Introduction

After two years of limited activity due to uncertainty surrounding interest rate policies, large valuation gaps, and geopolitical tensions, the leveraged finance market saw a major recovery in 2024, marking its busiest year since 2021. The combined issuance volume of leveraged loans and high-yield bonds in the U.S. and European markets more than doubled compared to 2023, driven largely by a record number of dividend recapitalizations and an exceptionally high level of refinancing activity. While M&A and leveraged buyout transactions rebounded from the low point of 2023, there is still a shortage of large deals, leading to increased competition among underwriters. Additionally, leveraged finance teams continue to face growing competition from the expanding private credit market. This article offers an in-depth analysis of the current market conditions and emerging trends.

Resurgence of Leveraged Finance Market

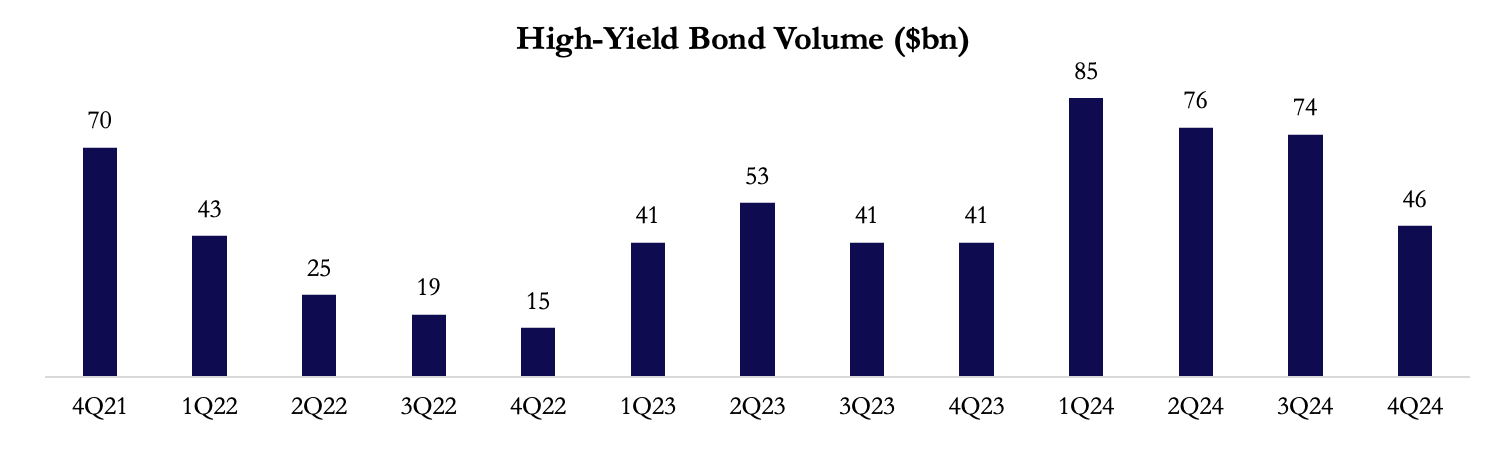

The leveraged finance market experienced a welcome rally in 2024, thanks to falling interest rates, a marginally more stabilized economic outlook and investor appetite. This rally has continued through Q1 2025, with issuer fundamentals projected to remain relatively stable, meeting or surpassing investor expectations. However, with President Trump returning to office and a melange of trade policies that have certainly incited global uncertainty, the leveraged finance market requires astute monitoring over the coming months. High-yield bond issuance in the US reached just over $281bn in 2024, more than total issuances in 2022 and 2023 combined. This increase was largely spurred on by refinancings, accounting for almost three-quarters of total issuance. Although spreads tightened by the end of the year, high-yield corporate bonds delivered an 8% total return in 2024 and there remains much reason for positivity. Sector-level disparities also declined throughout 2024, but there remained a huge gap between the top-performing sectors: healthcare, technology and transportation led the way with returns of 11.2%, 9.6% and 9.6%, respectively. For issuance volume and value, the financials, media and entertainment and high-tech sectors stood out as leaders. The high-yield market should continue to benefit from attractive supply and demand dynamics, with investors sitting on large undeployed capital. Additionally, valuations are at historically high levels and are likely to remain sustainable in a declining interest rate environment. With that being said, the current economic climate is uniquely complex. The impact of tariffs remains unpredictable and may open the door for more opportunistic activity in certain sectors. Additionally, the looming maturity wall threatening US and European markets might lead to even higher refinancing activity over the coming years.

