Origins and Historical Growth

Beginning in the 1980s, Asian private equity (PE) was still in its infancy. It was supported only by a few hundred million dollars in AUM and had a heavy reliance on public funding. Private limited partners (LPs) were rare, and capital originated mostly from development finance institutions (DFIs), which were quasi-government agencies tasked with assisting private sector projects to promote economic development. Throughout the 1990s, activity continued to be modest as investments focused on minority-growth or VC. Overall, the Asian economy was dominated by large family-owned conglomerates or, for example in the Chinese situation, state owned enterprises. This offered limited buyout opportunities for general partners (GPs). The poor conditions were amplified by the 1992 collapse of the Arral Pacific Fund due to a GP dispute. This left $176m on the table, sparking (wrong) speculation about the imminent collapse of the undeveloped Asian PE market.

The turnaround started in the early 1990s where AUM in Asia surged from about $30bn in 1994 to ~$80bn by the late 1990s. The growth was further amplified by the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997-1998. Conglomerates collapsed, currencies devalued (some by more than 50%), opening the door for foreign investors to acquire larger, meaningful stakes in incumbent companies. Most notably, South Korea, an economy previously defined almost exclusively by venture capital, saw 22 buyout and restructuring transactions from 1998 to 2001, totalling more than $4.1bn. The crisis marked a shift in focus from expansion capital towards turnaround buyouts in many Asian countries, laying the groundwork for the development of a flourishing PE environment.

The early 2000s were characterized by a rapid expansion of the industry, with PE investment growing around 22% annually (Greater China even at 47% and India at 59%). Post-Crisis recovery, robust GDP growth, and the emergence of China as a global economy through trade liberalization, privatization, and membership in the WTO awoke the potential of Asian PE. Companies like KKR [NYSE: KKR], Warburg Pincus, Newbridge Capital [NASDAQ: TPG], or Ripplewood Holdings established Asian operations, committing to landmark transactions such as the take-over of Korea First Bank or the acquisition of a controlling stake in Shenzhen Development Bank for $1.4bn. China led Asia’s PE growth, but India and Southeast Asia rose as markets for growth equity. Buyout activity however remained modest relative to growth capital. Overall, the increasing deal count contributed to the erosion of the region’s resistance to foreign capital, opening the door for future growth, but challenges such as corporate governance and social hurdles kept buyout levels below the West. Minority stakes were the norm with large leveraged takeovers only being seen in Japan, Korea, or Australia.

Similar to the Asian Financial Crisis, its global counterpart in 2008-2009 marked another inflection point for the industry. The lack of Western fundraising and investment froze Asian PE markets. Deals were put on hold or called off; IPOs were delayed. Nevertheless, motivated by strong domestic stimulus Asian GDP growth, especially China’s and India’s (around 10% in 2010), rebounded faster than that of the U.S. or Europe (around 2% GDP growth), accelerating the rise of the PE market.

In the 2010s, due to the global economic uncertainty, investors increasingly turned to Asia as a growth engine. In consequence, the market matured significantly with many GPs raising third, fourth, fifth funds during the period. Also exit channels improved as Hong Kong and Shanghai developed flourishing IPO markets for PE-back companies, and secondaries became more popular. By the end of the decade, the internet and tech sector had become the largest component of Asian PE by value (roughly half of exit value in peak years). The growth was fuelled by rapid urbanization, an increasingly wealthy middle class, and a technological revolution giving rise to massive tech unicorns like Alibaba [NYSE: BABA] or Tencent [HKG: 0700]. Simultaneously, Asian PE poured money into the industry and large funds with $5-10bn in AUM created unprecedented capital availability. Asia-Pacific private equity had firmly become a core pillar of global private markets.

However, in 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic once again halted the momentum. Severe travel restrictions, business closures, and a general economic slowdown resulted in high uncertainty and volatile markets, causing deal activity to pause sharply. A “capital hold-up effect” set in, as portfolio companies stayed private for longer, freezing capital and preventing redeployment. Though the market rebounded quickly in late 2020 and 2021, where there was record PE exit value in Asia (mostly contributed by an increase in IPOs and secondaries) by 2022 new headwinds emerged. The war in Ukraine and rising interest rates around the world slowed deal activity again, plunging 33% year-on-year to $132bn. Furthermore, fundraising also fell as Asia-focused funds only comprised around 10% of global PE capital raised in 2022 (16% in 2021).

