Introduction

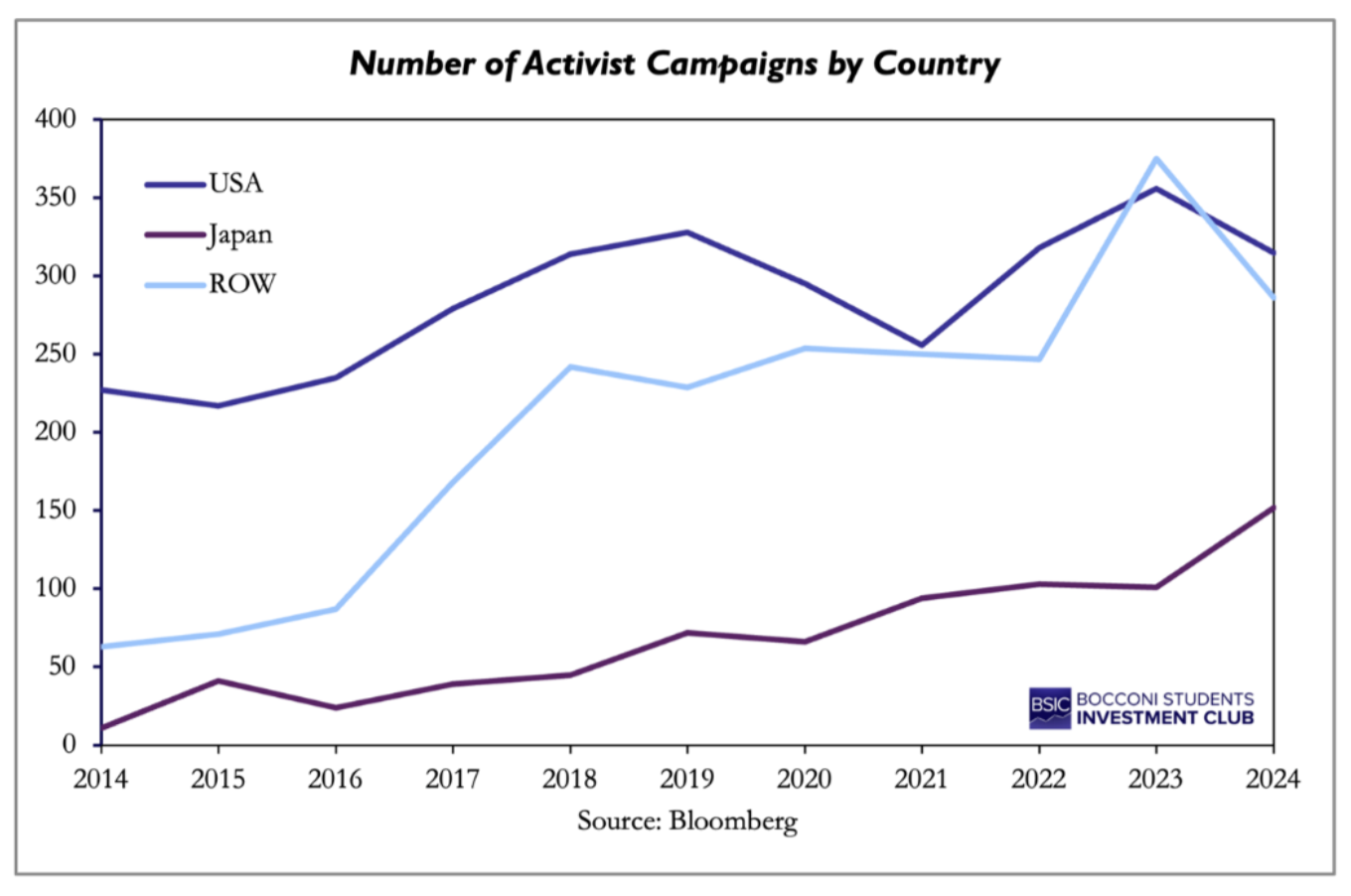

Japan’s financial and corporate landscape is entering a period of profound transformation. After decades of weak growth and institutional conservatism, the country is seeing a resurgence in the stock market, increased activist investor engagement, and growing foreign interest in private credit opportunities. Sanae Takaichi’s election as leader of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party further lifted Japan’s equity market, which had already risen about 40% in the past six months, reflecting investor optimism that she will introduce new governance reforms to strengthen corporate Japan. Moreover, alongside the booming stock market, Yoshiaki Murakami, the pioneer of Japanese investor activism, is making a comeback. This is expected to further fuel already high level of investor engagement: the country saw a record 146 activist campaigns last year, a 51% increase from 2023, making it the second most active market after the US. Furthermore, the long-anticipated rise in interest rates, together with recent corporate governance reforms, has positioned Japan as an attractive new focus for global private credit funds. All these developments indicate that Japan is entering a new phase of liberalization, corporate reform, and rising investment – a shift that will shape the future of the world’s third-largest economy and, hopefully, drive stronger growth. In this article we take a closer look at the opportunities and risks emerging from Japan’s new economic landscape, as well as examine the recent wave of activist investor campaigns in the country.

Shifting Economic Landscape: Opportunities and Risks

To begin with, after a prolonged era of zero and negative interest rates, Japan’s recent move towards higher rates has captured the attention of global private credit funds. The country’s current environment resembles that of the US after the global financial crisis, when private credit experienced rapid expansion. At the same time, Japan’s corporate governance reforms, designed to increase shareholder returns, have encouraged some company founders to consider delisting. For those unwilling to sell to private equity firms, and with domestic banks nearing their lending capacity, management buyouts are increasingly seeking alternative financing sources. This is where private credit steps in. Japan also presents a major interest because it