Introduction

While interest rates were still stuck at historic lows in Europe, news broke in June 2022 that Credit Suisse was about to issue a contingent convertible bond at a yield level of close to 10%. The peculiarity with this type of security is that it is converted into equity in case a trigger event, usually a decrease of the issuer’s capital ratio below a certain level, occurs. While this particular issuance can be seen as an extreme case due to Credit Suisse’s situation, it still showcases the significant pick-up in yields subordinated debt generally offers over more senior securities.

This article first analyzes how the resilience of banks’ balance sheet changed after the financial crisis and how that impacted the market for subordinated debt in Europe. Further, more consideration is given to the current macroeconomic climate and its implications for banks and debt markets. Finally, we present specific securities that offer an attractive return compared to senior debt in this environment.

Regulation as a Driver of Banks’ Capital Structure

After the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) exposed severe shortcomings in the resilience of banks’ balance sheets to absorb losses and withstand external shocks, the Basel Committee initiated the process that led to the development of the Basel III framework. While banks’ capital structure was already regulated before, mainly by the national implementation of Basel I and II rules, the new proposal focused on strengthening the existing framework in several areas.

A key point of emphasis for regulators was the quality of loss-absorbing capital of banks. Specifically that meant that banks were now required to have more than double the previous amount of common equity (called CET1 capital) against their risk-weighted assets (RWAs). The minimum ratio increased from 2% to 4.5% thereby weakening the regulatory allowability of hybrid and innovative instruments that were treated as Tier 1 capital previously. Further, a capital conservation buffer of 2.5% of RWAs was introduced that is designed to absorb initial losses by limiting banks’ ability to pay dividends and bonuses in times of stress.

Besides the strengthening of CET1 capital, further changes included additional capital requirements for banks that are deemed to be of global systemic importance (G-SIBs). Depending on their size these financial institutions are required to have an additional CET1 buffer of up to 3.5% of RWAs. Additionally, to complement the capital ratios, a minimum leverage ratio was introduced to counteract the substantial pre-crisis build-up of leverage while liquidity ratios were introduced to ensure the availability of sufficient liquid funds in times of stress.

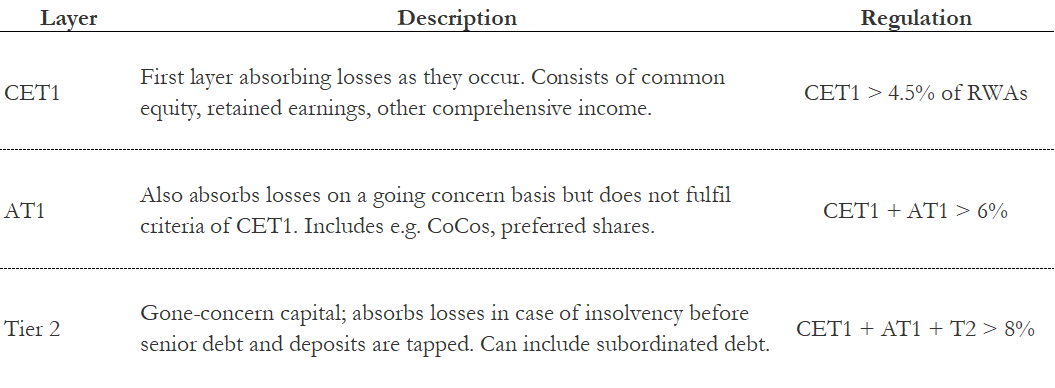

After the implementation of the framework on a national basis, the layers of banks’ regulatory capital can be presented in the following stylized way:

Source: Bank for International Settlements, Bocconi Students Investment Club

Basel III thereby forced banks to build up substantial loss-absorption capacities. As losses occur, these initially affect the so-called ‘going-concern capital’ (CET1 and AT1). When a bank fails, Tier 2 capital (‘gone-concern capital) is used up before further subordinated debt holders and eventually senior creditors, as well as depositors suffer losses. To qualify for each layer, securities have to fulfill strict criteria. All Tier 1 instruments must not have a maturity date and cannot comprise an obligation to distribute dividends. The subordinated debt in Tier 2, among other things, must have an initial maturity of more than five years and not include any redemption incentives.