Backdrop For Private Equity Investments in Asia

Diving into the backdrop of the Asia-Pacific investment landscape, the region navigates 2025 with a redefined growth narrative amid fewer minority transactions but larger deal sizes, greater operational involvement, and expanding sectoral themes. The current deal environment consists of three main opportunity zones: corporate carve-outs, take-private transactions, and digital asset infrastructure. This transition provides an interesting signal of the Asian private equity landscape, as investors across the board have agreed that we are seeing a secular rotation from minority allocations in growth sectors into larger-scale control plays that can benefit from direct operational improvements and sponsor-led value creation. This trend is highlighted by the growing value of deal activity in the region, which reached $176Bn in 2024 and posted an 11% YoY growth rate, as the region takes an increasing share of private equity firms’ portfolios. In contrast, deal count declined 9% to 1,292, underscoring a decisive shift away from minority investments and towards majority control across allocations.

Looking at the macro, we can define Asia’s backdrop as being one of asynchronous growth, evolving policy regimes, and fiscal tailwinds in some of its players, such as the case of Japan, which creates an environment that is crucial for investors to understand to allocate capital in a region that is growing dissimilar. In terms of the Asian GDP growth story, it remains highly positive in economies such as India and Southeast Asia, which are growing at 6.7% and 5.3%, respectively. In Japan, it is expected to grow by 1.2%, a notable uptick from prior years of economic stagnation. However, on the other hand, with China we face a different environment as growth is slowing down at an expected rate of 4.4% for 2025, which despite being high by global standards showcases the possibility of a secular slowdown fueled by regulatory uncertainty, geopolitical tensions as a result of the US/China Trade War, and a highly troubled property sector and job market.

Diving into some of the trends that we consider will characterize the region for the near future we start with Intra-Asia trade which as described by the KKR Insights team, it reflects the Asia’s increasing economic integration as regional trade recently surpassed 55% of total flows, reinforcing domestic demand, supply chain realignment and broader capital formation, with such dynamics catalyzing investment into infrastructure logistics and digital capacity. The second trend we observe is increased capital rotation into Asia as global allocators continue to reroute capital to the Asia ex. China segment as a strategy to capitalize on the region’s growth without over allocating to the increasingly complex Chinese market. This trend reflects a structural reallocation away from both the US and China and towards pan-Asian and mega-fund strategies. As the third leading trend, we see digital infrastructure as a core theme in Asia as it now represents a growing share of deal value, supported by Asia’s rapidly expanding demand for computing power and data capacity. However, this does not come without risks, as geopolitical frictions, supply-chain fragmentation, and outbound investment controls, particularly in sectors such as AI and semiconductors, add complexity for PE managers navigating the region.

Diving into the fundraising environment in Asia, we observe divergent signals: despite substantial deal value and inflows, the broader fundraising backdrop remains challenging. This trend was evident in 2025, when it declined by 29% to a 12-year low as LPs sought to moderate their China exposure in the wake of a new global trade backdrop. However, despite the relatively low fundraising numbers, there are two leading trends, starting with Pan-Asia mandates which grew to 60% of new capital raising in the region (up from 36% in 2019), which reflects LPs interest in diversifying to other rapidly growing economies such as the case of India and Southeast Asia at the same time investors can tap into Japan’s new fiscal changes which boost the competitiveness of the nation. The second trend we observe is that Mega-funds continue to dominate and even double down on fundraising for Asia-Pacific-focused strategies, as we can see in the following examples of fundraising activity:

- KKR closed a record $12Bn Asia fund, targeting Japan carve-outs, India growth, and Southeast Asia infrastructure and credit

- Blackstone raised $10Bn for its Asia buyout platform, focused on control, energy efficiency, and infrastructure.

- EQT launched $1Bn Asia Green Transition Fund targeting renewable energy

Inside the Asian private equity environment, we can observe numerous divergences in the paths and trends that each country has taken and how that is affecting the general landscape:

India: A Core Engine of Growth and Exits

- India has become one of Asia’s most dynamic PE markets, with a 2024 deal value rising to $42Bn and buyouts accounting for 51% of total deal flow. Some of the drivers we observe in the region are the rapid digitalization and high-growth consumer markets, which continue to anchor deployment. We also see government reforms that have streamlined deal origination and exit processes, and ultimately, a robust IPO ecosystem that now represents half of all PE exits and supports rapid capital recycling.

