Introduction

Japan’s general election on 8 February 2026 was the clearest political signal yet that the country is moving into a different macro regime from the one that defined the past two decades. Japan PM Takaichi achieved a historic victory as the LDP secured a two-thirds super majority in the 465-seat lower house by itself, the biggest number of seats any party has achieved in post-war Japan, providing her a strong mandate for her fiscal spending plans.

For much of the last 20 years, Japan looked like the textbook case of a low-inflation, low-growth equilibrium. Repeated shocks were met with monetary accommodation that compressed yields, flattened volatility and kept real rates deeply low. With wage growth weak and inflation expectations anchored near zero, fiscal policy oscillated between stimulus and consolidation but rarely changed the underlying dynamics; debt rose, yet debt service stayed manageable because yields stayed suppressed. For markets, the implication was simple: Japan exported capital, the yen often behaved as a funding currency.

The 2026 election matters because it arrives when that equilibrium is already under pressure. Inflation has become more persistent, wages are central to the narrative again, and the Bank of Japan is normalising policy (including the post-2024 shift away from strict yield control). Meanwhile, Takaichi’s mandate makes a larger fiscal impulse plausible and more durable than pre-election markets assumed. The result is a new triangle of risks and opportunities: higher domestic yields that could change global flow patterns, a more active fiscal state that could either lift nominal growth or raise a fiscal risk premium, and a yen whose direction increasingly depends on whether investors believe Japan can run “responsible but expansionary” policy without losing long-term credibility.

