Intro

The 2007 acquisition of Hilton by Blackstone stands as one of the most iconic private equity deals in history. Often referred to as the “best LBO ever,” the transaction blended strategic vision, operational overhaul, and a dose of good timing. Blackstone, already a powerhouse in private equity and real estate, acquired Hilton Hotels Corporation for $26 billion in a take-private deal — one of the largest leveraged buyouts ever executed at the time.

Founded in 1919, Hilton has grown into a global hospitality brand. Still, they struggled with operational inefficiencies, a high asset ownership model, and a valuation discount relative to its peers, such as Marriott. Jonathan Gray, then head of Blackstone’s real estate division, saw an opportunity to create value by shifting Hilton toward an asset-light model, improving operational performance, and capitalizing on its strong global brand.

Negotiations between Hilton and Blackstone began in 2006, and despite initial setbacks — including deal rejections and valuation disagreements — Blackstone ultimately succeeded in acquiring Hilton at $47.50 per share. Just days after the deal closed in July 2007, the global credit markets experienced a collapse. What followed tested every assumption of the deal thesis, making the eventual success all the more remarkable.

The Acquisition

Blackstone’s [NYSE: BX] acquisition of Hilton Hotels Corporation [NYSE: HLT] is a pillar of its legacy, designed by Jonothan Gray (Global Head of Real Estate for Blackstone at the time). Dawning in the summer of 2006 as Project Murphy, Gray sought to obtain “hard assets at a discount to replacement cost.”, i.e., purchase a company at a lower cost than it would be to build. He reasoned that Blackstone could extract value from the arbitrage of the market price of Real Estate Intensive Firms, such as Hotel chains, to their underlying assets. Gray, aided by contacts in UBS [SWX: UBSG], first approached Stephen Bollenbach (Hilton’s CEO) in August 2006 with the idea for a takeover. Hilton was an attractive target due to them trading at a lower EBITDA multiple compared to other competitors in the hospitality industry. Mismanagement had allowed competitors such as Marriott [NASDAQ: MAR] to catch up. Gray saw potential in the struggling firm. While Bollenbach was accepting of the concept, the two men were not able to reach a consensus over price. Blackstone and UBS both valued the firm at a share price in the high 30s, rather than the $42 share price valuation Hilton management believed. On the 25th of September, they signed a confidentiality agreement to allow Blackstone to conduct due diligence. Later, on May 15th, 2007, Gray reattempted negotiations, communicating that he would increase his bid above $40. On May 30th, he offered $42 a share but was rejected. He raised his offer to $45 a share, including special provisions such as a right to match any third-party offers and a termination fee equal to 2.75% of the equity value. This offer was swiftly rejected. On July 3rd (the offer was extended on June 24th), Gray managed to reach consensus with Bollenbach. The all-cash leveraged buy-out (LBO) was valued at roughly $26bn at a share price of $47.50. Blackstone paid a hefty 40% premium on the stock. The offer came with a $560m breakup fee in the event of Hilton backing out. The financial engineering behind the deal was paramount to its future success. Blackstone financed the purchase with $5.6bn in equity and $20.5bn in debt acquired from 26 major banks, hedge funds, and real estate debt investors. Importantly, Gray managed to secure highly competitive terms on the loans. Low rates and comfortable payment schedules allowed for more flexibility. However, the key factor that aided Gray was the removal of specific covenants pertaining to immediate repayments. Typically, when a business incurs consecutive quarters of operating losses, lenders are allowed to call back the loan. By removing this clause in the negotiations, Gray was able to better navigate the turbulent waters that lay ahead.

The Great Financial Crisis

Blackstone, however, was not off to a good start. They did not only face the challenge of creating value out of their newly acquired company, but they were soon hit with the great financial crisis (GFC), as well. Already before the deal went through, worries about rising interest rates and mortgage defaults spread across financial markets. Nevertheless, Blackstone went through with their transaction, which was led by Bear Stearns, the same bank that collapsed in March 2008, before even having issued the Commercial Mortgage-Backed Security (CMBS) for the Hilton deal. Consequently, the New York Fed bailed out the bank and took on, amid others, $4bn in Hilton debt, which JP Morgan [NYSE: JPM] did not want to take on. In addition, the heavy dependence of hotels on business cycles did not add to a successful value creations story amid the great recession caused by the GFC. This led to a 15% decline in Hilton’s revenues in 2009 and Blackstone wrote down the initial investment by 70%. Hilton’s actual EBITDA in 2009 was about half of what was projected at the time of the acquisition. While the company was not in default, the high leverage caused costs associated with less trust by customers and franchises, which would lead to decreased pre-bookings. The private equity giant smartly managed to negotiate their way out of this situation, adding to the great story of success that it turned out to become, by restructuring their debt as described in the following, but they also benefitted from good management. In April 2009 on top of the financial crisis came a lawsuit filed by Starwood, another hotel chain, owning the famous W brand, which alleged Hilton of using stolen documents for their developments. The suit was eventually settled with a fine and concession that Hilton would not hire any former Starwood personnel, which added a further financial loss to Blackstone’s investment.

