Introduction

In 2010, it was a head-scratcher as to why FIFA would pick Qatar as the 2022 World Cup host. A single football stadium, scorching heat, and a national team ranked 96th in the FIFA world ranking. FIFA’s own technical committee rated it the worst of all bids made to host the cup. A decade later, Qatar has reportedly spent over $229bn preparing for the tournament, undertaking massive infrastructure projects in due time. But behind the glitz and celebrity endorsements of this first World Cup in the Middle East, lie accusations of corruption and human rights abuse.

Before looking at who built what in terms of the infrastructure, we will dive into FIFA’s role in organising the World Cup. Then, we will outline FIFA’s business model and imagine the cup’s impact on Qatar and the world for the following years.

The Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA)

The Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) is the governing body of world football in charge of organising many of the sport’s international tournaments. Created in 1904 to provide a single body to oversee the discipline as it grew in popularity in the 20th century, it is headquartered in Zürich and it comprises 211 national football associations (FAs). The World Cup represents 95% of FIFA’s revenues. Being a non-profit association, it reinvests the billions it makes every year back into the sport, by financing and even operating football facilities. Still, FIFA today faces heavy scrutiny after an investigation in 2015 brought forward allegations of corruption and bribery against 41 of the highest-ranked FIFA officials, government leaders, and corporate executives for being involved in a “24-year scheme to enrich themselves through the corruption of international football”.

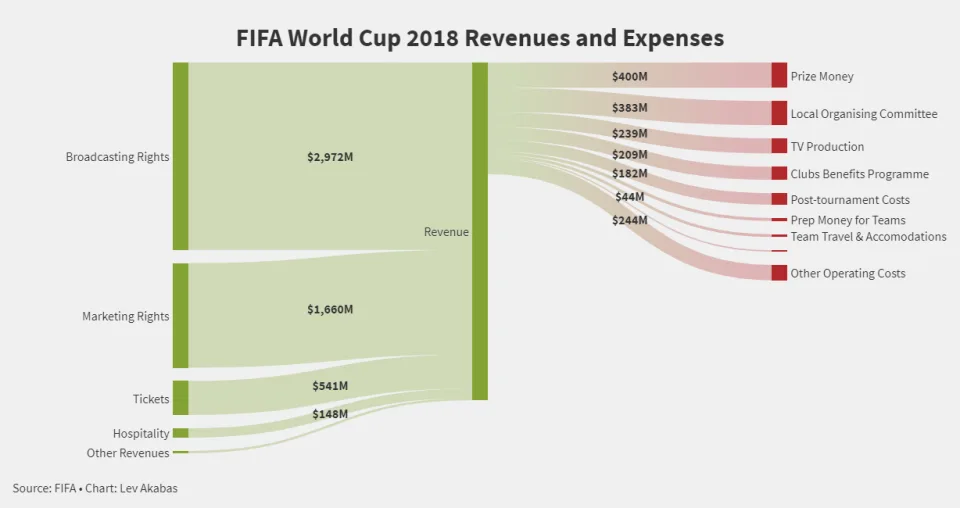

Remarkably, FIFA manages to rake in substantial earnings and incur very few expenses thanks to the World Cups. Considering that FIFA earns 95% of its revenues through the organisation of the World Cups, the following graph provides an in-depth overview of the association’s revenues and expenses. In fact, it also explains why FIFA is pushing for a biennial World Cup.

Source: FIFA & Lev Akabas

Over twenty years, World Cup revenues have been multiplied by a factor of four. FIFA sells broadcasting rights (60% of revenues) to television stations and broadcasting institutions, permitting them to broadcast football games and related events in particular regions. Because football is immensely popular, competition among broadcasters for licensing rights is fierce. Surprisingly, marketing rights (25% of revenues) haven’t suffered much because of the 2015 corruption scandal involving high-level FIFA officials and Russia’s and Qatar’s successful bids.

The spending on advertising and marketing for 2022 is set to hit a record high since it is in the run-up to Christmas and New Year, giving Qatar the potential to provide a unique experience for brands. Hospitality packages are basically individual tickets paired with catering services and dedicated areas. FIFA expects $4.7bn in revenues from the Qatar World Cup according to its 2022 budget. TV broadcast rights will account for $2.64bn and marketing rights for another $1.35bn, while ticket sales and hospitality rights should add up to $500m.

