Introduction

Bulgaria –already an EU member but not yet in the euro area– has received the European Commission’s green light to adopt the euro in 2026, becoming the 21st member of the Eurozone. The ECB believes that the euro’s introduction will help improve overall economic stability and create stronger foundations for investment and for the country’s economic growth. However, populist and pro-Russian forces continue to contest this choice.

Despite political opposition and delays – Bulgaria had in fact missed the inflation criterion in 2024, thereby postponing entry by one year – the country is now meeting all the convergence criteria necessary to become a full member of the euro area.

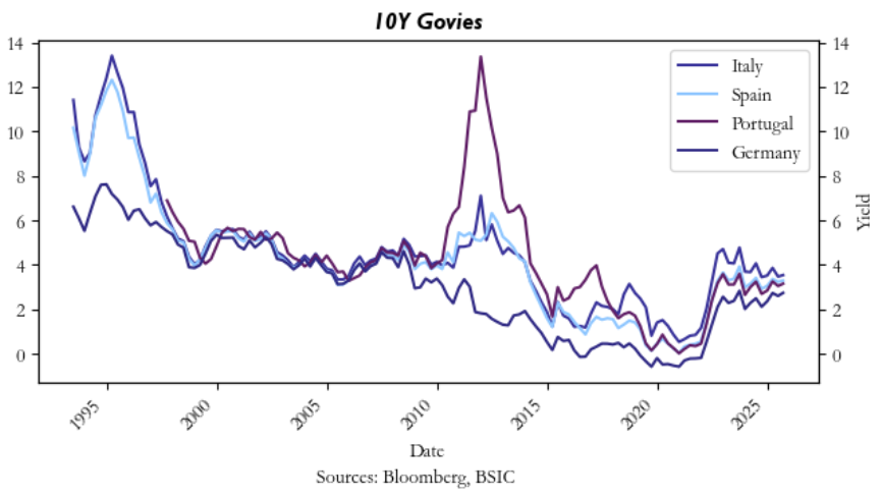

In this article, we evaluate the economic and financial consequences of this event, focusing on how Bulgarian assets may be repriced. To answer this question, we look at the experiences of those who have already followed this path. First, we compare the countries of Southern Europe that initially adopted the euro, such as Italy, France and Spain, with the Baltic countries, who adopted it later, to understand the domestic market impact of adopting the euro.

A Short History

Before comparing how the adoption of the euro impacted the debt of the different groups of countries, it is useful to recall the story of how we got there….

The first attempts to stabilize exchange rates in Europe came after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in the 1970s with the so-called “currency snake” and, about ten years later, with the European Currency Unit.

But the real breakthrough came in 1989 with the Delors Report, which proposed a path toward Economic and Monetary Union and led to the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, which established the famous convergence criteria: price stability, a deficit lower than 3% of GDP, public debt not exceeding 60% of GDP (or credibly declining), interest rates aligned with the best European countries and exchange rate stability.

Despite the turbulence of the 1992–93 currency crisis, on January 1, 1999 the euro was born as a book currency, and it entered into physical circulation in 2002.

In this context, the Southern European countries (Italy, Spain and Portugal) arrived at the appointment with the euro with fiscal situations and debt levels very different from those of the Northern countries that we will later examine. These differences would have a decisive impact on the performance of their sovereign bond markets in the following years.

As we can see in the chart, the 10-year yields of the Southern countries rapidly converged towards German levels in view of the introduction of the euro. This dynamic is consistent with the results of Erhart (2020), which shows how ex-ante convergence was a necessary condition of the Maastricht Treaty.

According to the study [2], the adoption of the euro was considered “credit positive” by the rating agencies, since membership in the monetary union improved the risk profile of the countries, compressed risk premia and reduced the probability of self-fulfilling currency crises. Due to the adoption of the euro, a country can achieve better debt sustainability, greater institutional credibility and deeper financial integration. This generated what the literature has defined as the “euro privilege”: lower financing costs, higher sovereign ratings and CDS spreads on average 10% lower compared to EU member states not belonging to the euro.