The Yen is still (mainly) a Rate Story

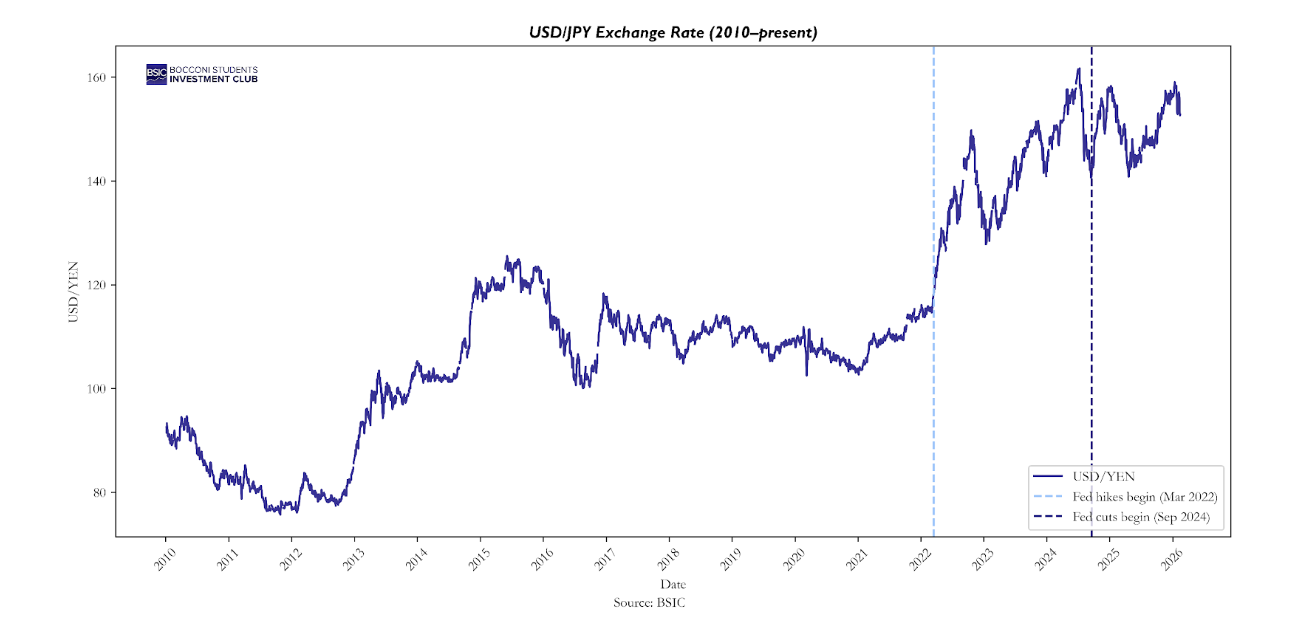

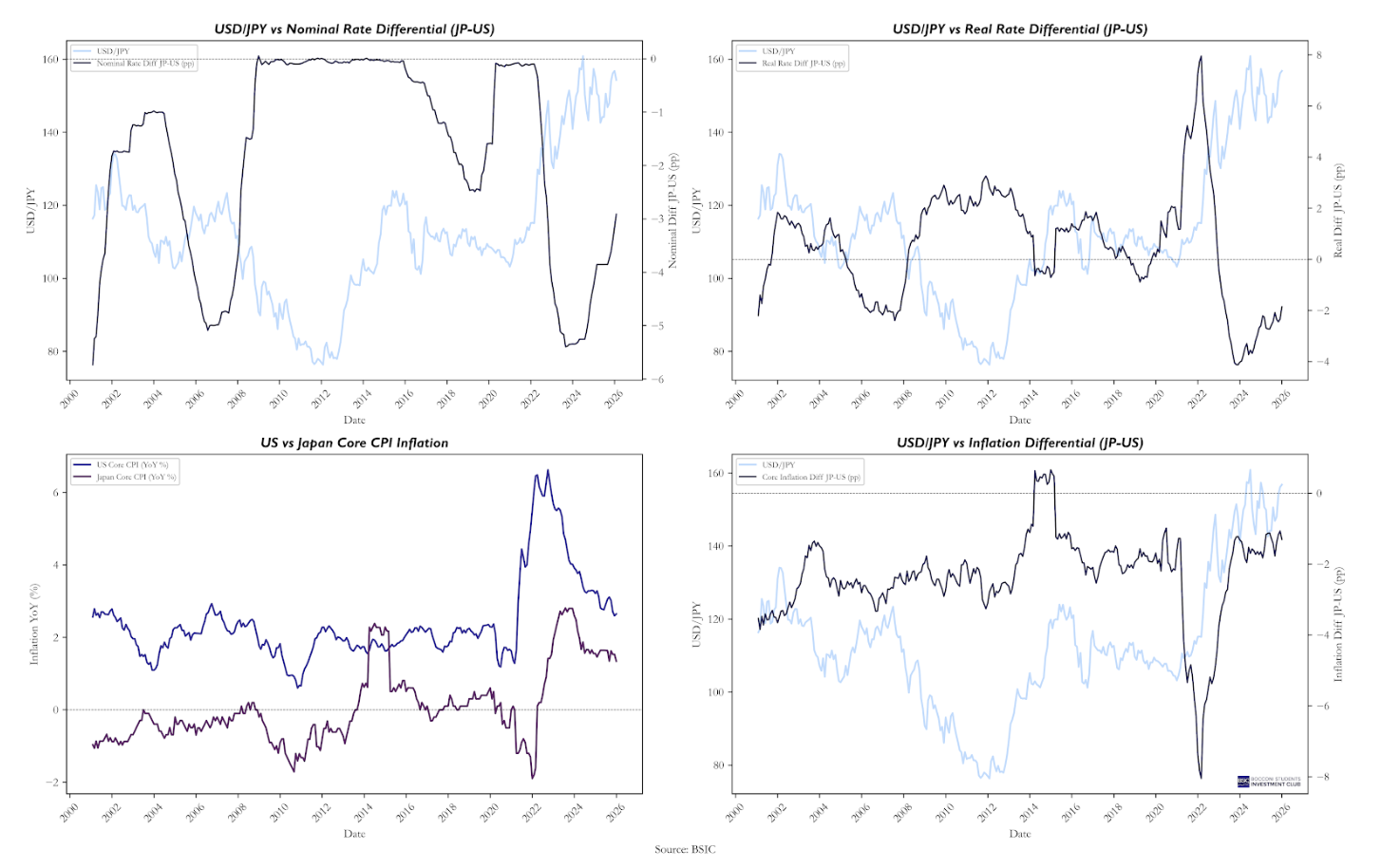

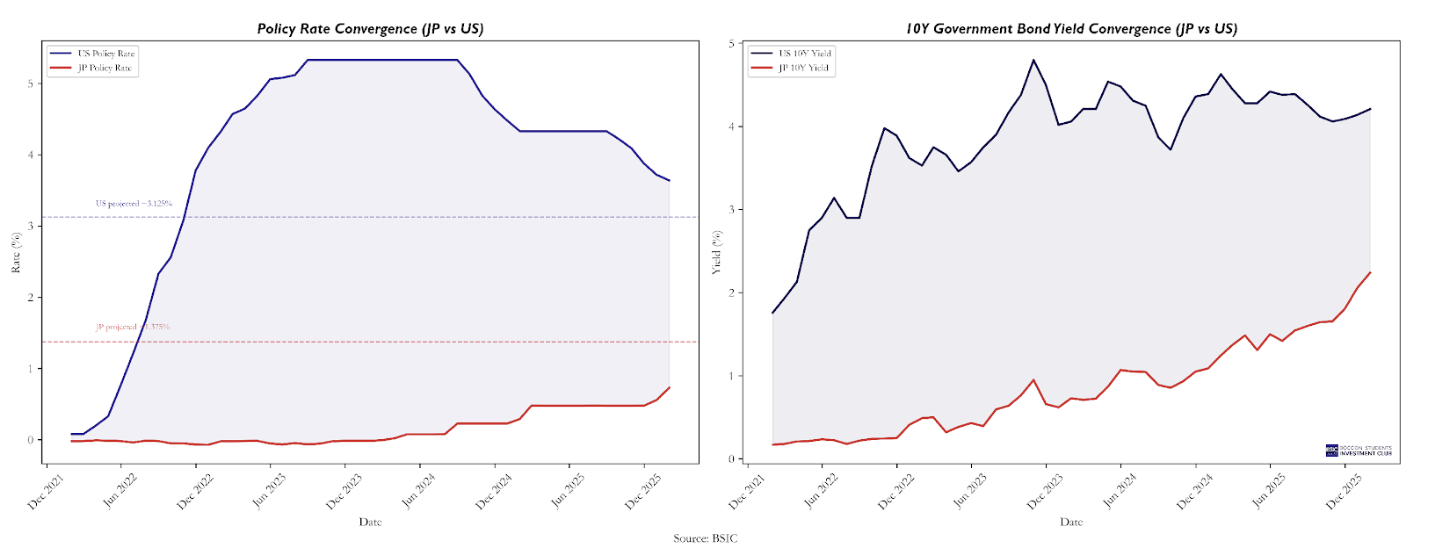

2022 saw a significant weakening of the yen due to Fed rate hikes. The period the yen started falling most quickly coincides with the Fed’s tightening cycle that began in March 2022. The policy differential shot up from around zero to over 500bp in 2023. The Fed’s rate was raised to 4.00%-4.25% at the fastest pace in decades. The exchange rate reacted violently, going from 115 to 149 in October 2022. Since then, it has been range-trading between 140 and 160.

