What is an emerging market?

The term “emerging market” was first coined by Antoine Van Agtmael, a former economist at the International Finance Corporation, in the early 1980s. At the time, Van Agtmael was working on a project to identify new investment opportunities for the IFC, which was the private-sector arm of the World Bank. Motivated by the positive results, he realised there was a strong case for foreign investment and suggested setting up a “Third World Equity Fund”. The name, however, raised eyebrows as it was not only derogatory to the countries involved but also off-putting for investors. This was when Antoine Van Agtmael proposed the more approbative term “emerging markets”, a label associated with “progress, uplift and dynamism” rather than poverty and gloom. He aimed to lift a group of promising stock markets from obscurity and consequently attract the foreign investment needed to drive development and economic growth. Although the Agtmael concept does not offer a precise definition, the term has proved to be vastly popular amongst investors and policymakers.

Fast-forward to the present day and “emerging markets” refers to markets that are in the transitional phase between developing and developed and typically possess some, but not all, of the characteristics of a developed market. Emerging markets are primarily branded by rapid economic growth accompanied by high growth potential for the future and are often still in the process of industrialisation and urbanisation. This can be due to a plethora of reasons, from favourable demographics to natural resource endowments and pro-growth policies. What differentiates them from developed markets is the fact that they typically have a much lower GDP per capita as well as other development indices such as the Human Development Index (HDI).

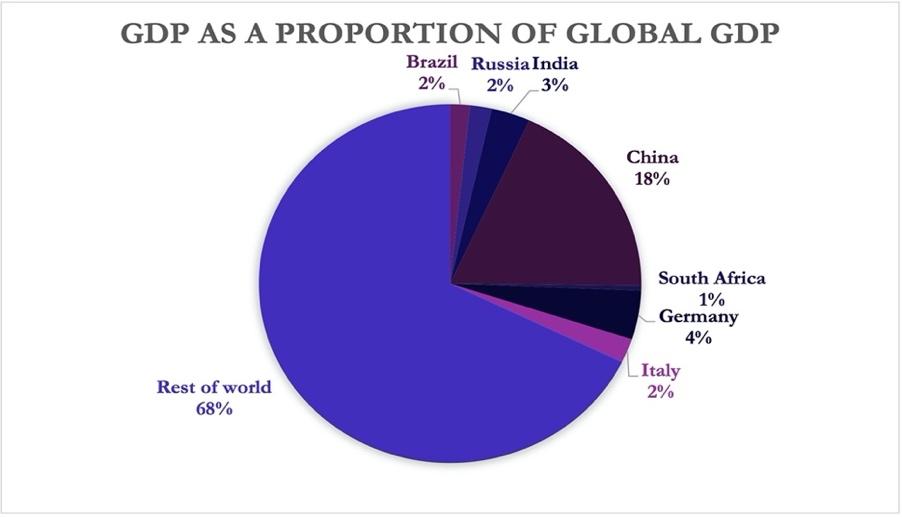

Some of the most well-known emerging markets include Brazil, Russia, India, China and South America, often referred to as the ‘BRICS’ countries. The BRICS were initially selected in 2001 by Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill as fast-growing economies that would dominate the world by 2050 and highlight investment opportunities in such regions. All five nations are members of the G20 and collectively account for 32.1% of world’s gross domestic product based on purchasing power parity. According to GDP, geographical area, and population, Brazil, Russia, India, and China are among the ten largest economies in the world; the latter three are frequently referred to as present or upcoming superpowers. Its member countries meet annually at summits to coordinate multilateral policies and consequently, they have developed into a more united economic and geopolitical bloc since their inception.

Source: BSIC

The current economic situation of emerging markets

Over the last fifteen years, economic growth in emerging markets has been considerably faster than growth in developed markets, with an annual growth of 4.2% almost four times bigger than the 1.1% growth recorded in the developed world. Historically, economic growth in these nations has been driven by some combination of a growing middle-class population, increasing investment from both foreign and local sources and technological advancements ameliorating total factor productivity. However, the economic growth premium of emerging markets, that is the difference in economic growth between emerging and developed markets, has moderated more recently, and in fact, fell below the long-term average during the COVID-19 pandemic and bottomed in the first quarter of 2022. However, economists predict that this gap will once again widen in favour of emerging markets primarily due to a weak growth outlook for developed nations but also due to leading indicators, such as manufacturing purchasing managers’ indices, pointing towards a strong economic recovery from emerging markets. Growth in the United States is expected to decelerate, and energy rationing is projected to prolong the economic downturn in European Union whilst the United Kingdom continues to tussle with the aftermath of Brexit and a longer-than-expected contraction. Developed nations also suffer from structural issues pertaining to their slow population growth and ageing demographic. These issues have contributed to anaemic productivity growth in nations such as the United Kingdom where productivity has grown at an annual rate of around 0.5% since 2008, compared to the rate of 2.3% it averaged during the 30 years prior. Some economists even argue that developed nations can reach a point of operating at full economic capacity, where there is no space for them to grow. The Netherlands is one such country that supposedly suffers from this illness, showing symptoms of labour and land shortages. The following decades present emerging markets with a unique opportunity to capitalise on lacklustre growth in many developed.