Japan: Carve-Outs, Governance Reforms, and Take-Privates

- Japan’s PE market is undergoing a major structural expansion, supported by corporate governance reforms over the past few years, the yen’s depreciation, activist pressure, and the election of its new Prime Minister, Sanae Takachi, who is set to continue late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s economic reforms. Some of the leading drivers in the Asia PE market are industrial and retail carve-outs and SME succession deals, which dominate transaction themes. In addition, a weak Yen backdrop enhances LBO economics and foreign sponsor competitiveness, and ultimately, the country faces a significantly improved governance environment that supports operational changes and divestitures.

Southeast Asia: Selectivity, Secondaries and Green Economy Growth

- This is a different region, as it falls into the recent player category in the Asia PE landscape, with fewer deals but higher value exits; the Q1 2025 exit value was up 50% YoY to $679mm. Some of the drivers in the Southeast Asian market include strong momentum in private credit and green economy investments, as well as sponsors prioritizing operational improvement over pure-play strategies. Another aspect we observe is an increase in cross-border cash flows, with Singapore, Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines acting as regional hubs.

China: An Enormous Market Dragged by Regulatory Burdens

- A section of the Asian private equity market we cannot ignore is China, which, despite its larger and historically dominant position, continues to face regulatory headwinds and stagnant exit opportunities amid US-China trade friction, outbound investment controls, and heightened compliance scrutiny. While large-scale transactions have slowed, sponsors are shifting towards consumer, renewables, and health tech, where selective opportunities persist. Some of the trends we see are a narrowing sector focus as investment in AI and advanced manufacturing remains highly complex. In this backdrop, secondaries are becoming increasingly crucial as IPO windows remain narrow and regulatory actions pressure valuations.

KKR’s Asia Pivot: Half of Global PE Distributions, Strategic Platform Exits in India and Japan

In the existing backdrop, KKR marked a pivotal moment in 2025 as its Asia investing platform generated more than half of the firm’s global private equity distributions for the first time. This outcome reflects a multi-year repositioning toward the region, underpinned by calibrated deployment, accelerated exits in India and Japan, and a broader shift in global capital flows toward Asia’s control-oriented opportunities. However, in this case, the focus shifts to Japan, India, and Southeast Asia as the firm seeks to reduce portfolio concentrations in the United States and China.

As the first market we observe in this case, India remains central to KKR’s distribution performance, as it is supported by one of the strongest IPO markets globally. Some of the leading transactions in the India-PE market include the divestment of Max Healthcare, valued at $1.3Bn after a successful listing and subsequent secondary placements. Strong public demand and institutional liquidity enabled rapid capital recycling, enabling India to contribute nearly one-third of KKR’s regional distributions.

As the second market we observe in KKR’s new Asia playbook, Japan has come to the spotlight due to its reviving M&A market and positive prospects. Japan delivered a complementary exit regime, driven by depressed public valuations, a 16% depreciation of the yen, and continued governance reforms that encourage divestitures, transparency, and capital efficiency. On the Japanese market, KKR executed several high-profile carve-outs and succession-driven take-privates, including the divestment of Hitachi Kokusai Electric after a multi-year operational repositioning.

Diving into the deal capital impact and performance outcomes, Asia generated more than $6in distributions for KKR in the latest fiscal period, with over 60% derived from IPOs, strategic secondaries, and trade sales concentrated in India and Japan. This contributed to the firm’s best-in-class DPI and IRR metrics, exceeding US and European benchmarks by 200-400 bps. For the Asian ventures, performance was driven by three reinforcing dynamics: India’s rapid exit volatility through public markets, Japan’s expanding supply and carve-out succession transactions, and disciplined exposure to digital infrastructure and other long-duration assets.

Opportunities: corporate carve-outs, take-privates, digital & green growth

We identify three key zones as the next frontier in Asia’s PE landscape: corporate carve-outs, take-private transactions, and digital/green growth assets.

