Introduction

“Everything is connected; everything is a balance.” – The Giver

In the 1850s, as technologies improved, the world underwent a drastic shift from a set of largely independent economies to a single, intertwined global economy. Ease of transport (through greater integration and innovation, such as steamships and railroads), interconnected financial institutions, a largely peaceful world order, and a biblical migration of individuals all facilitated the creation of the “world economy” in which capital was allocated more efficiently. Globalization drives down prices as costly barriers are removed, and open-market economics come into play. This first wave of globalization came to a tragic close with WW1, slashing away any proverbial “bridges” leading to an era of intense protectionism and deglobalization. It took the US economy’s post-WW2 stability and stewardship for globalization to begin anew (specifically post-80s). This article will delve into recent developments in world integration and explain why/how the 2nd wave of deglobalization has begun. We will explore the effects of this decoupling on the financial landscape, IPO, and M&A markets.

Instigating Factors

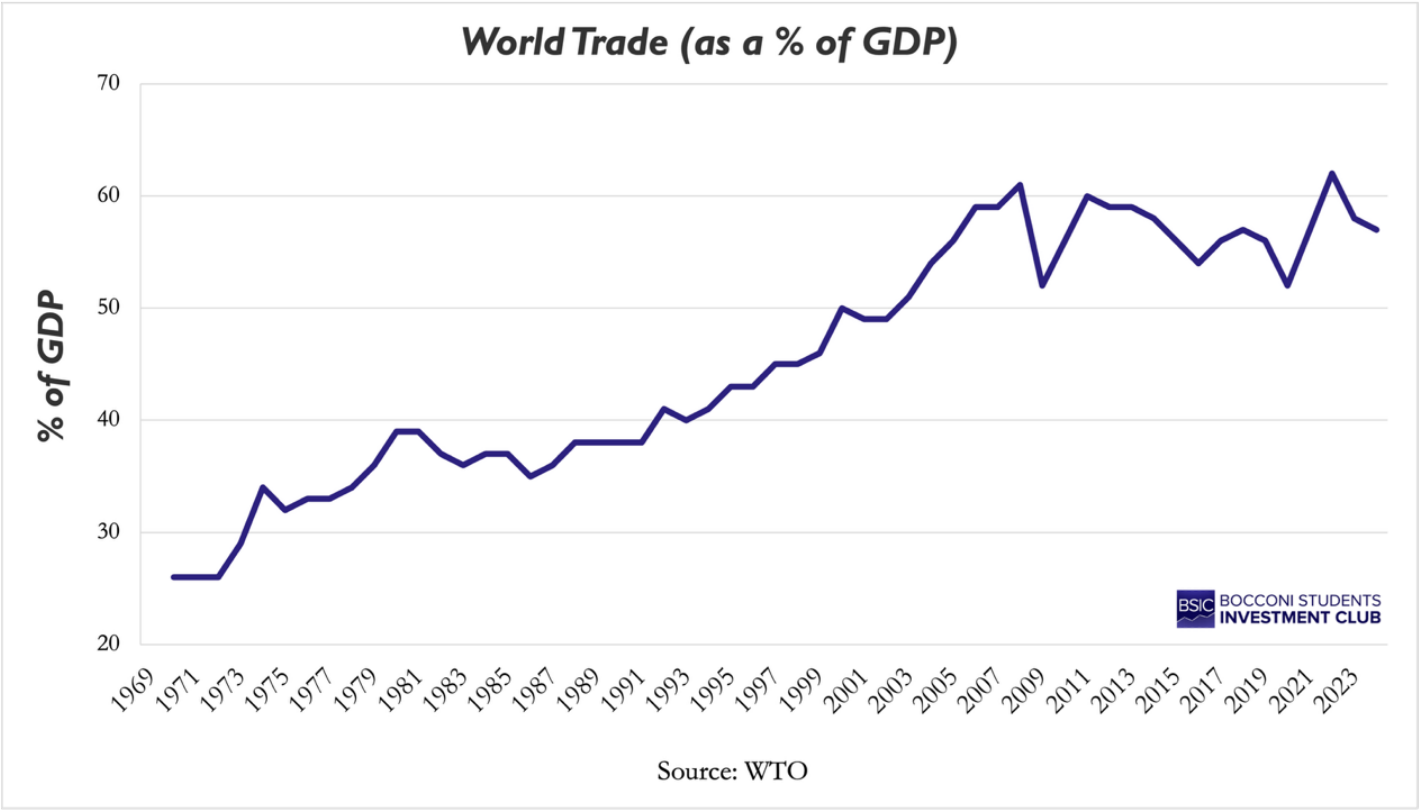

World trade integration surged in the late 20th century but has declined over the past decade. After peaking at about 60% of world GDP in both 2008 and 2022, it fell to 52% in 2020 and 57% in 2024. Unlike the interwar period, today’s deglobalization is subtler, as nations remain interconnected but are increasingly cautious about whom they trade with. Many are now prioritizing secure partners over the lowest cost suppliers. Policymakers promote concepts such as “friendshoring”, meaning rerouting supply chains to allied countries for security, as seen in recent US proposals. Although countries are not disengaging from international trade altogether, they are increasingly focusing on risk aversion.

The recent trend towards deglobalization is mainly driven by current geopolitical instabilities. An example of this is the “America First” trade policy, adopted by the US under President Trump. It centers on national priority, raising tariffs on foreign goods and renegotiating existing agreements. As the US retreated from multilateral engagement, supply chains were disrupted, and long-term alliances became strained. Furthermore, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 caused a sudden shock to the political and economic environment. The war triggered Western sanctions and global disengagement from Russia’s economy, specifically in Europe’s energy sector. Around the world, governments and companies severed ties with Russia, forcing a sudden restructuring of supply chains. These events highlighted the potential risk that geopolitical instability poses to trade. Since then, international relations have grown more volatile, making nations and investors increasingly hesitant.