The fundamental point to clarify here is the real rates differential, which is still in favor of the USD. Indeed, while the policy rate differential has narrowed from a spread of more than 500bp, it remains at around 300bp. At the beginning of 2022, U.S. core inflation was around 6%, while Japan’s was about 0.3%, resulting in a core inflation differential of roughly -7 percentage points. Because the inflation differential has largely closed, the real-rate gap has not tightened as much as many expected from the headline policy-rate convergence; with inflation no longer “erasing” US carry, a still-wide nominal spread translates into a still-supportive real return advantage for USD assets.

The fundamental point to clarify here is the real rates differential, which is still in favor of the USD. Indeed, while the policy rate differential has narrowed from a spread of more than 500bp, it remains at around 300bp. At the beginning of 2022, U.S. core inflation was around 6%, while Japan’s was about 0.3%, resulting in a core inflation differential of roughly -7 percentage points. Because the inflation differential has largely closed, the real-rate gap has not tightened as much as many expected from the headline policy-rate convergence; with inflation no longer “erasing” US carry, a still-wide nominal spread translates into a still-supportive real return advantage for USD assets.

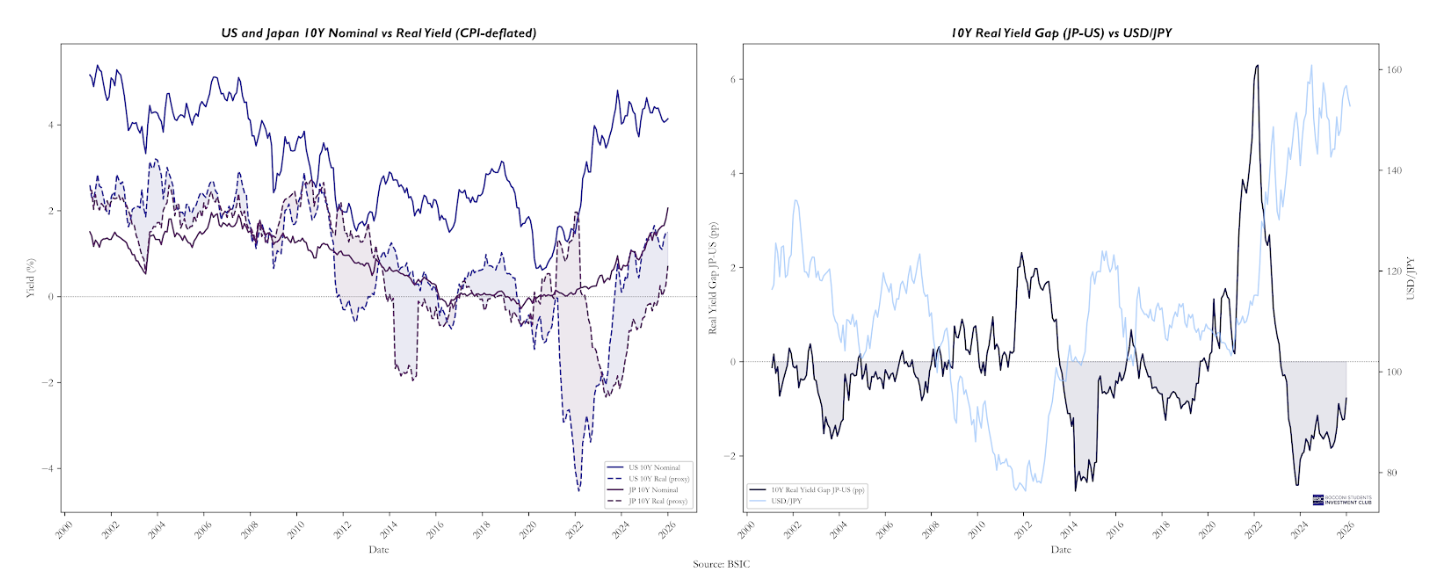

The real yield gap is not confined to the short end of the curve. Looking at 10-year government bond yields deflated by CPI inflation, the same dynamic holds. The 10-year maturity reflects longer-term market expectations and is therefore the rate that drives long-horizon capital allocation decisions by institutional investors, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds. As shown in the chart below, Japan’s 10-year real yield turned sharply negative from 2022 onward as CPI inflation rose faster than the BoJ allowed nominal JGB yields to move, a direct consequence of YCC constraining the long end while prices accelerated. Simultaneously, US 10-year real yields surged above 2%, as the Fed’s aggressive tightening cycle outpaced the inflation peak. The second graph makes the FX bridge explicit: periods where the real yield gap widens in favour of the US correspond closely to episodes of yen depreciation, reinforcing that the exchange rate is responding to real, not nominal, rate differentials.

The real yield gap is not confined to the short end of the curve. Looking at 10-year government bond yields deflated by CPI inflation, the same dynamic holds. The 10-year maturity reflects longer-term market expectations and is therefore the rate that drives long-horizon capital allocation decisions by institutional investors, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds. As shown in the chart below, Japan’s 10-year real yield turned sharply negative from 2022 onward as CPI inflation rose faster than the BoJ allowed nominal JGB yields to move, a direct consequence of YCC constraining the long end while prices accelerated. Simultaneously, US 10-year real yields surged above 2%, as the Fed’s aggressive tightening cycle outpaced the inflation peak. The second graph makes the FX bridge explicit: periods where the real yield gap widens in favour of the US correspond closely to episodes of yen depreciation, reinforcing that the exchange rate is responding to real, not nominal, rate differentials.