Source: William Blair, BSIC

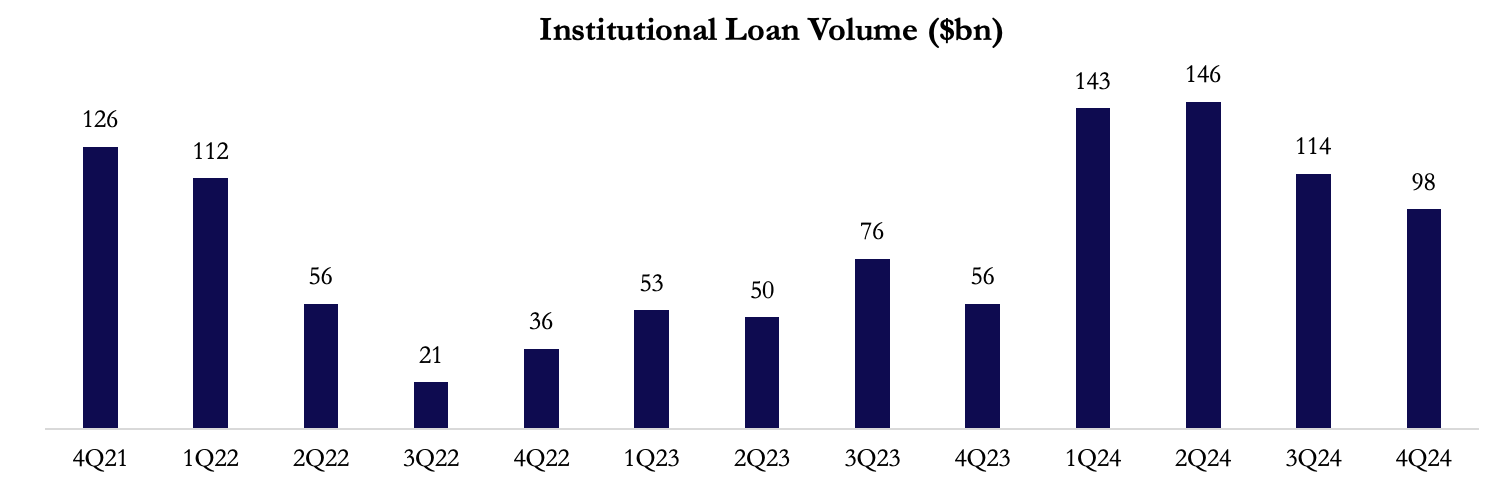

Interest rate cuts were the primary catalyst for what was a remarkable 2024 within leveraged finance markets, with overall leveraged loan activity more than doubling compared to the prior year. Most of this activity came in the form of refinancings and repricing, whilst new issuances to support M&A remained below its historical average. Global leveraged loan default rates, however, remain elevated. The bulk of issuance in this market is in the US where, in the 12 months leading up to October 2024, default rates reached 7.2% (the highest rate since the end of 2020) due to high interest rates burdening indebted businesses. Furthermore, leveraged loan spreads also experienced major compression in 2024, spurred on by robust investor demand. Leveraged loan spreads dropped 60bps in the US and 50bps for European loans since the start of 2024. This should be monitored as such steep spread compression certainly increases the likelihood of drastic repricing, should downside risks materialize, and investor appetite dwindle. This situation would place immense pressure on indebted corporates to meet near-term refinancing concerns. Dissecting the market further, term loan B activity displayed greater recovery capabilities compared to term loan A. Moreover, collateralised loan obligations, the predominant buyers of leveraged loans, saw bumper issuance as lower rates motivated investors to take more risk to secure yield.

Source: William Blair, BSIC

Fuelled by sponsors continuing to look for ways to return capital back to LPs, dividend recapitalizations experienced an immense 2024. Total volume reached $81.3bn in 2024, marking the second-highest total ever recorded. Buyout funds typically have a 10-year lifespan and currently, over half of active global funds are older than 6 years. This means that sponsors are getting pushed to exit portfolio companies and return capital to investors, which has resulted in a whole host of creative liquidity solutions. With the M&A markets remaining subdued throughout Q1 2025 and demand for returns of capital by investors, dividend recapitalizations are poised for another bumper year in 2025.