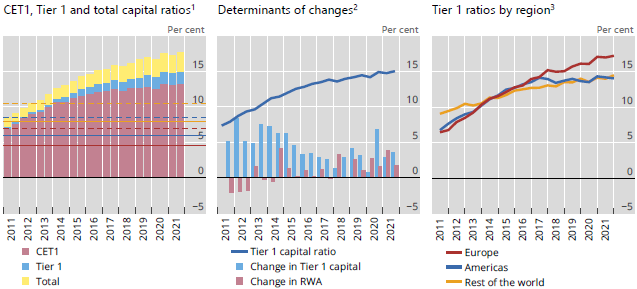

Source: Bank for International Settlements

Following the GFC, these changes led to a substantial increase in capital as can be seen from the chart above from the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s (BCBS) Basel III Monitoring Report.

Across all geographic regions, capital ratios grew substantially over the last decade. This change was mainly driven by an increase in banks’ CET1 ratios while also the other layers were strengthened. Today, banks therefore have much more resilient balance sheets to absorb losses during distress compared to other historical episodes, especially during the GFC and the European Debt Crisis.

Besides the importance of increasing loss-absorbing capacities, research and regulators regularly stressed the importance of subordinated debt in enforcing discipline on banks’ management. Due to their low seniority, subordinated creditors have a stronger incentive to actively monitor banks’ risk taking and thereby lead to more sustainable decision making. This theory is consistent with the empirical observation that subordinated debt shows high levels of risk sensitivity (e.g. Sironi 2003). This also led to proposals that would make it mandatory for banks to regularly issue subordinated bonds to create a liquid market for these securities, thereby complementing the regulation of capital ratios by market discipline. After the financial crisis, the sensibility of such a regulation was called into question, as the implicit guarantee for “too big to fail” financial institutions reduced subordinated debt risk sensitivity (e.g. Pablos Nuevo 2020).

As these regulatory proposals never materialized, the market for subordinated debt remains rather illiquid with an estimated global size for AT1 and T2 instruments of $600bn-$700bn. Further, the liquidity of the market can be impaired by the fact that a substantial share of the debt is privately placed. Nevertheless, the issuance of subordinated debt remains attractive for banks as it is commonly the cheapest way to shore up capital without diluting existing shareholders, leading to a stable supply.

Macroeconomic Environment and Technical Analysis

The current macroeconomic environment is still mostly affected by the Covid pandemic and how world economies have reacted to it.

After the pandemic, the economic climate has been characterised by a tremendous surge in demand for products and services coming out of a nearly two years period of standstill, fuelled by a huge injection of capital and cash coming from central banks and governments. This was coupled with grave dislocations in the global supply chain due to US, Europe and China economies having problems re-establishing production and supply logistics.

The two trends generated an inflation surge not seen in decades. In order to fight this inflation threat, central banks concerted a global interest rates response that has seen US and Europe rates increase 450 and 300bps, respectively over the course of 12 months.

We believe that these considerations are important to discuss how strong the current banking sector appears to investors.

Banks’ Credits Strength

We have seen how banks’ capital ratios have improved over the years, now we will analyse also how the current rate environment is strengthening the P/L of major commercial and retail banks.

The current rate environment, in fact, has been very favourable for banks since the start of the hiking cycle. Although dramatic rate increases have caused some turmoil in the markets, and have spurred an ever-changing expectation of recession, banks have clearly benefited.

This benefit mainly derives from the substantial increase in Net Interest Income (NII), which banks have enjoyed during this cycle. The NII boost comes from the very high deposit beta (difference in the interest rate they charge on their assets vs the near zero interest they pay on deposits) that the banks have had the chance to implement. This is at the heart of the record earnings numerous banks posted in 2022, particularly in the last quarter of the year. Among these banks are: UniCredit, Intesa Sanpaolo, Deutsche Bank and BNP Paribas.