Over the last two years, economies across the world have seen spiked levels of inflation due to a combination of loose monetary policy, supply bottlenecks following the pandemic, a shock to commodity markets from the Russia-Ukraine conflict and a bounce back in demand and consumption following lockdowns. Many emerging markets, such as Brazil and Peru, tightened both fiscal and monetary policy much faster than the United States, resulting in many Southern American economies appearing to be past the peak of inflation. However, many economies in Central and Eastern Europe such as Hungary continue to see rising inflation predominantly due to the ongoing energy crisis. Inflation is expected to recede later this year due to lower food and energy prices allowing central banks to bring interest rates back down in emerging markets. The recent decline in freight rates and ports delay is a ray of hope for emerging economies this year.

Perhaps one of the biggest threats facing emerging economies is protectionism in the West accompanied by a recent shift towards a deglobalised world. Many political campaigns have won elections by promising to legislate protectionist policies to support local industries and manufacturing jobs. Perhaps the most notable was Donald Trump’s campaign to “Make America Great Again” before he started the trade war with China. It started with America imposing tariffs on solar panel and washing machine imports in 2018 and the most recent development has been America and the European Union blocking the sales of any technology aiding China to develop and manufacture advanced semiconductor chips. Although there have been many attempts to negotiate a trade deal, no such agreement has materialised yet. Due to the trade war, China’s industrial output growth fell to 5% in May 2019, its lowest rate in 17 years, accompanied by a weakening trade balance. In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, many global supply chains broke down when demand bounced back following the lifting of lockdowns across the world. This has led to many companies simplifying their supply chain by bringing production closer to home to make them more resistant to exogenous shocks. At a large scale, this has led to a phenomenon some economists have called “deglobalisation”, where multinationals offshore less production in the developing world. This is another headwind affecting the development prospects of emerging markets over the next few years. Despite the rise of protectionism in the West, there is still a strong dependence on emerging markets that are rich in natural resources. Chile, for example, posted a trade surplus of almost $2bn in February following a deficit of $139m last year. This is predominantly due to Chile being the biggest producer of copper, accounting for 29% of global production, and lithium, accounting for 22% of global production. These resources have proved to be crucial for the electric vehicles industry and its recent growth has benefitted Chile’s trade balance despite protectionism and deglobalisation. It is important to think about the curse of natural resources, where many economists argue that countries which are well-endowed with natural resources often end up with poor economic growth, high levels of corruption and generally worse development outcomes. An example of this is the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The direction in the US dollar moves remains a pivotal influence on the economies and equities of emerging markets. The trade-weighted US dollar Index has typically had a strong negative correlation with real output in emerging economies. The persistent inflation accompanied with interest rate hikes has appreciated the US dollar against other currencies and has been a source of major pain for emerging markets. A strong dollar increases the value of dollar-denominated debt held by governments, corporations and banks in emerging markets as well as raising the cost of servicing this debt. This can ultimately lead to debt crises like we saw when Sri Lanka defaulted on its sovereign debt in April 2022.

All emerging economies are evidently not the same however and have economic growth for unique reasons. India, for example, was the fastest-growing economy last year with an average of 5.5% annual GDP growth over the last decade and is predicted to be the third-largest economy by 2027. The country’s demographic a rapidly growing and the young population has played a significant hand in this. It has provided a large pool of labour and consumers and has consequently been an attractive destination for firms who look to offshore their operations. This has been strongly accommodated by the ambitious program called “Make in India” which is looking to improve the nation’s manufacturing capabilities and generate employment. With a very skilled information technology workforce, the IT and service sectors have become significant contributors to the country’s output. The manufacturing industry has also been a significant contributor to India’s stellar growth over the last few decades. The industry currently accounts for 15.6% of GDP and is projected to grow to 21% of GDP by 2031 and double India’s export market share.

