Introduction

Over the past decade, private equity firms, previously known for their aggressive takeovers of large corporations, entered the relatively somber world of insurance. Apollo Global Management [NYSE: APO], under the initiative of co-founder Marc Rowan, entered the world of insurance through building Athene. The idea was that the float of annuities, the money that policy holders have paid to the insurer to receive a constant stream of income later in life, could be invested at a higher rate than the approximately 2% p.a. required to fulfill the obligations to policy holders. This business proved to be incredibly successful, but also is now commanding the attention of regulators, who are worrying that the float is possibly invested into too risky assets, potentially exposing the insurance companies’ ability to fulfil their commitments to policyholders. To understand whether this worry is justified, we have decided to look at the space in a more in-depth fashion.

An Introduction to Annuities

The idea behind an annuity in an insurance context is straightforward: it offers a consistent flow of income for a predetermined amount of time, typically for the rest of one’s life. Payments can be made as a flat sum or spread out over time, and are typically acquired through an insurance provider. Fixed annuities, a product category from which some traditional life insurers have been migrating away from towards more variable annuities due to persistently low interest rates, have been of particular interest to private equity firms. The amount of money paid out by the annuity each year is predetermined and not subject to market swings because they promise a fixed rate of return for a given period. While the recent pull-back by life insurers from the annuity business is largely just a reaction to historically low-interest rates, which have made it difficult to turn a profit on some long-standing life insurance offerings, there is an underlying trend that the rates that were promised to contract holders in the past were frequently more generous than those currently on the market. When interest rates are low, insurance companies typically reduce the rates on their fixed annuities, as they cannot offer the same level of return without taking on more risk.

This is an opportunity in the eyes of private equity and other investment companies. Customers purchase fixed annuities in lump sums, and the insurer invests the funds intending to outpace the interest and principal payments that must be made. To manage these specialized assets and generate fees, private equity companies invest the lump sums in debt categories that they are knowledgeable about (which is why firms which traditionally invest in complex credit products tend to be the largest buyers, as that is the edge). Annuity contracts typically guarantee customers a return of about 2% to 3% annually, but a savvy credit investor like Apollo, KKR [NYSE: KKR], or Blackstone [NYSE: BX] might be able to add up to 4% on top of that, making the same assets more lucrative to private equity firms than their typical life insurance competitors. Private investment in insurance products is nothing new. Although Berkshire Hathaway’s acquisition of National Indemnity, a speciality and property and casual (P&C) insurance company, in the 1960s is where McKinsey places the trend’s beginning, the top buyers have now become PE funds. Private equity has formed alliances with insurers over the past ten years to benefit from their substantial “floats” (the money to be invested between customers paying premiums and when they make claims on their policies). Apollo, which founded the annuity business Athene in 2012, set the standard for this trend.

Source: Financial Times

Some PE firms invest directly into life insurance or annuity businesses, but more recently, deals to handle the assets of insurance companies were made by Blackstone, Carlyle, and others from their balance sheets separately from any fund, only further reenfocing their convictions regarding the high growth nature of the utilization of “float”. Recent transactions in 2022 include Blackstone’s acquisition of Allstate Life Insurance Company for $2.8bn, which represents 80% of Allstate Corporation’s life insurance and annuity assets (roughly $23bn), and KKR’s acquisition of a 60% stake in insurer Global Atlantic in which more than 2m clients have fixed annuities, life insurance, and other policies, for more than $4bn in February, adding $90bn in assets under management.

26North, the newest endeavour of Joshua Harris, a co-founder of Apollo, only reinforces this. With $9.5bn in AUM, an emphasis on private equity, credit, and insurance solutions to drive returns, as well as a strategic partnership with American Equity [NYSE: AEL], a top provider of fixed-income annuities, the company serves as an even better indicator of the direction the private equity sector is heading towards overall. Athene is responsible for more than half of the $523bn that Harris’ prior company, Apollo, has under management, only further highlighting permanent capital’s permanent place on PE firm’s books.

Risks Posed by Financial Sponsors in Insurance

Life insurance companies have historically invested in publicly traded stocks and high-grade bonds characterized by low-risk profiles and high liquidity. They could easily be sold whenever insurance companies needed cash to meet their policyholders’ requests. However, the low interest rate environment witnessed over the last decade led to low bond yields and, as a result, low returns. Because of this, several insurance companies agreed to partner with private equity firms that introduced them to riskier investments characterized by higher returns. Today, despite the significant increases in interest rates, bond yields remain low by historical standards and, therefore, private equity-owned insurance companies keep seeking higher relative yields by investing in riskier assets, like private debt and equity. Their investments include structured securities, such as collateralized bond obligations (CLOs), and esoteric credit instruments linked to residential mortgages, corporate debt, equipment leasing and shares in private equity. For example, investments by insurers in private equity funds increased from $58.7bn in 2016 to $117.4bn in 2021. These assets are not only riskier but also illiquid. This means that if cash is suddenly required to satisfy a spike in demand for payouts, like during a recession, these investments might be challenging to be converted into cash.

