Introduction: Infrastructure as an Asset Class

Infrastructure investing involves allocating capital towards large-scale physical and organisational structures that provide essential services, such as transportation, energy, water, and telecommunications. These assets are critical for the functioning and growth of economies, often offering long-term, stable returns for investors. Infrastructure investments can be made through direct ownership, listed infrastructure funds, or public-private partnerships (PPPs). The asset class is known for its inflation-linked income streams and typically lower volatility than other investments, making it highly attractive to institutional investors, including pension funds and sovereign wealth funds.

Types of Infrastructure Assets

Infrastructure encompasses a wide variety of assets. Some key examples include:

Data Centres: Facilities housing servers and data storage systems that power the internet, cloud computing, and telecommunications.

Toll Roads: Privately owned highways or bridges where users pay fees for access.

Airports: Essential for global transportation and commerce, with revenue derived from airlines and passengers.

Solar Farms and Wind Farms: Renewable energy assets generating electricity through solar panels and wind turbines, vital in the transition to cleaner energy sources.

Energy Pipelines: Networks transporting oil, gas, and other energy resources essential for energy distribution.

Healthcare Facilities: Hospitals, clinics, and medical centres providing essential health services, which have become increasingly important in ensuring public health and welfare.

Each of these assets has unique characteristics and risk-return profiles; however, they share common traits: they tend to have high upfront costs, long operational lifespans and offer steady, predictable income once operational.

Pure-play Infrastructure Investors

Pure-play infrastructure investors are firms that exclusively or primarily focus on investing in infrastructure assets. These investors typically allocate significant portions of their capital to sectors such as transportation, energy, utilities, and communication, aiming for stable, long-term returns. Some of the most significant pure-play infrastructure investors globally are:

Brookfield Asset Management [NYSE: BN]: A Canadian-based company with approximately $1tn in assets under management (AUM). Brookfield is a global alternative asset manager focused on investing in real estate, infrastructure, renewable power, and private equity.

Macquarie Asset Management [ASX: MQG]: Headquartered in Sydney, Macquarie Asset Management manages $633.6bn in AUM. It is a global leader in infrastructure investment, offering a range of services across equity, debt, and advisory.

EQT [XSTO: EQT]: Based in Stockholm, EQT manages $245.08bn in AUM. The firm focuses on private equity, real estate, and infrastructure investments, and is strongly commited to sustainable growth.

Global Infrastructure Partners: Located in New York, Global Infrastructure Partners manages approximately $170 bn in AUM. The firm invests in infrastructure assets across various sectors, including energy, transportation, and water.

DigitalBridge: Based in Boca Raton, DigitalBridge manages $84bn in AUM. It is a leading investment firm focused on digital infrastructure, including data centres, cell towers, and fibre networks.

IFM Investors: Headquartered in Melbourne, IFM Investors manages $73.6bn in AUM. It is a global fund manager owned by Australia’s industry superannuation funds, focusing on infrastructure, debt investments, and listed equities.

Stonepeak: Located in New York, Stonepeak manages approximately $70bn in AUM. The firm focuses on infrastructure investments in the energy, utilities, and telecommunications sectors.

Antin Infrastructure Partners: Based in Paris, Antin Infrastructure Partners manages approximately $30bn in AUM. The firm specializes in investing in infrastructure assets across Europe and North America, focussing on the energy and transportation sectors.

Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners: Headquartered in Copenhagen, Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners manages $27bn in AUM. The firm focuses on investments in renewable energy infrastructure, including offshore and onshore wind farms and solar power projects.

Construction Companies

Construction companies are crucial partners in infrastructure investing, as they are responsible for turning investment capital into tangible projects. These companies deploy their expertise to build and maintain large-scale infrastructure assets, so the success of these projects relies heavily on their ability to manage costs, timelines, and risks during construction.

Many infrastructure projects, especially in project finance (discussed later), use Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) contracts. In such contracts, the construction firm assumes the risk for all project operations from the design phase to the construction phase, and for delivering a project on time and on budget.

