Introduction

The global toy sector stands at a crossroads, balancing tradition with rapid transformation. Indeed, once dominated in the 1980s by household names such as Transformers, G.I. Joe, Hot Wheels, Barbies and the iconic LEGO bricks, the industry enjoyed double-digit growth during the Western economic boom. At that time, strong consumer demand and limited competition secured wide profit margins and global recognition for these brands.

Nowadays, however, the landscape has shifted dramatically, with an average growth rate of only around 4.4% over the last decade, according to the ECSIP Consortium, the toy market faces a far more mature and competitive environment within a stagnant market. Large companies are now challenged by digital substitution, changing consumer preferences, and rising pressure from innovative newcomers and collectibles-driven brands. This scenario is forcing legacy players to rethink their both strategic and finance models, balancing nostalgia with innovation to maintain relevance in a rapidly evolving global market.

Company deep dives – LEGO from crisis to “best-in-class”

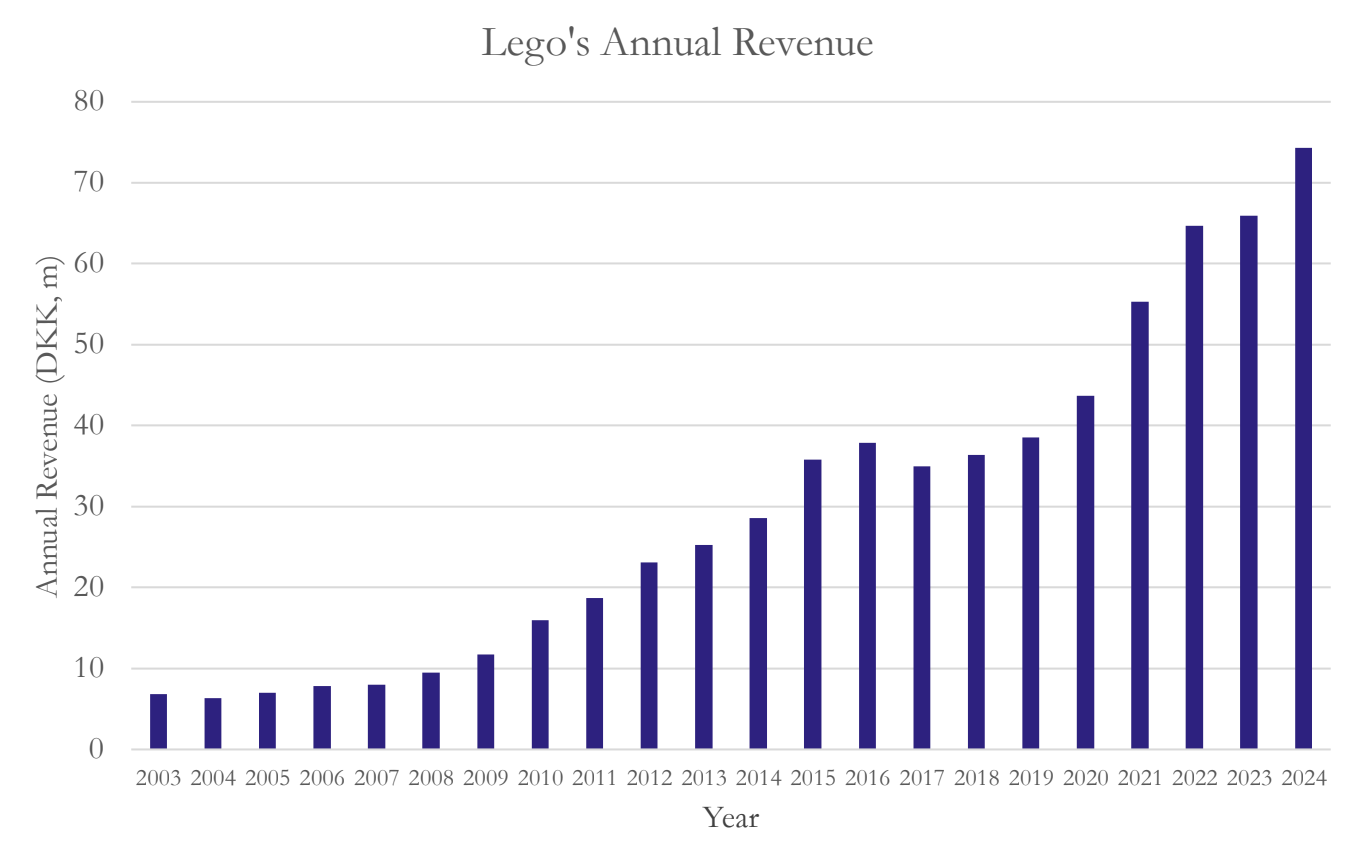

Lego struggled in the early 2000s, facing near collapse in 2003-2004, after posting its worst financial results to date with revenue down 26%. This significant underperformance was mainly due to an overdiversification of their product line. Ventures into video games, clothing, theme parks, and overly experimental toy lines all proved to be very unsuccessful, draining resources and distracting the company from its core business.

In 2004, to address this underperformance, the company implemented a number of management changes, including hiring Jørgen Vig Knudstorp as CEO. Upon becoming CEO, he immediately implemented a strategy of going back to basics. The firm started refocusing on its core product, the Lego brick, and dramatically reduced SKUs. This involved standardising colours, limiting the introduction of new moulds, and eradicating underperforming sets. All these changes helped the firm reduce costs and improve the reliability of their production.