holds one of the world’s largest and relatively untapped pools of insurance assets, second only to the US. These funds are particularly appealing to private capital managers since they offer long-term, lower-cost capital. As a result, major players like KKR, Apollo, and Blackstone are racing to build private credit operations in Japan to leverage these insurance assets for yen-denominated corporate loans. While private credit activity in the country has started to build momentum, with firms like KKR attempting to finance the founding family’s proposed buyout of Seven & i Holdings [TYO: 3382] amid a takeover battle with Canada’s Alimentation Couche-Tard [TSE: ATD], no major deals have yet been completed. Establishing the market will take time, as investors in Japan tend to be cautious with new financial innovations. Still, we think that this emerging trend holds strong potential and is for sure one to keep a close eye on.

Despite the record number of activist campaigns in Japan last year, domestic companies still struggle to deliver high returns to shareholders. Japanese stocks’ return on equity consistently lags the rest of the world, with the MSCI Japan ROE averaging around 10% throughout 2025, compared to 18% in the US and 12% in Europe. This underperformance can be explained by a lack of incentives for Japanese CEOs to achieve higher profitability. Indeed, CEO average compensation in the US and France is approximately 7x and 3x higher, respectively, than in Japan. Additionally, executive terms are short and fixed, with tenure and pay rarely tied to performance, discouraging Japanese CEOs from bold moves and risky actions. Moreover, Japan’s strict labour laws make it difficult for companies to fire employees, often prompting firms to create separate divisions to reassign workers who are no longer essential to the main business. These non-core units tend to be unprofitable, ultimately weighing down overall earnings and returns. Finally, Japan’s industries remain highly fragmented, with many small companies offering similar products, which leads to intense price competition and, thus, lower profit margins. All these factors imply that there is a lot of progress to be made by activist investors, who can force companies to divest non-core assets to increase shareholders returns. Hopefully, this will be done with the support of new corporate governance reforms expected to be introduced by Takaichi.