The re-opening of the Chinese economy is another cause for optimism for emerging markets. Not too long ago, the market consensus was that the country’s zero-COVID policy would stay in place for the foreseeable future. Prior to the announcement, the market had priced in a growth rate of 3.5-4% in the Chinese economy, but since then it has been revised up to around 5%. Higher economic growth in China should in theory manifest itself most evidently in rising commodity prices benefitting many neighbouring economies. The Chinese government also announced heavy fiscal stimulus in August to revive the economy after the first half of 2022. They plan to spend over ¥1tn ($146bn), with a particular focus on infrastructure, property, and private businesses. The intervention comes after a series of ineffective expansionary monetary policy measures and aims to sure up the construction and property industry following their recent real estate crisis. The trade war between the United States and China is another tailwind affecting the nation. As estimated, the trade war has had the largest impact on imports from China of products hit with tariffs and their respective industries. This is particularly prevalent in the semiconductor industry where Washington is rapidly ramping up efforts to cripple China’s semiconductor manufacturing industry through strict controls on exports of critical tools and software.

The decade of emerging markets

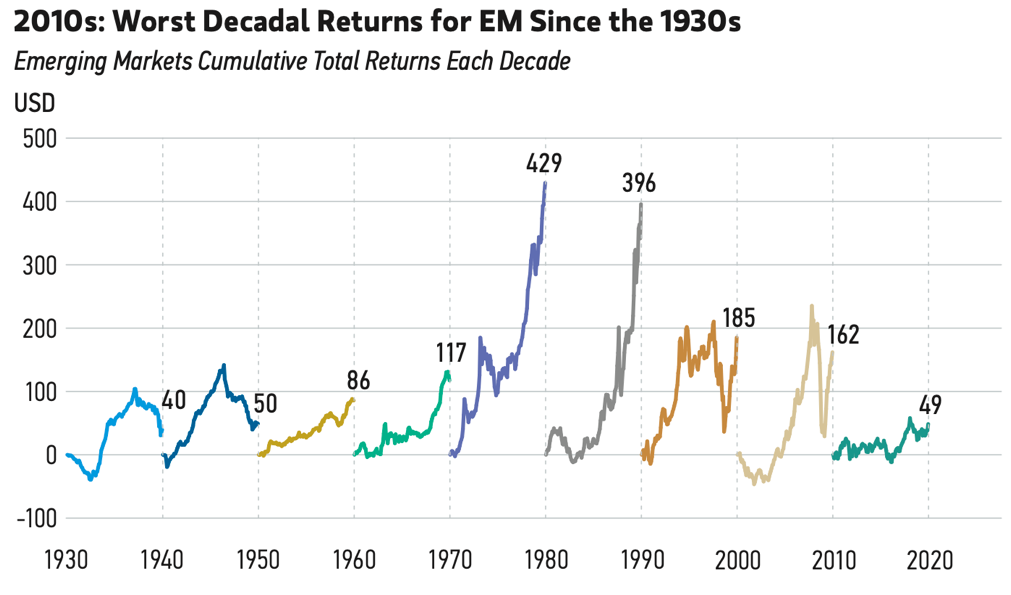

In 2022, 90% of the top-performing markets have been emerging countries, with Brazil, Mexico, India, Indonesia, and the Gulf Cooperation Council represented by the MSCI Emerging Market index outperforming the S&P 500. According to Morningstar’s global projections for the next year, the countries with the highest expected equity annual returns will be Brazil (12.9%), China (11.1%) and South Korea (10.4%), with the best-performing developed market (Germany) at 9.6%. EM is becoming an increasingly interesting investment target, owing to macroeconomic and structural factors; yet, as seen in the graph below, EM suffered its worst decade in the 2010s with a return of +49%, compared to an average of +203%. This poor performance was the result of the deterioration in the growth differential between emerging and developed economies. The graph below provides a visualization of the equity total returns of emerging markets stocks, highlighting peak returns in the 1970s and 1980s. The 2010s had the lowest returns since the 1930s.

Source: MSIM, Bloomberg, FactSet, Haver.

EMs: Fiscal position

GDP growth rate and fiscal health of the governments contribute to the attractiveness of emerging markets, especially compared to their developed markets counterparts. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts a real GDP growth of 4.3% in 2027 for emerging markets and developing economies, compared to 1.7% for advanced economies, with an EM-DM GDP Growth differential of 2.6%, double its value in 2022. Moreover, although China was the main driver of GDP growth in EM over the past few decades, first as a manufacturing world leader and then with consumer internet retailers, many more countries are expected to emerge in the future, especially as high debt and declining working age population will likely weigh down China’s growth. Due to the increasing demand for green metals and minerals to support decarbonization, resource-rich economies such as Chile with their lithium reserves will benefit, helped by increasing digitalization-led productivity and a young population.