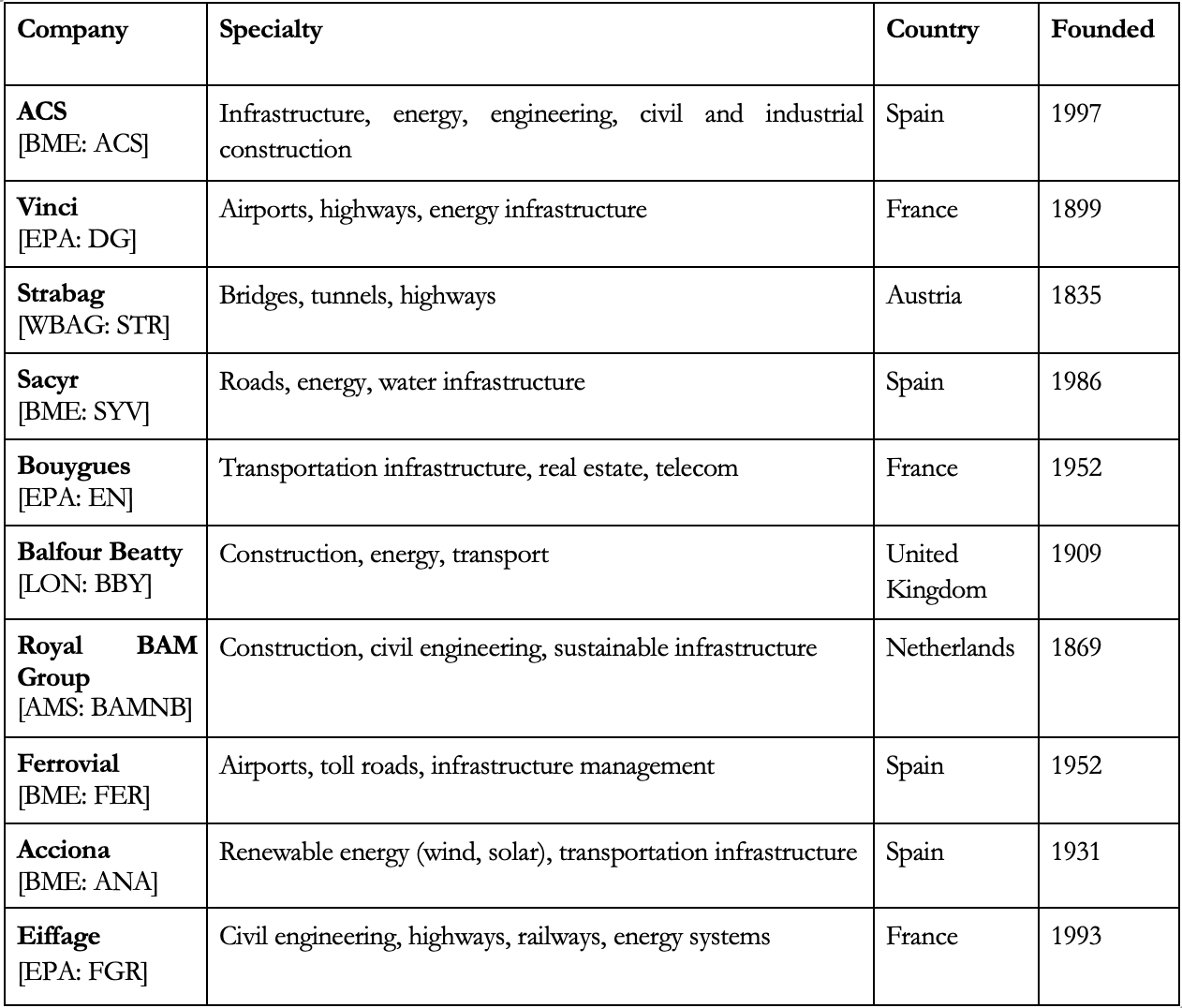

As such, most infrastructure development deals are made on the merits of long-term partnerships and the reputations of the construction company, with the most prominent players in Europe (sorted by revenue for 2023) being the following:

Source: Blackridge Research and Consulting, BSIC

Infrastructure as an Asset Class: Size and Importance

Infrastructure is an asset class within broader real assets, a space encompassing tangible assets or resources, including real estate, land and natural resources, and commodities. Historically, infrastructure has been defined as the assets needed to operate a society or move people and physical goods, such as toll roads, bridges, airports, waterways and utilities. But, over the past decade, this asset class has grown drastically beyond these categories to include more modern infrastructure that reflects broader transformations within our economy, such as the transition to a digital world and the global push towards sustainable and green infrastructure as governments strive to meet climate goals.

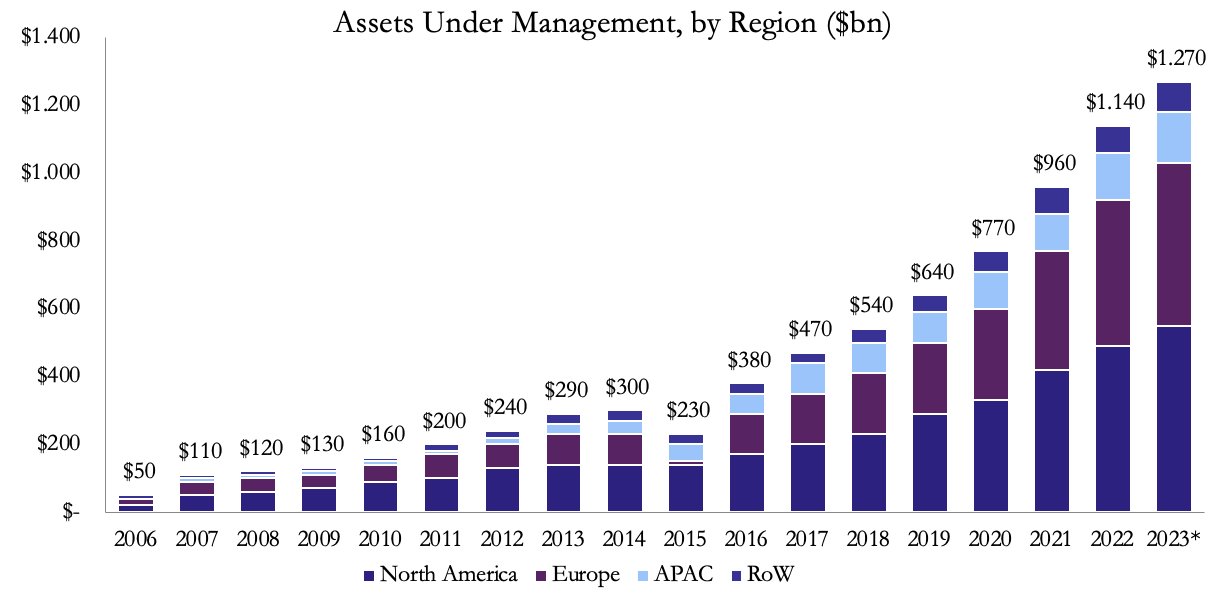

As the range of investable infrastructure subcategories grows, government stimulus and private capital entering the asset class indicate strong support for ongoing investment. Private infrastructure assets under management (AUM) have surpassed $1tn and are expected to increase to more than $3.5tn by 2035, driven by growing demand from investors for defensive, stable asset classes.

For most of the past decade, Europe has been the world’s largest private capital infrastructure market, averaging 34% of transactions by volume, roughly on par with North America (about a third each of the world market). Despite this, the investment patterns across the continents vary significantly.

Europe, at the forefront of the transition to net zero, presents exceptional investment opportunities in clean energy and green infrastructure. As a result, renewable energy and digital infrastructure account for just over 50% of all transactions in Europe, a notably higher proportion compared to the rest of the world. The EU’s recent investment of over €7bn in 134 transport projects under the Connecting Europe Facility, with 83% of the funds dedicated to climate-focused initiatives like modernising railways, waterways, and maritime routes, underscores its strong commitment to bolstering climate objectives, which are a cornerstone of its broader infrastructure development strategy.

In contrast, North America sees significantly lower investment in digital infrastructure and a stronger focus on the energy sector, which signals a favourable attitude towards more “traditional” sectors like oil and gas. Recent policy updates in the United States aim to support private equity investment in infrastructure. In 2021, Congress passed legislation to deliver $1.2tn of government funding to infrastructure assets through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Many political and financial analysts believe the bill will pave a long runway of infrastructure growth and innovation, creating a real opportunity for private investors to invest independently or partner with government agencies. More recently, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provided an unprecedented financial commitment by the U.S. government to global decarbonization, with around $369bn in funding for energy security and climate change programs, which may shift the predominant focus away from energy and closer to renewables.