In addition, Lego decided to divest its non-core businesses, most notably selling its Legoland theme parks to Merlin Entertainments in 2005, to help reduce its debt burden and refocus their efforts on their core product offerings. On the operational side of things, Lego outsourced their production to Flextronics in 2006, to quickly cut costs. However, by 2008, the company switched course and decided to produce in-house again because Flextronics struggled to meet Lego’s quality standards and weren’t able to quickly ramp up production in response to toy market seasonality. Instead, Lego decided to strategically invest in manufacturing plants globally in Mexico, Hungary, and later China, countries known for their cheap yet reliable manufacturing expertise, to help build Lego’s key parts. This shift is what led to the establishment of Lego’s hybrid model, where they are able to maintain a strong control over their brand image by producing their most important parts to a very high standard in-house, while at the same time outsourcing their non-core production, enabling them to reduce its costs while at the same time not sacrifice the company’s high quality and brand image.

Furthermore, Lego has also managed to rebuild its consumer engagement. Fan engagement programs like Lego Ideas and The Lego Movie in 2014, which generated $468m, have both increased the brands global presence, attracted more customers, and boosted toy sales.

By 2015, Lego was able to overtake Mattel, becoming the leading global toymaker by revenue. Its turnaround helps highlight how efficient operations and strong brand stewardship can revive a legacy company. Today, Lego continues to perform well against the broader toy industry.