Source: BSIC

Alongside GDP growth, the absence of fiscal excesses in EM in recent years is likely to pose an advantage while developed countries struggle with higher budget deficits. As a matter of fact, EM (excluding China) government debt/GDP has fallen by 1% to 53.8% compared to advanced economies, which face an average government debt of 112% of GDP. Simultaneously, EM borrowing has been shifting to local funding, resulting in less outflow vulnerability and currency pressures. This is the case in Indonesia, where 40% of government securities were held by foreign investors in 2017, compared to only 14% today.

Source: BSIC

EMs: Monetary policy

Over the past two years, inflation rose sharply because of supply bottlenecks, increased consumption after a period of uncertainty, expansionary monetary policies and a commodity price shock that resulted from the Russia-Ukraine war. Inflation is a key macroeconomic driver and in 2022, for the first time in two decades, it was lower in Emerging Markets than in the US, with countries such as Brazil, Indonesia, China, and India being almost unscratched by the inflationary pressure of 2022. Even though EMs were traditionally renowned for fiscal expenditures and money printing, their present fiscal posture is viewed as more prudent than that of several DMs, who used Quantitative Easing to alleviate the Economic shock of the Covid-19 Pandemic. With higher GDP growth and lower government debt compared to developed economies, the biggest EMs contained inflation while central banks in developed economies are quickly raising interest rates to counter its effects. Brazil’s central bank chief resisted using Quantitative Easing to increase market liquidity, while the Fed put it in action as early as March 2020. At the start of 2023, however, it seems that inflation might have reached its peak and has, in fact, started to decline due to fewer global supply chain disruptions, excess inventories, and settling demand. Services inflation seems to have stabilized as well, and this trend is expected to continue this year, even though it is not clear how rapidly. Thus, there is a chance that EM central banks will turn to lowering rather than increasing interest rates.

EMs: Deleveraging

Although EMs private external debt has increased over the past five years to $7.4tn in 2021, the acceleration mostly reflects China’s increase borrowing. The rest of the private sector borrowing in emerging economies has flattened, bringing private debt/GDP ratio to 85.5%, a decrease of 4.5%. The deleveraging was led by domestic corporate and household credit and suggests that corporate balance sheets might be overall healthier across EM. Moreover, it seems that the credit market might be able to support higher growth with domestic liquidity and a healthy banking sector.

EMs: De-globalization

Although there seem to be many favourable conditions for EM to thrive, there are a few global trends that may pose a threat to rapid growth. Among all deglobalization, seems to be the most tangible. Since the late 2010s, the world has witnessed the intensification of protectionism and almost a deviation from the high level of openness and interdependency, through events such as Brexit (2016) and the US-China trade war (2018). These events, combined with the growth of nationalism and populism directly damage international economic relationships, harming the outcome or the strength of many economic cooperation projects. The wave of de-globalization seems to be particularly supported by countries that are highly dependent on other economies, as they see reducing their economic dependence as a requirement for national security and as the most effective way to promote their own economic development. The U.S., where almost 68% of companies outsource some of their services, issued the Made in America Act in 2021, to reinforce the Build America, Buy America Act and ensure that certain materials used for Federal infrastructure aid programs are made in the country. Moreover, senators from the Democratic Party proposed the No Tax Breaks for Outsourcing act, which could ensure that multinational corporations pay the same tax rate on profits earned abroad as they do in the U.S. There are many consequences for EM as developed countries make effort to re-shore, or at least nearshore, relocating their manufacturing where they are less vulnerable to sanctions, wars, or supply chain disruptions. Several developing countries have benefited because of globalization, but if they do not learn how to harness their own resources, they may suffer a significant setback. Yet, de-globalization may provide a chance for nations that are rich in natural resources to expand more autonomously. Indonesia is one example of a country that is attempting to use its natural resources, namely nickel and cobalt, to enter worldwide supply chains for electric vehicles. In 2022, President Joko Widodo visited Elon Musk to persuade Tesla to consider manufacturing in Indonesia. In addition, EVs have been identified as a priority industry, which encourages international investment through multi-year tax breaks and import duty exemptions.