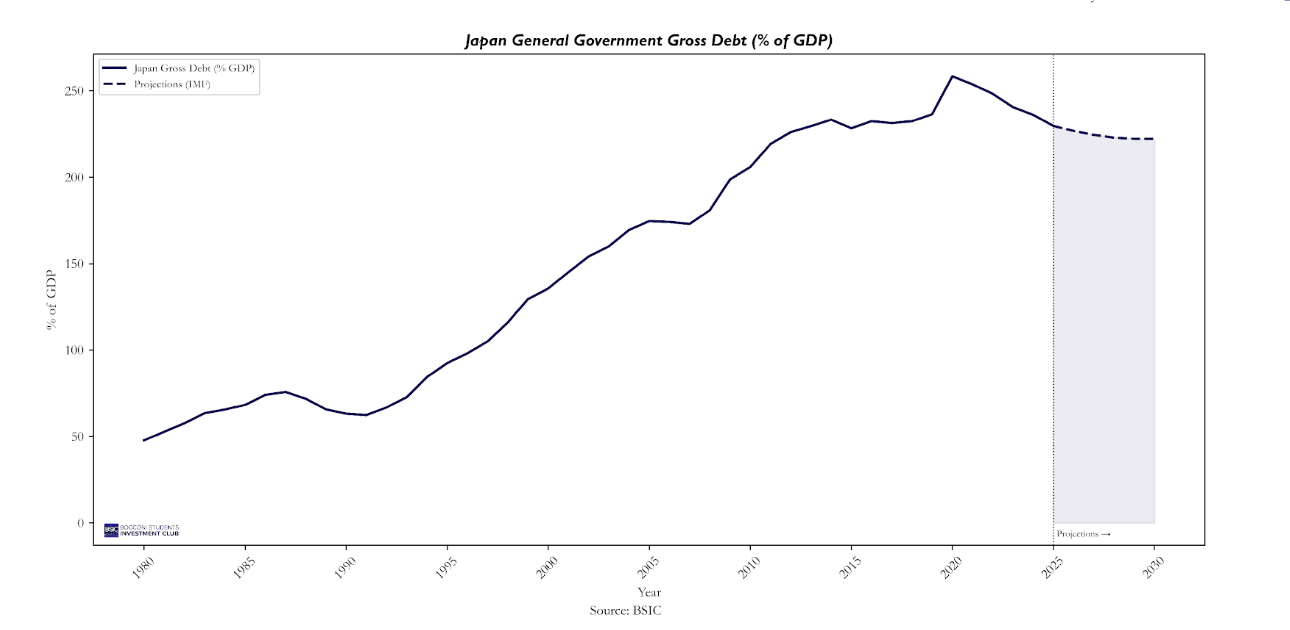

Fiscal uncertainty is a second element keeping the yen weak; markets are likely pricing a “fiscal premium” into Japanese assets. The point is to understand whether the new Japanese political cycle implies more deficit spending without a credible financing plan, which would mean either (i) higher JGB supply, (ii) pressure on the BoJ to stay accommodative, or (iii) some mix that ultimately discourages yen demand.

Japan is already starting from a heavy debt load, around 227% of GDP (projected in 2026), so even a modest shift in perceived discipline can move risk premia. That’s why it is important to focus on PM Sanae Takaichi’s post-election stance of Wednesday, 18 February. She emphasized her government’s first order of business is passing the FY2026 budget at ¥122.3tn, about +6.3% vs FY2025. However, she also discussed her government’s broader priorities for the coming year, including “responsible fiscal expansion,” “fundamental strengthening of security policy,” and “strengthening the government’s intelligence operations,” as well as pursuing social security and tax reform through a national conference that will take up the question of a consumption tax cut on foodstuffs.

To achieve these, Takaichi, Finance Minister Katayama Satsuki, and other members of her government have suggested that it is not enough to just increase the government’s budget. She wants to change how Japan budgets, shifting to large general budgets instead of annual supplemental budgets and relying on long-term funds to support government priorities. Many members of her government have also repeatedly said that they want to change how the Japanese government pursues fiscal balance (aiming for balanced budgets over a multi-year cycle instead of in a single year), while downplaying the significance of Japan’s gross debt, and suggested that the Takaichi government’s policies will enable Japan to grow its way out of debt. This would also help limit the power of the Ministry of Finance (MOF), which the LDP has identified as perhaps the single greatest obstacle standing in the way of their vision for Japan.

To achieve these, Takaichi, Finance Minister Katayama Satsuki, and other members of her government have suggested that it is not enough to just increase the government’s budget. She wants to change how Japan budgets, shifting to large general budgets instead of annual supplemental budgets and relying on long-term funds to support government priorities. Many members of her government have also repeatedly said that they want to change how the Japanese government pursues fiscal balance (aiming for balanced budgets over a multi-year cycle instead of in a single year), while downplaying the significance of Japan’s gross debt, and suggested that the Takaichi government’s policies will enable Japan to grow its way out of debt. This would also help limit the power of the Ministry of Finance (MOF), which the LDP has identified as perhaps the single greatest obstacle standing in the way of their vision for Japan.

There is no doubt that Takaichi is serious about increasing fiscal spending; the only doubt is on the consumption tax cut, which has been heavily criticised by the IMF. Indeed, Takaichi herself believes in the necessity of fiscal expansion. In her 2021 campaign book she says that her idea is to pick up where Abenomics left off: flexible fiscal stimulus to support large-scale investment in growth. “Until the two-percent inflation target is achieved,” she writes, “the ‘primary balance’ rules should be temporarily suspended to prioritize fiscal stimulus aimed at ‘bold crisis management and growth investment’.”

Growth and Structural Problems

The third topic to consider is growth expectations. Takaichi and other members of the LDP argue that the new fiscal plan, along with the stimulus measures that will follow, can be sustained primarily through higher economic growth. However, Japan faces structural challenges that cannot be overlooked and markets still expect Japan to remain a low-growth, low-real-yield economy that won’t “pay” you to hold yen for long.