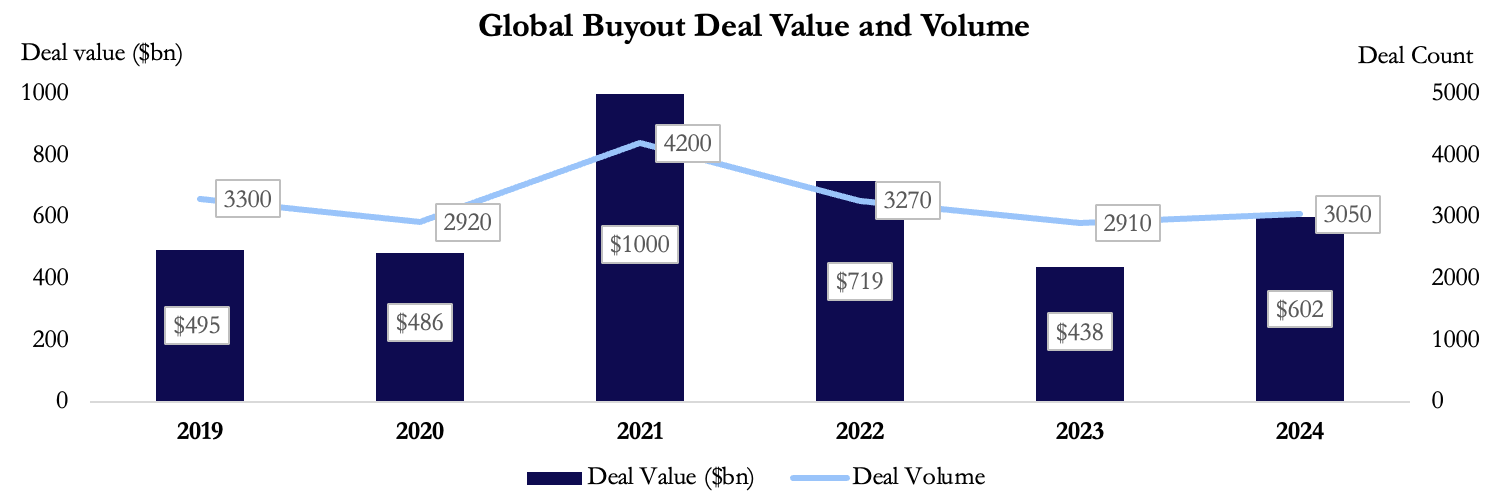

As touched upon, despite both M&A and leveraged buyout activity increasing from a dire 2023, activity remains significantly below the peak volumes of 2020 and 2021. Investors began 2025 with extreme optimism for dealmaking in 2025, however, a turbulent start has left the outlook for the rest of the year very cloudy. Falling rates and a significant build-up of dry powder provide tailwinds for LBO activity. Moreover, given the record-breaking issuances in 2024, repricing activity will probably subside throughout 2025 and the competition between broadly syndicated loans and private credit in financing LBOs will likely intensify.

Source: Bain & Company, BSIC

Banks Are Increasingly Collaborating with Private Lenders: LBO of Walgreens Boots by Sycamore

In recent years, we have seen banks and private lenders increasingly collaborating rather than competing for financing LBOs. A recent instance of this is the unprecedented buyout of Walgreens Boots – one of the USA’s prime pharmacy chains – by the famous Stefan Kaluzny-led PE fund Sycamore Partners. In many respects, this deal is unusual, both due to its nature and size. By offering to take Walgreens private, Sycamore seems to be breaking the prevailing negative sentiment towards big retail LBOs, which are seen as risky and unnecessary by other major players like KKR or Ares. For most PE funds that are comfortably diversified into credit and real estate, taking over large retail businesses is at the end of the long list of potential LBO candidates. In fact, retail is very risky and often requires lots of “dirty work”. Taking over and reshaping household names exposes the funds to bad publicity, especially when layoffs, store closures, and bankruptcies like in the cases of Toys R Us or Sears are in play. Hence, taking on a large business with retail characteristics amid growing fears of a recession seems highly unorthodox. But Sycamore is known for this: where other PEs say “no”, Sycamore thrives. Specialising in complex retail takeovers, the fund is responsible for some of the most complex retail turnarounds of the last decade.