Beyond China

China has driven the emerging markets’ economic growth for decades and currently makes up 30% of the MSCI EM index, but investors and analysts are sceptical of its future for different reasons. The first one is that China seems to be at the centre of de-globalization, with manufacturers becoming more self-reliant or moving away to other countries, where wages are low, and skills are relatively high. According to Jitania Kandhari, Head of macroeconomic research on the Emerging Markets Equity team for Morgan Stanley, “Shifting supply chains away from China is creating a lot of manufacturing revival capacity and FDI in other emerging markets, which acts as a growth multiplier in these economies”. However, this phenomenon is not the only aspect that is leading investors away from China. While most EMs are moving towards slimmer budget deficits and companies are slowly deleveraging, China is going against the tide, with local authorities set to issue new debt for $570bn or ¥4tn in the next year according to the Beijing-backed National Institution for Finance and Development. At last measure, the sum of private and public debt in the economy was $51.9tn, almost three times the size of the country’s GDP. Compared to China, countries such as India, one of the most important investment areas for the Morgan Stanley’s Investment Management Fund, where private debt was less than 52% of GDP in 2022 and public debt was around 55% of GDP. Lastly, China’s political environment and unpredictability pose a threat to investors. After three years of zero Covid-19 strategy, Beijing finally reopened its borders in January 2023, sending a positive message and boosting GDP growth predictions for 2023 to 5%. However, tension with the U.S. and the frequent sanctions to which China is subject, especially in the tech industry, with behemoths such as Semiconductor manufactory International, or Huawei Technologies being banned from accessing US technologies have decreased the attractiveness of investments. In the meantime, several other emerging countries have undertaken economic reforms. India is privatizing inefficient state-owned enterprises, such as HLL Lifecare (sold to Adani Group) and Metro AG (sold to Reliance Industries Ltd.) and Indonesia is performing labour reforms, dropping minimum sectorial wages, and adjusting dismissal costs closer to other ASEAN countries. While many Latin American countries are still under socialist governments, they tend to be more fiscally conscious and maintain an independent central bank. The stability of the government and the consciousness behind economic decisions will benefit the quality of growth in these economies, making potential investments more attractive and taking the markets beyond China’s 30% weight on the MSCI EM index.

Typical EM Capital Flow Behaviour

Historically, emerging markets investment has been treated as a high-risk asset class for private investors, leading to significant outflows during times of de-risking and uncertainty. A recent example of this phenomenon lies in the $65bn Maryland State Retirement and Pension System’s recent decision to reduce the fund’s allocation to emerging markets to 10% from 14% (WSJ), with Chinese exposure seeing a 2% reduction to 5%. Other large US asset managers are following suit, with the Teacher Retirement System of Texas, which controls a $184bn state trust, cutting its target allocation to China by half within its emerging markets portfolio. While these managers delve primarily into public equities investing, we can apply this same de-risking trend to private markets, as China experienced a sizeable decline in US Private Equity and Venture Capital investments.

China-Specific Risk Factors

Taking a closer look at specific factors which influenced this drawdown, we may cite the unpredictable actions of the CCP, which has dealt consecutive blows to the financial sector. The Chinese Authorities are widely believed to have detained Chinese deal making titan Bao Fan, head of the investment bank China Renaissance. While his disappearance led to a devastating ~30% drawdown of the firm’s market capitalization, to ~$515m from over $700m. this negative effect was simply the latest in a string of government-led actions which harmed the firm and the financial sector. For example, the FT reports that Chinese regulation on the tech industry led China Renaissance revenue to fall “by more than 40% from a year earlier, pushing the Firm from a $175m profit for the first half of 2021 to a loss of ~$22m.” Other dealmakers at the firm such as Cong Lin, a central figure in China Renaissance’s partnership with ICBC international, have been quietly removed from their positions following regulatory meetings with government officials. Clearly, private-market dealmakers are experiencing significant government interference – a perception which has been picked up by private market managers in developed economies. From a foreign private investment perspective, the purge of top dealmakers at some of China’s most influential firms casts doubt on a foreign investor’s ability to access reliable advisory and capital markets solutions in-country. Developments such as those at China Renaissance are but the latest pressure on a hostile deal making environment. In late 2022, the United States added 36 Chinese semiconductor manufacturing firms to its trade-restricted “entity list”, demanding that firms prove they do not supply China’s military, disrupting critical trade relationships and forcing firms such as YMTC, China’s largest memory manufacturer, to slow expansion and plan layoffs. In turn, Chinese officials have engaged in a review of battery maker CATL’s partnership with Ford – all to ensure key Chinese battery technology is not openly shared with the American firm. This implied escalation, combined with China’s incessant zero-covid policy, spooked emerging market investors, leading to a significant decline in exit opportunities as Hong Kong IPOs slump – due in part to international investor’s concerns about regulatory crackdowns in the region.