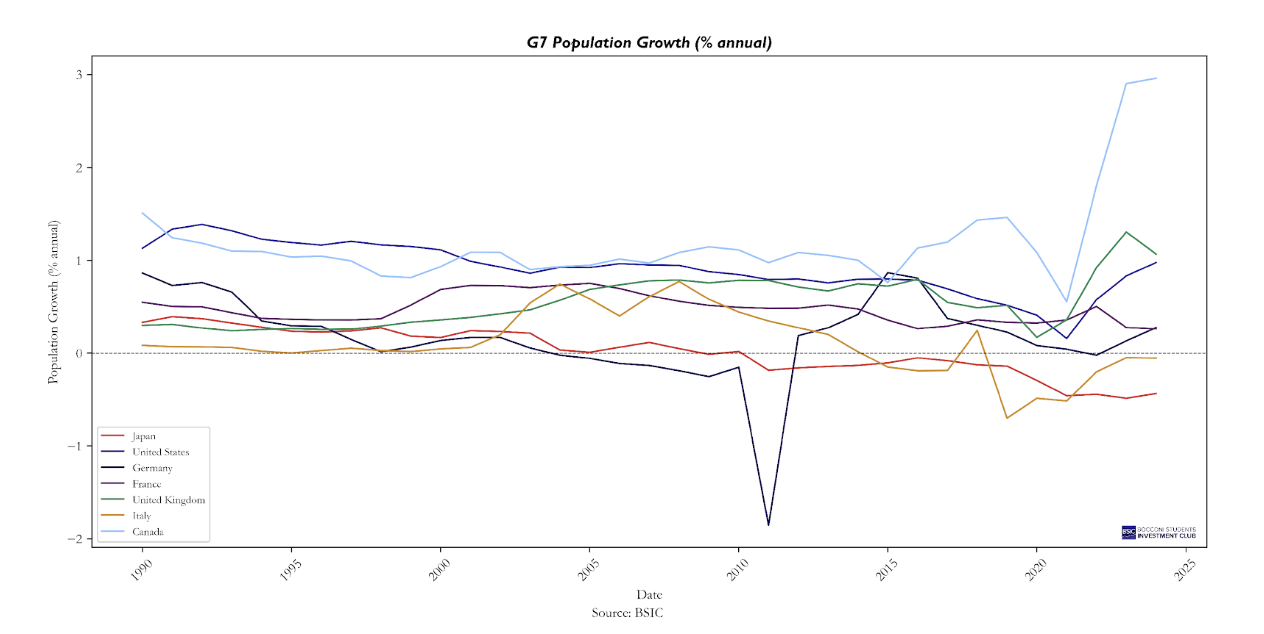

The first structural problem is demographic. The country’s total fertility rate reached a low of 1.26 in 2022 and has remained below the replacement level for nearly fifty years. Under current fertility, immigration, and employment parameters, Japan’s population falls from 125 million today to roughly 96 million by 2060 and below 70 million by 2100, a contraction of 45%. The labour force shrinks by more than half over that period. The fiscal pressure this generates is already visible: health, long-term care, and pension expenditure is projected to rise by ¥17tn, approximately 2.7% of projected 2025 GDP, between fiscal year 2025 and 2040 alone. Government spending on the elderly already exceeds spending on children and families by more than four to one, a structural bias in public expenditure that crowds out productive investment.