Value Creation

Post-2007 acquisition, Blackstone carried out a strategy, aiming to enhance Hiltons’ operational efficiency, global expansion and conduct financial restructuring. Initially, Christopher Nassetta was appointed CEO, who quickly relocated Hilton’s headquarters to Virginia, aiming to lower overhead costs, and to create a new team, in which just 20% of original staff from Beverley Hills HQ joined.

Between 2007-2013, Hilton successful added 1,180 hotels to its portfolio, and notably rapidly expanded into the Middle East and Europe, and capitalized on the rapidly growing market in China, opening over 170 hotels there. Coupled with this global transformation, came a digital transformation. Mobile key entry and digital check-ins are just some examples of their pursuit in enhancing customer experience and their image. Nassetta also created a transformative shift in corporate culture, creating a more competitive, result-driven organisation, through using equities as an incentive to decision-makers.

Arguably the most significant contribution to Hilton’s value creation was the shift from a large real-estate portfolio, with a capital-intense model to implementing an “asset-light” strategy, putting emphasis on franchise agreements and licensing its brands to other hotel owners in exchange for fees. This approach avoided the higher capital expenditures which come with owning large real-estate assets and the sensitivity to property market, as seen in 2008. Additionally, they benefited from a far more diversified revenue structure and by 2013, ~92% of Hilton’s hotels were operating under franchise or contract agreements, contributing to their success in broadening their footprint.

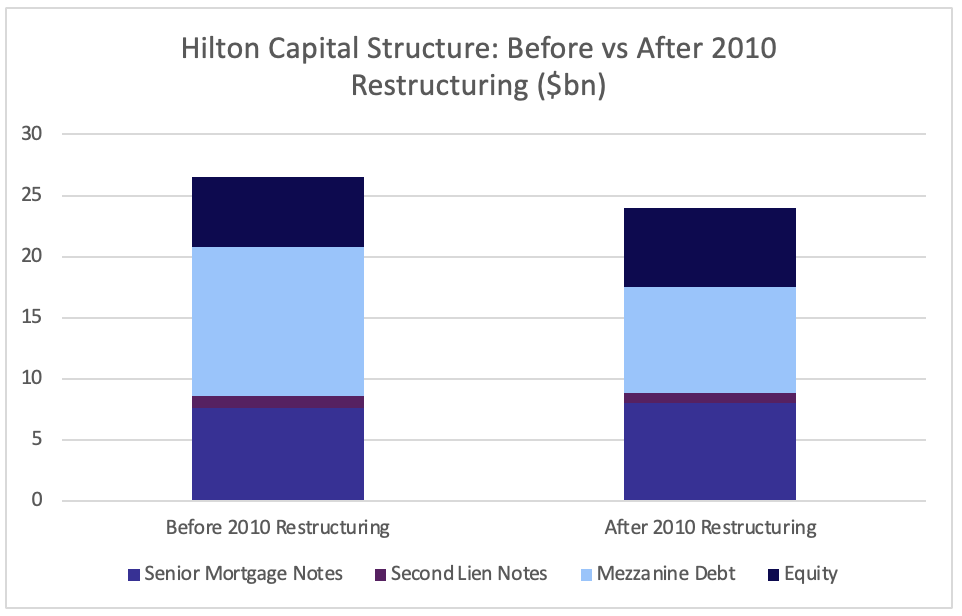

The Hilton buyout marks one of the most leveraged transactions in history, financing the $26bn deal using $20.8bn debt. The capital structure was compromised of secured debt, using senior mortgage notes totalling around $7.6bn, alongside subordinated debt, with second lien notes compromising $1bn and secured mezzanine loans I-III of $12.2bn, with higher rates. Blackstone also utilised $5.7bn worth of equity capital.

What made this LBO particularly risky was that Hilton’s high debt-to-EBITDA ratio at the time of 12.5x. When the financial crisis began, these “covenant-lite” debt avoided Hilton from defaulting, due to the debts loose financial performance requirements from lenders, meaning lenders were unable to interfere. Needing to stabilize Hilton from collapsing, Blackstone negotiated a debt restructuring deal in 2010; repurchasing $1.8bn of Mezzanine debt at a 54% discount and converting junior mezzanine loans into preferred equity, helping to remove significant debt (~$3.5bn) from Hilton’s balance sheets. Hilton also benefited from the fall in rates, saving $700m annually, allowing it to recover from the financial turmoil. One of the most critical negotiations Blackstone conducted was the extension of the maturity dates on the senior and second-lien loans, which were initially meant to mature soon after the financial crisis. Pushing back these repayments, lowered the refinancing burden for Hilton and gave them time to stabilize their organisation before having to make these payments.