However, the experience of the Southern European economies also shows the limits of this convergence. As Bartels and Weiser (2015) argue, the creditworthiness of these countries may have been overestimated in the 2000s, with markets correcting this bias during the sovereign debt crisis. After these episodes, the so-called “euro privilege” has been gradually narrowing, and today it is far less clear-cut than in the early years.

A quick look at comparable contries…

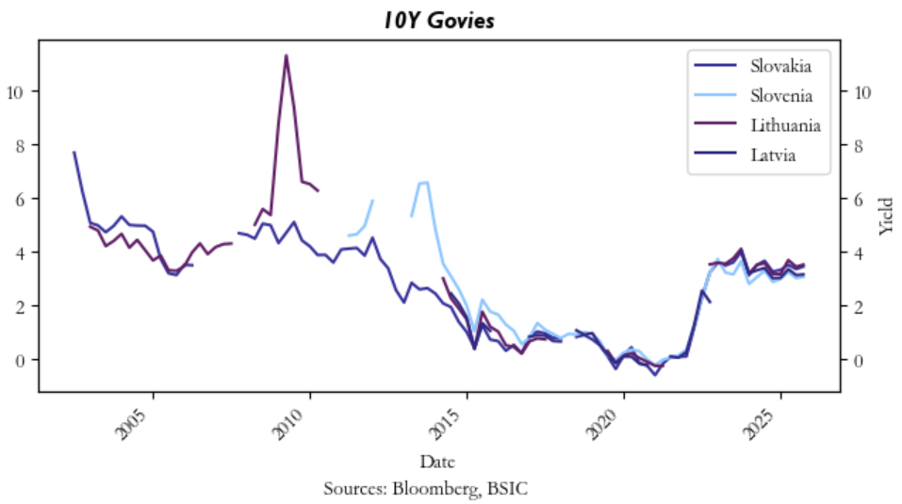

After looking at what happened to the periphery European countries, we now analyze the Baltic and Eastern European countries, which represent a very useful case of comparison to assess what might happen to Bulgaria once it joins the euro. This group includes Slovenia (2007), Slovakia (2009), Estonia (2011), Latvia (2014) and Lithuania (2015). They are relevant comparables because, like Bulgaria today, they started from relatively low levels of income and productivity, but also from very low levels of public debt, and in some cases had already introduced currency board regimes or semi-fixed exchange rates with the euro, just like Bulgaria.

The first major difference is that, unlike the Southern European countries, this group joined much later, after years of preparing their economies through rigorous fiscal discipline and comprehensive structural reforms.

The South quickly accumulated public and private debt after entry, while the Eastern countries joined with levels well below 60% and in some cases even below 30% of GDP. As a result, they were never forced into the same austerity measures experienced by Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece. Even during the global financial crisis, the Baltics accepted painful internal adjustments, (wage cuts and high unemployment) rather than devaluing their euro pegs. This resilience strengthened their credibility in the eyes of financial markets and facilitated convergence once they entered.

Boltho (2020) also underlines that the Baltics benefited from an improvement in external competitiveness and structural change. Unlike the South, where productivity stagnated and wages grew faster than output, the Eastern countries registered rapid productivity growth, a shift towards more R&D-intensive sectors and a continuous improvement in governance.

It is evident that the experience of Slovenia, Slovakia, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania shows how entering the euro with low debt, fiscal discipline and a strong commitment to reforms can generate a virtuous circle: reduction of spreads, improvement of ratings, greater investor confidence and deeper integration into financial markets.

Bulgaria

It makes sense to think about a potential convergence between the Bulgarian 10Y spread and the German one, given the dynamics we’ve discussed in the previous cases. But looking at the chart, we can agree there’s not much room left — the spread is currently at 88 bps, so we think the trade has limited gains.

This is very different from what we could have seen in Italy back in the 1990s. At that time, a “George Soros-style” trade would have been to bet on the convergence of Italy’s 10Y yields, or those of a comparable country, towards German levels. The strategy also entailed moving long on utilities which were forced to pay much higher interests than their German peers, while at the same time shorting exporters that, thanks to the weak lira, had relied on a currency advantage for their exports. Investors positioned for this re-pricing could have captured substantial returns –a much wider convergence story than what we see in Bulgaria today.

