Introduction

The creator of Ozempic, the American pharma giant, biotech start-up, bid after bid, boardrooms and courtrooms… Yes, as you’ve probably guessed already, this article will be talking about the unprecedented takeover battle in pharma sector. Novo Nordisk and Pfizer have put everything on the table in their fight to get a larger share of the booming obesity drug market through the acquisition of Metsera. In this article we will explore the strategies and offer structures applied in this battle, as well as analyse why Metsera has become such an appealing target, evaluating the company through JPMorgan’s global takeover candidates framework.

Takeover Battle

“The first rule of business is: protect your investment.” – Jerry Maguire (1996)

COVID-19 pumped billions into the pharmaceutical industry as countries required effective vaccines to return to normalcy. Firms such as Pfizer [NYSE: PFO] and Novo Nordisk [CSE: NOVO-B] profited a lot, leading to significant increases in share prices. In 2022, as COVID-19 faded, Pfizer and Novo Nordisk diverged. While Pfizer was unable to innovate and counter declining COVID-19 product sales, Novo Nordisk experienced explosive growth from its new drug, Semaglutide, better known as Wegovy or Ozempic. These semaglutides help regulate insulin production by the pancreas. The real cash cow of this medicine was its weight-loss properties. This medicine reduces food cravings and increases feelings of fullness. As this product became popular, supply could not keep up with demand, leading to eye-watering prices that pushed Novo Nordisk’s net income from roughly $4.6bn in 2021 to $7.6bn in 2023. Pfizer, like many other pharmaceutical companies including Eli Lilly [NYSE: LLY], began pushing heavily into this field. They attempted to create a pill version (rather than an injection equivalent), named danuglipron. It failed in trials and was discontinued in 2025 due to severe gastrointestinal side effects and an overall concern for long-term impacts on the liver.

In a bid to regain momentum and break into this highly competitive and lucrative market, Pfizer submitted an all-cash bid of $4.9bn-$7.3bn on the 22nd of September for Metsera, a pharmaceutical company focused on developing therapies that regulate gut hormones and thereby influence appetite. This offer would buy shares at $47.50, including incentives that could add $22.50 per share of contingent value rights (CVRs) if specific criteria are met for their drugs MET-097i and MET-233i, such as entering phase 3 of clinical trials or obtaining FDA approval. CVRs are simply contracts that guarantee future cash payments if objectives are met. This offer was accepted but quickly started an arduous back-and-forth. Facing pressure from Eli Lilly’s advances and potential future competition from Pfizer, Novo Nordisk submitted a peculiar unsolicited offer on the 30th of October. Rather than the traditional bid structure, where either stock or cash-based compensation buys every share, Novo Nordisk’s bid had a two-step structure: they would buy roughly 50% of Metseras’ shares (specifically non-voting preferred shares) at $56.50 per share, around $6.5bn in total (value of all the shares, not just 50%). The rationale behind purchasing non-voting shares was simple: to prevent the FTC from intervening in a takeover and to protect the Metsera board’s fiduciary responsibilities. After passing regulatory and shareholder approval, Novo Nordisk could buy out the remaining shareholders and fully assume control of the firm. They would then provide an additional $21.25 per share of CVRs, bringing the total potential value of this offer to roughly $9bn. This unusual structure was uniquely suited to Novo Nordisk’s position. Regulatory entities try to maintain competitive markets. A traditional all-cash merger would have certainly faced severe scrutiny. Regulators would have sought to block Novo Nordisk to create a more open market, specifically for obesity and weight-loss drugs. This offer showed how serious Novo Nordisk was, as it significantly increased total compensation, committed capital immediately (usually cash or stock is exchanged after regulatory approval, not after signing), and respected the shareholder process. Therefore, Metseras’ board opened discussions.