However, Takaichi’s prospective government will face significant challenges, most notably rising inflation and weaker yen. Known as Japan’s Iron Maiden, she is expected to champion a mix of fiscal stimulus, loose monetary policy, and structural corporate reforms, echoing the economic policies pursued by former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe between 2012 and 2020. Yet, Japan’s macroeconomic environment has changed dramatically since then. Indeed, the country is no longer battling deflation. Instead, Japan’s core inflation now slightly exceeds that of the US, with the country’s CPI excluding Fuel & Fresh Food standing at 3.3% in August 2025, compared to 3.1% in the US. However, much of this inflation was caused by an extraordinary surge in rice prices, which have doubled over the past year. When excluding both fuel and all food items, inflation falls to just 1.6%, still below the BoJ’s 2% target.

Financial markets reacted sharply to Takaichi’s victory: the Nikkei 225 rose 3.7% at the opening in Tokyo, while the yen suffered its worst drop since May as markets scaled back expectations of an interest rate hike this month from a 56% probability to just 20%. Meanwhile, the bond market has already signalled unease over Japan’s fiscal sustainability, given that the nation remains the most indebted economy among advanced countries. All above stated factors limit the scope of fiscal stimulus and lower rates, underscoring the need for a new policy approach to confront emerging challenges and sustain Japan’s recovery. However, there is one unresolved element of Abenomics – a corporate governance reform, or the so called “third arrow”, which is expected to be a central focus for Takaichi. As Japan’s first female prime minister, she could also advance efforts to boost women’s participation in the workforce, a key pillar of Abe’s earlier economic vision that has since lost momentum. Overall, Takaichi is anticipated to bring a new wave of deregulation and corporate governance reforms aimed at industrial consolidation and enhancing shareholder returns. Yet, it remains to be seen how effectively her government will navigate these newly arising economic challenges.

Evolving Climate for Investor Activism in Japan

Investor Activism – that is, using one’s stake in a company to influence its direction – was thought to be nothing more than a western trend when it arrived in Japan over a decade ago: a complete mismatch with the country’s traditionally relationship-driven and stable corporate culture. However, through regulatory change and rising shareholder engagement, it has evolved into a key force shaping Japanese corporate governance. In 2015, in an aim to address the long-standing issue of excessive cash reserves and limited accountability in Japan’s corporate sector, the Prime Minister Shinzo Abe introduced Japan’s “Corporate Governance Code” which has effectively underpinned the legitimacy of activist demands for board reform and capital efficiency. It requires listed companies to adopt a “comply or explain” policy for governance practices. By formalising expectations for board independence and disclosure, the Code gives activist investors a framework to argue for changes. If a company diverges, activists can point to violations of accepted norms rather than just their own preference. The requirement to explain deviations also helps shift debates into public justification rather than internal resistance, making them even harder to dismiss outright and boosting the influence of activist demands on firms.

More recently, in 2023, the Tokyo Stock Exchange started a campaign to highlight companies that had taken steps to raise their stock price, putting pressure on those that had not. TSE publicly ranks firms whose price-to-book ratios are below 1 and requests they submit “value-up plans”, encouraging them to adopt buybacks, raise dividends, restructure operations, or divest non-core assets. Companies that face a negative ranking risk being perceived as inefficient or antagonistic to reform and experience a decline in investment and sales as a result. In response, many firms have taken action to avoid reputational damage, like the conglomerates Hitachi [TYO: 6501] and Fujitsu [TYO: 6702], who elected to sell several subsidiaries. This institutional pressure has augmented activist influence: even firms without direct investor activism are incentivised to implement reforms, which legitimises activist demands by making them a standard practice in Japan’s corporate world.

In the same year, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Security (METI) issued its “Guidelines for Corporate Takeovers”, which state that a target company’s board must give “sincere consideration” to bona fide acquisition proposals and not automatically reject them. A prominent example of why these guidelines are critical is Alimentation Couche-Tard’s [TSE: ATD] failed attempt to buy 7-Eleven’s parent company, Seven & i Holdings [TYO: 3382]. Due to a significant lack of engagement on the part of Seven & i, the deal was officially abandoned in July 2025. While occurrences like these do put the effectiveness of such guidelines under question, they certainly underscore their necessity and further development.