The COVID-19 pandemic further raised doubts about globalized supply chains. Practically overnight, factories had to shut down, and ports slowed. Many countries found themselves without critical goods, whose production was concentrated abroad and could not be imported. Companies and governments realized that prioritizing low-cost, offshore production poses significant risks if some of these crucial links break. Those global supply disruptions further highlighted vulnerabilities in essential sectors like healthcare. For instance, shortages of medical masks and medications occurred as demand, driven by uncertainty, spiked, and imports failed to keep up. Therefore, the pandemic reemphasized the importance of supply chain resilience, prompting governments to encourage “near-shoring” to prioritize reliability, thereby reversing the earlier trend toward globalization and cost efficiency.

Another factor driving deglobalization is the extent to which earlier globalization encouraged dependence on single suppliers for strategic commodities. In the past, firms and governments focused on cost efficiency when sourcing key inputs, which often resulted in concentrated supply chains. This structure is efficient during stable periods, but it becomes fragile as uncertainty and disruption risk rise, leading to greater diversification.

Further to the medical supply chains during COVID-19 and energy dependence during the Ukraine war, vulnerability was also visible in the case of semiconductors. Computer chips are used in consumer electronics, automobiles, industrial machinery, and defense technology, so disruption affects far more than a single sector. Yet advanced chip production remains heavily concentrated in Taiwan, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company [NYSE: TSM] controls more than half of the global chip market, creating a chokepoint. A disruption in one region can constrain global supply and force downstream firms to reduce output. As semiconductors are also essential to modern military systems, communications infrastructure, and industrial automation, dependence on a concentrated supplier base is difficult to justify on efficiency grounds alone. This explains why the US and Europe have prioritized policies to expand domestic chip production and reduce single-point exposure, even though building local capacity is expensive. Therefore, the current deglobalization is driven by a reassessment of strategic dependence, which is increasingly viewed less as an efficiency gain and more as a vulnerability.

Impacts on the Financial Ecosystem

Deglobalization comes with several layers of risk: rapid policy changes, increasing regulations, trade restrictions, and enduring global conflicts introduce frictions into capital allocation and the operations of financial channels. Most importantly, these factors are not firm- or sector-specific; they inevitably have global consequences, making the risk systemic and harder to diversify away. This is why, historically, in periods of greater geopolitical fragmentation and global instability, investors tend to require higher risk premia to compensate for heightened uncertainty. Financial theory relies on this fundamental trade-off between risk and return: with greater cash-flow volatility, investors become less confident in stable growth assumptions; discount rates rise, credit spreads widen, and the Cost of Capital increases, ultimately causing valuations to fall.