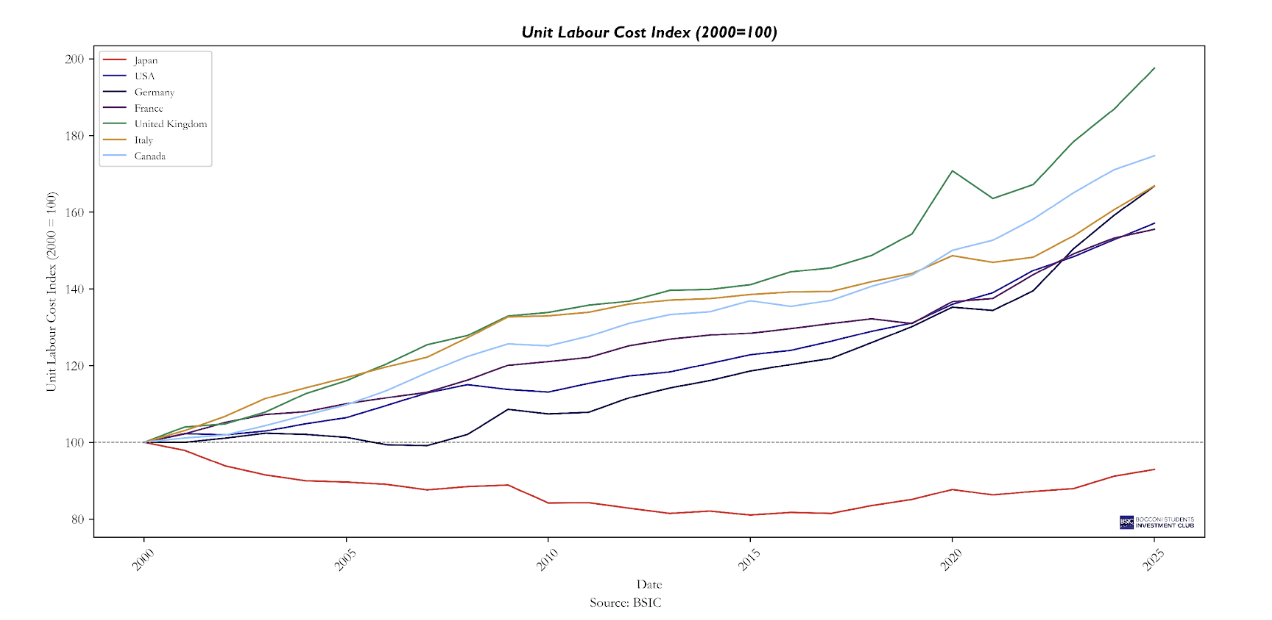

The second issue is productivity. Output per hour worked in Japan was 44% below the average of the top half of the OECD countries in 2021. Despite this, Japan also has world-class automation capacity; robot density in manufacturing was the 3rd highest globally in 2020. The primary mechanism for this large gap is labour market dualism: the rigid separation between “regular” workers, who enjoy near-absolute employment protection, seniority-based wages that rise automatically with tenure, and access to firm-specific training, and “non-regular” workers, who are cheap and flexible but receive low wages, minimal training and no meaningful job security. Non-regular workers now constitute roughly a third of the overall workforce. Given that wages for non-regular workers do not rise with experience or age, firms have no incentive to invest in their human capital and workers have no incentive to acquire firm-specific skills. The seniority wage system also amplifies the issue by overpaying older workers relative to their marginal contribution, discouraging mid-career job mobility and creating the structural inevitability of mandatory retirement, since firms must eventually terminate the automatic wage escalation of regular employees or face excessive costs. The result is that, in 2022, 94% of Japanese firms maintained a mandatory retirement age, and 70% set it at 60, in a country where healthy life expectancy at age 60 is an additional 20 years. The chart below captures this dynamic directly: Japan’s Unit Labour Cost Index has fallen to around 85 (2000=100) while every other G7 economy saw costs rise 30-90% over the same period, reflecting 25 years of productivity gains never passed through to wages.

The second issue is productivity. Output per hour worked in Japan was 44% below the average of the top half of the OECD countries in 2021. Despite this, Japan also has world-class automation capacity; robot density in manufacturing was the 3rd highest globally in 2020. The primary mechanism for this large gap is labour market dualism: the rigid separation between “regular” workers, who enjoy near-absolute employment protection, seniority-based wages that rise automatically with tenure, and access to firm-specific training, and “non-regular” workers, who are cheap and flexible but receive low wages, minimal training and no meaningful job security. Non-regular workers now constitute roughly a third of the overall workforce. Given that wages for non-regular workers do not rise with experience or age, firms have no incentive to invest in their human capital and workers have no incentive to acquire firm-specific skills. The seniority wage system also amplifies the issue by overpaying older workers relative to their marginal contribution, discouraging mid-career job mobility and creating the structural inevitability of mandatory retirement, since firms must eventually terminate the automatic wage escalation of regular employees or face excessive costs. The result is that, in 2022, 94% of Japanese firms maintained a mandatory retirement age, and 70% set it at 60, in a country where healthy life expectancy at age 60 is an additional 20 years. The chart below captures this dynamic directly: Japan’s Unit Labour Cost Index has fallen to around 85 (2000=100) while every other G7 economy saw costs rise 30-90% over the same period, reflecting 25 years of productivity gains never passed through to wages.