The Two Colossi: Hasbro vs. Mattel

The Two Colossi: Hasbro vs. Mattel

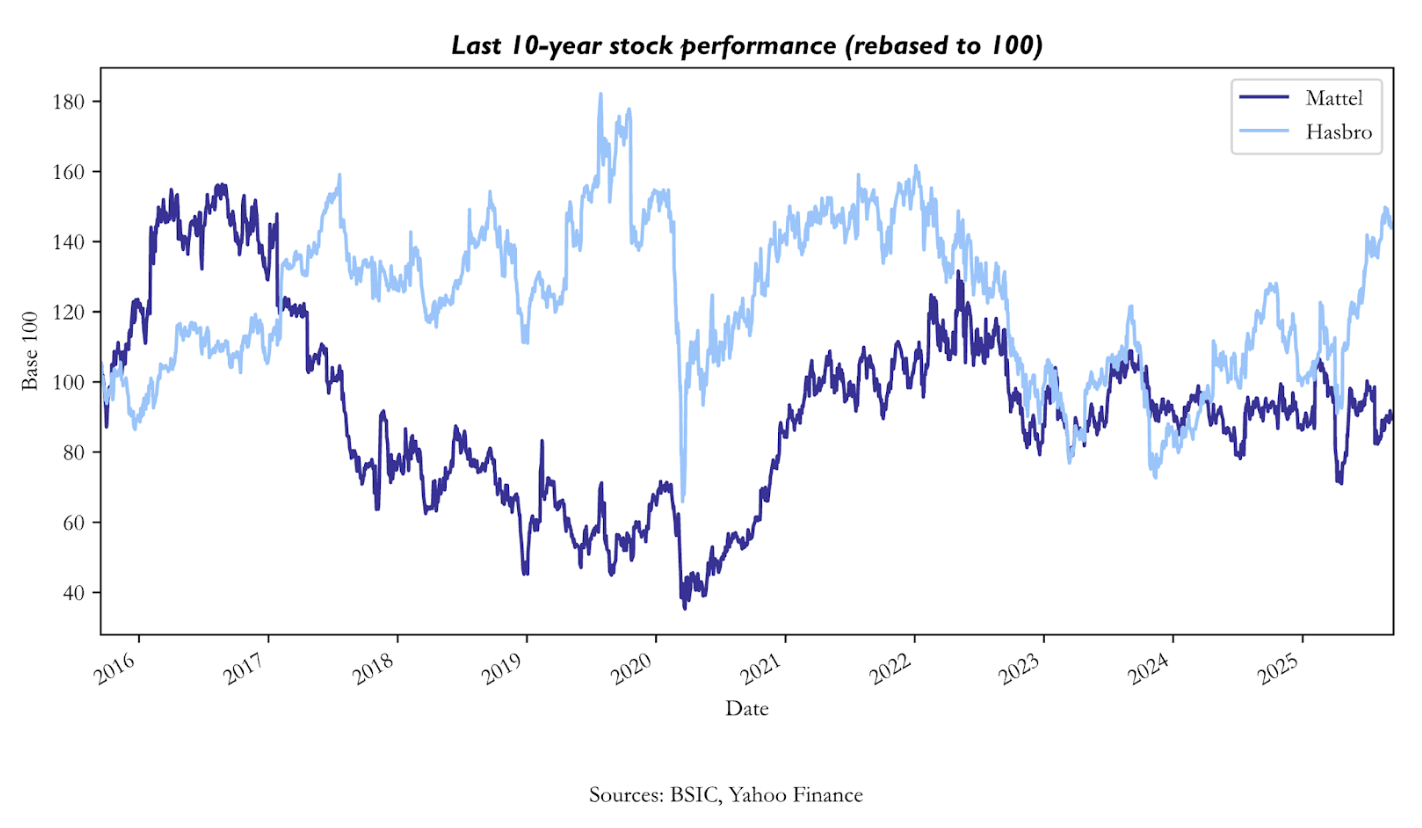

Hasbro [NASDAQ: HAS] and Mattel [NASDAQ: MAT] have long been the two largest U.S. toymakers, with market capitalization of $10.8bn and $5.7bn, respectively. Both companies are now facing a shifting consumer environment and are seeking to adapt to the new digital gaming world, making use of the broad IP portfolio they own. Although reports surfaced in 2017 of potential merger discussions between the two rivals, no transaction ultimately materialized.

Hasbro

Founded more than 100 years ago and headquartered in Rhode Island, Hasbro has established itself as one of the most recognizable players in the global toy industry. Its portfolio includes iconic brands such as Magic: The Gathering, Dungeons & Dragons, Monopoly, Nerf, Transformers, Play-Doh, and Peppa Pig.

Under the leadership of the previous CEO, Brian Goldner, the company aimed to create an entertainment conglomerate, highlighted by the acquisition of Entertainment One, a global independent studio, in 2019 for roughly $4.0bn. Over the last years, however, the new CEO, Chris Cocks, has shifted strategy, steering the company to refocus on its strongest intellectual property while divesting non-core assets. As a result of this strategy, the company first sold the music production division of Entertainment One in 2021 for around $385m and then the TV and film division for around $500m in 2023. Although Hasbro recorded steep losses on these transactions, the choice aligned with the strategy named “Blueprint 2.0”, introduced by the new CEO, which prioritized focus on the key brands and IP that the company possesses. In parallel, Hasbro also announced a new restructuring plan for the company, which included cutting around 1000 jobs, which represented around 15% of the global workforce