Today, in fact, it’s reasonable to think that since Bulgaria operates under a currency board, currency risk is limited, and even if funding costs were to come down, it wouldn’t spark the kind of re-pricing that could justify a “long-utilities/short-exporters” trade.

Equity Trend and Market Cap in Comparable Countries

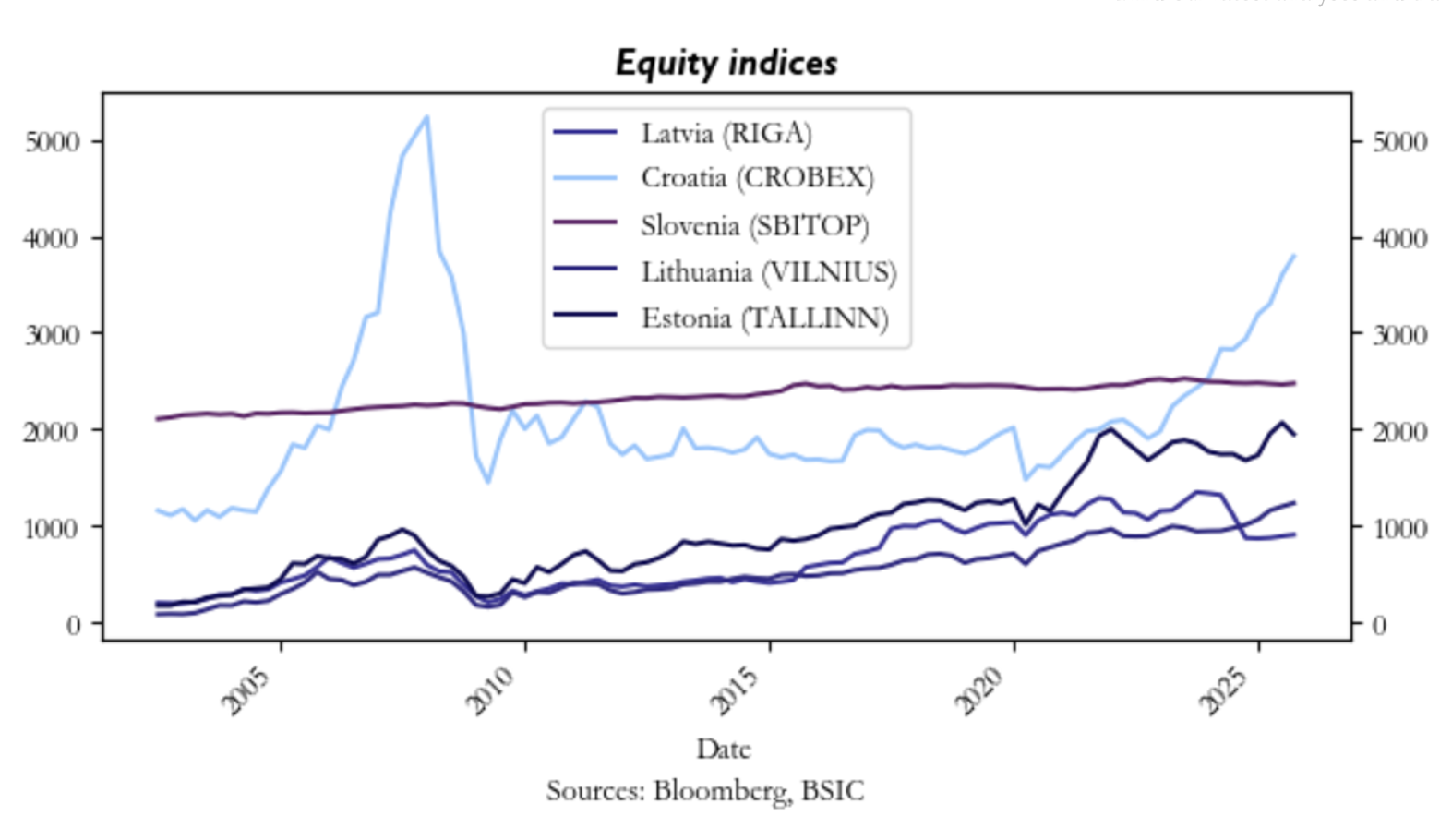

Now we ask whether the so-called “euro privilege” can also be applied to equities. With the reduction in the cost of capital and the improved perception of country risk, we examine which sectors have benefited the most in the list of comparable countries.