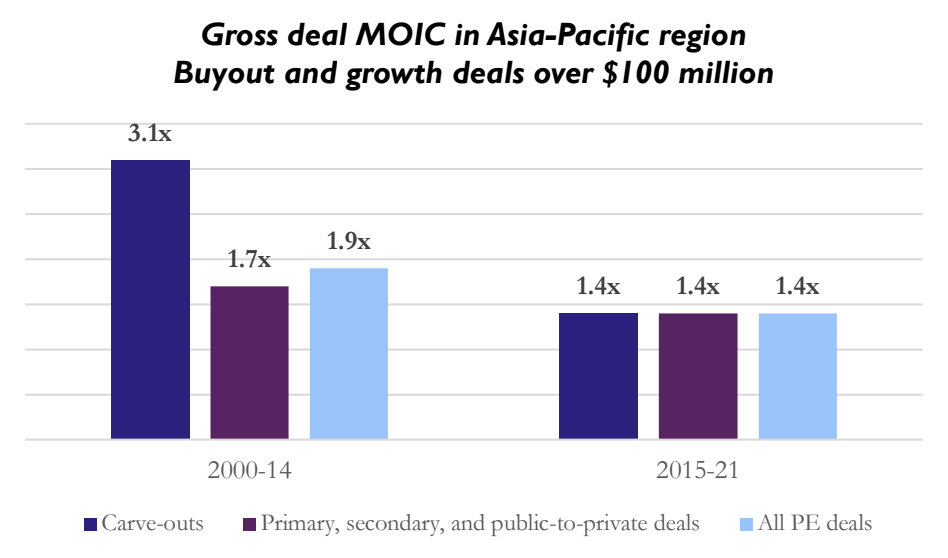

Corporate carve-outs (the divestment of a business unit by a larger firm) are becoming one of the most active deal types in the Asia-Pacific region at 20% of all buyouts over $100mm in 2024. This is driven largely by conglomerates in Japan, India, and South Korea rationalising operations or facing regulatory pressures to shed non-core assets creating a rich pipeline of mid-sized, cash-generating targets attractive to PE funds looking for control deals. However, increased competition and elevated multiples have made it harder compared to past years to deliver strong returns on these complex transactions, eroding the premium MOICs we have seen previously.

Take-private deals similarly offer control, flexibility of operating outside public scrutiny, and margin-optimisation levers for GPs, especially in markets where public valuations are depressed and the regulatory frameworks tend to favour privatisation deals. In Japan, for instance, weak equity performance and corporate governance reforms have encouraged management buyouts, with a record number of take-private transactions in 2024. In India and South Korea particularly, family-owned or founder-led firms facing succession planning challenges have also become prime targets for such transactions, enabling PE firms to unlock trapped value in these under-researched mid-cap segments.

Key broader trends we see as tailwinds for growth are digital infrastructure (data centres, cloud computing, telecom networks) and green-economy assets (renewables, sustainable manufacturing, circular economy. The region’s rapid rise in data consumption, expanding e-commerce penetration, and AI adoption are increasingly fuelling demand for digital capacity, particularly in India, Japan, and Southeast Asia. For instance, KKR & Co.’s co-CEO recently highlighted data-centre infrastructure as a major strategic theme for Asia amid a weakening U.S. dollar and deepening digitalisation. Emphasising this conviction, KKR and Singtel [SGX: Z74] are in the process to acquire over 80% of ST Telemedia Global Data Centres for $3.9bn, motivated by internet-traffic growth and long-term lease stability as key drivers of predictable returns.

Similarly, green growth is drawing in a host of long-horizon investors. Asia is projected to account for nearly 50% of global renewable-energy investment by 2030, with governments in India, Indonesia, and Japan accelerating the transition to clean-energy through subsidies and carbon-credit frameworks. PE funds are increasingly aligning with these policy shifts: Blackstone’s [NYSE: BX] US$10bn Asia buy-out fund, for example, explicitly earmarks capital for energy-efficiency and decarbonisation assets, while EQT’s [NYSE: EQT] Asia Green Transition Fund has raised over $1bn in commitments.

Capital redirection from the US to Asia

One of the most significant structural tailwinds for Asia’s private equity ecosystem is the combined effect of a weakening dollar and a shift among global investors away from the US, and towards Asia’s stronger fundamentals and expanding long-term growth opportunities.

This reallocation away from the United States is driven by rising macroeconomic and policy uncertainty in American markets, as mounting fiscal deficits, erratic trade and policy decisions, and political friction over spending and taxation have weakened investor confidence. Meanwhile, recent rate cuts by the Federal Reserve and expectations of further easing through 2026 exerted sustained downward pressure on the U.S. dollar, which has fallen roughly 6% from its 2024 highs against a basket of major Asian currencies. A softer dollar boosts the relative returns of overseas assets, making Asia’s equity and private-market opportunities increasingly attractive to global LPs.

Evidence of the capital rotation is already visible: Goldman Sachs’ [NYSE: GS] Kevin Sneader reported approximately $100bn of inflows into Asia (excluding China) over the nine months to October 2025, highlighting technology, consumer, industrials, and private healthcare as the sectors drawing the most attention.

Mega-funds are also behaving consistently with this trend. Blackstone has reached its $10bn target for its latest Asia buyout vehicle and is guiding to a $12.9bn hard cap at final close, citing strong traction in India and Japan despite a globally challenging fundraising environment. In particular, India has emerged as the region’s standout performer, being the only market in Asia-Pacific to record double-digit growth in deal value and volume in 2024, with buyouts rising to 51% of total PE activity.