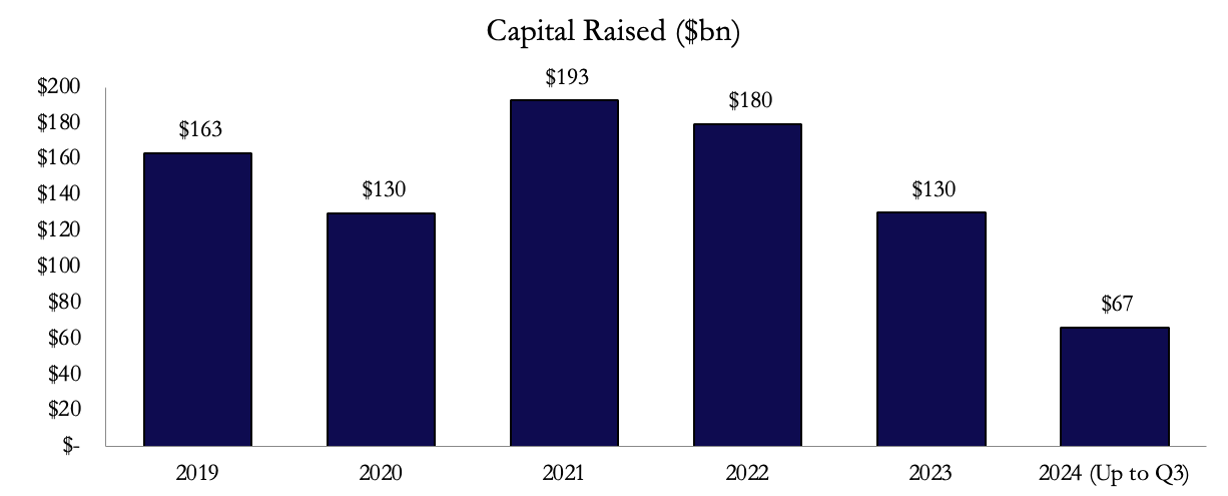

Infrastructure funds slumped in 2023, with a 27.5% drop year-over-year. The 2024 figures are more optimistic, with $66.5bn raised from Q1 to Q3, partly due to interest cuts and strong public market performance compared to the past year. This momentum could persist in Q4 2024, with at least 117 funds actively engaged in raising over $196bn, according to Infralogic Fund Market Tracker. However, all it will take to derail this year’s performance is a lack of large fund closes in the last quarter.

Source: Infrastructure Investor, BSIC

Why Invest in Infrastructure?

Infrastructure provides investors 4 key features: income, diversification, inflation protection and risk management. Infrastructure projects such as toll roads, wind turbines and seaports provide a consistent income through fee for usage. Some infrastructure projects may not service this use as they might have unclear or inconsistent revenue streams such as schools. Investing in projects in different sectors and different countries may also hedge against economic downturn. This is due to how infrastructure has a low correlation with other asset classes. Therefore, investing in the construction of gas storage may hedge against the risk of an investment in the tech sector. Investing in infrastructure may also hedge against inflation due to its underlying induced demand, inherent value and ability to counteract increasing operating costs. Infrastructure is key to everyday life. While consumers spend less on retail or technology in an inflationary period, they still utilize most infrastructure at similar rates providing consistent demand even with price increases. In addition, infrastructure projects are uniquely positioned to remain profitable despite inflation due to the ease of increasing prices. An oil pipeline may simply increase its products price (oil barrels) to counteract its increasing operating expenses protecting the income of the investment against inflation. Infrastructure also has a lower beta (market sensitivity) than other equities. Therefore, its more resilient to market downturn. This lower beta is derived from the fundamental need of infrastructure which makes it an effective hedge against market volatility and a stable return on risk adjusted capital.

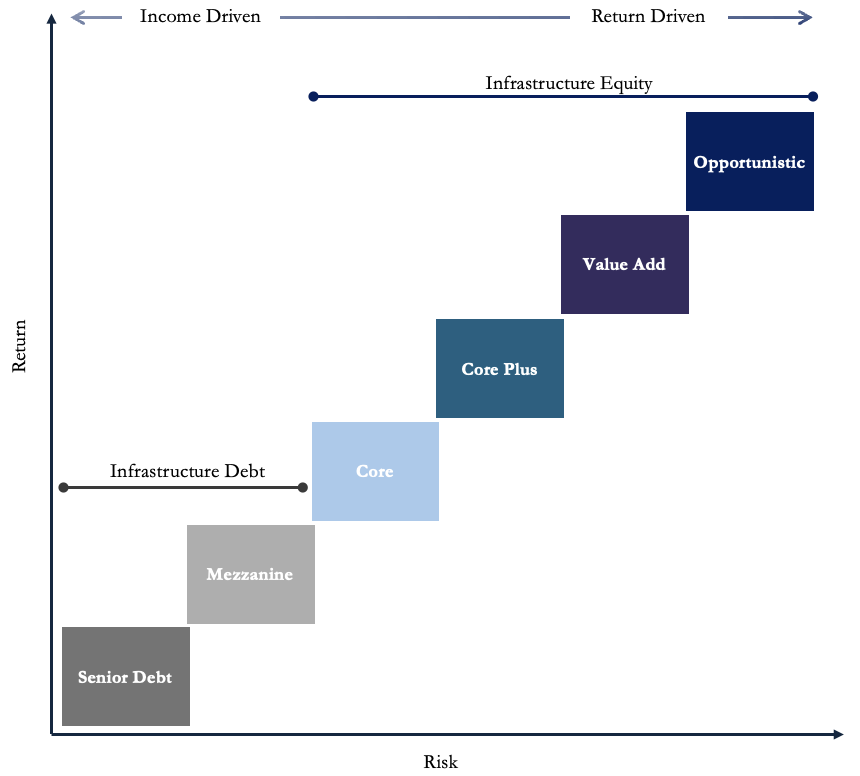

Infrastructure equities are divided in various asset classes (strategies) based on risk and yield. This variation is reliant on various factors which would affect the completion of the infrastructure project. A key factor is the phase of investment window such as greenfield, brownfield and secondary stage. Greenfield projects still need to be planned and built. Investors will foot the cost of this initial phase where future values such as usage or final costs are not assured. Investors also pay for maintenance. This relatively high risk permits for larger yields on the investment. Brownfield projects need renovations and/or expansion. They tend to be partially operational with an income. Secondary stage projects have stable cashflows. Investment in this phase is to grow and develop the asset (may restart greenfield/brownfield cycle).

Infrastructure investors tend to invest with either core, core plus or value add investment strategies. A core infrastructure strategy invests in projects which provide stable income and have no operational risk such as toll roads in major markets. They are typically secondary stage assets. They tend to provide an essential public need, have protected market positioning and generate predictable cashflows/return on equity. They are usually found in developed countries. They have stable capital structures and have induced demand/contracted revenue from government involvement (i.e. rail networks). The rationale of a core strategy is to invest in assets with a consistent income and a low risk of failure due to the safeguards promoting success. A core plus strategy invests in projects that are in undeveloped markets but have low construction risk such as non-regulated airports in industrial cities. They are typically either secondary stage or a brownfield developed market. Although being more exposed to market volatility many projects feature risk reducing mechanisms such as long-term contracts, high barriers of entry for competitors and regulatory price support. The purpose of a core plus strategy is to provide consistent income with higher risks and higher yield than core. A value-add strategy aims to enhance a preexisting asset such as an existing rail network upgraded to be high speed. They are typically greenfield or brownfield. These projects may seek to increase the underlying value or improve upon preexisting contracts. The motive of a value-add strategy is that an improvement in the asset will increase demand and thus also increase income and appreciation. The risk profile is moderate to high due to lack of pricing power.