UniCredit posted a revenue of 5.72 billion in the last quarter. It also posted a 47.7% jump in 2022 net profit, which totaled to €5.2bn, up from €3.5bn the previous year. Intesa Sanpaolo’s Q4 2022 operating income was up 13.1% to €5.67bn, from 5.0 in Q3. Net income was up to €1.1bn, from 0.9 in Q3, exceeding analysts’ expectations. Deutsche Bank posted Q4 net revenue of €6.32bn, and a net income of €1.8bn, versus €145mn a year before. BNP Paribas also showed very solid results, with revenues up 9% since 2021, and net income for the whole year at €10.2bn, up 7.5% YoY.

All banks have also shown very robust capitalization ratios and balance sheets.

This is quite interesting as banks are remaining resilient to the current economic situation. Not only banks benefit from higher rates, counteracting what in general may damage the economy, but also higher rates for banks mean higher earnings and therefore tighter bond credit spreads, that can help bolstering bond prices and counteract the inverse effect that higher rates normally have on fixed income products.

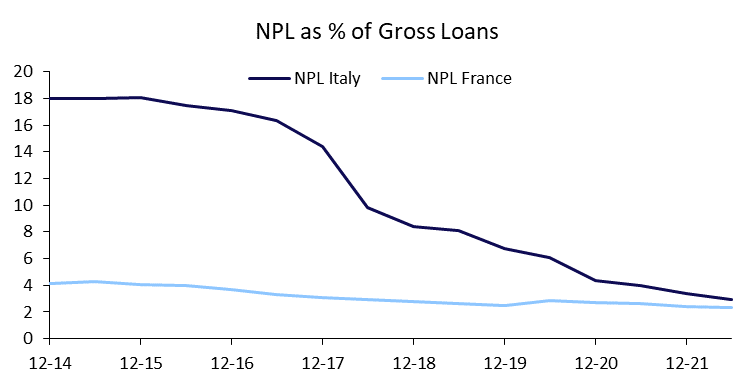

Bank solidity is further shown by the trend of Non-Performing Loans (NPL) over the last few years. The chart below shows the share of non-performing loans in Italy and France, two major European economies during the last decade.

Source: Bloomberg, Bocconi Students Investment Club

It is evident that the share of NPLs has reduced considerably since the aftermath of the 2012 crisis. Asset quality today is much stronger and has not materially deteriorated over the Covid crisis, thanks to the liquidity injections that the central banks have provided over the last few years. Banks’ balance sheets are therefore much stronger, and this should continue to give investors confidence over their capital structure and the probability of sudden insolvency events.

The main threat to our investment analysis we believe is represented by underestimating the probability or indeed the effects of a harder recessionary environment, particularly in Europe.

If this happens it is possible that the earning bonanza we have been seeing and will probably see in the next few quarters, can be offset by the effects of a hard landing affecting corporate earnings, level of activity and corporate and retail lending delinquencies.

It must be noted that the current inflation volatility and possible recession is a very different recession compared to the one we had in 2008 and 2012. Those recessions were driven by extremely hard shocks, the subprime/Lehman crisis and the subsequent Government Debt Crisis of 2012, caught the banking system in a very weak state. Here, not only, as we said, banks are much stronger and are already provisioning for potential losses, but also the recession might be caused by very high interest rates, that, as we have seen, are quite beneficial to the banks’ bottom line.

T2 Subordinated Debt Opportunities

Before taking a look at individual issuers, in the following paragraphs we analyze the performance of subordinated debt against the backdrop of geopolitical turmoil in Europe, ensuing recession fears, and the ECB’s hiking cycle.