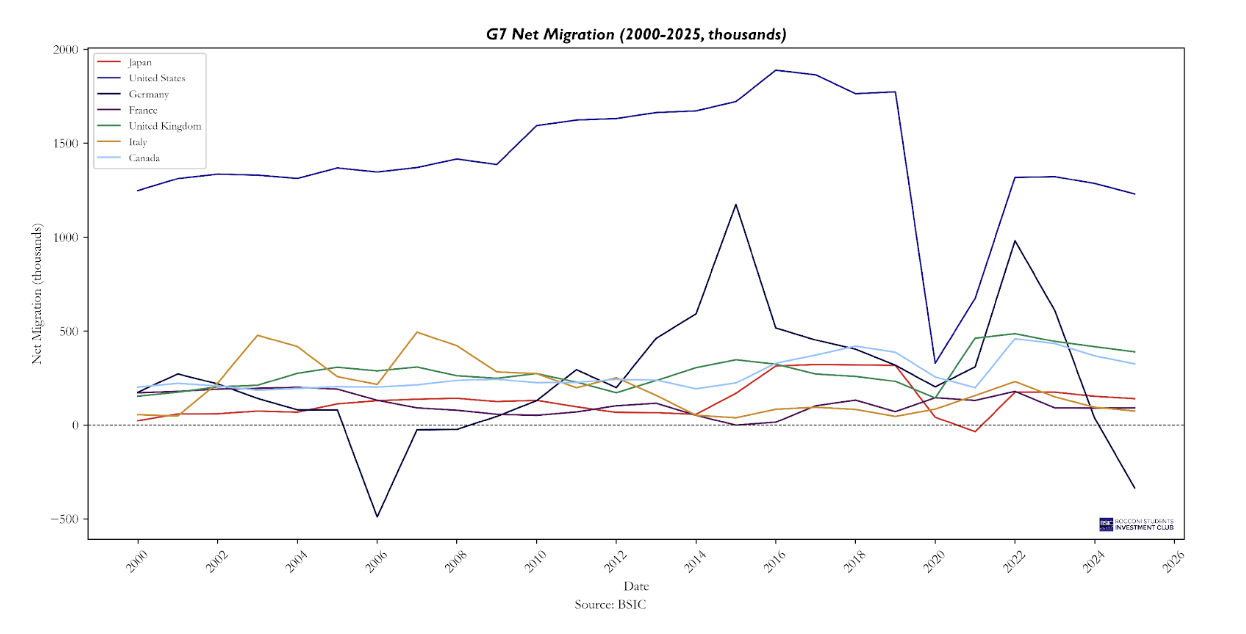

The third element is immigration. In recent years, the demographic situation has been so dire that the government has effectively had no choice but to accept more immigrants. Japan’s foreign-worker population has roughly quadrupled since 2007 to more than 2 million, a remarkable shift given its long history of minimal immigration. In addition, Japan’s pragmatic and incremental approach, favouring work-tied, often temporary entry over permanence and humanitarianism, likely helped minimise backlash and build tolerance for higher inflows. However, there is now a nascent anti-immigration trend, similar to those emerging across Europe and the USA. The problem is that, while in other countries the demographic trend is worsening, it is not as dire as in Japan. The barriers in Japan are often higher than elsewhere. Naturalisation is rare even for long-term residents, language training is underfunded, and the housing market is complex to navigate for foreigners. Indeed, even today foreigners in Japan make up just 2.3% of the population, among the lowest shares in the OECD. The baseline requirement for permanent residency is 10 continuous years, compared to 5 or fewer in most European countries and immediate residency for skilled migrants in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. Japan’s wages for migrant workers are already 26% below those of native-born workers, and projections estimate that Japan will cease to be economically attractive to workers from Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand (which together supply more than half its foreign labour) by 2032, as their own domestic wages rise.

The third element is immigration. In recent years, the demographic situation has been so dire that the government has effectively had no choice but to accept more immigrants. Japan’s foreign-worker population has roughly quadrupled since 2007 to more than 2 million, a remarkable shift given its long history of minimal immigration. In addition, Japan’s pragmatic and incremental approach, favouring work-tied, often temporary entry over permanence and humanitarianism, likely helped minimise backlash and build tolerance for higher inflows. However, there is now a nascent anti-immigration trend, similar to those emerging across Europe and the USA. The problem is that, while in other countries the demographic trend is worsening, it is not as dire as in Japan. The barriers in Japan are often higher than elsewhere. Naturalisation is rare even for long-term residents, language training is underfunded, and the housing market is complex to navigate for foreigners. Indeed, even today foreigners in Japan make up just 2.3% of the population, among the lowest shares in the OECD. The baseline requirement for permanent residency is 10 continuous years, compared to 5 or fewer in most European countries and immediate residency for skilled migrants in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. Japan’s wages for migrant workers are already 26% below those of native-born workers, and projections estimate that Japan will cease to be economically attractive to workers from Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand (which together supply more than half its foreign labour) by 2032, as their own domestic wages rise.

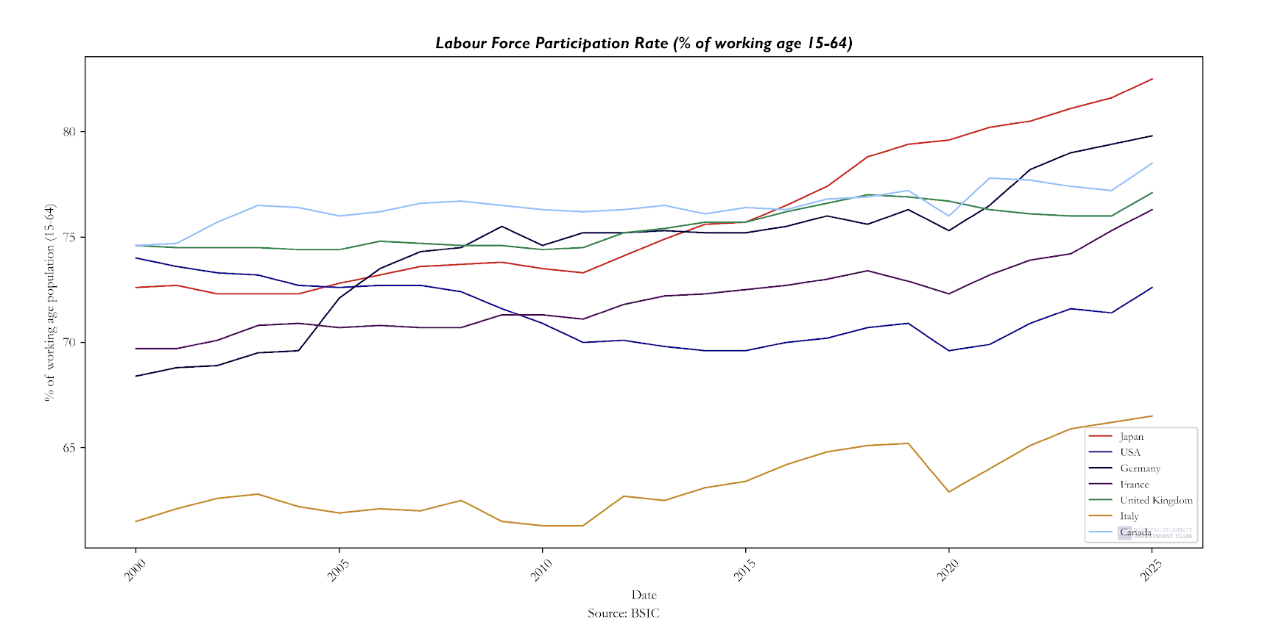

The fourth element to consider is female labour force participation, which could really help Japan’s growth. The female employment rate rose from 60.7% in 2012 to 72.4% in 2022, now above the OECD average, driven by expanded childcare capacity. However, the quality of this employment tells a different story. Of female employees, 55% are in non-regular positions, which implies, as noted above, lower wages and the absence of bonuses, which are 20% of annual compensation for regular workers. In addition, women hold just 13.2% of management positions.