However, Walgreens isn’t a standard retail business – it is a pharmacy chain, which makes this transaction paradoxically more surprising, even for Sycamore. Not only is it out of their standard retail expertise, as the chain has a set of its own problems not exactly like retail, but also, closing pharmacies is nothing like closing toy stores, the risk of public backlash is higher than any other fund would probably be willing to take. Hence, it may not come as a surprise that Sycamore was the only player willing to look at Wallgreens’ LBO. But the unusualness of the deal doesn’t stop here. If the risks were not enough, this deal is going to be the third-largest healthcare IPO in history and the second-largest in EU/USA region since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. Hence, it comes easy to say that the Walgreens LBO is one of the most interesting private equity deals in recent years.

While Sycamore is known for its daring and “don’t care” approach, the company has been quite successful. Thus, to understand why the fund is willing to take on this deal, let us examine Sycamore’s playbook and track record, and discuss how it will likely be applied to the Wallgreens LBO. Through the years of taking over retail businesses, Sycamore developed a tried-and-tested playbook for turning them around, and everything indicates they will use similar methods with Walgreens.

- Follow a large universe of potential candidates: The fund is known for closely following many companies in retail and other sectors, which means that whenever the company’s valuation enters an attractive range, Sycamore can buy it quickly.

- Only buy at a good price: Stefan Kaluzny is known for playing hardball during negotiations and pushing for as cheap prices as possible. Reportedly, more than once has he agreed on a given price on handshake, to then back-pedal and try to push for a lower valuation last minute before putting everything in writing.

- Realizing returns quickly: Sycamore is known for not beating around the bush and exploring all avenues to return their investment as fast as possible. This often includes complex financial engineering to get cash out quickly or, what Sycamore has often done in the past, splitting the business up and freeing up cash this way.

Sycamore has already used this palybook in the past, with varying success. For instance, after buying Staples for $6.9bn, Kaluzny was quick to separate the struggling consumer chain from the healthy B2B business and conduct a sale-leaseback on the company’s HQ to unlock more cash, generating over $1bn in dividends in just a few years. But the fund wasn’t always successful, and when they failed, they failed big, because no retailer goes down quietly. For example, the 2014 buyout of the Jones Group saw some contorvery after the sale of two of the group’s most valuable brands, just for the new business (renamed Nine West) to file for bankruptcy 4 years later in 2018.

How Kaluzny will intend to turn Walgreens around remains a question, but drawing from his well-known methods, some operational adjustments seem to be clear. While the financial engineering part remains a mystery, it has been since the new CEO Tim Wentowrth took over in 2023 that the company implemented a plan of closing 1,200 pharmacies across the US. And this seems to be a plan that Sycamore will build on. That is because the structural problems of Walgreens in the USA are significantly different to those of Boots in the UK. The US division is far less efficient, and store closures are the main tool towards addressing that inefficiency and introducing cost control. Since the problems are different for specific segments, they should be addressed locally. Hence, it is likely that we will see the company split up into smaller segments, with the UK and US divisions being operated separately to address their specific needs. Moreover, it is likely that the specialty pharma unit Shields Health Solutions will also be operated separately as it requires less restructuring than the standard pharmacy chain.

Now, it may seem as though the standard retail playbook could work here. However, one must keep in mind that the trouble of Walgreens Boots goes beyond the standard retail problems. Firstly, the pharmacy chain fell behind on agreeing better reimbursement contracts, and on top of an industry-wide downward trend of reimbursement rates, is facing even tougher conditions than CVS, for instance, which renegotiated reimbursements recently. This is a significant barrier to improving margins, and it is one that the retail-LBO masters have not faced before. This is just one example of operating issues specific to pharmacies that Sycamore will have to face. On top of that, Walgreens is facing various lawsuits regarding its handling of opioid prescriptions and perpetuating the opioid crisis, which is yet another new challenge that Sycamore hasn’t faced before. Thus, whether the retail turnaround methods will bring about better times for Walgreens remains a question.