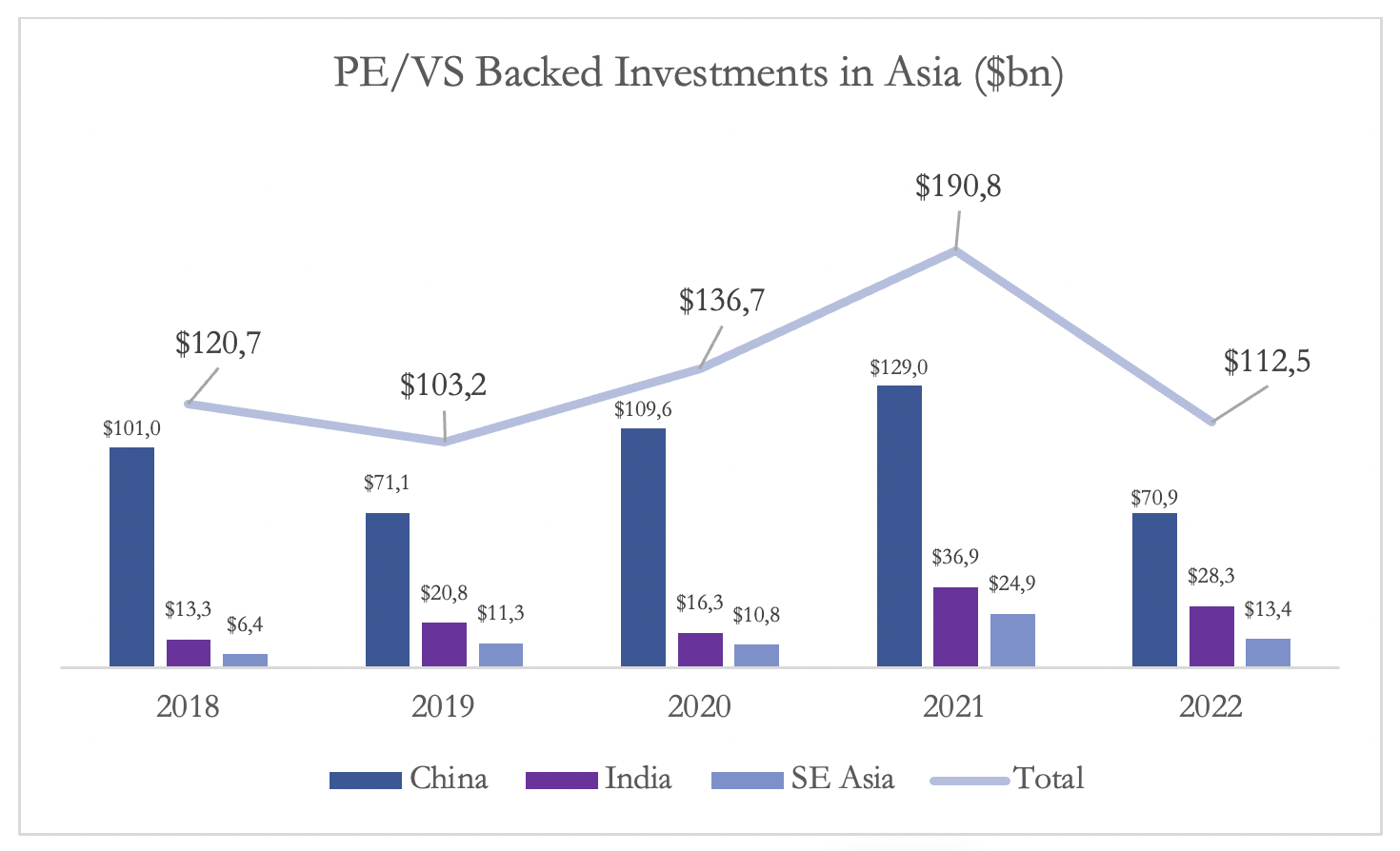

According to S&P Global, “the aggregate value of US investments in China declined roughly 76% year over year to $7.02bn from $28.92bn, and the number of deals dropped about 40% to 208 from 346”. This decline left investors searching for other possible allocations to retain their exposure to an emerging market, leading many to consider India and Southeast Asia as potential avenues of expansion.