In terms of expenses, FIFA pays the prize money to the participating nations, accounts for the travel and accommodation of players and supports staff and match officials. Also, it makes a FIFA World Cup legacy fund available to the host country to be used in future for the development of the game in the host country. But since infrastructure costs are left up to hosts, FIFA’s expenses remain relatively low.

Qatar’s Bid

How did this tiny country manage to pull off one of the most extensive World Cup bids in history? Considering its 2010 population was not even over one million, how could it ever accommodate a million and a half visitors over a one-month period? And how could players perform in temperatures often reaching fourty degrees in summer?

Let’s look at the World Cup bidding process. Usually, seven years before the competition, FIFA will invite its member nations to bid. These nations have four years to discuss the opportunity and apply. All interested parties are sent an application pack, which includes the expected criteria, investment and stadia required: the nations’ governments and FAs work together to fulfil FIFA’s requirements. From this point on, nations have one year to finalise the bid by completing objectives, including setting out what investment will be required (number of stadiums for example, and the deadlines). Once this is done, FIFA embarks on a series of four-day tours of each of the prospective hosts to visit the venues and potential sites.

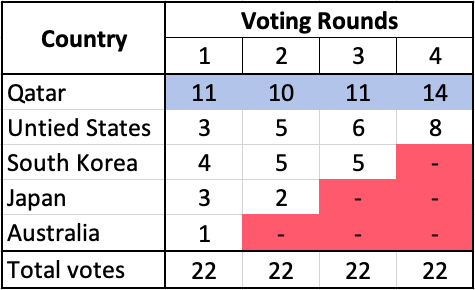

The location is chosen by the members of the FIFA Council, the main decision-making body of the organisation. It’s composed of 37 members: a President, elected by the FIFA Congress; eight vice presidents, and 28 other members elected by the member associations – each for a term of four years. In 2010, there were only 24 eligible voters, two of which were prevented from voting because they had been filmed selling their votes.

In each round, a majority of twelve votes was needed. If no bid received 12 votes in a round, the bid with the fewest votes in that round was eliminated. In the end, Qatar won with the American bid by a difference of six votes: fourteen to eight.

Source: BSIC

So how did Qatar come out on top of the US, South Korea, Japan, and Australia? The reason most put forward by FIFA was the importance of finally hosting a World Cup in the Middle East. Qatar promoted this edition of the World Cup as an Arab unity bid and an opportunity to bridge the gap between the Arab and Western worlds. In fact, this allowed FIFA to grow in influence and make substantial investments in the region.

Yet, this is far from enough to explain how this absolute monarchy came out on top. In fact, we just mentioned another unofficial reason: FIFA finds absolute monarchies and oligarchies easier to deal with than Western-style democracies, whose due process and debate lead to slower decision-making. In fact, one of FIFA’s ex-Secretary Generals said that “less democracy is sometimes better for organising a World Cup […]. When you have a very strong head of state who can decide, as maybe Putin can do in 2018… that is easier for us organisers than a country such as Germany, where you have to negotiate at different levels”.

So, it is also about politics. Another element that epitomises this is Qatar’s influence in France with Platini, a French ex-football star on the FIFA Council at the time. It was revealed, after the vote, that he had been invited to the Champs-Elysees, to meet the then-President Nicolas Sarkozy. Platini entered the room where the Emir of Qatar, Hamad ben Khalifa Al Thani, had been dining with Sarkozy. They had just negotiated a deal not only for the country to buy France’s military jets, but also to buy the Paris football club, Paris Saint-Germain, and to buy the broadcasting rights to France’s football league. Qatar injected massive amounts of capital into France, and its President made it very clear to Platini on who he should be voting. Sepp Blatter, ex FIFA-President, said that “thanks to the four votes of Platini and his [UEFA] team, the World Cup went to Qatar rather than the United States”.

An even darker side are the numerous allegations of bribes that have been investigated for more than a full decade. Sepp Blatter publicly confirmed that Qatar and Spain and Portugal had colluded to trade votes for their respective 2018 and 2022 World Cup bids. Two years ago, The United States indicted three South American FIFA officials for having received payments to vote for Qatar. Two of them had already died, and the third, Ricardo Teixeira, the former Brazilian FA member, remains in that country since it does not have an extradition treaty with the US. Qatar’s Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy rejected the charges and has stood ground ever since. Out of the 24 members of the 2010 FIFA Council who voted to choose Qatar, 9 have since then been banned from the Council by FIFA itself for fraud and bribes.