One way to analyse these structural changes is via the TSE stock market index, the Nikkei 225. Since 2023, its performance has been boosted by stronger corporate profits and reform optimism, gaining over 25% through mid-2025. The rally is, in part, due to increased confidence that governance reform and investor activism will lift returns and valuations. This trend is likely to continue, as the aftermath of Sanae Takaichi election as the LDP’s new leader, and the likely next prime minister, had markets pricing a continuation of easy policy. On the day of her election, October 6, the Nikkei 225 index rose 4.8%. Investors expect the likely new PM to maintain the pro-growth and governance-reform policies, and with that, the activist-friendly environment that has persisted for the last decade.

Common Investor Practices in Japan

The necessity for such a change in sentiment becomes apparent when looking at the past. Japanese investors have long been defined by conservatism and consensus. Most domestic institutions take a relationship-based approach, often favouring long-term ties with management over confrontational engagement. The dominance of cross-shareholdings and lifetime employment culture has reinforced the focus on corporate stability. As a result, shareholder objection was rare, and investor relations were viewed as a formality rather than a forum for negotiation. While foreign investors now hold a third of the Tokyo market’s value, their strategies still encounter this culturally embedded caution. Domestic pension and insurance funds tend to vote in line with management, and retail participation remains low. Because of a preference for gradual change rather than major disruption, investors in Japan have typically pursued alignment through discreet discussions instead of applying activist pressure or have often chosen to avoid activism entirely. This consensus mindset has historically had the effect of muting the influence of short-term returns and limiting the visibility of shareholder demands in the boardroom.

That said, the boundary between traditional stewardship and investment activism is gradually blurring. Through the mentioned guidelines and campaigns, Japanese investors are beginning to adopt frameworks inspired by Anglo-American norms, focusing on return on equity, capital allocation, and governance discipline. This evolution has created a hybrid model that values stability yet no longer treats shareholder activism as taboo. Understanding these cultural norms and governance practices is key to explaining why activism in Japan remains targeted and selective, rather than the aggressive, market-moving force seen in the US or UK. Overall, number of campaigns in Japan has reached 146 last year, more than twice the number four years earlier, second only to the US and by far beating the UK.

Notable Recent Activism Campaigns

A particularly interesting player to watch during this period of transition is the New York-based Elliot Management, one of the world’s largest activist funds. After its success at Tokyo Gas [TYO: 9531] in 2024, when the firm campaigned for buybacks, and property sales helped lift the share price nearly 50%, Elliot Management turned its sights to Kansai Electric Power. Its new 4-5% stake marks one of the first activist forays into Japan’s nuclear sector, long viewed as off-limits. Elliott is pressing Kansai Electric to sell ¥150bn in non-core assets each year to use the proceeds for dividends and buybacks. That follows the pattern activists are now using across industries: forcing companies to divest non-core assets to increase shareholders returns.

Farallon Capital, another US fund, has taken a similar approach to T&D Holdings [TYO: 8795] a major Japanese insurer. Its push for faster restructuring and new outside directors in Japan’s tightly regulated insurance sector shows how activism has expanded into market sectors that previously were quite isolated. Farallon’s campaign, focused on trimming equity risk and reducing cross-shareholdings, fits neatly into the new regulatory and governance agendas. Notably, this trend is not isolated to big players, smaller and newer entrants are following suit. London-based Palliser Capital recently disclosed a 3% stake in the Japanese tiremaker Toyo Tire [TYO: 5105], pressing for a leaner balance sheet and a review that could include a sale. In fact, even Mitsubishi Corporation’s [TYO: 8058] stake of 20% in Toyo Tire is coming under debate, as some believe it to be contributing to an unfairly conservative financial approach. The fact that the stake of a firm like Mitsubishi has come into question shows just how deeply this new activist agenda has penetrated Japan’s corporate world.

