Two years ago, in our article “Dollar repatriation? Different story told by cross-currency swap”, we have looked into the 2018 environment of the cross-currency basis market. This year has brought about a major funding crisis and that caused this topic to be worth revisiting since COVID-19 led to significant changes in the dynamics of the trading of this instrument.

Introduction

Some of the most well-known simplifying assumptions of the economic states of the world do not tend to hold in trading realities of many markets. One such example is the cross-currency basis which is a violation of the commonly taught covered interest parity (CIP). Namely, under the CIP, it should be assumed that the interest rates of two countries and the spot and forward exchange rates on their currency pair are in equilibrium, i.e. that the interest rate spread between the two currencies in the cash money markets should equal the differential between the forward and spot exchange rates.

Let us apply this macroeconomic theory onto the financial instrument that is the cross-currency swap. To put it simply, a cross-currency swap is used to transform a funding position in one currency for a funding position in another currency. Even though most OTC derivatives trade as contracts for difference, the exchange of funding makes a cross-currency swap a physical swap, and the underlying is a financial asset (cash i.e. the notional) rather than a hard commodity.

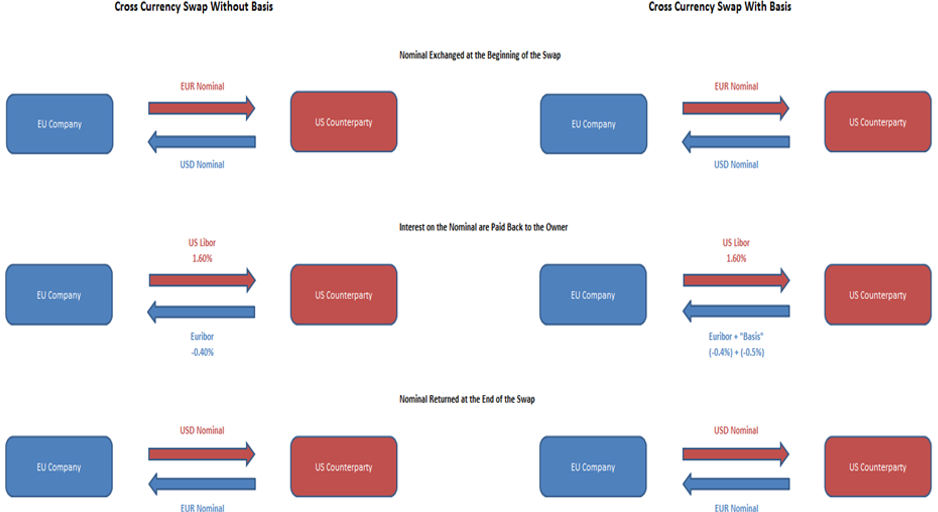

This is a good time for an illustrative example. We consider a French company doing business in Europe, taking a one-year EUR cash loan from a bank to fund its 100% cash M&A transaction for a US target. It does so through a cross-currency swap not only to avoid being exposed to a US liability while it experiences its cash inflows in EUR, but also because it might have a lower synthetic borrowing cost by taking out a loan in EUR and then swapping to USD rather than borrowing USD directly in the US market. Simplistically speaking, however, it is primarily in order to hedge the foreign exchange risk that the company enters into a one-year EURUSD currency swap with their bank counterparty. The company uses the cross-currency swap to exchange the entire EUR notional it received from the loan for the dollar notional it will use to fund the US M&A transaction at time t=0 at today’s spot that is pencilled into the contract, agreeing to swap the same amount of notional back in one year’s time, at t=T. Not only is this an FX hedged transaction (given the predetermined initial and final notional exchange, since the time t=0 spot exchange rate is used to calculate both the initial and final notionals), but that notional conversion exchange rate is also usually predetermined on the day of the execution, even before the live transaction itself, to avoid any slippage in the highly volatile FX market. In the intermediate interest periods, since the company does not technically own the USD, it will need to pay US Libor as interest and by reciprocity receive Euribor from its counterparty, which occurs during a time period t, such that 0<t<T. These intermediate interest rate payments should also be priced such that the CIP holds, assuming zero transaction cost and zero margin that the bank would impose on their client. However, the interest payments just described are not entirely representative of the market given that in reality they include an “additional cost”, which is the long-awaited cross‑currency basis. This “additional cost” comes in the form of the lesser Euribor interest payment that the US bank owes to our French company with respect to the fair value of the Euribor leg, such that now this transaction is no longer at NPV=0 (always disregarding the transaction costs and the bank’s margin).

Source: M&G Investments

Such a basis has only arisen since the Great Financial Crisis. Prior to 2008, all banks assumed they could roll unlimited funds at Libor flat, meaning that paying a premium on dollar funding was unthinkable. So why has this basis emerged?