Key Risks

Next, we outline a few key risks affecting Asia’s private equity market, starting with PE-specific challenges and moving on to global macroeconomic pressures that could influence performance and capital flows in the region.

Fragile IPO Windows: Although IPO activity across Southeast Asia is reaching record levels, the conditions to sustain this activity are still fragile and short-lived. In public markets, investor sentiment remains subdued mainly by persistent volatility and geopolitical tensions; this could risk weakening the demand for new listings, consequently constraining one of private equity’s most important exit routes. We saw this last year, as Asia-Pacific’s IPO-exit value dropped to roughly 31% of total exit value, well below the five-year average of about 48%. With limited opportunities to monetise portfolio holdings through public listings, PE firms may have to increasingly turn to secondary and trade sales, often at compressed valuations or with longer holding periods.

Fundraising slow-down: Asia-Pacific PE fundraising declined by 29% in 2024 to its lowest level in 12 years (excluding RMB-denominated funds), as global LPs grew more selective in their allocations amid ongoing US-China trade tensions, tighter outbound investment restrictions, and a weak exit environment. As a result, much of the capital once earmarked for China has been redirected to home markets or toward India and Japan, where deal activity remains strong. Amidst this macroeconomic uncertainty, most investors gravitated towards established managers such as KKR, while first-time funds struggled to close.

Valuation inflation: As more capital competes for attractive deals, valuations in leading markets such as Japan, India, and South Korea have become increasingly expensive. According to Bain & Company, the performance gap between the best and weakest funds has widened sharply: top-quartile Asia PE funds from the 2017 vintage delivered returns above 25%, while those in the bottom quartile achieved only high single-digit IRRs. This growing rift shows how premium entry valuations are making it harder for some lesser disciplined investors to generate strong returns.

Interest-rate and debt environment: Since most PE deals rely heavily on leverage, higher interest rates increase the cost of financing and compress returns. As global growth slows, companies face weaker earnings, tighter credit conditions, and reduced investor confidence, all of which heighten refinancing risk, making it more difficult and expensive to roll over existing debt as it matures.

Geopolitics and supply-chain shifts: Intensifying trade tensions between the US and China, along with regional frictions across Asia, significantly impact global trade flows and investment policy. Such geopolitical dynamics can create both direct and indirect risks for private equity investors. On one hand, such tensions may disrupt cross-border supply chains and temporarily impair the operations of portfolio companies. On the other, outbound investment restrictions, tighter regulations, or national-security restrictions particularly in sectors such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and advanced manufacturing, where many Asian firms are deeply embedded, could complicate compliance and thus reduce investment feasibility.

Currency fluctuations: Although a weaker dollar currently provides global PE firms with a relative advantage when deploying capital in Asia, exchange-rate volatility remains a significant risk over the investment horizon. A renewed dollar appreciation could quickly reverse these gains, eroding exit valuations and portfolio returns. This introduces an additional layer of macroeconomic complexity for investors, particularly given Asia’s highly diverse currency landscape in contrast to the more unified markets of the US, EU, or UK.

Conclusion

In summary, amidst the global uncertainty and the steady diversification of capital away from the United States, Asia has become one of the most resilient and promising regions for private equity deployment. The region’s structural advantages are a combination of macroeconomic stability, demographic tailwinds, and supportive policy reforms to attract long-term investors.

Going forward, corporate carve-outs are to be the most prominent deal type, providing control opportunities and operational upside as conglomerates seek to streamline their operations. Take-privates are also on the rise, driven by corporate governance reforms (especially in Japan), and widening valuation gaps between public and private markets. At the same time, digital infrastructure and green-economy assets are driving a new cycle of investment, supported by strong regional demand for data capacity, renewable energy, and sustainable manufacturing.

Investors must remain wary of fragile IPO windows in Asia, which could significantly affect their exit plans and valuations. Moreover, PE fundraising in the region is rebounding, reaching new highs after a subdued 2024. Still, investors must manage risks arising from geopolitical tensions, valuation inflation, and currency swings, which most global and regional funds are addressing by deploying resources toward disciplined research and building localized expertise. With many leading managers showing early conviction, and governments across India, Japan, and Southeast Asia steadily developing regulatory frameworks to attract private capital, Asia’s private equity market is well positioned to deliver strong, risk-adjusted returns, and potentially outperform peers in the foreseeable future.

0 Comments