We begin by looking more broadly at how equity markets and market capitalisation have developed in the comparables; afterwards, we focus on the banking sector, which in study [4] emerges as the one that has undergone the most significant transformations. It is, in fact, reasonable to assume that utilities and exporters were less affected, since many of these countries operate under a currency board, where currency risk is limited.

As we can see from the chart, Estonia shows the strongest and most sustained growth after the adoption of the euro in 2011, with the OMX Tallinn index clearly outperforming the other Baltic republics. Latvia (2014) records more modest growth, but still stronger than Lithuania immediately after adoption, although in a more stable economic context. Lithuania, since 2015, has experienced a steady improvement in its equity market, with a rising performance following euro adoption.

Croatia, finally, after having had a flat equity market for years, shows signs of strengthening from 2022 onwards, with euro entry in 2023 boosting investor confidence and access to European investors.

In terms of market capitalisation from 2000 to today, Baltic equity markets have gone through sharp fluctuations but overall have shown long-term structural growth. Estonia, after adopting the euro in 2011, saw a gradual and sustained recovery in market cap, surpassing pre-crisis levels by 2021. Lithuania, which joined the euro in 2015, followed a similar though more volatile path, reaching by 2023 more than triple its 2000 values. In all cases, euro adoption strengthened investor confidence and broadened access to capital, creating more favourable conditions for local companies.

For Bulgaria, this suggests that joining the euro could represent a decisive turning point to make its still shallow equity market deeper and more liquid.

Banking sector

As we mentioned earlier, this is the sector that has undergone the most significant transformations. In the mid-1990s, banking assets in the region accounted for about 30% of GDP. By 2023, the figure had exceeded 130% of GDP. This reflects both the entry and the consolidation of foreign banks, mostly Nordic groups, which brought expertise, credibility and capital.

At the same time, integration has not been without costs. In the years leading up to the global financial crisis, large inflows of cross-border capital fuelled real estate bubbles, a rapid expansion of credit and a real appreciation of currencies. When the crisis erupted, capital flows suddenly stopped. With no possibility of devaluing their currencies without undermining credibility, the Baltics had to adjust through painful internal measures: nominal wage cuts, rising unemployment and productivity gains. GDP collapsed by between 12% and 21% across the three countries in 2008–09, while unemployment surged to 15–20% in 2010. Yet, paradoxically, this adjustment reinforced the credibility of their commitment to euro adoption and to fiscal and monetary prudence.

It is therefore important to remember that foreign capital and integration can be a double-edged sword. Before the crisis, optimism about future growth and EU accession fuelled excessive credit expansion. After the crisis, however, the willingness of foreign banks to remain in the region and the determination of governments to pursue fiscal consolidation made the recovery faster and more robust than in many Southern European countries.

Conclusion

Overall, the Baltic case shows how deep integration into European financial architecture has transformed their economies. For equities, this has meant stronger banks, healthier balance sheets, greater participation of foreign investors and easier access to capital markets. The risks – credit bubbles, sudden stops of capital or excessive political optimism – cannot be ignored, but the region has demonstrated remarkable resilience.

In conclusion, the Baltic experience can be seen as highly relevant for Bulgaria. The currency board already pegs the lev to the euro, debt is among the lowest in the EU, and the country has clear geopolitical incentives to consolidate its anchor to the West. If history is any guide, euro adoption should improve debt sustainability, attract foreign capital and lay the foundations for stronger equity and banking markets – provided that fiscal discipline is maintained and vulnerabilities in credit and real estate are carefully managed.

References

[1] Boltho, Andrea, “Southern and Eastern Europe in the Eurozone: convergence or divergence?”, 2020

[2] Erhart, Szilárd, “The Impact of Euro Adoption on Sovereign Credit Ratings and Long-term Rates”, 2020

[3] “Bulgaria to join Eurozone in 2026”, Financial Times, 2025

[4]“Should we mind the gap? An assessment of the benefits of equity markets and policy implications for Europe’s capital markets union”, ECB Occasional Paper Series, 2025

0 Comments