Transition to India and Southeast Asia

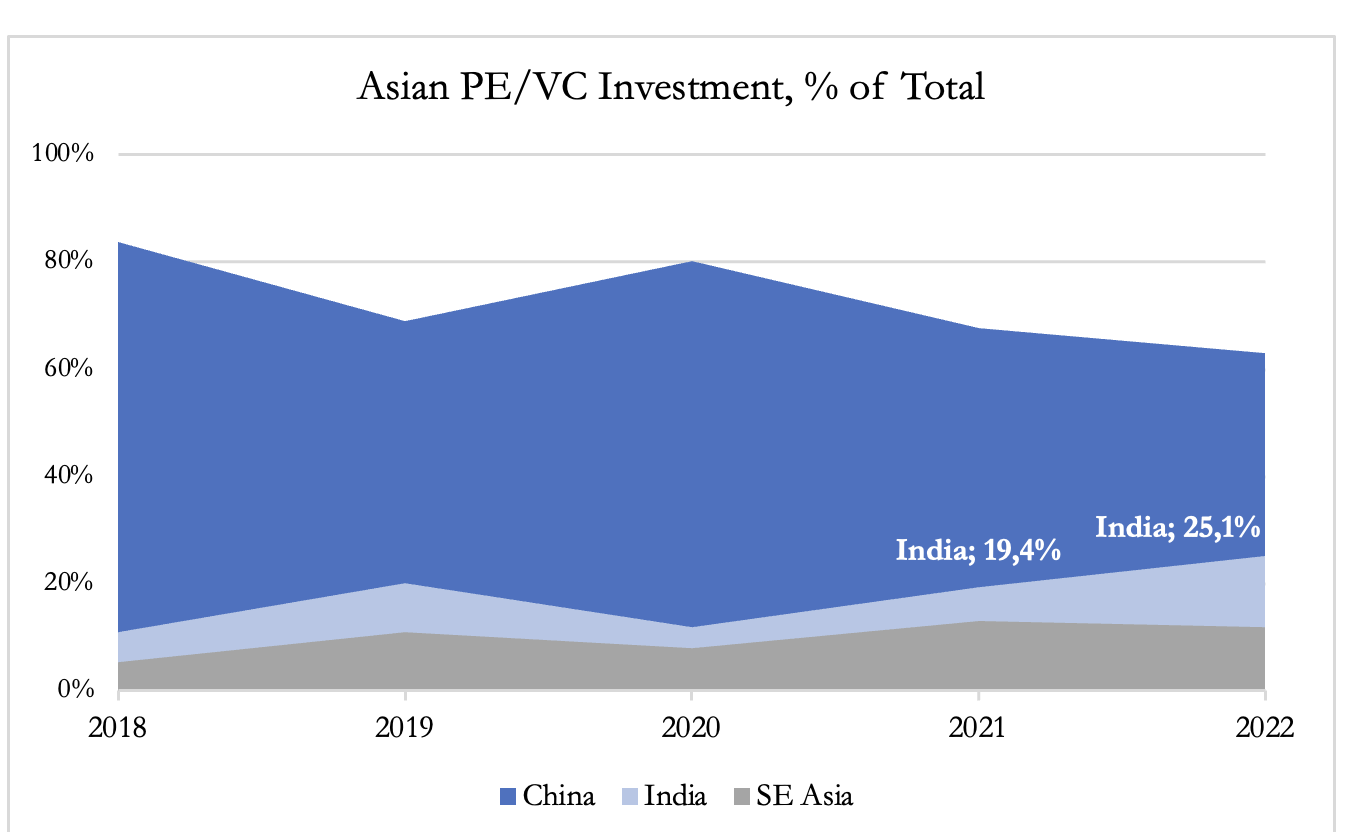

While the Chinese regulatory environment becomes increasingly hostile, India has taken material steps to improve its foreign investment environment. Improved tax dispute systems through the uniform Goods and Services Tax (GST) have eliminated many retrospective changes in tax laws which dissuaded foreign investment. At the same time, increased trade-policy alignment with the West continues to entice investors towards India, as the country finalizes free-trade area deals with the UAE and Australia, while deals with the UK, Canada, and EU are in progress. These efforts are concerted to better allow foreign investors to deploy capital in the region. Although Indian private equity markets experienced a notable decline in capital flows in 2022 of 23.4% YoY, this represents a significantly smaller percentage decline relative to China, highlighting investors’ lower perceived risk in the region. As China’s relative share of all Asian investment declined by 45.1% YoY, India’s percentage share increased to 25.1% in 2022 from 11.9% in 2020. The graph below shows investment in different Asian EM regions as a proportion of all Asian PE/VC investments.

Source: Capital IQ

Adani Group, GQG, and the search for alternatives

We have established emerging markets as a relatively high-risk allocation for developed market investors, positioning them as one of the first asset classes to experience reductions in total allocation during global crises or drawdowns. While reduced investment in China may be attributed to unpredictable government action, evidence from India highlights how although many investors prefer Indiana investment opportunities, this market remains subject to transparency and accounting risks inherent in developing economies. Following Hindenburg’s research’s comprehensive report regarding Indian Tycoon Gautam Adani’s conglomerate, additional scepticism has arisen regarding the validity of Indian controls and accounting principles. However, in contrast to many Chinese investment scenarios, where US-based asset managers uniformly reduce exposure, some domestic asset managers seem comfortable taking a contrarian position in the Adani case. On March 2nd, GQG which is USA-based and Australia-listed, announced a $1.9bn investment in Adani Enterprises and three of its subsidiaries – operating in ports, electricity, and green energy. GQG founder Rajiv Jain was quoted by the Financial Times as stating “What is not being appreciated is that these are assets run by very competent management – the execution capabilities are fantastic. We fact-checked everything and we felt the market was mispricing Adani”. GQG is joined in support of the embattled firm by an anonymous sovereign wealth fund, which was widely reported to have contributed $3bn to a credit line for Adani, offering further support to the Indian firm – a stark contrast to the sustained falls from grace of Chinese firms subject to government action.