In terms of the lacking sports and accommodations infrastructure, Qatar pledged sizeable investments and undertook ambitious infrastructure projects: It is estimated that it had invested $229bn over the last twelve years in the run up to the World Cup. That is 16 times more than what Russia spent in 2018, which at the time was the most expensive World Cup ever. $229bn is also more than twice the money spent on the eight past editions of the World Cup, combined.

Infrastructure

Qatar undertook a myriad of infrastructure projects to fill in the gaps: stadiums, a metropolitan network built from scratch, hotels to accommodate the million and a half of expected visitors, upgraded roadways and railways and even built a new city. Since the World Cup is also meant to serve as an engine to push forward and accelerate a lot of the initiatives that the Qatari government had already committed to, it has financed all these projects from its own budget. In comparison, Russia spent less than $15bn, and the biggest line items included transport infrastructure ($6.11bn), stadium construction ($3.45bn) and accommodation ($680m).

The Qatari state has built seven new stadiums, and fully refurbished the sole stadium it had before winning the bid. As part of its application pack, Qatar promised that after the event, sections of the stadiums would be deconstructed and donated to other countries, and that the buildings would be repurposed into community space for schools, shops, cafes, sporting facilities and health clinics. One of the venues, Stadium 974, was built using recycled shipping containers and will be entirely dismantled and removed. The cost of construction is not known, but the estimates indicate a range between $6.5bn and $10bn. A major expense were the cooling systems that were added to all but one stadium. This roughly tripled construction costs at Al Janoub Stadium, which was among the first to be completed. The country sourced its grass from the US (Georgia) and grew it in massive nurseries.

European firms have been involved in the constructions process, too. The British Department for International Trade helped British companies secure between £940m and £1.44bn in Qatar World Cup-related exports, especially related to stadium building. Belgian construction group, Besix, was also involved in the renovation of the Khalifa International Stadium and the construction of the Al Janoub Stadium. Both projects are led for Besix by Six Construct, the entity it founded in 1967 for its activities in the Middle East.

Also, the construction of sufficient accommodation that would hold 1.5 million visitors, was an extensive undertaking. Qatar’s small size has posed a challenge for organisers, who have turned to non-traditional measures including cruise ships, desert camps and serviced apartments. The plan is for 130,000 rooms to be available, but many hotels haven’t been completed in time for kick-off. Government spending also includes about $45bn for the construction of Lusail, a mega-development north of central Doha, which as only in 2010 had still been a desert. It will ultimately be home to about 200,000 people, according to its developer. Dutch firms, including the construction giant BAM Dutch, and the steel company Frijns Staal, have capitalised on this opportunity, each winning contracts worth around $10m.

In terms of transport, this is where Qatar took it to a new scale. Its long-term goal was to become more of a transport hub for a significant portion of the globe. The top priorities included the development of airports, as well as a more extensive metropolitan network, along with upgraded roadways.

Since most fans are arriving by air, it was essential that for the Hamad International Airport (HIA) to undergo expansion. Inaugurated just a month before kick-off, the airport’s Phase A expansion increased HIA’s capacity to over 58 million passengers per annum. HIA has also temporarily reopened a refurbished Doha International Airport (DIA), which ceased operations for commercial flights in 2014 when HIA was opened, to help cater to the massive influx of visitors to the country. Thirteen airlines will operate to and from DIA, in addition to charter flights.

According to Qatar’s Public Works authority, the country also quadrupled the road network from 490km in 2013, added more than 2,000km of cycle paths and increased its number of bridges tenfold from 22 in 2013. Another literally ground-breaking enterprise was that of the metropolitan and railway network built from scratch. The three-line tub spans thirty-seven stations and set a world record for the largest number of tunnel boring machines operating simultaneously during a single project. Dutch companies were also involved in the construction: Royal Haskoning DHV drew up the master plan and engineers from the firm Arcadis designed several of the subway stations. Mijksenaar, which operates in the visual information systems industry, was responsible for the signage in all subway stations.