Specialty infrastructure investment strategies seek to maximize certain key features of this tranche such as infrastructure debt and opportunistic. Infrastructure debt involves loaning money to infrastructure owners for capital expenses, to refinance debt or acquisitions. For instance, loaning to money to a fiber cable project follows an infrastructure debt strategy. The risk exposure may vary from the type of debt provided such as mezzanine or senior loans. However, infrastructure debt tends to have the least exposure as most projects are financed through senior debt and have simple capital structures. The aim of an infrastructure debt strategy to provide steady returns (interest) at a low risk. An opportunistic strategy on the other hand invests in infrastructure which needs to be either majorly developed or entirely constructed such as luxury real estate in a developing country. They tend to be projects which are extremely sensitive to shifts in demand and have non contracted revenue. This leads them to be the riskiest infrastructure asset class. The intention behind an opportunistic strategy is less to develop stable cash flows but rather to profit off the capital growth of the underlying asset, aiming to create quasi-PE style returns.

Source: Brookfield, BSIC

Current State of the Infrastructure Investments Arena

Infrastructure is essential for consumers and industry to flourish. Functioning transport networks, industrial ports and bridges all serve to facilitate the exchange of goods and services. Hospitals, Schools and Housing help educate and maintain a healthy population. Globally many countries are now facing severe deficits in infrastructure due to years of limited spending and growing demand. This has influenced recent policy decisions such as Bidens Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (2021) which committed $1.2tn in the funding of various projects such as roads, ports and public rail. Regions such as Africa and Southeast Asia (excluding Singapore) have been plagued by infrastructure issues due to their quick growth. Issues such as a lack of highways, inefficient ports and lacking digital infrastructure plague countries such as India and Mauritania. Western Europe and the US have crumbling roads and bridges which are hazards for industry. These regions will have to begin to commit to larger infrastructure spending. Uniquely, the East Asian region has gone through an infrastructure renaissance. Through massive government projects and the emergence of a strong private sector spurred by privatization, countries such as South Korea, Japan and China have developed a strong infrastructural basis from which industry may build off. This was derived from the massive commitment made by this region with an average of 5.0%, 8.5% and 4.3% GDP expenditure by Japan, PRC and South Korea infrastructure respectively from 1998 to 2018. These countries will have to continue prioritizing infrastructure investment to maintain their competitive advantage and grow.

Following the global financial crisis, Infrastructure was viewed as less lucrative than other assets. Throughout the 2010s this asset class quickly lost that reputation ballooning from $130bn AuM in 2009 to $1.27tn AuM in 2023. The money pouring into infrastructure deals also grew from $16.4bn in 2009 to a peak of $173.7bn in 2022.

Source: Preqin Pro, Financial Times, BSIC (*2023: January to June)

Infrastructure funds have been growing rapidly and are forecast to hit $2.5tn by 2027, due to the numerous structural trends that are highly supportive for the asset class. These structural trends can be split into two sections; capital scarcity and increased demand for funding. Capital scarcity has largely been driven by huge government deficits around the world and their inability or unwillingness to provide capital and funding for infrastructure projects. Therefore, the provision of funding infrastructure investment needs to be achieved through public-private partnerships. Capital scarcity may also be observed in the private sector, where many companies need to refinance maturities of existing funding arrangements that were struck initially in a much lower interest rate environment, and they need to raise capital just to hold onto their embedded assets. Increased demand for funding new infrastructure projects are accelerating. Brookfield estimate $200tn of Global infrastructure investment is needed in the next 30 years, which they claim is drive by three converging megatrends: Digitalization, Decarbonization and Deglobalization.

Digitalisation, where there is a demand for data which needs to be transferred, processed, and stored, in turn, driving demand for fibre networks, towers, and data storage centres all of which requires investment in infrastructure. The rapid rise of AI technology will further accelerate these demands.

Decarbonisation is driving demand for infrastructure investments with many governments setting goals of net zero emissions by 2050. For the first time, costs of renewables, including solar and wind is cheaper than oil, gas, and coal. Aside from the obvious required investment in wind turbines, solar panels and in some cases mini nuclear reactors, all this energy needs to be transmitted and delivered which requires infrastructure investments. According to Bloomberg Energy Transition Investment Trends 2024 research, “to align with the Paris-aligned Net Zero Scenario, global energy transition investment needs to average $4.84tn per year between 2024 and 2030”. This further highlights the huge demand for infrastructure funding.

Deglobalisation is a growing trend and requires infrastructure investments. For example, the US Inflation Reduction Act provides $370bn of financial incentives to ensure energy and climate security. Geopolitical events have pushed countries in Europe towards energy security and investment will be needed for the storage and transmission of natural gas. Geopolitical events with China are resulting in many US companies to re-onshore chip manufacturing capacity.

Dissecting the market outlook, investors should have relative optimism. The major trends shown described above of Digitalization, Decarbonization and Deglobalization coupled with decreased borrowing costs continue to fuel growth in this market. AuM are expected to increase to $3.5tn by 2035. Recent large investments include Microsoft’s [Nasdaq: MSFT] €4.3bn initiative to build AI infrastructure and cloud capacity in Italy. The European Union also gave €7bn of grants (split over 134 transport projects) to optimize cross-border rail connections, renovate 20 maritime ports, improve inland waterway infrastructures, simplify air traffic control and create safer areas for individuals and professionals.

Infrastructure Investing: A More Attractive Asset Class for Funds

Recently, large Generalist Asset Managers and PE funds have been acquiring Infrastructure Funds. These are two sets of Asset Managers at polar ends of the fund manager universe yet both groups are moving into infrastructure. The rationale behind this varies on the company, but in general it is to create a stream of steady earnings, which have less price fluctuations compared to other asset classes. Additionally, it is to diversify their portfolios and capture the high potential growth infrastructure assets are expected to undergo, due to digitalization and energy transformation movements, which require infrastructure to take place.

BlackRock Acquisition of Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP)

Founded in 1988, BlackRock [NYSE: BLK] is the largest asset manager in the world with approximately a $10tn AUM, with a market cap $139bn. On the 12th January 2024, BlackRock acquired GIP, a company investing in infrastructure which manages over $100bn, for $3bn cash and 12mn shares of BlackRock, valuing the deal at $12.5bn. Looking more closely at the deal structure, approximately 30% of the consideration (all in stock) was deferred and is expected to be issued in approximately five years, subject to the satisfaction of certain post-closing events. BlackRock stated it would fund the transaction through raising additional debt. Indeed, on 5th March it issued $2.5bn of three tranches of senior unsecured notes and stated it intended to use the proceeds for the GIP acquisition. Ultimately, the deal was completed on the 1st of October.

Primarily, this deal demonstrates BlackRock’s motive to further diversify and a move further into a long-term growth sector. According to Blackrock’s 2023 annual report, alternatives represents just 3% of long-term AUM, with various other public statements pointing out that pre-acquisition, BlackRock’s AUM in infrastructure was just $50bn (0.50% of AUM). Infrastructure has proved to be a resilient asset class through various market cycles, therefore, not only does infrastructure provide diversification to an underlying investors portfolio, but it also provides stability to a fund managers fee and therefore earnings, and ultimately their share price. Infrastructure has proved to have a low correlation to other asset classes and is less likely to fluctuate with speculative market movements. Additionally, BlackRock hopes to capitalise on the potential growth infrastructure offers.