Yet, contrary to expectations, financial markets currently remain resilient. In fact, this wave of deglobalization is building a new pattern for the redistribution of risk and capital across sectors, driven by three main features of the broader economic environment.

Firstly, index composition. Indexes are often concentrated, with few firms fundamentally affecting the overall performance. Moreover, the main players often operate in digital or highly scalable sectors, where they have strong margins, consistent earnings growth, and pricing power, and are less subject to physical trade barriers. Consequently, the indexes’ performance could be more representative of the resilience of these few firms than of the highly fragmented overall economy.

Secondly, new demand in strategic industries was created by deglobalization itself. In fact, global fragmentation increases perceived security risks and the danger of foreign supply chain disruption. Therefore, governments tend to increase spending to preserve domestic and economic soundness, favouring national champions in strategic sectors such as defence, cybersecurity, industrial automation, and domestic manufactures to limit dependence on external suppliers. For instance, global defence expenditure is expected to reach $2.6 trillion by the end of 2026, up 8% from the previous year. Such state-backed demand allows firms to benefit from long-term contracts and more stable support, thus reducing volatility and reinforcing expectations of revenue growth. Consequently, the market may be factoring in the enhancing effect of deglobalization on sustained public investments, rather than the disruptive forces it entails.

Thirdly, monetary policies. The upward pressure on risk premiums from geopolitical uncertainty and volatility is partially offset by central banks’ decisions worldwide. As inflation stabilizes, they might adopt less restrictive stances, gradually implementing rate cuts and supporting liquidity. Moreover, contained inflation helps firms stabilize cost structures, supporting earnings as well. Together with adequate market liquidity, these factors mitigate dramatic declines in asset valuations across fundamental sectors, limiting the impact of underlying structural fragmentation.

Implications for IPOs

IPOs clearly show how deglobalization affects capital markets. When international relations are stable, firms choose where to list mainly based on liquidity and valuation. However, as uncertainty rises, listing decisions are increasingly shaped by currency exposure, regulatory compatibility, and political risk. Companies are becoming more cautious about where they list their shares. US markets, such as the NYSE and Nasdaq, remain central because they offer scale, liquidity, and analyst coverage, but they’re no longer the default choice, as they were before. Firms whose revenues and costs are mainly in euros or Yuan may prefer a regional exchange to avoid rising exchange-rate volatility, especially when the market is already sensitive to geopolitical shocks.

Governments are now more willing to direct listings to jurisdictions where they retain oversight, or to financial centers aligned with their domestic policy goals. For example, recent reports indicate that Chinese regulators have become more cautious about US IPOs by smaller Chinese firms, particularly when listings are associated with price volatility or heightened sensitivity around regulatory oversight. Approval volumes have reportedly slowed relative to earlier periods, and review processes have lengthened. However, authorities appear to be encouraging more capital raising in Hong Kong, including secondary listings by large mainland companies. This implies that IPO geography is increasingly shaped by policy preferences rather than by market depth alone. Deglobalization also increases the requirements for going public. IPO readiness guidance emphasizes that issuers are expected to demonstrate stronger internal controls and more credible compliance frameworks, as underwriters and regulators perform more thorough diligence on legal and operational risks. Firms are increasingly assessed on their ability to manage sanctions, export control, and their corruption risk; all of which can materially affect valuation and execution. This results in longer preparation timelines, raising IPO costs.

Another example is the SEC’s new cybersecurity rules, which require fast reporting of incidents and more detailed risk management strategies. If these are underdeveloped, the listing process becomes more difficult, not only because of regulatory expectations, but also because investors increasingly consider cyber exposure in their risk assessments. The increasing market volatility further adds to these regulatory factors. As IPO execution risk increases, issuers are more likely to delay offerings until the conditions stabilize. Furthermore, policy shocks and regulatory changes can alter the feasibility of a listing plan, even when market sentiment is favorable, making IPOs less defined by valuation and more by jurisdictional fit. Although international listings remain possible, they are more dependent on political alignment and the credibility of governance and disclosure systems. Thus, IPO markets reflect the broader deglobalization trend, where access to global capital is increasingly shaped by the geopolitical environment.