In most simplistic terms, it is due to the contractual power of the investor counterparty that is the holder of a scarcer currency. Given that the USD is the most sought-after funding currency, the counterparty lending the dollar will ask for a premium. Hence, the borrowing party will pay US Libor and in turn receive Euribor plus the cross-currency basis, which is in fact negative, and therefore represents the “additional cost” for the USD borrower. It follows that when we observe a steadily decreasing (i.e. a more negative) EURUSD cross-currency basis, we will know that the dollar is becoming steadily scarcer or less liquid with respect to the euro.

More generally, the reasons have to do with the structural changes that occurred after the crisis. Since then banks tend to discount cashflows back into their domestic currency. Moreover, USD is broadly considered to be the global “risk-free” currency and thus most other funding markets trade at a premium (negative basis spread) to the USD. Another important reason is the increased importance of the QE-policies that significantly affect the supply and demand imbalance within a particular debt market.

Market Considerations in a Funding Crisis

The above characterizations will now allow us to steadily transition into observations of how cross-currency trading changes during the funding crises and how it did so during the most recent one, assuming that we take into consideration as the most important catalysts of change the FX markets, Libor fixings, futures convergence trades, central bank operations, and client demand.

As can be observed in the euro-dollar and yen-dollar cross-currency basis pairs (notice the inversion of the definition of the USDJPY currency pair to yen-dollar cross-currency in order to stay consistent given that most funding currencies trade at a negative basis, i.e. a premium to USD as mentioned earlier) the cross-currency basis swap has dropped dramatically around March of this year. This drop has been caused by the market-wide rush to secure the dollar funding in times of its scarcity. In particular, the US dollar funding demand has grown and is likely to increase further as demand from corporates and financial institutions should rise with pandemic-related lockdowns, supply chain disruptions, and economic strains.

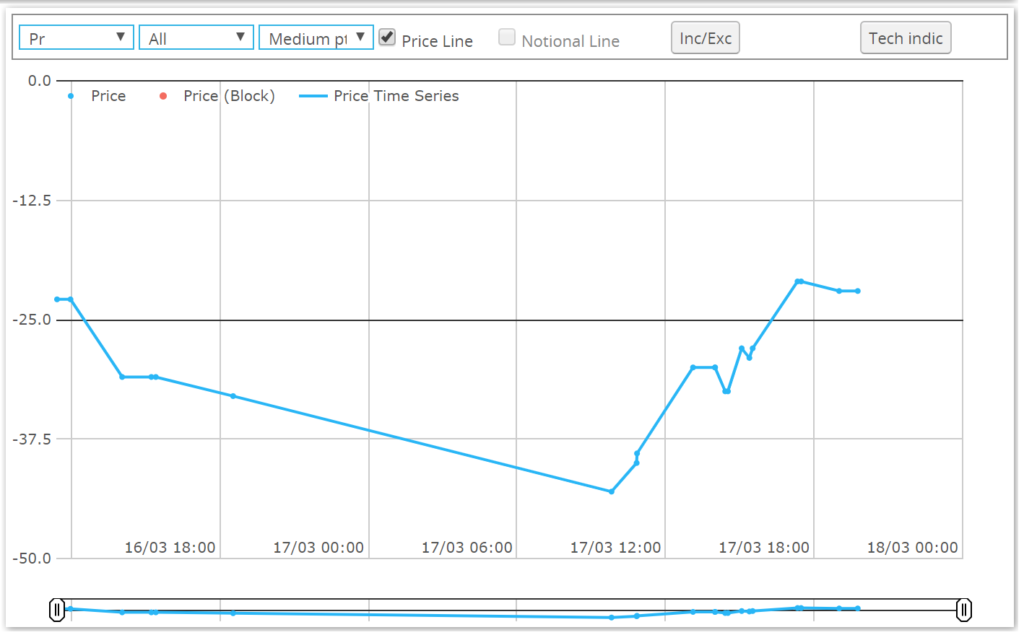

In order to avoid generalizations, let us focus on a representative trading day of the crisis and how basis trading has changed due to some market catalysts. Tuesday, 17 March 2020 saw three strong market indicators of dollar shortage. Firstly, a group of US banks tapped the “discount window” to borrow USD from the lender of last resort. In a reassuring press release, Financial Services Forum tried to de-stigmatize the access to this facility however the markets remained convinced that financial institutions will only continue to access the “discount window” and that this was fuelled by a more permanent shortage. Secondly, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) allocated the entirety of its USD repo facility with approximately 30BUSD worth of bids and the sheer size of the allocation took markets by surprise. Thirdly, the 3m USDLIBOR fixed 16bps higher to make up for a total of 31bps increase starting from the week before. While all this was happening, the EURUSD cross-currency basis took a tumble but has recovered throughout the day as can be observed from the graph below.

