Football industry overview

During the last couple of decades, football became a huge industry within the overall sports space. Ever-growing revenues of football clubs coming from advertising, broadcasting rights, and merchandising result in stellar salaries and exponentially rising transfer market prices, as such spending is considered as almost unavoidable by the best clubs to remain at the top. Consequently, large sums in the football industry became attractive for various groups of investors, and in this article we will explain how the modern football industry works and how it came to the idea of the creation of the Super League, even though it has not gone through.

Publicly traded clubs

The logical place to start is the stock market. Today there are only 11 listed clubs in the major leagues, and interestingly most of them currently trade below their IPO prices. One of the potential reasons behind such underperformance of football clubs’ stocks is the high unpredictability of performance on the field in the long run. This unpredictability stems from the fact that single players or coaches have a great influence on the team’s results, a good example of it being Manchester United. After Sir Alex Ferguson left the club as a coach it started struggling, even though before it was highly successful for many years. However, even constant sporting success might be not enough for the stock price to rise, as shown by Juventus that is winning Serie A every season since 2011-2012, yet its stock price remains stable for most of the last decade at a level lower than the IPO price. Another major issue affecting the share price is excessive debt-taking to sign the best players, which without being associated with solid free cash flows makes investors cautious about the stock.

Private ownership structures

As mentioned before, there are only a handful of publicly traded football clubs, and thus private ownership is the most common type of ownership existing in the European football industry. Across the continent’s top 5 leagues – England’s Premier League, France’s Ligue 1, Germany’s Bundesliga, Italy’s Serie A, and Spain’s La Liga – 87% of the clubs are privately owned. However, with a significant inflow of capital into the industry, the nature of private ownership experienced a pronounced transformation in the last two decades.

Thanks to the ever-increasing digitalization of services, the world’s most popular sport was able to reach previously unattainable fans and audiences. By virtue of the internet and TV, supporters from Africa, the Americas, or Asia could easily tune in and watch their favorite team from thousands of kilometers away. With the rise of global audiences, the market became increasingly more attractive to broadcasters and advertisers. Only between 2010 and 2020, the revenues of clubs from the top 5 leagues more than tripled – from €7.9bn to €28.9bn.

With that, also private ownership underwent a profound change. Starting from the English Premier League, numerous high net-worth individuals and sports management entities began acquiring majority stakes in clubs. Having taken over Chelsea in 2003, the Russian Israeli oligarch, Roman Abramovich, initiated a trend. The Glazer family bought Manchester United in 2005, Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed invested into Manchester City, and American sports mogul, Stan Kroenke, bought into Arsenal in 2011. Since then, similar moves happened across the continent – Qatari 2011 takeover of France’s PSG, or the 2016 purchase of Inter Milan by a Chinese retail conglomerate, Suning.