Regardless of our views on the probability of success of the LBO, it is interesting to look at the financing of the third-largest healthcare buyout of all time. Walgreens will be taken private at an enterprise value of up to $23.7bn, including debt assumptions and potential future payouts to shareholders. The debt package will total $18.2bn, including a $4bn bridge loan likely to be refinanced in the future and $4.5bn in private loans. According to an SEC filing from March 10th most of the private credit will be provided by Sixth Street Partners, Ares, Oaktree, Pathlight Capital, and Callodine Credit Management. Furthermore, the following financing has already been committed across the three business segments: $1.25bn Preferred Equity investment from GoldenTree AM, $5bn Asset-Backed Lending Facility (ABL) committed by a Syndicate of banks, including Wells Fargo, Citi, and Goldman Sachs, $2bn First-In-Last-Out (FILO) Term Loan provided by: Sixth Street Partners, Oaktree, Pathlight Capital, and Callodine, and $1bn Receivables purchase facility provided by Wells Fargo for US Pharmacy Business. While for International Pharmacy Business, the following financing packages will be provided: $850m ABL Facility committed by a syndicate of banks, including the ones responsible for the ABL for the US segment, $2.5bn Senior Secured Term Loan, and $2.0bn Senior Secured Bridge Facility. Finally, for the buyout of Shields Health Solution a $100m Senior Secured Cash Flow Revolver Facility and a $2.5bn Senior Secured Term Loan priced at SOFR + 600bps are underwritten. On top of the segment-specific funding, Sycamore secured a $2.0bn Senior Secured Bridge Loan and $577m in credit backed by Walgreens’ real estate.

Apart from the high complexity of this deal indicated by the large portion of ABL tranches and bridge facilities, which suggests multi-phase refinancing, the cap table clearly shows a substantial share of private credit tranches – $4.5bn, which represents almost 25% of the $18.2bn package. This substantial share of private capital reflects a broader trend in LBO financing, where banks and direct lenders increasingly co-execute large and complex transactions, rather than competing over mandates. According to PitchBook’s Leveraged Commentary & Data (LCD), 17 such bank–private credit partnerships were tracked in 2024, a sharp rise from just 3 in 2023. This is due to multiple reasons. This shift is driven by several factors. Firstly, banks face regulatory and balance sheet constraints that limit their ability to underwrite and hold large volumes of risky debt, which is especially true in a higher-rate environment, which we are currently experiencing. This creates space for private lenders who are usually willing to provide riskier debt. Secondly, private credit firms have grown in scale and flexibility, enabling them to move quickly, structure bespoke deals, and hold riskier tranches like FILOs or preferred equity without the need to syndicate. Finally, for sponsors like Sycamore, this hybrid model provides greater certainty of execution and access to larger, more tailored capital stacks, which is particularly important in deals like Walgreens that cut across multiple business units and risk profiles. Thus, the combination of willingness to accept more risk, possibility to highly customise the tranches, and relatively quicker execution compared to banks, makes private credit more attractive than ever for any transactions or restrictions that involve complex financial engineering or include complicated capital structures.

Banks and Private Credit: Recent Developments

In the last decade, following the financial crisis and COVID-19 outbreak, commercial banks have faced intensified regulation, particularly in consumer lending. Private credit, or direct lending, has stepped in to fulfil the need for funding, increasingly replacing commercial banks in lending to smaller or riskier projects. The private credit sector has been able to reach $1.6tn in value and is expected to keep growing in the coming years. In recent years many banks started to break into this industry, whether this is through strategic partnerships (Citi and Wells Fargo) or by setting aside their own funding (JPMorgan). Private credit Funds, on the other hand, can get access to the whole client base of the banks and make use of the bank’s financial services to cross-serve potential clients and generate more revenues. These newly created partnerships end up benefiting both sides in different ways. For the banks, it portrays an opportunity to forego regulatory constraints as well as risk management. Through their partners, they will be able to offload the riskier items to the private credit firm and stay within the regulatory limits that restrict the banks’ ability to participate in leveraged loans. Furthermore, banks, through this new lending mechanism, will be able to generate more revenues through either the fees paid by the private credit provider or through the fees from credit given out. The private credit firms mainly aim at increasing their client base. The institutional banks can provide them with an extensive customer network to source new companies and in general, broaden the list of potential clients. Lastly, both sides aim to capture the market opportunities in this growing market and gain the largest share possible.

One of the partnerships was struck between the US bank Wells Fargo and Centerbridge back in 2023 in attempt for Wells Fargo to enter the private credit market. The partners have agreed to launch a $5bn fund with the idea of lending them primarily to midsized US companies. They set up a new business development company called Overland Advisors which primarily relies on Wells Fargo to source potential companies to lend to, while Centerbridge is using their private alternative investment capabilities to vet and analyse potential deals. The clients, while making use of Centerbridge as a partner, will primarily benefit from Wells Fargo’s full financial offerings, as they get seamless access to the company’s differentiated treasury management, investment banking services as well as senior bank capital. Behind Overland advisors are multiple investors where alongside Wells Fargo and Centerbridge also the ADIA and Canadian Pension fund invested in the first $5bn fund.