Jain’s quotation highlights one of the key factors influencing the continued willingness of domestic firms to maintain Indian exposure – the type of risks present in a given EM country. While investors flow towards India and its improving environment, arbitrary Chinese regulation, and rising tensions screen as higher potential risk factors. When Jain speaks on his firm’s in-house valuation of their Adani investment, the risks GQG seeks to mitigate are large regarding the accounting and cash flow validity of Adani group. This risk, through extensive research and fact-checking, may be effectively mitigated (as displayed by GQG’s continued investment). However, the risks inherent in the Chinese businesses may not be understood through extensive firm research, as they are a direct product of government actions, which by their very nature are highly unpredictable.

An exception to the rule: Private Credit

While PE and VC inflows into all emerging markets declined by 30% and 33% respectively YoY in 2022, private credit investment remained exceptionally strong, with an 89% YoY increase to $10.8bn. The Global Private Capital Association cited strong deal making related to infrastructure and energy in developing markets. To further explore this increase, we consider specific cases which we may extrapolate to explain much of this sustained investment.

The resilience of EM Infrastructure Outlays

After considering the decline in EM private capital investment through a geographic lens, we shift to a view of capital inflows through an industry focus. As stated earlier, an 89% YoY increase in flows to private credit investment in emerging markets was largely driven by infrastructure, energy and renewables, even as private equity inflows tapered. Reuters reports that private credit issuance provides a stable financing option for developing economies, which may lack the local banking capacity and risk tolerance to fund meaningful projects.

An explanation for these increased private credit issuances lies in a heavy focus in renewables and sustainable infrastructure from developed countries, both in the government and private sector. On the private side, firms including Macquarie and Brookfield retain renewables investing as a core tenant of their business model – some with an explicit focus on emerging markets. A notable transaction in 2022 occurred when US Private Equity Giant KKR took a $400m stake in the equity of Indian decarbonization platform Serentica Renewables. Although most private credit deals retain a lower value than the KKR equity transaction, this high-profile investment conveys the willingness of private EM investors to take on infrastructure and renewables risk, notwithstanding unfavourable market conditions in other verticals of private markets investing. On the public side, we see several government entities supporting capital inflows. A specific case took place when the IFC (part of the World Bank Group) led a $4.4bn investment in private sector development in Brazil, including a $150m loan to SABESP, one of the largest sanitation firms in the world. The loan was issued through the Utilities for Climate (U4C) initiative and represents one of many altruistic movements that are actively engaged in supporting sustainable recoveries for developing countries. These actions highlight the willingness of asset managers to allocate to emerging markets’ infrastructure despite the reduction in global PE activity.

The future of Emerging Markets

We have seen that 2023 has started with a spike in emerging market equities, prompting many economists and experts to call the next ten years the emerging market decade. Even though these thriving economies are fundamentally different, with nations like Poland benefiting from its EU membership and others like India growing due to their vast size and young population, they are all characterized by high growth opportunities and significant development in the coming years. The fact that these nations have enormous reserves of key resources for the green transition, such as cobalt, nickel, and lithium represents a major strategic advantage in a world that is becoming less unipolar, with the West and China competing for resources and hence building strong ties with these nations. In return for resources, China is spending heavily on infrastructure projects, while the US is encouraging the start-up environment and is offering financial assistance; therefore, this competition leads to improved agreements for emerging nations. Even though we are currently experiencing a strong-dollar scenario, which tends to affect Emerging Markets since their foreign debt is usually denominated in dollars, these countries have a better fiscal situation than many developed countries (looking at Total Debt/GDP) due to a more prudent monetary policy in the Pandemic and proximity to natural resources, resulting in lower inflation prospects.

Source: Capital IQ

With high-interest rates around the world and fears of a new economic crisis, we would expect to see a continued decline of Private Investments into emerging markets in 2023, as these areas pose a higher risk, while recent events such as the Adani controversy are not helping the perception of international investors. Although, in the long term, digitalization, infrastructure, and sustainability initiatives, along with more efficient financial markets and transparent regulation, will attract massive amounts of capital from abroad.

0 Comments