The acquisition triples BlackRock’s AUM in infrastructure and the combined platform has become the second largest infrastructure AM in the world with approximately $170bn in AUM and expands BlackRock’s run rate revenues in private markets with approximately $750mn of run rate management fees. As a result of this deal, BlackRock are now in a position to provide infrastructure investment expertise to existing clients and are well positioned to capture the growth opportunities highlighted above that the sector is offering.

CVC buys Dutch infrastructure firm DIF Capital Partners

Established in 2005, CVC [AMS: CVC] is a private markets asset manager based in Jersey, focused on private equity, secondaries, credit, and infrastructure. With an AUM of €193bn, CVC completed its IPO in April 2024 with a valuation of about €14bn. It was announced on 5th September 2023 that CVC would acquire an initial 60% stake in DIF which has around a €16bn AUM, with the majority of funds being traditional infrastructure funds targeting low risk investments ranging from government concessions, utilities, and renewables. The deal states an additional 20% will be acquired at the start of 2027, with the final 20% being purchased in 2029. Further details of this deal can be found in CVC’s IPO document (page 345), with the funding of the deal summing to €400mn in cash, and the deal being finalised on 3rd July 2024.

For years, cheap financing and leveraging has made it easy for PE’s to buy companies, where they also heavily relied on rising equity markets to ensure a profitable exit. For obvious reasons, this environment which PE’s thrived in has changed, and acquiring DIF and increasing exposure to infrastructure gives access to an asset class with quite different dynamics. With longer duration, inflation-linked cash flows, and predictable returns they are easier to finance, with funds dedicated to infrastructure raising large pools of capital. “Expanding into infrastructure is a logical next step for us, given the long-term secular growth trends in infrastructure and its adjacency to our existing strategies,” CVC Chair Rolly van Rappard said in the statement. Ultimately it could be argued that the key driver for the acquisition was to diversify the business ahead of their IPO, as many equity investors may not assign a high valuation to unpredictable performance fees earned by traditional PE, and might prefer the stable and predictable revenue streams that infrastructure is able to offer.

General Atlantic acquisition of Actis

Established in 1980 to invest in high-growth businesses, General Atlantic has $83bn AUM (Feb 2024), and announced on the 16th January 2024 that they would be purchasing Actis, a UK based infrastructure fund. Actis is a leading global investor in sustainable infrastructure with an AUM of $12.5bn. The financial terms of the transaction were not publicly disclosed but according to a company press statement, Actis will “remain independent” over its funds and will continue to market its fund under its own branding. According to Bloomberg, “Actis will operate as General Atlantic’s Sustainable Infrastructure business alongside its existing strategies in Growth Equity, Credit, and Climate”. This deal was completed on 2nd October 2024.

Given there is little or no overlap, in neither cost bases nor markets, synergies are not a reason for this deal being executed. The rationale for this deal is strategic. General Atlantic chairperson and CEO Bill Ford stated in the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos that he saw a “multi-decade opportunity” in energy transition, adding the world needed more renewable energy to power itself. According to a media release by general Atlantic, the rationale is predominately due to the desire to “create a more diversified investing platform, bolstering General Atlantic and Actis as strategic long-term partners to both investors and management teams”, as well as to “deliver immediate scale and a broader set of investment solutions for investors”. Furthermore, according to General Atlantic, this deal will place the two firms in a position to open new opportunities in the energy and digitization transformation for investors. The focus on energy transition and digitization highlights the importance of two of the “mega trends” discussed above.

In summary these three deals highlight the attractiveness of infrastructure as an asset class to both traditional fund managers and PE fund managers. In an environment of higher interest rates, inflation, uncertainty, and market volatility infrastructure offers resilient, stable returns with diversification. The growth outlook for the sector is appealing with both demand for infrastructure funding from borrowers, support from regulators and demand from investors.

Project Finance: Common Financing Mechanism for Infrastructure Projects

Project finance is a specialised funding mechanism widely used in oil extraction, power generation, and infrastructure development. These sectors are well-suited to this structured financing technique due to their low technological risk, relatively predictable markets, and long-term contractual relationships, often with a small number of large buyers. In this model, financing is based on the project’s future cash flows rather than the sponsoring company’s balance sheet. Lenders are primarily repaid from the revenue generated by the project itself, with the project’s assets acting as collateral.

