the lower prices charged for a more affordable alternative aiming to undercut the traditional hospital market thanks to same-day procedures. In 2018, KKR [NYSE: KKR] chose to invest into Envision Healthcare for a staggering $10bn transaction value with 35% cash equity and 65% debt – leaving the company with a 7.5x Net Debt / EBITDA after the LBO. Public justifications came out for this high-leverage ratio with low maintenance CAPEX requirements, with the ASC business model as a justifiable factor.

Envision is a national hospital-based physician group that has also provided ambulatory surgery services through its subsidiary AmSurg following an all stock 2016 merger. The advantage of the transaction is that ASCs tend to be privately operated and thus are generally not owned & run by the hospital. This means they do not have to abide by the traditional rules and regulations of a broader hospital network. In addition, ASCs increase capacity to provide outpatient procedures (short surgeries lasting at most a couple of hours), covering 2/3 of the outpatient procedure market.

Envision’s approach is providing healthcare focused on emergency care – exploiting the advantage of being an out-of-network service provider to charge a higher fee. Out-of-networks are healthcare services that are not covered by insurance, and thus the difference between what the insurance is willing to pay, and the cost of the procedure is borne by the patient instead of the insurance. Through some regulatory loopholes for emergency care that enabled Envision to stay out-of-network for several insurance providers, the company was able to maintain strong pricing power and charge a significant premium to typical providers. The exploitation of the loopholes by several healthcare companies led to the threat of congressional legislation and the decision to partner with major insurance companies in the latter half of 2018 and become an in-network provider.

This was all well and good until the COVID-19 pandemic struck. Despite a temporary increase of emergency visits, the company lost nearly 70% of ex-emergency patients which tapered revenue by over $1.0bn in 2020. This was coupled with a shortage of health professionals which put upward pressure on labour costs. If it wasn’t for Donald Trump’s CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) act which provided economic stimulus to the nation and the ability to fully draw their $300m revolver, this bankruptcy would’ve happened a lot sooner. The onset of the Biden administration proved lethal for Envision as the 2020 No Surprises Act and further regulation stemming from it led to bans on balance billing (when a provider bills you for the difference between the provider’s charge and the allowed amount). This rendered Envision’s main revenue stream mute- alongside further pressure from insurance companies- increasing their denial percentages on claims and culminating in a liability management exercise coordinated by PJT [NYSE: PJT] and Kirkland & Ellis in the latter half of 2021.

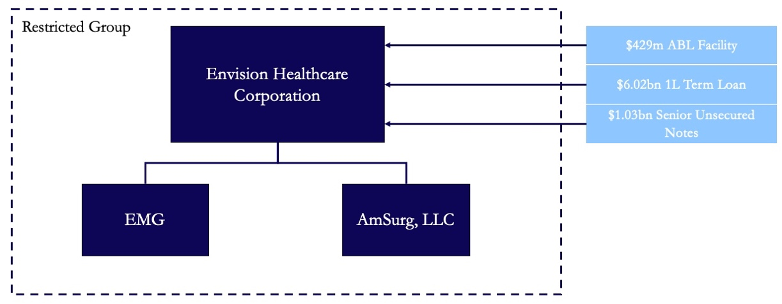

By April of the following year, liquidity problems pushed Envision to look for new financing. Their pre transaction corporate structure at the time was the following:

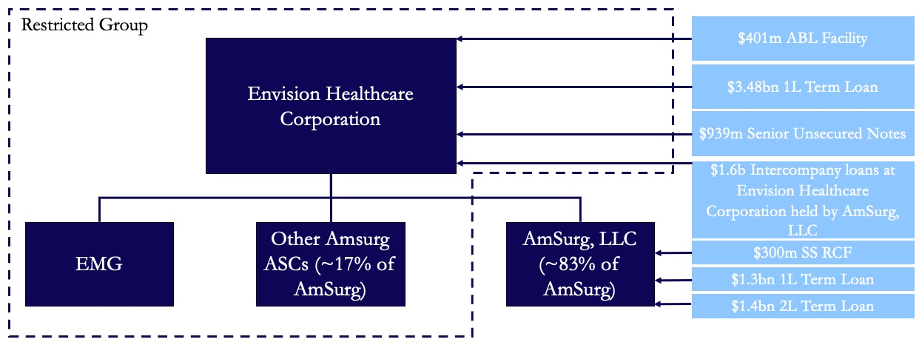

With fear of an upcoming drop-down, the bondholders rallied to prevent a situation that would demote their position in the post-bankruptcy resolutions advised by Guggenheim [NYSE: GOF] & Jones Day. In the meantime, Envision coordinated with Angelo Gordon & Centerbridge to add them to the capital structure by raising $1.3bn in new capital, leading to a hostile environment for the Guggenheim and Jones Day group of lenders. The money raised from new lenders was packaged in a longer dated 1L term loan with the ASC’s AmSurg business as collateral. Amsurg was transferred into the unrestricted subsidiary through a drop-down for 83% of its value. Envision also took advantage of loose credit docs to create a new $1.4bn 2L tranche which pre-existing lenders (PIMCO, HPS, Sculptor and King Street) decided to trade into foregoing $600m of their original $2bn stake.