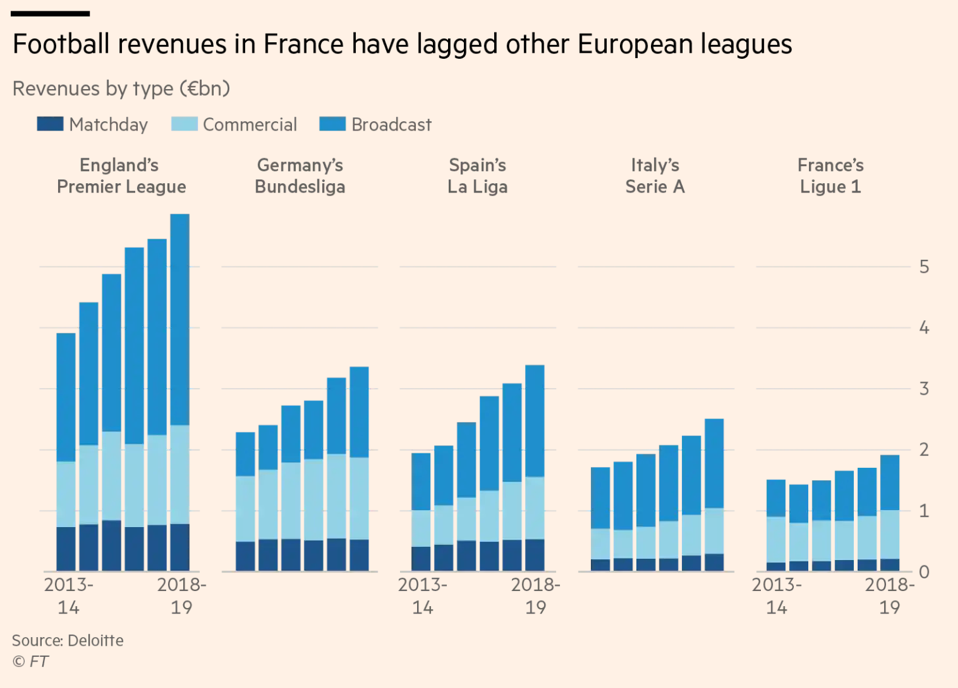

Yet, it is England that is the trend’s unquestionable champion. Arguably, this is due to the €1.9bn in TV rights granted every year between 2019-22 – more than any other European league has ever received. As a result, English clubs outpaced their peers in terms of revenue growth, but also attracted heavy criticism for leaving the fans out of the bargain.

Source: Financial Times

However, not every country followed the steps of English clubs. Germany is the most prominent example of regulations aimed at ensuring fans retain the majority control over their clubs. The “50+1” rule regulates that 50% of shares + 1 share are in the hands of supporters or fan organizations. It is supposed to limit investors’ ability to decide on important matters (e.g. increasing ticket prices) without the fans’ approval. Arguably, the lack of similar regulations enabled owners of Premier League clubs to disproportionately increase the prices of season tickets. The cheapest season pass amount to £500, whereas Real Madrid or FC Barcelona, top Spanish clubs, price them at only £200. Also, arguably, it was the “50+1” that caused German powerhouses, including Borussia Dortmund and Bayern Munich, to stay away from the European Super League.

Yet, it still does not avert controversies. RB Leipzig, promoted to the Bundesliga in 2016 and owned by Red Bull, circumvented the regulations by granting membership to only a handful of “fans” – most of whom were directly connected to Red Bull. Many voices question the rule – yet in 2009, 32 out of 36 German first and second-tier clubs voted against abolishing it.

Also, Spain has its form of fan control – the “socios” ownership structure. By law, most Spanish clubs are required to have private owners. However, due to historical and societal heritage, 4 clubs – Athletic Bilbao, FC Barcelona, Real Madrid, and Osasuna – have been allowed to adopt the “socios” model.

It relies on members of the club electing its president and directors. It may be tempting to appraise the model wholeheartedly, especially when comparing it to the hawkish, commercially focused approach of the English clubs. However, leaving business decisions to an inexperienced group of fans often leads to irrational and unprofitable choices. Most recently, FC Barcelona’s former president, Josep Maria Bartomeu, was accused of misusing the club’s funds on a social media campaign aimed at criticizing Barcelona’s players. Besides, swap deals of Arthur – Pjanic and Cillessen – Neto that was used by Barcelona not because of sporting reasons but for the sake of “creative accounting” that was necessary for Bartomeu to claim better financial results also show that the system is far from being ideal.

The case of Florentino Perez, Real Madrid’s president and construction mogul, only adds insult to injury. Elected by the socios, he was the mastermind behind the now abandoned Super League, which triggered a backlash from football fans around the world. Hence, it is easy to see that neither ownership structure is foolproof. Unsurprisingly, at the end of the day club presidents and owners predominantly care about guaranteeing constant revenue streams and steady growth. Not the most romantic vision of football, but impossible to ignore.

The capital bump in the road

Notwithstanding the differences in ownership structures, most of the top clubs in Europe share a common problem – profitability. The pandemic has only exacerbated the issue and exposed the fragility of the industry’s current business model. According to the aforementioned Perez, Real Madrid alone faces around €400m revenue shortfall. Further, in the 2019-20 season, the 12 founding clubs of the Super League recorded a £1.2bn loss, excluding player sales. Bearing in mind it was the pre-pandemic season, the loss for the current season will be even bigger.