“Something is clearly rotten in the state of Denmark” – Hamlet (Shakespeare)

Pfizer immediately sued, claiming antitrust violations and contract violations. Legally, it seemed Pfizer was losing, as the courts rejected its claims and petitions to stop this process. Politically, however, Pfizer appeared to have the upper hand as the US firm had a good relationship with President Trump due to previous dealings with the TrumpRx drug platform. It seemed highly unlikely that a pro-American Government would ever allow a Danish firm to export innovation abroad and shut Pfizer out of the market. On the 4th of November, Novo Nordisk upped its offer to $62.20 per share plus $24.00 in CVRs, bringing the total to roughly $10bn. This may seem counterintuitive: why should a firm with a bid already higher than its competitors raise it again? The answer is simple: regulation. This deal structure inherently went against any form of overview. Metsera signed a definitive, binding merger agreement. To accept this deal, Metsera would need to prove that the offer was superior and give Pfizer the ability to match. This led Novo Nordisk to work with regulators to standardize its offer, ensuring it was fully binding and included committed financing. This would provide the certainty needed for the deal to pass and force Pfizer to the table. Metsera’s board commented that this bid was a ‘Superior Company Proposal”. Pfizer quickly matched the offer at $65.60 per share plus $20.65 in CVRs, offering slightly more value but notably more upfront capital. Metsera chose to accept the Pfizer offer over Novo Nordisk’s mainly due to feasibility concerns. In calls with FTC officials, Metsera determined that the Novo Nordisk offer “presents unacceptably high legal and regulatory risks”. Ultimately, Novo Nordisk walked away from negotiations, likely due to the aforementioned regulatory headaches and the trimming of financial upside that occurred through these negotiations. An interesting aspect of this battle is the intensity and ferocity of Pfizer’s statements against Novo Nordisk. For established competitors to begin clashing at these scales, calling bids illegal and old-fashioned clearly reflects the competitive, cutthroat environment in the obesity and weight-loss market.

Who Wins and Who Loses?

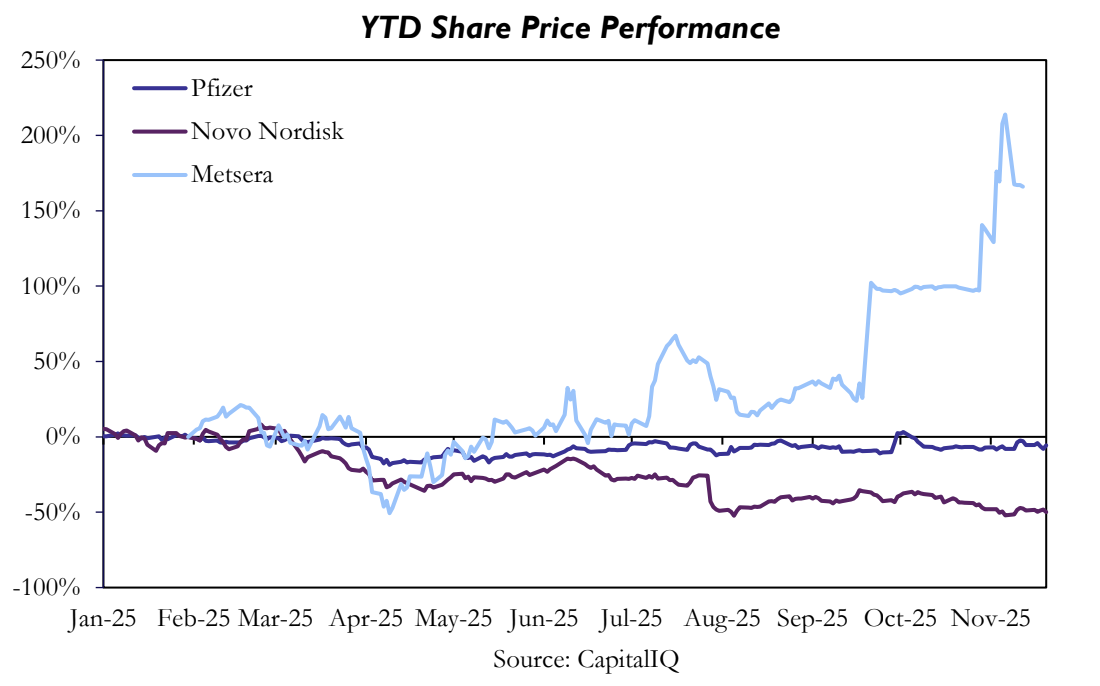

Metsera shareholders have been the clear winners of the takeover battle. The stock rose 288% in the ten months between its IPO and the deal’s completion, driven by the aggressive bidding war between two pharma giants. By contrast, Pfizer shares are roughly flat year to date, while Novo Nordisk has fallen by about 50%.

