Introduction

Throughout history, gold has played a central role in the economies of the world. With its uses ranging from a store of value and currency to an indicator of wealth, it still stirs up heated debate. With the global gold mining industry, worth just shy of $205bn in 2022, undergoing consolidation, it beckons an in-depth look. Only recently, Newmont, biggest gold miner globally, announced its intentions to take over Newcrest, its once-owned Australian subsidiary. Provided an agreement will be reached, the deal is bound to mark of the costliest transactions this year.

With this piece, we initiate a new series of articles that will provide you with even more extensive and complex analyses covering a range of industries and trends dominating them. It’s our pleasure to present you: Our Analysts’ Take.

About Newmont

Newmont is the world’s largest gold company. Founded in 1921, its assets and ~31,600 employees span 4 continents, with its headquarters being set in Denver, Colorado. It is actively involved in the production and extraction of copper, zinc, silver, and lead and these activities in tandem with its gold extraction bring its total land position to over 62,800 square kilometres.

The bid for Newcrest comes 3 years after a $10bn takeover of Canadas Goldcorp, which is what saw Newmont cement its status as the world’s preeminent gold miner. Since the bid in 2019, EBITDA has increased by 62% to c. $6bn as of 2021, with c. $1.7bn in Capex, and overall free cash flows of c. $2.6bn in the same year. With over $24bn in total assets, the Newcrest bid is Newmont looking to bring consolidation to an already consolidating, and its (now rejected) $17bn offer would already serve to make it the largest gold mining takeover of all time. The result of the transaction would be 4 out of the 5 largest Australian gold mines being controlled by one company, with anti-trust laws requiring the Australian government to review the transaction before anything could be finalized.

About Newcrest

Newcrest is a Melbourne-based Australian extraction corporation engaged in the mining and production of gold and gold-copper concentrate. Founded in its current state in 1966 as Newmont’s Australian-arm, and then later spun out to merge with BHP Gold Ltd, it controls most of all Australian gold mining operations.

Newcrest’s assets are primarily composed of low-cost and long-life mines primarily in Oceania, and more recently in North America. It is the largest listed gold miner in Australia with approx. $6bn in total assets at the end of its most recent fiscal year (June 2022). Despite this and a 16% spike in revenue during the pandemic in 2020, it saw a slight decrease in EBITDA down to approx. $1.9bn as of the end of its last fiscal year, down from an admittedly inflated $2.2bn in the period before last. It was caused by a spike in global gold prices due to rising input costs in tandem with steadily declining gold output (25% in 2022). Newcrest will see over a quarter of its revenues come from copper in the next decade as the world decarbonizes and requires more of the metal, and has already seen copper output rise 32% as of the end of the 2022 FY.

Deal rationale & implications

With an annual production of 8 to 8.5 million ounces of gold, the merged firms’ market value would be around $57bn after the all-shares transaction, putting them roughly $30bn and 4 million ounces ahead of their closest rival, Barrick Gold Corp. By acquiring Newcrest’s two mines in the area, Newmont would additionally be able to improve their presence in British Columbia, a key growth area. In addition, from the perspective of strategic expansion, Newcrest’s copper contingent is a business sector to which Newmont currently only has little exposure, but a desire to expand. To increase copper production to account for “15–20% of its overall output by the end of the decade,” Newmont’s CEO Tom Palmer stated that he was willing to explore large-scale copper acquisitions, of which Newcrest is a prime example of. The street believes that the offer did not appropriately value the long lifetimes of Newcrest’s assets, such as its scaling copper production, and that this was a major factor in why the bid was allegedly rejected.

Despite this, analysts are generally not convinced of the overarching motive for the transaction. Citigroup and other have described the potential prevailing operating synergies as “de-minimus”. These comments are backed up by other major mining industry players such as Barrick Gold Corp and Agnico, and were arguably best explained by Mark Bristow, the CEO of Barrick’s stated reason for why his firm would not placing a bid on Newcrest. “Scaling to scale” is not a long-term and sustainable strategy.

Most other mining companies now take a “surgical” approach to asset selection, looking for agreements and areas where the greatest possible synergies can be realized. However, this behaviour is relatively new. The gold mining industry is estimated to have incurred over $85bn in impairment charges between 2010 and 2017, which is far more than what analysts believe is typical for this industry. Globally significant firms in the sector were merging to reach the size of significant players in the energy sectors, or even other industries producing commodities like iron ore and steel, for example. Beyond only making the remarks described above, Bristow oversaw a transformation in the sector that have been gradually giving consolidations a purpose. The finest example of this is Barrick’s $6bn 2018 merger with a Malian company at a 0% premium. The idea was that by combining the firm’s assets under a single management team, they would naturally appreciate through all but perfect synergies, which is exactly what has happened four years later, with Barrick’s having met all its guidance and even aiming to prolong the lives of its mines in Mali.