The latest deal between Citi and Apollo, amounting to a total fund of $25bn, highlights the growing trend of partnerships between commercial banks and private credit funds. This partnership’s primary aim is to lend to private equity and riskier US companies. While this deal represents a partnership, Citi is not invested in the funds but rather receives fees, through providing banking services for Apollo, mainly supporting their investment banking workforce. At the same time Apollo benefits through expanding its credit business. They want to focus on investment-grade bonds and loans and get tied up to higher-yields, but riskier investments. Apollo aims to expand its client base by leveraging Citi’s existing network. Citi, on the other hand, while generating fees, is hoping to further reinvigorate their Investment Bank, which has been struggling to keep up with its rivals in recent years. While it remains to be seen how this deal will play out for both sides, the partnership holds significant potential for growth and mutual benefit.

Another development can be seen in the example of JPMorgan Chase. The bank decided to set aside $50bn of its own money as well as $15bn from other investors to lend to risky companies backed by private equity firms in the hope of pushing into the private credit market. The endeavour started in 2021 and has been so far able to deploy $10bn. These funds have been deployed on around 20 deals ranging in size from $50m to $500m. According to Jamie Dimon, the goal of the newly formed unit is to provide clients with more options and flexibility from a bank they already know. This shift in strategy represents a complete turnaround from 2016, when JPMorgan leaders decided to sell their private credit investment arm HPS, due to a lack of appetite for further investment. But as the asset class has grown, the bank found itself again in a position to invest in private credit. To tackle the market with expertise, the new unit has partnered with seven asset managers, including Cliffwater, FS Investments, Octagon Credit Investors, Shenkman Capital Management, and Soros Fund Management.

In a similar fashion to JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs has made its mission to tackle the growing sector through their own expertise. The bank hopes to leave its mark and establish a name in the private credit sector via the newly founded Capital Solutions Group, made up of Goldman bankers that previously focused on servicing private equity and private credit clients. According to CEO David Solomon, the bank is sensing demand for private credit and private equity investing ranging from investment grade and leveraged lending to hybrid capital and asset-backed finance. Like Goldman Sachs, also Morgan Stanley is pursuing a stronger role and share in the private credit sector. The bank has instructed its asset management division to set aside a portfolio of $50bn from large investors to give loans directly to companies. The total fund is estimated to reach $50bn over the next decade and essentially assumes investments from its institutional clients. Morgan Stanley also pursues funding from outside investors and hopes to broaden their service portfolio to gain a significant share in the growing private credit market.

While not being a bank, a globally leading asset manager BlackRock also values the opportunities of the sector as by the end of 2024 they have struck a deal to acquire HPS, a dominant player in the private credit universe. The acquisition was valued at $12bn and includes BlackRock paying $9.3bn now in stock transactions and a further $2.9bn in 5 years assuming HPS can hit the financial targets. By the time of acquisition, HPS had a total of $148bn in assets under management. The acquisition offers clear benefits for both sides. BlackRock can further improve its standing in the private investment sector as they have gradually invested more and more in the field. HPS, on the other hand, can expand their business portfolio beyond junior and junk-rated bonds. Through BlackRock’s extensive network and client base, HPS will start its mission to provide capital to larger, blue-chip companies.

However, not every partnership works out and the market does prove to be competitive to break into when not partnering with the correct group. For example, partnership of Barclays and AGL credit management proved to be unsuccessful. In April 2024, AGL and Barclays agreed on a 5-year deal with a $1bn fund to help Barclays tap into the private credit market. At that point, AGL has benefited from an anchor investment from Abu Dhabi Investment Authority. However, in 2025 the companies have been struggling to further raise capital, due to a lack of prior experience and track record in the private credit sector. As the market remains highly competitive and the fundraising for private capital has fallen for the third consecutive year in 2024, it seems to benefit larger established players, while newcomers may come short.

Recent global developments and bank regulations explain why banks are searching to tap into the private credit market and enjoy the benefits of being an established player. As the funds seen by JP Morgan and Citi appear to keep growing, it needs to be observed whether these funds can improve and stay compliant with regulations. If employed correctly, this shift into the private credit sector can open a whole new revenue stream for banks. However, it remains of high importance to select the right partner on both sides as seen in the example of Barclays. As the sector reaches a more mature state with established players, it becomes difficult for newcomers to generate large shares of funding. Nevertheless, the belief remains that most banks will be able to deploy their funds and establish themselves as a viable option in the private sector market.