The deal offers Pfizer the chance to get some foothold in the highly lucrative obesity market. Metsera’s obesity pipeline can help the company gain share in a market forecasted to exceed $100bn in the early 2030s, helping to replace declining COVID-era revenues. With roughly three quarters of the deal paid upfront as cash, Pfizer is making a strong bet on the obesity market. Concerns over intensifying GLP-1 competition, coupled with management’s guidance cuts, have weighed heavily on Novo Nordisk’s share price performance YTD. However, shares were up 3.5% on the day when Novo Nordisk announced its withdrawal from the bidding war. The move was interpreted as a strategic decision to avoid overpaying in a competitive auction, partially relieving investors’ concerns around obesity market overdependency and bidding escalation.

Novo Nordisk’s approach to M&A has changed significantly over the last five years. Historically, the company relied heavily on its internal R&D pipeline. That stance began to shift in 2020, with the acquisition of Corvidia Therapeutics, and deal activity has accelerated since 2022. Novo Nordisk is increasingly turning to M&A to bolster its pipeline in the core areas of obesity and diabetes. Recent M&A has also targeted more serious metabolic conditions, as well as cardiovascular and rare diseases. New CEO Mike Doustdar may continue to further broaden Novo Nordisk’s portfolio, which is currently heavily reliant on the obesity market. This is a weakness that has been exposed this year as Eli Lilly’s weight management drugs became more widely available in the US and took share from Novo Nordisk. Adding to competitive pressure, compounders (unbranded alternatives without FDA approval) have started to enter the US market, leading to price reductions in certain channels as Novo Nordisk report weaker than expected take up of its branded GLP-1s.

Novo Nordisk also faces pressure in weight management from patent expiration and government level price negotiations. The company’s primary patent for semaglutide is expected to expire in 2026, whilst secondary patents offer protection until 2031. As well as the patent cliff, Novo Nordisk faces a potential pricing cliff in 2027. Under the Inflation Reduction Act, pharmaceutical companies negotiated a maximum fair price for all semaglutide branded formulations. This price is yet to be disclosed but will put a ceiling on pricing for the company and will come into effect at the start of 2027.

To address this problem of GLP-1 overdependence, Novo Nordisk has begun to expand its pipeline beyond obesity and diabetes. The company acquired Cardior Pharmaceuticals in March 2024 for $1.1bn. Cardior’s lead candidate is an RNA-based therapy that targets cardiac disfunction which is currently in Phase 2 clinical development. In October 2025, Novo Nordisk also announced its acquisition of Akero Therapeutics for just under $5bn, expanding Novo Nordisk’s pipeline into more serious metabolic diseases. This broadening of the pipeline marks a strategy shift away from the core business and toward areas adjacent but distinct to obesity.

Future M&A may align more with this strategy of diversification. This in combination with the unsuccessful bid for Metsera makes Viking Therapeutics a potential target. Viking’s major pipeline is in GLP-1s for obesity and metabolic diseases however the company also has a program in stage 2b of clinical trials that targets more serious metabolic/liver diseases. Terns Pharmaceuticals is another potential candidate that would broaden Novo Nordisk’s metabolic disease pipeline beyond GLP-1s. Similar to Viking, Terns has a pipeline consisting of both GLP-1s and more serious cardiometabolic disorders. A deal of this nature represents a two-fold benefit to Novo Nordisk: deepening the GLP-1 pipeline and potentially diversifying the company’s drug portfolio. In the end, although Novo Nordisk lost the battle for Metsera, it preserved funds for potential future acquisitions in other areas, which may be seen by shareholders as a more favourable strategy that is not subject to antitrust issues.

Metsera as an Ultimate Takeover Target

To understand why there was such an intense battle for Metsera, we need to take a closer look at the company itself. Metsera is a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company that develops next-generation injectables and oral nutrient-stimulated hormone (NuSH) analogue peptides to treat obesity, overweight, and related conditions. Its product pipeline includes drugs in Phase 2 and Phase 1. The company was founded by Clive A. Meanwell in June 2022 and went public on NASDAQ in January 2025. It’s worth mentioning that, in 2023, Metsera bought an obesity drug start-up from an Imperial College professor for approximately $114m. Although Metsera is now backed by U.S. venture capital firms Arch Venture Partners and Population Health Partners, it was British scientists who conducted the research that led to one of the most dramatic pharma battles in years.