Source: Google Earth Image – Imagery ©2022 CNES / Airbus, Landsat / Copernicus, Maxar Technologies, US Geological Survey, Map data ©2022

Qatar’s population was not large enough to supply enough workers to build the infrastructure for the games. It turned to hundreds of thousands of migrant workers, mostly from India, Nepal and Bangladesh. Just to secure a job, migrants had little choice but to pay recruitment fees of up to $4,000 before they left. Once they got to Qatar, they were already in debt and trapped in the system known in the Middle East as “kafala”, a form of modern-day slavery (passport confiscation, cracking down workers trying to strike, wage cheating). It meant workers visas were sponsored by employers who had a complete control not only over their job, but also their immigration status.

Qatar claims it got rid of the kafala system in 2016, but human rights groups claim it never really went away. Between 2010 and 2022, 6,500 migrant worker deaths have been alleged, but Qatari authorities registered 70% of these as natural deaths, refusing to conduct autopsies. Under pressure from human rights groups, Qatar had shut down more than 300 labour sites in 2019 and introduced new guidelines. Around a year later, workers were granted the freedom to leave the country without an exit permit and change jobs without their employer’s consent. In May 2022, human rights groups called on FIFA to create a compensation fund for migrant workers that equals the World Cup prize money pool of $440m dollars.

FIFA Sponsorship Model

FIFA’s sponsorship model divided its partners into three distinct tiers: FIFA Partners, FIFA World Cup Sponsors and Regional Sponsors. Due to the organisation’s global profile, but primarily thanks to football’s popularity across the globe, biggest companies worldwide have sponsored the World Cups. Household names such as Adidas, Coca-Cola, Qatar Airways and Visa are all part of the FIFA Partner tier. It allows these companies to market their product offer and always use the association’s branding, regardless of whether a tournament is happening. Currently, FIFA allows for 6 to 8 Partner slots.

The second tier, World Cup Sponsors, include companies paying for rights to present their branding or products only in the build up to, and during the tournament itself. These companies include Mc Donald’s, crypto.com, Hisense and Budweiser. Concerning the latter, it was a subject of a hassle between FIFA and Qatar’s regulators due to the strict anti-alcohol consumption laws present in the Middle Easter country. Despite an agreement in place for the American beer-maker to sell alcohol outside stadiums during games, two days before the World Cup’s inauguration Qatari’s Emir personally intervened and reneged on the deal. It is one of the most fascinating corporate-stories related to this year’s tournament, underscoring how significant influence Qatar exerts over the football’s global governing body. Budweiser, who had paid around $75m to become the exclusive alcohol-distributor during the tournament, was restricted to only selling its products in the official fan-zones scattered across Qatar. While it is likely that the American company, owned by the global beverage behemoth Ab InBev, will sue FIFA for breach of contract, it has meanwhile announced that the unused beer will be awarded to the winner of this year’s tournament.

The lowest tier in FIFA’s sponsor pyramid are the regional sponsors, selected according to geographical origin. There is a limit of four companies per each of the five designated regions. Companies participating in this tier enjoy the same rights as the ones constituting the World Cup Sponsors list.

Despite raking in more than $1.3bn in sponsorship/marketing income during this year’s World Cup, FIFA is discussing potential changes to its sponsorship tier structure. With the rise in popularity of women’s football, as well as e-sports, FIFA will likely separate men’s football from the former. The additional, fourth tier, is set to give the participants rights to access all tournaments organised under FIFA’s auspices. Arguably, the move will also make it easier for the organisation to invite more sponsors in the light of the already confirmed expansion of the men’s World Cup, to 48 teams. With regions such as Asia given four more spots at the tournament, it is arguably an excellent opportunity to further increase the revenue base and capitalise on the splurging growth of the developing economies around the world.

Conclusion

No event will likely dissipate the intensity of criticism that both FIFA and Qatar have faced in the run-up to this year’s World Cup. And while FIFA’s proneness to corruption and scandals and Qatar’s negligence of its migrant workers should be ostracized and ridiculed, it cannot escape our minds that the region and country itself should not. If anything, the tournament should serve as a binding moment to the Middle East and further encouragement to the idea of respecting contract commitments and basic human rights as these do not distinct on race and culture.

0 Comments