The important thing to note is that investor activism in Japan is here to stay, its reach is expanding, and so will its impacts. The Tokyo Stock Exchange’s reform campaign and METI’s governance rules have lowered barriers to enter for activist investors. Funds no longer need to position themselves as outsiders forcing their will, they can present their proposals as helping Japan meet its own reform goals. The country’s final frontiers for activist investors, like nuclear power and insurance, are no longer closed. With a new leader advocating for shareholder influence and a growing cultural shift, the real question is not if investor activism will continue, but how profoundly it will transform Japan’s capital markets and corporate culture.

Yoshiaki Murakami – Pioneer of Japanese Investor Activism

Yoshiaki Murakami, widely known as the grandfather of Japanese investor activism, played a pivotal role in transforming Japan’s corporate governance landscape. Born in Osaka and educated at the University of Tokyo, he left the Ministry of International Trade and Industry to establish the Murakami Fund, seeking to confront Japan’s long-standing corporate stagnation. By investing in underperforming firms and advocating for more efficient capital allocation, Murakami introduced a shareholder-oriented perspective that was revolutionary in a market traditionally resistant to investor intervention. His idea that “money is to a company what blood is to the human body” reflected his view that capital needs to keep flowing for a business to stay healthy and expand. Although later convicted of insider trading and sentenced to two years in prison (his sentence ultimately suspended on appeal), Murakami remains widely respected as a visionary reformer who foresaw the rise of active ownership and modern corporate responsibility in Japan.

In 2000, right after starting his fund, Murakami tried to take over Shoei Co. [TYO: 7839], a real estate and electronics company. This is often called Japan’s first hostile takeover attempt at domestic level and marked a turning point in the country’s corporate governance history. Through his fund, Murakami offered ¥1,000 per share for Shoei and eventually increased his stake to 6.5%. Although this was not enough to gain corporate control, the campaign exposed deep structural inefficiencies in the Japanese corporate system. Shoei was part of the Fuyo Group [TYO: 8424], a keiretsu network (system of interlinked companies) in which banks, insurance companies, and industrial firms hold cross-shareholdings to protect themselves from outside influences. These alliances restricted market discipline by shielding companies from shareholder pressure and competition for capital. Murakami uncovered hidden value of around ¥70bn (approximately $650m) in Shoei’s real estate portfolio, revealing how assets were chronically undervalued and underutilized. By publicly challenging this system, he introduced the concept of shareholder value into Japanese corporate discourse and demonstrated that even an unsuccessful takeover can bring about long-term institutional change.

Murakami’s activist fund strategy was extremely successful in its early years: By 2006, the Fund had grown from ¥3.8bn to around ¥444bn, an increase of over 100x, by acquiring shares in cash-rich companies and pressuring them to increase dividends, conduct share buybacks, and pursue strategic mergers. In 2006, however, he was arrested for insider trading in connection with Livedoor’s attempted takeover of Nippon Broadcasting System [TYO: 9414], a major radio broadcaster with control over Fuji Television. Prosecutors accused Murakami of buying ¥10bn worth of NBS shares before the transaction was made public, thereby making a profit of ¥3bn. He was sentenced to two years in prison, but the sentence was suspended on appeal. His fund was subsequently dissolved, yet Murakami reemerged around 2015 and has since participated in at least 80 activist campaigns, reestablishing himself as one of Japan’s most influential advocates for corporate transparency and shareholder value.