The rationale behind such high demand for the biotech start-up is clear: Metsera has one of the most promising pipelines of obesity treatments, which could help Novo Nordisk improve its weakening position compared to Eli Lilly in a market where it was once an unbeatable leader. Meanwhile, a win for Pfizer could allow the company to increase its market share in the obesity drugs market after its in-house-developed solution failed in clinical trials earlier this year; all subject, of course, to the success of Metsera’s drugs. Through this acquisition, Pfizer has added a portfolio of promising therapeutic candidates that complement its Internal Medicine pipeline, including MET-097i, a weekly and monthly injectable GLP-1 receptor agonist (RA) nearing Phase 3 development; MET-233i, a monthly amylin analogue candidate being evaluated both as monotherapy and in combination with MET-097i in Phase 1 development; an oral GLP-1 RA candidate in Phase 1 development; and additional preclinical nutrient-stimulated hormone therapeutics – quite an impressive portfolio.

Having explained the rationale behind both bidders, we will now look at Metsera from another perspective by evaluating the company through JPMorgan’s Global Takeover Candidates framework. Before we begin, let us briefly introduce this research. JPMorgan’s Global Equity Quantitative Analysis desk rates 2,506 companies based on the likelihood of them receiving a takeover offer. Each potential target receives a score from 0 to 1 for the following 4 factors: industry turbulence, misvaluation hypothesis, inefficient management, and growth/resource mismatch.

For instance, a company receives 1 point for the misvaluation factor if its P/E ratio is lower than the sector median and its book value is higher than its market value, while a score of 0.5 is given when only one of these two conditions is met. Similarly, a candidate receives a maximum score on the inefficient management, or so-called “Sub-optimal Use of Resources” factor when its 3-year stock return is below its national index return and its t3-year ROA is below the sector median; a score of 0.5 is assigned when only one criterion is satisfied. According to the growth/resource mismatch factor, a full score is given to a company that has high liquidity and low leverage with low sales growth, or low liquidity and high leverage with high sales growth – both cases suggesting an imbalance between financial capacity and expansion pace. Lastly, a candidate receives 1 point for the industry turbulence factor if it operates in a sector that has seen more takeovers in the past year than the average of the previous five years. Given the recent decrease in the number of takeover approaches, all companies in the screening sample received a score of 0 for this criterion. This explains why the maximum total score assigned in the current framework was 2.5 points.

To gain a better understanding of the framework, let us analyse Pfizer’s score. The US pharma giant received its only point for the sub-optimal use of resources factor because its share price has fallen 54% since November 2022, while the S&P 500 has risen 62% over the same period. Moreover, Pfizer’s 3-year average ROA is 7.08%, compared with the industry median of around 9%. At the same time, its price-to-book ratio is much lower than its P/E ratio, and sales growth and leverage are high, while liquidity is low – meaning that Pfizer does not fall under the misvaluation or growth/resource mismatch criteria.

Having reviewed Pfizer, let us now analyse Metsera according to this framework. This, however, is not an easy task, as Metsera is a clinical-stage start-up with no revenues, which means it reports a net loss rather than income. Therefore, there is little sense in looking at P/E or EV/EBITDA ratios, as all of them are negative. What we can say with certainty is that the company was definitely not undervalued at the time of its sale to Pfizer. The bidding war raised the deal value from an initial $7.3bn to up to $10bn – all for a company that has yet to become profitable. Furthermore, Metsera’s share price skyrocketed from $18 at its IPO in January 2025 to $70.5 at the deal close on November 13, marking a 292% increase in less than a year – hardly a sign of mismanagement. Therefore, according to the JPMorgan framework, Metsera would likely receive a zero score, suggesting that the rationale behind the takeover was different in this case.

The company became an acquisition target not because of inefficient management or a growth/resource mismatch, but due to its outstanding R&D capabilities, which represent a strategic milestone for the acquirer. “It’s a deliberate investment in the future of medicine. By acquiring Metsera, we are directing our resources toward one of the most impactful and high-growth therapeutic areas and positioning ourselves to define it,” said Albert Bourla, Pfizer Chairman and CEO. To conclude, although the transaction is expected to be dilutive through 2030, it represents a strategic milestone for Pfizer and will hopefully lead to breakthrough developments in medicine. While it remains to be seen whether Metsera’s pipeline will live up to expectations, it is safe to say that this was one of the most thrilling takeover battles in recent years.

0 Comments