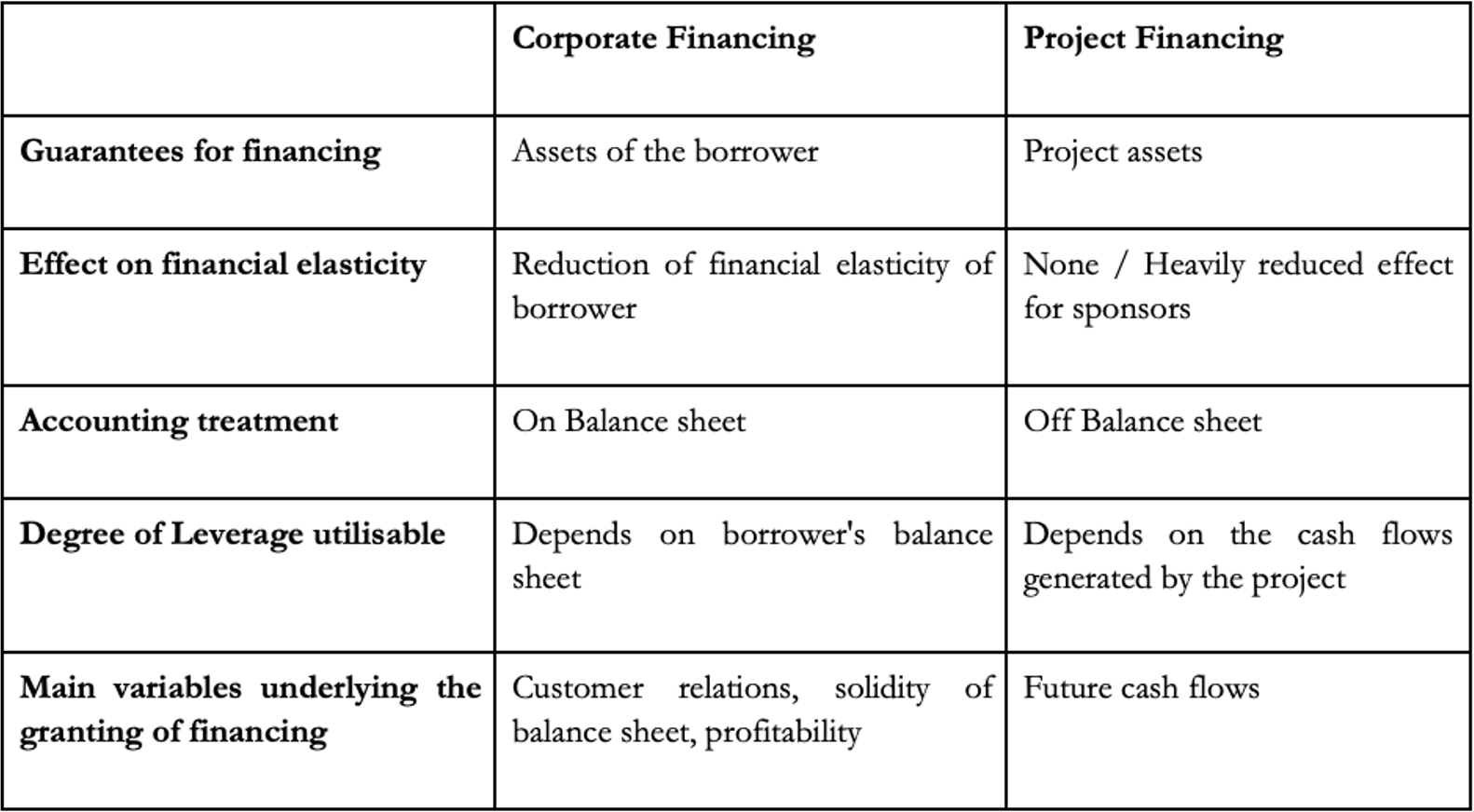

When financing a new project, sponsors (entities requiring finance) typically choose between two alternatives:

- Corporate Financing: The new initiative is financed on the balance sheet of the existing company.

- Project Financing: The project is incorporated into a separate economic entity—an SPV—and financed off-balance sheet.

Corporate Finance involves using the assets and cash flows of the existing company to guarantee credit. If the project fails, all of the firm’s assets and revenues can be used to repay creditors, which may reduce financial flexibility and increase risk for the entire company. Project Finance, on the other hand, keeps the project separate from the sponsoring firm. If the project is unsuccessful, creditors have limited recourse to the sponsor’s assets, minimising the financial impact on the parent company. This approach isolates risks to the SPV, offering a higher degree of financial flexibility for the sponsoring firm.

Source: Corporate Finance Institute, BSIC

In brief, corporate financing uses the borrower’s assets and cash flows as collateral, thus putting the entire company at risk if the project fails. It’s recorded on the company’s balance sheet and depends on its financial health for leverage. In contrast, project financing separates the project from the parent company through a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), with only the project’s assets at risk. This approach doesn’t affect the sponsor’s financial elasticity, is off-balance-sheet, and relies on the project’s future cash flows for financing.

Project finance begins with forming a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), a legal entity created specifically for the project. The SPV is responsible for securing financing, contracting necessary services, and managing project operations. Funding typically comes from a combination of debt and equity, with debt often forming most of the capital structure. Lenders carefully assess the project’s risks and potential cash flows to ensure the project will generate enough revenue to cover operating expenses and debt service. One of the critical advantages of project finance is its ability to distribute risks, such as construction, operational, and market risks, among the stakeholders most capable of managing them. This makes it particularly effective for financing large, capital-intensive infrastructure projects. Additionally, the sponsoring company’s financial exposure is limited because the project’s liabilities are confined to the SPV. Even if the project fails, losses are restricted to the capital invested in the SPV, in contrast to corporate financing, where the entire company’s assets might be at risk.

Over time, as the project generates consistent cash flows, lenders are repaid, and equity investors can realise their returns. This makes project finance a preferred method for infrastructure investments, which often have significant upfront costs and extended payback periods. By isolating financial risks and aligning the interests of all stakeholders, project finance ensures that even complex, high-risk infrastructure projects can be successfully executed, fostering long-term economic development and stability.

Public-Private Partnerships (PPP): Crucial for Infrastructure

A Public-Private Partnership is an agreement between a private entity and a public entity (government) that can be used to build, finance and operate projects. Financing a project through this mechanism usually allows it to become viable as many times the capital expenditures for certain projects are very significant for private investors to take by themselves, as well as very risky for governments to do by their own. Moreover, these types of contracts usually have a duration of 20 to 30 years, through which initially the project will be developed, and then operated, while receiving rent from the asset users and potentially from the government. Then after the concession is over, assets are likely to be handed to the government, unless further improvements or rehabilitation projects are contracted.

Most PPP’s are for new developments, also called greenfield assets. However, can also be formed with the purpose of transferring responsibilities for the upgrade and management of existing assets to a private company. In any way, PPP contracts are measured in terms of outputs rather than inputs, this means that they specify what I required rather than how it should be done. Moreover, one of the main characteristics of a PPP contract is that it joins together multiple project phases and functions. However, the functions of the private parties change a lot depending on what is expected and the type of asset. Some of the typical functions include Design, Build/Rehabilitate, Finance, Maintain and/or Operate. For the provision of the services, an SPV is usually formed.

Another important feature of PPP’s is their payment mechanism. The private party, which is the one that provides/provided the service is entitled to collect fees from the users, from the government, or from a combination of both, with the defining characteristic of payment being contingent on performance. Under user-pays PPP’s, such as toll roads, the private party provides the service to third parties and charge them for the service. The fees can be supplemented by government payments, for instance, in cases where the tariffs are capped to some users, or subsidies to investment at the completion of certain milestones. Under government-pays PPP´s, the government is the sole provider of revenue for the private operator. Payment depends on the type of asset, but usually it is measure in volume or fixed periodic payments are made. For example, measuring how many patients are treated in a hospital and paying the operator based on that, or paying a fixed monthly feee to a free highway operator.

Infrastructure Investments In Our Day-to-Day

Toll Roads in Italy

Toll Roads are appealing as an infrastructure asset class as they exhibit many attractive characteristics. They provide a high level of recurring income, which can increase smoothly with inflation, and are often monopolies, with high barriers to entry but low capital expenditure once built. For investors, the business model is very simplistic, making it easy to forecast future cash flows and to make valuations, which is desirable, and its low-risk nature leads many investors to finance investment with high levels of debt.

The private toll road operator is typically offered a concession contract by a public sector operator. The details surrounding the concession contract are key and will ultimately determine the profitability of the project for the toll road investors. The concession terms will cover areas such as toll rates, duration of the concession, and maintenance requirements. Sometimes the concession agreement may involve a revenue sharing agreement with the public sector. While many of the financial modelling assumptions will be set in stone from the concession agreement, there are still a large number of variables which are uncertain. The most significant of which is traffic volumes which are influenced by macroeconomic factors, consumer trends, environmental factors.

In Italy toll roads, known as “autostrade,” typically charge based on the distance travelled and the toll-road tariffs in Italy are mainly set using a “regulatory asset based system” (RAB). Annual tariff adjustments will be made using various inputs including inflation projections and the revenues and costs of the concession operator. In 2022 for example “Autostrade per l’Italia raised its tariffs by 2% from 1 January, with a further increase of 1.34% in July”.