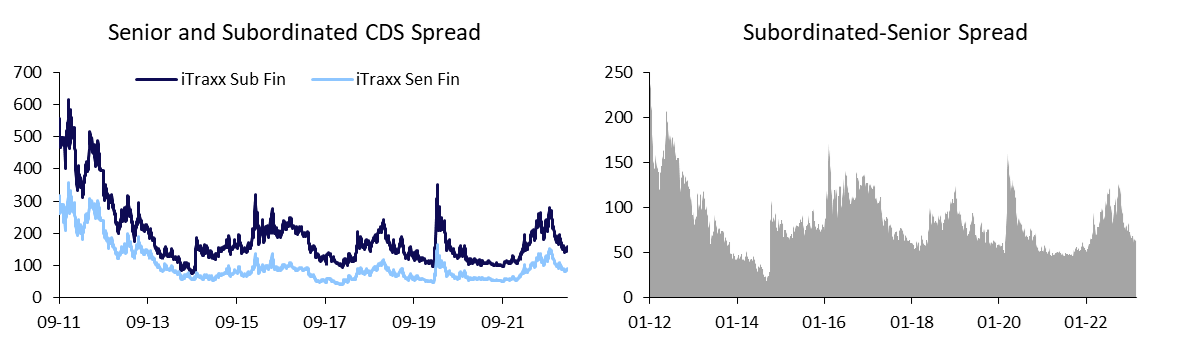

First, the charts below display the historical levels of the iTraxx Europe Subordinated and Senior Financials Indices during the last decade. The indices display the average credit spreads for a basket of subordinated and senior bonds of twenty-five financial entities that are part of the iTraxx Europe index. As is evident from the charts below, spreads on both classes tightened substantially after the peak of the European debt crisis, in line with the build-up of more resilient capital reserves by financial institutions. Over the course of last year, spreads on both senior and subordinated debt widened substantially with the beginning of Russia’s war against Ukraine. Already at the end of last year, spreads began to tighten again, as the impact of the initial economic shock waned, and investors reassessed the likelihood of a severe recession in Europe.

Source: Bloomberg, Bocconi Students Investment Club

A similar picture is apparent when considering the difference in spreads between senior and subordinated debt. From the peak of the European Debt Crisis, spreads tightened as banks’ capitalization and overall credit risk decreased. The sudden spike in the difference in October 2014 is thereby solely due to a definitional change of subordinated debt by the BIS. Since the beginning of 2022, the difference between the two baskets widened in line with historical magnitudes after the Debt Crisis by 60-80 basis points. Still, this impact is substantially below the levels observed pre-2014. As recession fears and the severity of the energy shock were reassessed over the last several months, the gap between subordinated bonds and senior debt again tightened and currently is close to pre-war levels.

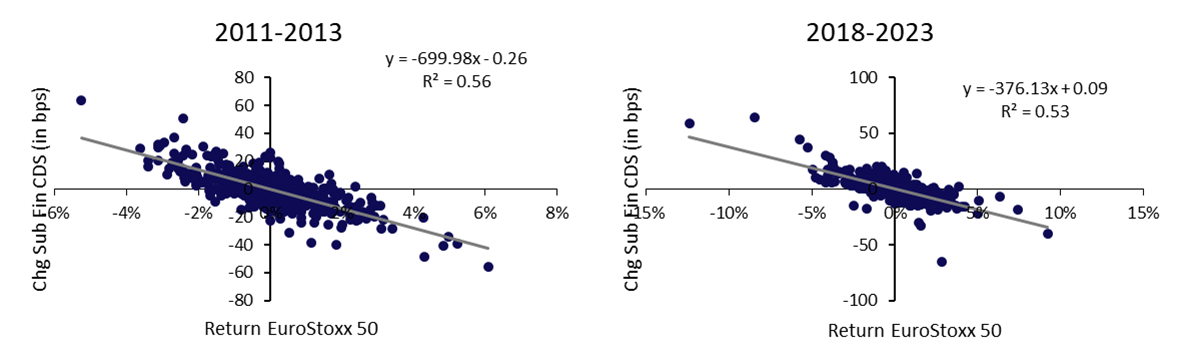

The stronger resilience of banks’ balance sheets and the resulting increased market confidence in subordinated debt is also evident from the securities sensitivity with respect to broader market sentiment.

Source: Bloomberg, Bocconi Students Investment Club

Here, the daily change in CDS levels of the iTraxx Europe Subordinated Financials Index is regressed against daily returns in the Euro Stoxx 50 Index, before and after the implementation of the large part of the Basel III regulations. The analysis points to a substantially higher sensitivity of subordinated debt credit spreads for the early sample period from 2011 to 2013. It should be noted at this point that these indices represent a basket of securities for large European issuers. The actual spread levels may substantially vary depending on the issuers credit rating, as well as the specific provision of each subordinated bond. Key factors e.g. include the trigger levels for CoCos, the schedule of call dates for callable bonds, and generally the level of subordination with respect to other claims by creditors.