To insert this new money raised from the drop-down into the system, a sum of $1.3bn was lent from AmSurg to Envision through a loan enabling them to cancel debt at discounts, fix liquidity issues, and help raise the enterprise value of the AmSurg business. Following the drop-down, Envision was essentially able to raise $2.7bn on top of the original group of Guggenheim-advised bondholders which began scrambling for a solution.

In July of 2022, a two-part uptier was announced at the Envision group level, with a $300m commitment causing the capital structure to change in the following ways:

- Longer dated 1L TL

- 2L tranche into which participating lenders would trade their debt at a discount

- Lenders in the first group at a 17% discount (Jones Day / Guggenheim)

- 2nd group traded in at a 70% discount

- 3L tranche into which the remainder of their debt would go

- 4L tranche consisting of non-participating lenders

Post uptier, Envision was able to achieve a billion dollars in discounted bonds moved up the cap structure, all while extending maturities on nearly 100% of the existing debt. Despite all the reshuffling and the three card monte that Envision tried to play, they were unable to escape the problems that plagued them. In May of 2023, they filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy with a final corporate structure:

Several proposals arose including Envision’s sale of the remaining 17% stake of the restricted subsidiary AmSurg to the new unrestricted AmSurg subsidiary (83%) in return for $300m and the wiping of the $1.4bn intercompany loan, or the sale of the remaining AmSurg stake to the public at a minimum of $0.5bn.

The following would happen to AmSurg:

- The first lien gets taken out at par through senior secured exit financing

- The second lien receives 100% of post-reorg AmSurg equity

The following would happen to Envision:

- The first lien receives a combination of cash and post-reorg debt (i.e., exit term loans)

- The second lien receives 100% of post-reorg Envision equity minus the amount given to 2L (and potentially 3L / 4L / unsecured) creditors

- The remainder receives new 3-year warrants convertible for at most 5% of new equity at a strike price that makes 1L / 2L creditors whole – with denial of the plan leading to a full wipe.

The dual restructuring plan leads to the wiping of all Envision’s c. $6bn in debt and a wipe of $1.4bn for AmSurg.

Outlook

Lenders are increasingly revisiting their contractual protections in response to the rise of creditor-on-creditor violence. Often drafted before these tactics became widespread, older contracts may lack the safeguards against such strategies, leaving lenders more vulnerable to being disadvantaged in restructuring scenarios.

To counteract this, new lending contracts are being designed with more robust protections, such as stricter covenants, enhanced collateral provisions, and explicit prohibitions against certain forms of asset transfers. These measures aim to prevent the dilution of creditor rights and ensure that all lenders within the same class are treated equitably.

Another emerging strategy to combat creditor-on-creditor violence is cooperation agreements among lenders in a syndicate. These agreements are designed to create a unified front among lenders and prevent any rogue actions by individual creditors that could undermine the group. Cooperation agreements typically prohibit individual lenders from negotiating directly with the borrower outside the group’s framework and require that a majority or supermajority of the group make decisions. This collective approach ensures that all lenders are treated fairly and that the group’s interests are protected throughout the restructuring process.

Recently, the regulatory landscape surrounding creditor-on-creditor violence has evolved as lawmakers grapple with its implications. In the United States, courts have generally treated these strategies as a matter of contractual interpretation, allowing them to persist under existing legal frameworks. However, as the practice becomes more prevalent, there is growing pressure for regulatory intervention to curb the most egregious forms of creditor-on-creditor violence.

In contrast, Europe presents a different legal environment, where courts have historically been less permissive of such strategies. For instance, English courts have refused to recognize exit consents that deprive non-participating creditors of protection, viewing them as an abuse of power. As European markets continue to develop, there is potential for further legal challenges that could limit creditors’ use of harmful mechanisms.

The sustainability of the discussed LME tactics is an ongoing debate. On the one hand, the strategy has proven effective in certain situations, allowing distressed companies to manage their liabilities and enabling aggressive creditors to secure better recoveries. However, the long-term viability of this model is questionable, mainly because the widespread use of these strategies could lead to a breakdown in trust among creditors, making it harder to negotiate consensual restructurings in the future. If lenders become too focused on outmanoeuvring one another, the collective ability to achieve favourable outcomes for all parties may be compromised, leading to more contentious and protracted restructuring processes.

Beyond the legal and financial implications, creditor-on-creditor violence raises important ethical questions. The practice inherently involves one group of creditors profiting at the expense of others, which can be seen as a violation of the principles of fairness and equity that underpin the financial markets. While these strategies may be legally permissible, they often leave a sour taste in the mouths of those who find themselves on the losing side. Additionally, when creditors engage in aggressive tactics to improve their positions, they might inadvertently push companies further into financial distress, jeopardizing jobs, suppliers, and other stakeholders. Therefore, there is an ongoing debate about whether the short-term gains achieved through creditor-on-creditor violence are worth the potential long-term damage to the broader economic ecosystem.

References

- Pari Passu, “Envision Disaster Deep Dive”, October 6, 2023TAGS: Chapter 11, Restructuring, Healthcare, Envision, KKR, Distressed Debt

0 Comments