Autostrade per I’Italia (and its group of companies) (ASPI) operates more than 50% of the toll roads in Italy (in terms of distance). They are 88.06% owned by Holding Reti Autostradali who are in turn 51% owned by CDP Equity, 24.5% Blackstone Infrastructure [NYSE: BX] and 24.5% by Macquarie Asset Management, with 6.94% is owned by Appia Investments and 5% by Silk Road Fund. In June 2021, the investor group led by Italian state lender CDP reached an agreement with Atlantia SpA to buy its controlling stake in Autostradeper l’Italia SpA. ASPI’s latest results indicate that 2023 traffic performance is finally above pre-pandemic levels. Toll roads as an infrastructure asset are lucrative, and have a highly consistent and stable cash-flow, which remains similar year round, offering investors a safe, but slightly-lower return investment.

Airports in London

Airports are attractive as infrastructure investments for numerous reasons, including the fact that they have strong pricing power given the lack of competition and extremely high barriers to entry due to large capital investment, environmental constraints and regulation. Airports have two main customer groups, airlines, and passengers. Their revenue can be broadly split into two streams: aeronautical revenue and non-aeronautical revenue. Aeronautical prices are specifically controlled. For example, Gatwick Airports Aeronautical price cap is currently RPI +0% set by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). Non-aeronautical prices are not always specifically controlled and can be increased through optimising retail space and car parking. This is attractive for infrastructure investors as pricing power coupled with RPI linked aeronautical revenues and rising non aeronautical revenues means predictable inflation linked cash flows. On the negative side, because of the huge capital outlay, airports are exposed to black swan events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

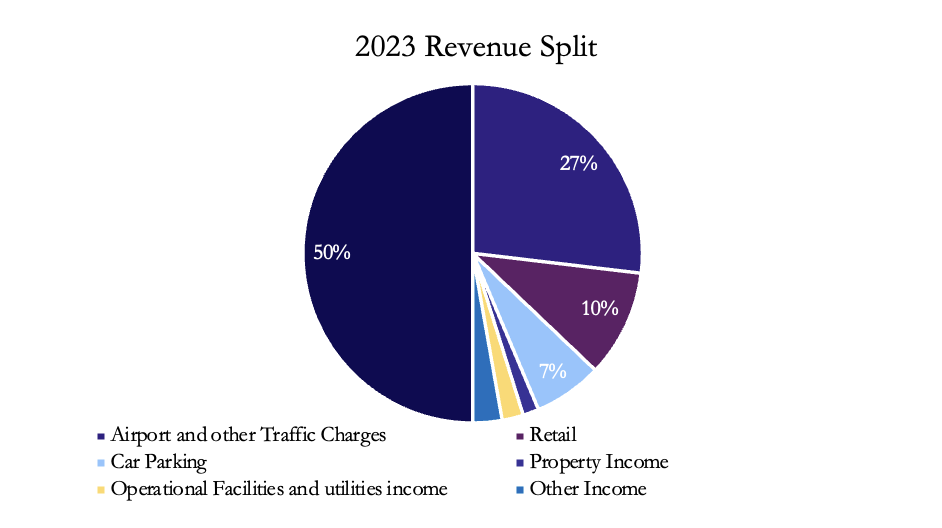

Gatwick Airport is strategically located just south of London, and is the second busiest airport in the UK, flying 41 million passengers per year claiming the busiest single-runway airport in Europe. Since May 2019, Vinci Airports, a global leader in airport management and operation have been the majority shareholder with a 50.01% stake. It is a subsidiary of the French multinational construction company Vinci SA. It was reported to have paid £2.9bn for the stake, with the remaining 49.99% owned by others including Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP). “GIP halved its stake to 21%, while Abu Dhabi Investment Authority kept 7.9%, California Public Employees’ Retirement System 6.4%, National Pension Service of Korea 6% and Australia’s Future Fund Board of Guardians 8.6% (Reuters)”. The GIP-led consortium initially bought Gatwick from BAA for £1.5bn in 2009 who were forced by the Competition Commission to sell it due to competition concerns. The sale to Vinci valued the airport at just under £6bn. Since 2009 Gatwick has paid dividends of about £1.5bn. Despite GIP and partners buying at £1.5bn, paying out £1.5bn in dividends and selling half of the airport for almost £3bn, they still hold a stake valued at £3bn. The large dividends paid out, and the increasing valuation despite the pandemic, show the high growth potential of Gatwick. Below is the revenue split for 2023. Interestingly only 54% of revenue is generated from Airport traffic.

Source: London Gatwick Bond Base Prospectus 2024, BSIC

Investing in airports comes with risks. One of the major risks is exposure to airlines. According to London Gatwick’s Bond Base Prospectus 2024, there is a reliance on a few major airline customers. The top five airline customers (easyJet, British Airways, Vueling, Wizz and TUI) “accounted for 78% of total air transport movements and 79% of passengers” in 2023. Historically, some airlines have had financial difficulties as they have faced fluctuating demand, volatile fuel prices among other issues. If individual airlines faced financial problems in the future, both the aeronautical and non-aeronautical revenues would be vulnerable. Despite the general optimistic outlook for the airport, the key to long term growth is a successful decision on its planning application to bring its spare runway into routine use which could double the number of passengers to 78 million.

Heathrow Airport is the main international airport serving London and is the UK’s busiest airport by passenger numbers and is the fourth busiest airport in the world. Heathrow generates 67% of its revenues from aeronautical, a significantly higher percentage than Gatwick. On 17th June 2024, it was announced that the largest shareholder, Ferrovial and various other shareholders agreed to sell a 37.62% stake, with 22.6% going to Ardian and a 15% to Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund. The consideration of the deal was £3.26bn. Ferrovial have been trying to sell their stake since 2023, but the deal was delayed as other shareholders chose to exercise their right to sell a portion of their shares under “tag along rights” embedded in the shareholder agreement. For Ferrovial, the deal represents a large windfall, and some analysts have said the deal will assist Ferrovial with reducing their net debt and potentially paying more dividends. The Saudi Public Investment fund (PIF) has recently been a major investor around the globe, and they were also part of a consortium that bought Vodafone’s towers unit in 2022, as they aim to reach $2tn in assets by 2030. This purchase illustrates their willingness to diversify their portfolio away from oil, and into more stable assets like infrastructure.

Like Gatwick, Heathrow is heavily exposed to a few airlines. The outlook for Heathrow is bullish, with strong demand for air travel globally contributing to revenues due to its role as a hub airport providing a steady stream of passengers. If the airport was able to expand, including the provision of a third runway, it could significantly increase capacity and revenue, although this looks unlikely at present. There is some uncertainty over regulation and government policy on aviation in general as the new labour government have not revealed policy positions in any detail.