In 2021, Murakami made headlines again by outmanoeuvring global private equity giant Carlyle Group [NASDAQ: CG] in the high-profile takeover battle for Japan Asia Group [TYO: 3751], a renewable energy and infrastructure company. Carlyle, together with JAG’s CEO, had launched a management buyout (MBO) at ¥600 per share, later revising it to ¥1,200 per share plus a ¥15bn cash payment for subsidiaries, valuing the firm at roughly ¥48bn. The plan effectively carved out JAG’s most profitable energy and infrastructure units for Carlyle, while allowing the CEO to retain control of the rest for just ¥2.5bn, a structure that gave management private gains by agreeing to sell the subsidiaries below their true market value. City Index Eleventh, Murakami’s investment arm, had already built a 20.5% stake and countered with a ¥1,210 per-share all-cash offer, which provided higher immediate returns for shareholders and ensured that all investors shared equally the company’s full asset value. Carlyle ultimately withdrew its bid after failing to attract sufficient shareholder support. When JAG’s management announced a special dividend of ¥300 per share, the timing was widely interpreted as a poison pill, a defensive measure aimed at draining cash reserves and complicating Murakami’s acquisition. Murakami responded by withdrawing his initial tender and relaunching it at ¥910 per share, preserving the same effective payout for shareholders after adjusting for the dividend. This move neutralized the management’s defence and maintained valuation consistency. City Index ultimately gained control of JAG and, one month later, sold the company’s subsidiaries back to Carlyle, realizing an estimated ¥36bn profit, the value that, under the original MBO structure, would have been captured privately by management and Carlyle. The deal cemented Murakami’s reputation as Japan’s most sophisticated activist investor, proving that disciplined valuation and equal treatment of shareholders can yield both strong financial returns and lasting governance impact.

In 2022, Murakami turned his attention to JAFCO Group Co. [TYO: 8595], Japan’s largest publicly listed venture capital firm, launching one of his most debated activist campaigns since his return to the market. After quietly building a 19.5% stake, Murakami pressed JAFCO to sell its 3.9% holding in Nomura Research Institute [TYO: 4307], worth about ¥80bn, and to use the proceeds for a major share buyback, arguing that the company’s stock traded roughly 40% below its net asset value due to excess holdings and weak capital allocation. Concerned by his growing influence, JAFCO’s board considered adopting a poison pill defence, involving the potential issuance of new stock warrants to dilute Murakami’s stake if he pursued his stated plan to increase ownership to 51%. Despite the warning, Murakami continued accumulating shares, forcing negotiations. The standoff ended when JAFCO agreed to sell its NRI stake and launch a ¥42bn tender offer, about one quarter of its market capitalization, to repurchase Murakami’s shares at a premium price, effectively allowing him to exit with an estimated ¥7bn profit. Analysts and governance experts labelled the outcome a classic case of greenmail, in which a company buys out an activist’s position above market value to neutralize a perceived takeover threat. While the market criticized JAFCO’s capitulation as a governance setback, the episode underscored Murakami’s enduring ability to identify undervalued corporate structures and turn strategic pressure into both financial and structural impact.

Nearly two decades after his first clash with Fuji Media Holdings [TYO: 4676], Murakami has once again turned his attention to the same corporate empire. In September 2025, he and his affiliated entities disclosed a combined 16% stake in the broadcaster, signalling a renewed campaign to pressure the company to restructure its sprawling portfolio and unlock shareholder value. Entities linked to Murakami have even floated plans to raise their holdings to 33.3% and urged Fuji Media to spin off key subsidiaries, including one that Murakami’s group could potentially take control of. Fuji Media, still recovering from a reputational crisis following a sexual-assault scandal that cost it sponsors and viewers, rejected the proposals and cautioned that Murakami’s group “may act to maximize its own interests rather than those of all shareholders.” In response, the company’s board began considering a poison pill-style defence, allowing it to issue new shares if any investor exceeds 20% ownership. Murakami’s renewed battle with Fuji Media is a symbolic test of how far Japanese corporate governance has evolved since his first campaign in the early 2000s. Whether this confrontation will end in another profitable settlement or a decisive showdown over the limits of shareholder activism remains to be seen. One thing is certain, however: Murakami’s presence continues to force the Japanese corporate world to ask itself whether long-term stability should outweigh accountability and market discipline.

0 Comments