Source: CME Group

Wednesday, 18 March saw further developments; namely important central bank auctions of the USD from the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of England (BoE), and the Swiss National Bank (SNB), where the ECB alone allotted nearly 100BUSD. The 3m USDLIBOR moved up by 6bps. Most notably, this period was highly contributing to the volatility of April expiry of Eurodollar futures, given how hedging these daily fixing exposures becomes a primary concern for traders with cross-currency exposure.

The Fed FX Hotline

The surging demand for the USD and early signs of credit and funding stress prompted the Federal Reserve to step in to restore confidence in foreign-exchange markets and allow them to operate normally. On 15 March, the Fed and the five major central banks (the Bank of Canada, the BoE, the BoJ, the ECB, and the SNB) announced an enhancement of existing dollar liquidity swap lines, lowering the price to USD OIS rate+25bps.

Central bank swap lines are bilateral arrangements between central banks that allow member banks of their respective countries to obtain the specific foreign currency. Swap lines aim to ensure that there will be enough foreign currency available in times of market turmoil. A dollar swap line is a short-term lending facility that allows a foreign central bank to borrow dollars from the Fed in exchange for an equivalent amount of its domestic currency. The two banks agree to swap back these amounts at a specified date in the future.

On 20 March, the Fed expanded its swap lines to nine other central banks, including large emerging markets such as Brazil and Mexico. What is more, on 31 March a new temporary repo facility for foreign monetary authorities was established. This was a historic move as it allows foreign central banks to directly enter into repo agreements with the Fed.

Six months after these developments, we are able to examine the most crucial question: have these measures worked? First, it has to be noted that not all countries can benefit from the aforementioned Fed interventions in an equal way. Emerging markets with low Treasury holdings and foreign currency reserves have a limited possibility to access the new Fed repo facility. Moreover, even if certain EM central banks can obtain dollar liquidity, the impact on the broader economy will only materialize if banks are able to pass this cash to households and businesses. In this regard, country-specific policies may prevent dollar funding from being channelled to businesses that need it the most.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, cross-currency bases of several EM currencies widened significantly more than those of developed countries’ currencies. This exemplifies that EM countries face structural vulnerabilities to USD funding stress. In Asia, many EM economies are fiscally strong; however, given their significant role in global supply chains, they require large amounts of USD for their day-to-day operations. Moreover, Asian banks have considerably increased the scale of their cross-border operations (primarily denominated in USD). While Asian banks’ exposure to US dollar funding increases, currency hedging mechanisms and instruments in this region are still underdeveloped.

This explains the fact that while Fed interventions significantly alleviated dollar funding pressure in many markets, in several Asian EM markets cross-currency bases remain wide. If these strains were to persist, they could bring about recessionary tendencies and further aggravate the situation in currency markets.

Conclusion

The cross-currency basis may be the most reactive market leading indicator of a funding crisis and can be used to determine how quickly such a crisis is affecting firstly developed markets and emerging markets, and then on a more granular level, individual countries. Moreover, the “speed” with which the base is declining might be an indicator also of how soon the Fed might or should step in as the lender of last resort for investors and companies that are scrambling for dollars. Lastly, with a more long-term perspective in mind, risks indicated by the widening cross-currency basis, such as the availability of short-term funding, liquidity, and investments should be systematically monitored and addressed, since they may have a ripple-down global effect causing financial instability across all asset classes.

1 Comment

cryptocurrency meaning · 14 November 2022 at 6:25

Cryptocurrency is increasing in each awareness and repute.

The official webpage for the petro on Tuesday printed a guide to

establishing a virtual wallet to carry the cryptocurrency.

Coinbase also permits you to withdraw your coins into a personal wallet if you wish to retailer them.

It is the real value of cryptocurrency – when no one besides you

is in control of your funds, but at the same time, you retain the

rights not only to retailer these funds but also totally handle them in different ways.

“Venezuela is suffering through one of the worst economic crises in trendy historical past, with its national currency, the bolivar, turning into practically worthless,” the

agency wrote. Chainalysis additionally mentioned Venezuela’s national cryptocurrency, the

petro, launched by the country’s “contested government, led by OFAC-sanctioned Nicolas Maduro and recognized for its corruption and human rights abuses.” In May, the U.S.

It was based in secret by Satoshi Nakamoto, and with the intention to scale, it must be continually engineered by a team containing a known psychopath led by a man who one way or the other got the code from Satoshi Nakamoto but appears confused about who he was.

Maduro says his authorities is the sufferer of an “economic warfare” led by opposition politicians with the

assistance of the federal government of U.S.