Arguably, the reason for that is the ballooning of capital inflows resulting from the sale of broadcasting rights. With matchday and commercial revenues remaining relatively stable between 2013-14 and 2018-19 seasons, clubs’ reliance on TV money increased disproportionately. English Premier League signed a contract worth €1.9bn per season, Bundesliga €1.14bn, and Spain’s La Liga €1.14bn. These deals immensely propelled the growth of these clubs and allowed them to take even more debt – Real Madrid has around €800m of outstanding loans on its balance sheet. Transfers such as Eden Hazard’s move to Real for £103m or Coutinho’s move to Barcelona for €130m were all possible due to broadcast rights and debt.

However, when the pandemic came, the business model began to be ever more strained. Losses compounded onto the clubs, threatening their survival and long-term prospects. In France, Mediapro, a Spanish media company, defaulted on its deal in which it agreed to pay French clubs €780m per season, pushing Ligue 1 to take €112m in emergency loans. In Italy, a row over potential involvement of CVC and Advent International, top private equity firms, in a new company governing broadcasting rights led to calls for Serie A’s president to resign. It is clear that guaranteeing steady revenue streams, and control over them, has become the most pressing issue across the European football industry.

Financials in top 5 leagues

Arguably, this financial instability is the main reason behind the idea of the European Super League. Had it been enacted, the founding clubs would have netted €200-300m in a “welcome grant” alone. The league itself had been projected to bring €4bn in annual revenues – double the amount brought in by Champions League. However, before diving into the discussion of the Super League an overview of European leagues’ financial health would be helpful.

Covid-19 had a great impact on the football industry with the full lockdown in the first months and almost no stadium fans later. The clubs that have suffered the most are those from smaller countries that are more dependent on matchday revenues. The top 5 leagues, instead, after an initially difficult period, are in the process of a V-Shaped recovery.

In England, broadcast revenues over the next three years are expected to be around 8% higher compared to the last three years, thanks to the increasing growth in the international market and the involvement of Amazon that acquired two games per week through each season from 2019/2020 to 2023/2024. In Spain, the goal of “La Liga” is to try to bridge the gap between teams to increase competition and the league’s attractiveness in the foreign market. In Italy Serie A is currently assessing its options, which may include accessing private equity investment and the creation of a “Serie A” television platform in partnership with a third party.

The top 5 leagues generated aggregated operating profits of €1.4bn for the 2018/19 season, an increase of 7% on the prior year. However, there are clear discrepancies between different countries. England and Italy in the past years have not recorded great results. In England 2018/2019 saw a decline in overall operating profit to €934m from the last year as wages and other operating costs grew faster than revenue. In Italy, in 2018/2019 there was an operating loss of €36m, despite revenue growth, because of the massive increase in wage spending. On the other hand, in Spain, no club of La Liga registered a loss, which happened for the first time. This is a great result that derives from the league’s regulatory environment. In Germany, clubs achieved a league record-high operating profit of almost €400m.

Super League’s emergence and sunset

Now, with a better understanding of the finances of the top 5 leagues, it is time to discuss Super League. The concept of Super League included 15 founding clubs that were set to participate in the tournament every year, no matter what their results are, and 5 other clubs, joining the tournament based on qualification. The motivation behind this initiative was to try to make the most of the market power of the most prominent clubs in the world by directly sharing revenues and not managing them with the help of an organization like UEFA or FIFA. Investment bank J.P. Morgan has been involved as a source of funding for the new competition. With initial funding of $4bn, that would simply take away $800m in management expenses including a small portion directed at other existing competitions, and every founding club would make between $100-350m regardless of the outcome. In Champions League the maximum revenue that a team gets in the case of victory in the tournament is $100m, and thus Super League’s attractiveness for the founding clubs was visible. However, the reaction of UEFA and fans around the world was strongly negative, J.P. Morgan decided to come out of the sponsorship agreement, and thus Super League became another dream that did not come into reality. However, until the money dilemma holds and a handful of clubs possess most of the resources, popularity, and, subsequently, bargaining power, expect new “Super League’s” to come knocking on your door.

0 Comments