Despite their substantial debt load and the unfortunate macroeconomic conditions, Hilton under Blackstone’s ownership managed to grow its EBITDA 13% between 2012-2013, driven by strategies previously discussed, positioning the company in a stable position for its IPO at the end of 2013.

Exit

After Blackstone’s success in transforming Hilton into an asset-light, global and high-growth company they took it public on the New York Stock Exchange on the 11th December, 2013. The IPO valued Hilton with an equity value of $19.7bn and with an enterprise value of $33.6bn, up from $26bn when Blackstone made an acquisition. Approximately 117.6m shares were sold at $20 per share, marking it the largest-ever hotel IPO at the time. Blackstone decided to retain a 76.2% ownership to maintain control. Throughout the next 5 years, Blackstone steadily sold its stake through a series of secondary offerings until May 2018, where they completely sold off their position. Notably in 2014, they sold 90m work of shares at $22.50 per share. In total from 2007-2018, it is estimated Blackstone generated $14bn profit from this acquisition, marking it one of the most lucrative deals see in private equity.

Back in 2014, Bloomberg labelled the deal as, “the best leveraged buyout ever” and examining what Blackstone accomplished it can be seen as a fair statement. However, it is crucial to highlight Hilton’s value wasn’t solely driven from Blackstone. A bullish market post financial crisis, slashed rates coupled with overall rising valuations in this specific sector played a large role, and this is evident by Marriott’s and comparable companies stocks experiencing large gains in the same period.

While these gains were considerable, is important to recognise, net returns for Blackstone’s LPs was significantly less, through the typical 2% management fees and a performance-based carried interest fee, estimated around 20% on profits share. Thus, the net internal rate of return to LPs after these fees are accounted for, will be considerably less than these headlines figures may convey.

Learnings

The success of the Hilton buyout underscores the multifaceted nature of value creation in private equity, which involves blending strategic management, financial engineering, and effective timing. First and foremost, the deal underscores that operational transformation is often more powerful than financial leverage alone. After the acquisition, Blackstone replaced Hilton’s leadership, relocated its headquarters, streamlined corporate structures, and instilled a performance-based culture. These interventions repositioned the company for scalable, sustainable growth, particularly through its pivot to an asset-light model, which emphasized management and franchise agreements over asset ownership.

Equally important was the structure of the LBO itself. While the transaction was highly leveraged, with debt levels exceeding 12 times EBITDA, the covenant-lite nature of the debt package proved decisive. As Hilton’s earnings collapsed during the financial crisis, the absence of maintenance covenants meant the company could avoid default and continue operating. Still, this wasn’t just a case of surviving through leniency. In 2010, Blackstone proactively negotiated with lenders to restructure billions in debt, buying back mezzanine loans at a steep discount and injecting fresh equity into the business. This capital manoeuvre significantly reduced Hilton’s interest burden, extended maturities, and stabilized the balance sheet at a time when many peers were filing for bankruptcy.

The success of the deal also illustrates the advantage of timing, or at least the ability to wait for the right moment. While Hilton struggled in the immediate aftermath of the crisis, Blackstone’s long investment horizon allowed the company to ride the eventual recovery in travel and capital markets. That said, much of the final upside came from macro conditions that were outside Blackstone’s control: falling interest rates, multiple expansion, and a booming IPO market. Quantitative decompositions of the return indicate that a significant portion of the gains could have been captured through public market exposure, particularly to industry peers such as Marriott.

Still, the Hilton deal demonstrates that private equity’s value isn’t always found in beating public benchmarks, but in ensuring that companies are positioned to survive and capitalize on recovery when it comes. And this is ultimately what set the Hilton deal apart: while other firms pulled back or collapsed under the weight of overleverage, Blackstone leaned in — not just with capital, but with a complete operational and strategic reset. Their willingness to inject equity at the bottom of the cycle, take control of the turnaround, and transition Hilton into a modern, global franchise model was the decisive factor that turned a potential disaster into one of the most profitable leveraged buyouts in history.

Conclusion

The Blackstone–Hilton buyout remains a landmark in private equity history not just because of its headline-grabbing returns, but because it exemplifies the multi-dimensional toolkit of successful dealmaking. It fused long-term strategic vision with agile crisis management, a bold financial structure with hands-on operational reform, and a readiness to invest when others retreated. While favourable macroeconomic tailwinds played a key role in the outcome, Blackstone’s proactive approach in steering Hilton through turbulent times — and transforming it into a leaner, globally scaled, asset-light powerhouse — was essential. In the end, the deal serves as a blueprint for private equity excellence, proving that true value creation lies not only in buying well, but in building better.

0 Comments