London City Airport is the most central of all the London airports and is in close proximity to Canary Wharf and the City of London. It is owned by a consortium made up of Alberta Investment Management Corporation (25%), OMERS Infrastructure (25%), Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (25%) and Wren House Infrastructure Management (25%). They purchased it form GIP and Highstar Capital in February 2016 (reportedly for around £2bn). Since the acquisition, the airport grew revenues 14% in the year to December 2023 transporting 3.4 million passengers in the year. The airport returned to operating profit (£6.7mm) for the first time since the pandemic. With the ownership being more shared amongst investors, conflicts of interest surrounding the future plans of the airport may arise, with each institutional investor potentially having a different outlook.

The main reason turnover rose was due to passenger numbers increasing from 2.9mn to 3.4mn, however these numbers still remain well below the peak of 5.1mm in 2019. In August this year, the new Labour government signed off on the airports plan to grow passenger numbers by nearly one third from 6.5mm per year to 9mm by 2031.

London Luton Airport is owned by London Luton Airport Limited, a company owned by Luton Council. In 1998, London Luton Airport Operations Limited (LLAOL) entered into a Concession agreement with the Council for the management and development of the airport, with the agreement lasting until 2032. Aena [BME: AENA] (51%) and Infrabridge (49%) are the two shareholders of LLAOL and LLAOL is required to pay Luton Council a Concession fee based on passenger volume. Revenue in the year 2023 was £296mm with profits of £68mm (2022 £51mm). Aeronautical income is 46%. In 2023 Luton served 16.2mm passengers. The joint ownership structure allows the burden of risk to be shared between the private and public sector, which may help the airport stay focused on long-term goals rather than achieving short-term profits.

Moreover, a recent study by University of Alberta showed airports performed better when owned by private equity funds. A total of 2,400 airports around the world were examined and “those owned privately rather than publicly were more efficiently run”. Furthermore, the study found that of the 437 privatized airports, the 102 that had been acquired by an infrastructure fund outperformed. The authors of the study believed that this is because PE infrastructure funds are “closed in with a limited term of about 20 years” and they are motivated to invest in improvements to increase efficiency. Take Gatwick for example, who are constantly innovating and investing and were the first airport to install e-gates, leaders in self-baggage drop-offs, aircraft queuing systems and continue to innovate and drive efficiencies. This long-term outlook of improving efficiency and customer service at airports is they key driver for the growth of airports as an infrastructure asset.

Telecom Towers Investments – KKR Recent Investments

On June 24th 2024, Telecom Italia (TIM) [BIT: TIT] finalised the sale of its fixed-network line grid and wholesale operations, known as “NetCo”to KKR [NYSE: KKR] for €22bn. This transaction was carried out through FiberCop, a subsidiary which TIM has a 58% stake, which was then acquired by KKR. A Master Service Agreement (MSA) was also included in this deal. An MSA outlines the terms and conditions of the future relationship between the two parties, which can include the type of services provided and the payments for these services, alongside the duration of the agreement. For TIM and FiberCop, this contract spans 15 years, where FiberCop will provide a variety of infrastructure services to TIM. Notably, there does not exist any requirements for the amounts needed to be purchased, enabling TIM to manage costs more effectively through adjusting the volume purchased based on current demand. This financial flexibility helps TIM to improve its financial health.

The primary motivation behind the sale for TIM, was to improve its financial stability. Pre-deal, TIM’s total debt was estimated to be €25bn and it is estimated that this was reduced by €14bn post-deal. Moody’s reacted by upgrading Telecom Italians senior unsecured notes to BA3 from B1 citing a “significant improvement in the company’s financial profile thanks to the expected debt reduction of more than €14bn”. Additionally, KKR will be able to provide additional capital if required. Strategically, this deal allows NetCo to specialise on improving and maintaining infrastructure and TIM can focus on delivering higher-quality customer service and improving their efficiency. The proceeds can also boost TIM’s competitive rather than all going towards infrastructure investment. For KKR, a firm with a history in managing infrastructure assets, this deal provides not only the steady returns infrastructure offers, but also the ongoing, and projected, growth in the demand for digital infrastructure, as the digital service market continues to grow.

KKR has also been growing its presence in the Latin American digital infrastructure market. On January 24th, 2024, Nexo Latam, a digital infrastructure platform provider, which is backed and financed by KKR, acquired about 1,100 wireless towers from Tigo Colombia, a subsidiary of Millicom. The was deal valued at approximately $1bn, and Nexo Latam will lease these towers back to Tigo Colombia. This sale will improve Millicom’s liquidity and enable it to focus more on increasing its operational efficiency and improving its telecommunication services rather than managing infrastructure. For KKR, they plan to capitalise on the rising demand for digital infrastructure, which is growing particularly strongly in the Latin America region, due to the late transition to digital services.

Another recent deal which was announced by the US Department of Commerce in March 2024, was that KKR plan to invest $400mn to acquire around 2,000 telecoms towers in Philippines. This follows previous deals KKR has made in the Philippines, such as the purchase of a large stake in Pinnacle Towers in 2020 and the purchase of 3,529 towers for approximately $1bn in a deal with Philippines’ Globe Telecom. Additionally, KKR acquired 1,012 towers from PLDT in March last year. A partnership with Pinnacle Towers, one of the largest telecom tower operators in the Philippines, demonstrates KKR’s interest in this market in the Philippines, which is a country still in the early stages of its digital transformation. For Pinnacle Towers, they will have access to the capital to scale rapidly and become a stronger player in the Philippines market, without the worry of seeking funds.

Moreover, in March 2024, Vodafone Group [LON: VOD] entered into a co-control partnership with GIP and KKR to manage Vantage towers, which controls and owns a large portion of telecommunication towers across Europe. The partnership involves GIP and KKR gradually purchasing stake of Oak Holdings, Vantage’s controlling entity, and they recently sold off an additional 10% stake. Vodafone claim the total proceeds from the sale of Vantage Towers is €6.6 bn, and as it stands, have left Vodafone with a minority status in Vantage for the first time, with 44.7%, but they still own 50% of Oak Holdings, which has 89.3% ownership in Vantage Towers so will still have effective co-control. For Vodafone, which reportedly holds close to €49 bn worth of total debt, these series of sales allow it to pay off some of their debt, alongside enabling them to benefit from the expertise in managing infrastructure assets which GIP and KKR possess. For KKR and GIP, the upcoming 5G technology allows room for potential growth in the telecommunication industry, in which they hope to reap the returns it has to offer.

Conclusion

Overall, as we can see from what has been discussed above, infrastructure, as an asset class, has been growing and will continue doing so over the next years. Currently the world is experiencing aging infrastructure, with the further risks associated to climate change and the pending energy transition, so large investments are necessary in the years to come. Moreover, as an asset class, while it doesn’t provide stellar returns to Limited Partners as other forms of private investments might do, it does provide stable returns. At a time in history when there is so much geopolitical volatility, investing in assets that provide stable returns provides a safety net for investors, securing them returns for the years to come. Moreover, while Infrastructure is an asset class that is less attractive to people, it shouldn’t be overlooked. Not only because of its growth over the past years or its future demand, but because of its presence and importance in our daily lives.

0 Comments