The fourth element to consider is female labour force participation, which could really help Japan’s growth. The female employment rate rose from 60.7% in 2012 to 72.4% in 2022, now above the OECD average, driven by expanded childcare capacity. However, the quality of this employment tells a different story. Of female employees, 55% are in non-regular positions, which implies, as noted above, lower wages and the absence of bonuses, which are 20% of annual compensation for regular workers. In addition, women hold just 13.2% of management positions.

Future Dynamics in Rates and FX markets

Future Dynamics in Rates and FX markets

As I have explained above, the current weakness of the yen cannot be explained by the yield story alone; fiscal expectations and Japan’s structural issues are equally relevant. However, it is worth looking more carefully at what reasonable expectations for the future path of policy rates in both countries imply for the exchange rate.

In the US, federal funds futures are currently pricing around two cuts in 2026, a view consistent with Polymarket odds which, over the past years, have shown a reasonable ability to anticipate Fed decisions. This would bring the US policy rate to 3.00-3.25% by end of year. In Japan, the picture is less clear, but it is reasonable to expect the BoJ to continue its gradual normalisation, hiking rates to around 1.25-1.50% over the same horizon. On inflation, both central banks are targeting 2%. In the US, core CPI is currently running above target but is broadly expected to trend down toward 2% through 2026. In Japan, the metric has been more volatile, but a value close to 2% by end of 2026 is equally plausible given the current trajectory.

Under these assumptions, the nominal rate differential could compress to around 175bp from the current 300bp. The real differential could narrow by a similar magnitude if inflation converges in both countries toward 2%, or compress even further if US inflation remains above Japan’s.

Overall, the differential would stay negative, but its continuous drift toward zero could begin attracting Japanese investors back to domestic assets, given the improving returns available at home. This possibility has become highly relevant in current market discussions. It must be remembered that at end of 2025 Japanese investors held 18% of the US Treasury market, making them the largest foreign creditors. The steady rise in Japanese government bond yields is steadily eroding the relative attractiveness of holding US Treasuries. As I explained above, it is not straightforward that rising rates will trigger massive capital movements (nominal rates alone do not tell the whole story, and real rates and broader market conditions must also be considered), but a narrowing spread nonetheless reduces the attractiveness of staying abroad.

Another fundamental dynamic is the hedging of yen exposure. Through most of the 2000s and 2010s, Japanese life insurers and pension funds were largely unhedged on their foreign bond positions. The reasoning was straightforward: hedging costs (the cross-currency basis swap, which roughly equals the short-term rate differential) were expensive relative to the yield pickup. If you are buying a US Treasury at 2% and paying 1.5-2% to hedge the dollar exposure back to yen, the net return is barely above a JGB. Many institutions decided the currency risk was worth taking unhedged, particularly since the yen was relatively stable for extended periods. When the dollar surged and USDJPY moved from 115 to 160, unhedged foreign bond holders made enormous currency gains, which perversely made them less likely to repatriate, since they were sitting on large unrealised FX profits that would trigger a taxable gain on repatriation. Now, however, these dynamics are moving in the opposite direction. The yen looks undervalued on many metrics, and Japanese insurers and pension funds must start factoring in hedging costs, making domestic investment considerably more attractive. Combined with rising yields at home, it becomes clear why many have been calling for potentially large moves in bond and FX markets.

The risk that Japanese investors choose to come home is not trivial. For example, the Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF), as of mid-2025, allocates around 50% of its assets to international stocks and bonds in roughly equal measure. The GPIF manages approximately $1.8tn, making it the second largest pension fund in the world, behind only Norway’s sovereign wealth fund. Any repatriation of investments would clearly not happen suddenly but gradually: maturing bonds reinvested domestically and portfolios tilting back toward home markets. The cumulative effect on international equity and bond markets could nonetheless be significant.

An additional catalyst worth watching is Japan’s large and rising debt stock itself. With the Bank of Japan no longer absorbing issuance as it once did, someone will have to buy those bonds. It becomes increasingly plausible that, in order to encourage Japanese institutions to invest at home, policymakers will deploy quiet, incremental incentives designed to pull Japanese capital back onshore and help manage rising debt servicing costs.

With this article, we have tried to show how the yen’s weakness is justified by fundamental factors that cannot be ignored. First, real rates still favour the dollar and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Second, markets have yet to see how the new political policies Takaichi’s party is planning to implement will truly impact Japan; while it is clear that she both desires and is able to implement the fiscal stimulus she has planned, other policies remain unconfirmed, most notably the consumption tax cut. Third, the growth outlook remains genuinely uncertain: while the LDP’s policies will stimulate the economy, there are doubts about the scale of spending required, and there are fundamental issues with the Japanese economy linked to productivity and demographics that appear, for now, too deeply structural to be resolved quickly, particularly given Takaichi’s party’s resistance to meaningful immigration reform.

Despite this, recent trends in policy and market rates are raising doubts among large Japanese asset holders about the merits of holding foreign assets, particularly where FX exposure must be hedged. These shifting dynamics could prompt the massive pension and insurance funds to move capital, even gradually, toward newly attractive Japanese holdings, which could prove significantly disruptive for markets in countries like the US.

References

- Jones, R. S. (2024). Addressing demographic headwinds in Japan: A long-term perspective (OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1792). OECD Publishing.

- International Monetary Fund. (2024). Japan: 2024 Article IV consultation. IMF Country Report.

- Hofmann, B., Shim, I., & Shin, H. S. (2020). Emerging market economy exchange rates and local currency bond markets (BIS Working Papers No. XXX). Bank for International Settlements.

0 Comments