In February 2025, Hasbro unveiled a new strategic plan, set to guide the company through 2027. The revised strategy is based on two key pillars: leveraging its strong portfolio of brands and intellectual property to return to revenue growth, as well as expanding its licensing agreements. In particular, Hasbro has turned to a licensing-driven model for location-based entertainment. For instance, it partnered with Merlin for the creation of Peppa Pig theme parks in the US and Europe, with a fourth one expected to open in China. These licensing agreements allow the company to generate recurring royalty income without incurring heavy capital expenditures. Moreover, in addition to location-based entertainment, Hasbro has expanded licensing into other areas, such as digital gaming, one of the fastest-growing segments in the toys market and where Hasbro has become the largest licensor worldwide.

As a result of the new strategic plan followed by the company, FY24 revenues totalled around $4.1bn. In terms of segments, Consumer products recorded $2.5bn of revenues, down 12% from the previous year, while Wizard of the Coast and the Digital Gaming segment recorded $1.5bn, up 4% from 2023. Interestingly, though, the operating margin on the Consumer products segment was 6.0%, while for the Wizard of the Coast and Digital Gaming business it was 41.8%. This difference helps to explain the rationale behind Hasbro’s focus on digital gaming, partnerships, and licensing, compared to the traditional production of toys.

Mattel

Mattel, on the other hand, was founded in 1945 and is headquartered in California. Among its main franchise brands, we can find Barbie, Hot Wheels, Fisher-Price, American Girl, Thomas & Friends and UNO.

Since the current CEO, Ynon Kreiz, joined the company in 2018, Mattel started to develop its brands through franchise agreements and partnerships, similarly to Hasbro. In particular, Kreiz leveraged its background in entertainment and started a new Mattel Film division. Differently from what Hasbro initially did, though, Mattel always relied on third-party studios to create content, rather than acquiring and running an internal production studio. The large success of the Barbie movie, which was produced with Warner Bros., has validated this approach, as the movie earned more than $1.4bn at the box office. Following this large success, Mattel is continuing to try and benefit from its broad IP portfolio, by investing in new film, television, and digital projects, with more than 14 productions in place.

Moreover, like Hasbro, Mattel is not committing capital to its own physical infrastructure. The Mattel Adventure Park in Arizona and the building of a second site in Kansas are undergoing with the partner Epic Resort Destinations, which again allows avoiding direct capital expenditure.

Financially, Mattel’s margins have improved over post-turnaround, with operating margins now quite steady in the 10%-13% range. The company is still more exposed to the cyclicality of core toy demand than Hasbro’s Wizards-driven profit base, with revenues slightly declining in FY24, down 1% compared to the previous year.