Large Underwriting Groups: Pros and Cons

In recent years, there has been a lack of landscape M&A and LBO transactions, leading to fierce competition between investment bankers for large mandates. However, the window is finally reopening, thus giving more work to underwriters, which are currently dealing with at least $38bn worth of high-yield bonds and leveraged loans for buyouts in dollars and euros, according to Bloomberg. The largest part of this amount is represented by highly awaited $8.04bn (€7.45bn) debt package to CD&R for their purchase of a 50% stake in Opella, consumer health unit of Sanofi. In the deal announced in October 2024, Opella was valued at 14x forward EBITDA multiple, which represents a discount of 10% in relation to such peers as Haleon and AstraZeneca. Although this discount can partly be explained by Opella’s smaller size and tighter margins, lower purchase price is also caused by the lack of strategic buyers, allowing CD&R to secure an attractive investment. At the same time, this deal will facilitate Sanofi’s refocusing on innovative medicines and vaccines, and accelerate Opella’s growth as a global consumer healthcare leader. While it is not yet clear, whether CD&R will succeed in realizing high returns and making Opella more profitable, let us not deviate from the main focus of the article and take a closer look on the financing package for this transaction.

Seven lenders, including Barclays, BNP Paribas, Citi, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, HSBC, and Societe Generale acted as global coordinators, leading the sell down of debt to institutional investors, while 22 banks in total provided financing solutions for this deal. Although recent markets volatility led the loan portion of the package to be downsized from €5.45bn to €5.2bn, overall high investors’ demand helped bankers to secure pricing of debt at the tighter end of guidance: 350bps over Euribor for the euro component and 325bps over SOFR for the US dollar tranche. The package also included €1.25bn and $1.1bn portions of fixed-rate bonds, priced at 5.5% and 6.5% respectively, in line with guidance. Moreover, banks agreed to give around €1.2bn of revolving credit facility to CD&R.

Although the underwriters committed to providing funds to the PE firm last October, they had to wait until March this year for recent financials before approaching investors, thus keeping the debt load on their balance sheets. Despite the high volatility on the markets and uncertainty around Trump’s tariffs policy, investors met the highly anticipated offer with great demand, showing appetite in the market and hopefully encouraging more deals to follow. Let us look at some specific features of this financing leading to the deal’s success.

To make the deal more attractive, the issuer offered concessions to investors on the documentation, including protective measures originally introduced by companies like J Crew, Chewy, and Serta. These so-called “blockers” make it more difficult to push through debt restructurings that would strip lenders of their claims to assets. Additionally, the borrower eliminated the high-watermark clause, which previously allowed private equity owners to base dividends or further debt issuance on the highest level of the company’s earnings, thus often overestimating potential payouts and leading to extremely high debt loads. The inclusion of the J Crew-style blockers in the Opella deal was optional, required only if investors requested them, as reported by Bloomberg.

This deal is part of a broader trend where large underwriting groups are formed for major transactions. With fewer M&A and LBO deals, banks are competing to secure mandates for any large deal, often agreeing to less favorable terms and lower fees. However, we are now seeing more collaboration among banks, who are willing to accept smaller profits in order to participate in deals, even when there are 20+ underwriters involved, as seen with Opella. The reason for this is that being one of many lenders comes with advantages, such as risk-sharing. Most notably, it helps dilute a €1.2bn revolving credit facility included in the Opella funding package. Bankers generally dislike revolvers because they require banks to set aside capital that may not be used. As a result, sharing the risk and responsibility in large underwriting groups becomes an attractive option, especially during uncertain times.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we expect continued growth in the leveraged finance market in 2025. Issuance of high-yield bonds and loans is predicted to remain strong, supported by solid fundamentals and favorable technical factors. While activity in 2024 was largely driven by refinancings and repricings, their prevalence is expected to decline in 2025 as major part of debt with upcoming maturities has already been refinanced, and M&A and LBO activity begin to recover, leading to higher levels of new origination proceeds. Additionally, collaboration between banks and private lenders is expected to persist, as the private credit market provides alternative funding solutions for companies that are unable to access public markets. However, since leveraged finance is a cyclical sector, highly sensitive to market volatility, geopolitical tensions, and broader economic dynamics, close attention will be needed to assess these factors when making predictions about the market’s performance.

0 Comments