Implications for M&A

While the financial market remains broadly resilient, stricter regulations and heightened political fragmentation continue to affect capital mobility, most evident in the M&A market. Cross-border deals face longer execution periods and are subject to stricter scrutiny, which analyzes not only industrial synergies but also geopolitical feasibility. Consequently, international deals are perceived as carrying a higher risk of non-execution, as they may be significantly constrained to protect national interests. In 2024 alone, the European Union screened 3,136 foreign investments, mostly in manufacturing and critical technologies, a 73% increase from 2023. Although only 1% of deals were ultimately blocked, longer and more thorough procedures might discourage international activity in favor of domestic transactions.

This structural shift particularly affects strategic industries, extending beyond the traditional defense or advanced technology sectors. Primary economic assets, including operations involving industrial capacity and sensitive physical locations, are now subject to more thorough national security scrutiny. As a result, transactions in sectors such as steel, semiconductors, energy infrastructure, and advanced manufacturing have become strategically important, and political feasibility has become a binding constraint in cross-border M&A.

Moreover, operations approval is also subject to the assessment of location risk. An example happened in Wyoming in 2024, where the crypto-mining site MineOne, linked to the Chinese government, was forced to divest its US operations by President Biden because of the facility’s location: it was close to a US Air Force Base, and the government determined that foreign control in the nearby area posed security concerns.

Tighter regulations extend to Europe as well. In 2024 the Chinese firm CSIC Longjiang GH Gas Turbine Co, linked to China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC) could not complete the acquisition of MAN Energy Solutions’ gas turbine business, a Volkswagen [FWB: VOW] subsidiary; the operation was blocked by German Economy Minister R. Habeck on grounds of national security, and such decision ultimately led Volkswagen to shut down the branch entirely.

However, not only has the definition of strategic widened, but control risk now extends beyond closing, as governments may intervene to regulate ongoing management and operations. A salient example is the semiconductor company Nexperia, which is owned by the Chinese company Wingtech Technology [SHA: 600745]. Since the firm is based in the Netherlands, the Dutch government has recently intervened in its corporate governance, arguing that Chinese ownership could erode vital capabilities for European economic security.

Although most deals are ultimately approved, stricter regulatory requirements and greater deal complexity are slowing execution. Empirical evidence shows that between 2018 and 2022, the signing-to-closing period for deals larger than $2 bn increased by 11%, and nearly 40% of operations failed to close on time. The UK National Security and Investment Act confirms such a trend. Between 2024 and 2025, of the 1,143 deals reviewed, 56 were paused for further investigation, 17 were restricted, and 1 was blocked. Moreover, once operations were formally investigated, it took around 70 days to formalize a final decision. The UK regime’s heavier intervention also increases execution risk: pausing or delaying transactions might affect potential synergies, financing costs, and expected earnings. Consequently, firms might have to incorporate timing uncertainty into valuation models and strategic outlooks.

Conclusion

The 2nd and 1st waves of deglobalization differ in structure. The scale and utter devastation of WW1 shattered ideals of international cooperation. At a basic level, WW1 broke the faith between countries through debt overhang and monetary chaos. Countries such as France and Britain were ravaged and had difficulty stomaching any concessions (necessary for collaboration) in the interwar period, even if, in the long run (and in many cases, the short run), they would benefit their economies more. There was a complete shift to nationalism, as international cooperation felt like a betrayal of politicians to their common citizens. This current wave is rooted in different, less severe shocks. International collaboration and trade are not shunned as much as they are critiqued. Firms and governments are now more wary of dependence on their partners and seek to develop trading relationships based on trust and safety, rather than simply on who provides the lowest prices. Looking ahead, deglobalization might create more stability as supply chains diversify, but it will also surely increase costs. For consumers, this is a mixed bag whose contents we will have to wait to truly learn.

0 Comments