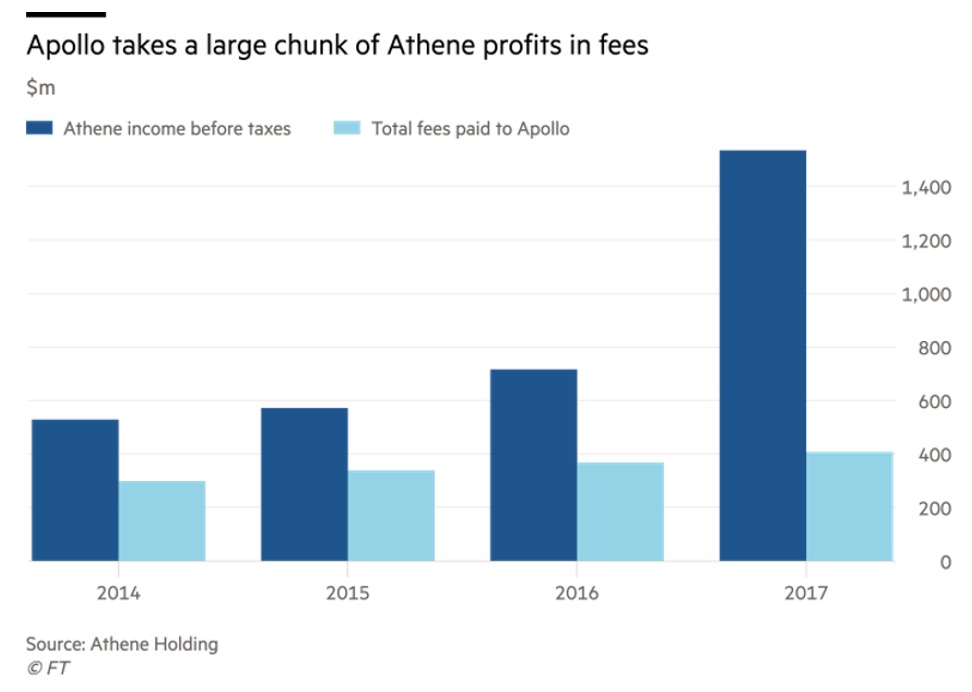

The illiquidity and risky nature of the investments are not the only concerns related to private equity-managed insurance companies. These private equity firms might act in their own interests, disregarding what is best for insurance companies’ shareholders and policyholders. For example, Apollo, according to its contract with Athene, charges considerably high fees for managing the insurer’s portfolio. Interestingly, even some Apollo insiders argued that Athene could save hundreds of millions of dollars annually if it replaced the private equity firm with an independent asset manager.

Source: Financial Times

Private equity firms might also encounter significant conflicts of interest. Some of them use insurance assets to invest in high-fee alternative investments including their own buyout, real estate, and debt funds. This raises the question of whether these firms are engaged in self-dealing due to the current absence of regulatory oversight. The main concern that has been raised is that they might use the insurance assets to strengthen the performance of their struggling funds even when they are not the best investment option for the insurance company. Moreover, the claim that risky alternative strategies will benefit policyholders might fail. Not only are their savings exposed to additional risk, but the high fees charged for managing these complex instruments might erode the high returns associated with greater risk. For policyholders who bought annuities from insurance companies that were making plain vanilla investments, it might be disconcerting to learn that their policy has been sold to a private equity firm that will be making risky investments with a portion of their retirement savings.

Another concern is that these private equity firms are engaging in regulatory arbitrage as they are circumventing regulations by taking advantage of regulatory gaps in the system. One common practice is using minority stake holdings in insurance companies to avoid the strict laws that heavily regulate the industry and the oversight that these would bring. For example, before completing the merger with Athene in 2022, Apollo only held a 10% stake of the insurance company but was already managing its assets. Furthermore, while the SEC and other federal financial regulators monitor fragments of the private equity industry, insurance is regulated at the state level. Also, although the private equity interest in insurance started over a decade ago, state insurance commissioners have done little to mitigate the potential risks. Senator Sherrod Brown, US Chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, is pushing regulators to investigate the “increased risk-taking behaviour across the life insurance industry, which could contribute to increased systemic risk across the financial system”. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) outlined a list of concerns about private equity-owned insurance companies, but it has not taken any legal action yet.

Regulating private equity firms is challenging because there is only little reliable information about their practices, making it difficult to measure the risk and returns policyholders are exposed to. It is, however, clear that they are engaging in less transparent and more difficult-to-trade investments that might be difficult to sell to meet annuity obligations. The Federal Reserve has expressed concerns that investments in difficult-to-sell debt and equity holdings may mean that insurers will lack the cash to pay a surge of claims in an economic crisis. Not only do the assets lack liquidity, but they might also decrease in value in such circumstances. What is important for insurers to protect themselves and their client is to clearly understand their holdings, which requires absolute transparency of the underlying assets contained within the private funds. Access to clean and harmonized data is, in fact, essential to avoid any unexpected liquidity or net-asset-value issues, which are more common in private funds than in more traditional asset classes.

Many of the risks and concerns mentioned resemble the 2008 financial crisis and what triggered it. In 2008 excessive risk-taking by global financial institutions and wrongly graded mortgage-backed securities led to the Great Recession, costing many their jobs, savings, and homes. Today, insurance companies and pension funds bear an enormous burden on society as they are responsible for people’s retirements and life savings, and this requires them to be conscious of their decisions and investments. They must be able to evaluate all their assets, private-market ones included, in a centralized place to manage risk and performance. Only then can they ensure that private funds are incorporated safely into their investing strategies without endangering millions of people’s savings.

Conclusion

The question of whether the risks taken by the insurance arms of alternative asset managers are excessive is ultimately something that can only be answered by the passing of time. Apollo and its peers naturally argue that, due to their high level of sofistication, they are uniquely able to invest at high returns but still low risk. However, the last time returns appeared to diverge from risk, the great financial showed us that the two remain strongly correlated. In order to prevent re-learning that lesson through a painful and expensive crisis, we can imagine that government regulation will somewhat curtail PE-backed insurers’ risk taking. On the other hand, this regulation may never be implemented, as it will be difficult to pass such reform when you are fighting against an industry that pays top dollar for the most influencial lobbiests across the world.

0 Comments