Pop Mart — Labubu and the Collectibles Boom

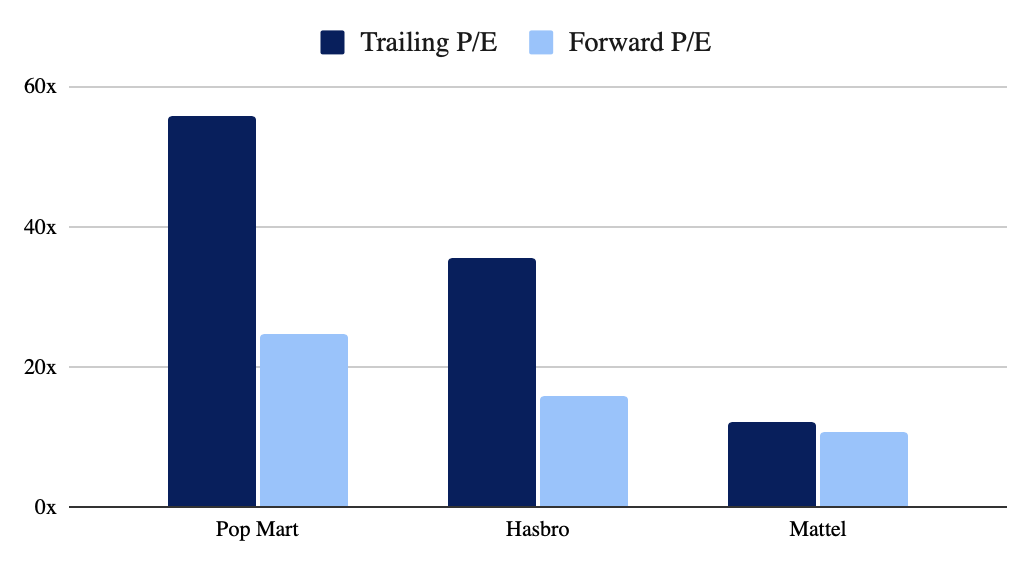

Pop Mart [HK:9992], a Beijing-based, Hong Kong-listed toymaker, has disrupted the market, hitting a lofty market capitalisation surpassing $50bn. Founded in 2010 by Wang Ning, this juvenile company towers over the 100-year-established valuations of Mattel [NASDAQ: MAT] and Hasbro [NASDAQ: HAS]. At this moment, Pop Mart’s trailing P/E is 55.72, exceeding that of Mattel (12.02) and Hasbro (35.61). This multiple discrepancy is credited to Pop Mart’s robust IP model and rapid international expansion, which have bolstered investor expectations for continued innovation and growth.

The core business of Pop Mart revolves around intellectual property (IP) toys, both proprietary and licensed non-proprietary, which are sold primarily in the “blind box” format. In 2016, Pop Mart launched the first of such products, the “MOLLY” blind boxes; however, the notorious “Labubu”, an “ugly-but-cute” creature, propelled Pop Mart to fame. “The Monsters” range in which the Labubu belongs to accounts for 34.7% of Pop Mart’s total revenue as of this year, raking in $669.88m. Pop Mart operates a total of 56 IP characters, of which it licenses a large portion, such as coveted Disney characters and “Crybaby”. The success of the IP blind-boxes lies in the fact their uniqueness appeals to different consumers, their affordability ($10), and that they capture consumer irrationality. Given the concealed nature of “blind boxes”, the collectible purchased is unknown until one opens the box, which drives repeat purchases as collectors strive to complete ranges of character lines. Particularly, some of the rarer collectibles can reach three times their standard price in secondary markets. The scarcity-driven demand and strong monetisation of IP have fueled net income, which YoY improved 188.7% from $148m to $420m, and revenue at $1.8bn, a 106.9% increase since 2023. Strong profitability, innovation in product design, and indications of a loyal consumer base, have thus supported an elevated P/E.

Pop Mart’s ambitious international expansion has also played a critical role in Pop Mart’s valuation. With 571 stores across 18 countries, including flagships in the U.S., U.K., Japan, and South Korea, Pop Mart has solidified its position as an international brand. Alongside brick-and-mortar stores, the company operates almost 2,600 “roboshops” or vending machines, which are particularly cost-effective as they require no manpower. This multichannel operational model facilitates 40% of Pop Mart sales, which come from overseas. This diversification of revenue streams has helped shield Pop Mart from regional market downturns, supporting Pop Mart’s strong P/E. However, recent economic downturns have, in fact, contributed to Pop Mart’s recent success. This is due to the “lipstick effect”, whereby consumers who would normally buy luxury goods turn to less expensive discretionary goods, such as Pop Mart’s collectibles.

Considering Pop Mart’s IP portfolio, optimistic financial performance, and global presence, the company appears well-positioned to maintain its lead over competitors such as Mattel and Hasbro. While a deflated forward P/E (24.75) raises some concerns about “fad fatigue,” executives remain confident in achieving significant revenue growth for 2024. With new IP launches, including a mini Labubu range, Pop Mart demonstrates its intention to sustain consumer interest and continue innovating to meet evolving market demand.

The Future of the industry

These cases highlight how effective brand stewardship, capital-light operational models, and the systematic monetization of intellectual property are becoming the real key levers of competitiveness in the toy sector. With the stagnant market, firms that efficiently reallocate capital, leverage scalable IP across media and experiences, and maintain disciplined cost structures within their M&A operation are best positioned to sustain margins and defend market share in an increasingly mature and innovation-driven industry.

0 Comments