As mentioned earlier in the article, banks’ solidity is much improved in comparison to the GFC levels and the years following up to the implementation of Basel III regulations. Together with the increased scrutiny of bank capitalization, record earnings deriving from a favorable interest rate environment have prepared large retail and commercial banks for a potential recessionary environment. Furthermore, the stability the spread between senior and subordinated CDS has shown is another indication of the resilience of financial institutions and investor confidence.

Relative Value Analysis

This benign environment and the similar behavior between senior and T2 bonds, lay the foundation for the argument that the premium offered by T2 bonds is very compelling when it is compared with senior debt or high yield corporates.

In order to obtain a yield in the range of 6-7% with corporate bonds, the credit ratings that the investor has to confront are of a much higher risk profile than with financial T2 debt. Furthermore, the nature of the risk is also different. T2 ratings are driven by contractual subordination only, and not by the ability to service debt the institution emitting the bonds has, hence the financial debt seems more attractive.

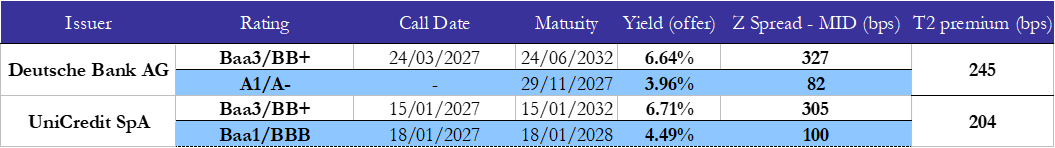

With the average spread between senior and subordinated financial debt back down to the 50-60bps level, from their recent September highs, it is compelling to look at two pairs of bonds, which still offer a much larger subordinate premium while maintaining competitive credit ratings. In the following we present two exemplary issues.

Source: Bloomberg, Bocconi Students Investment Club

Deutsche Bank’s 32NC27 offers a yield of 6.64%, 245-bps higher than a senior bond maturing on 29/11/27, with the bonds being rated Baa3 and A1 respectively. Similarly, UniCredit’s 15/01/27 offers a yield of 6.71%, which has a 204-bps premium over a senior bond maturing three days later. The credit ratings of this pair of bonds are Baa3 and Baa1 respectively. These are two strategic and systemic European institutions, which enjoy senior ratings in the strong A and strong BBB category, that are notched down only due to their contractual subordination, not their inability to service their debt obligations. The likelihood of an insolvency event for these institutions, in the next 12 months seem a remote event well remunerated by the yield and spread to senior.

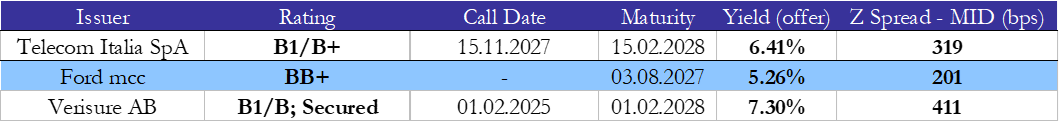

These figures become even more interesting when they are compared to other corporates that yield the same type of return. In the table we show some HY bonds and their main characteristics. Telecom Italia’s 27 bond, for example offers a comparable yield of 6.41%, but a considerably lower rating of B1. Together with the fact that the financial institutions will continue to receive adequate attention from their respective governments in case of a recession, it is visible that in order to obtain a yield in the 6-7% ballpark in the normal corporate bond market you will have to go down the actual credit scale, down to the low BB single B level.

Source: Bloomberg, Bocconi Students Investment Club

We believe investment in the two T2 bonds we have highlighted offer an attractive risk/reward balance.

Sources

Pablos Nuevo, I. (2020). Has the new bail-in framework increased the yield spread between subordinated and senior bonds? The European Journal of Finance, 26(17), 1781-1797.

Sironi, A. (2003). Testing for market discipline in the European banking industry: evidence from subordinated debt issues. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 443-472.

0 Comments