Beyond the significant impairment over the past decade, leading miners and analysts predict that industry consolidation will continue to rise, partly in response to investor demand for larger, more liquid gold mining enterprises but also to create stronger and more successful organizations. Through rising production costs and deteriorating metal grades, investors will still need to strive to maintain their margins, and M&A will most likely continue to be a driver. A period of lower realized gold and copper prices decreasing profits while increased activities and inflation continue to drive up costs may be offering Newmont a dip in the recently inflated prices, but analysts believe the largest gold mining corporation paying a (now expected greater than) 21% premium to add 8 mines doesn’t add much else to Newmont’s business other than further material complexity.

Where it all starts – mining the commodity

The gold mining business has changed dramatically over the past centuries, due to technological advances and increasing regulation of work conditions. Mining companies, through a capital-intensive process that requires a huge amount of PP&E and Capex over time, have the final goal of finding, processing, and refining gold. The final product is then an ore bar, typified by very specific standards, with different weights and purity levels.

The first step of the activity is the search for land where to mine. This process, known as the “research process,” includes the work of geologists and industry professionals who, through complex predictive models based on soil characteristics, can highlight certain critical areas where mineral deposits might be found. Once the areas have been identified, it is necessary to apply for the necessary permits to begin actual exploration activities. There are, in this regard, several legal complexities. In fact, once under common law, the minerals under the land belonged to the owner of that land. Today, in most countries, the area under the ground is owned by the state, which, through licenses, can grant mining companies the ability to use them. Therefore, mining companies usually don’t own the land where they mine.

However, not all identified areas by the research are “fruitful”. Estimates suggest that only the 10% of gold deposits contain sufficient gold to make mining economically convenient. That said, lands also contain other precious minerals, such as silver and copper, leading to “revenues synergies”. Mining requires many upfront costs, the main items of which are the cost of PP&E and exploration: net PP&E is, on average, between 50% and 60% of total assets of a mining company. Mining costs also depend on the type of mine: surface mines require, on average, lower costs, while underground mines require higher costs.

Yet, once obtained the license to dig, not all costs should be considered when assessing the economic viability of a quarry, as many of them are referred to as “sunk costs”. Examples of this type of costs are licenses, machinery, cost of exploration, and personnel employed already present in the firm, even if allocated to the project.

True cost-effectiveness valuation should be focused on three main components:

- The estimated amount of gold that can be obtained from a quarry, with the following expected revenues obtainable and including additional revenues from other minerals found.

- The expected cost associated with opening and maintaining the quarry, the subsequent cost of refining gold and reclamation costs.

- Time value of money and risk factors, respectively accounted for through the discount rate, and scenario analysis. The scenario analysis should be based on (1) forward price of the gold scenario and (2) amount of gold found.

However, while the amount of gold can be estimated in a quite accurate way, the price of gold is hard to predict, especially considering the long-lasting production cycle of gold.

Once convenience is established, excavation work begins and lasts for a time between 1 and 10 years. The excavated earth is then chemically processed to obtain gold, which, however, is still unrefined. Gold refining is outsourced to specialized companies, which then ship the gold bars back to the mining company.

Price determination and why gold remains so valuable

The value of gold lies behind its symbolic value, which has been protracted since ancient times. Such prestige leads gold to be a timeless material that remains stable even in adverse economic cycle phases. The jewellery industry (and the luxury industry in general) is the largest demander of gold in the world, accounting for about half of the total demand. Gold is also used in the technological, medical, electronics, automotive, defence, and aerospace industries.

Gold mining companies have 5 main direct types of customers: industrial manufacturers, jewellery manufacturers, central banks, investors, and retailers.

However, there may be not enough demand from direct customers at the time when the gold is ready. Given the time lag between the production and the sale, gold is stored in bullion banks. Bullion banks have a “clearing role”, operating as a market maker: when the gold mining companies want to sell, the bullion banks buy. When a customer wants to buy, the bullion bank sells the previously bought gold. The price is determined by different gold markets, such as the OTC (in New York), the gold futures market, and the London Fix.

While the largest amount of gold is vaulted (held for central banks and investors, like ETF investors), less than half of the gold produced goes to the jewellery industry. China is the largest market for gold jewellery, with about 673 tons demanded in 2021, followed by India (611 tons) and the Middle East (241 tons).

The main role of bullion banks is to provide liquidity, hedging, and trading services to the gold industry.

Let’s make an example: a Chinese jewellery maker needs a certain amount of gold, with a specific level of purity. It asks its partnered bullion bank for that gold and the bank ships it to the customer. The price of gold bullion is influenced by demand from companies that use gold to make jewellery and other products. The price is also impacted by perceptions of the overall economy. For example, gold becomes more popular as an investment during times of economic instability.

“Rainy day” asset

Gold is “special” due to its status as both a commodity and a currency, as in a storage of wealth. It is known as a “rainy day” asset, thanks to historically being a hedge for times of macroeconomics uncertainty. Between 1973 and 1979 it provided investors with a 35% return during times of high inflation. Nevertheless, its returns in the last 10 years have been negative, at -0.05%, compared to the S&P which provided investors with an average return of above 14% between 2011 and 2021. The consensus of analysts is that gold does indeed hold its value over time and can be a good investment, but only if held for longer periods of time (12-18 months) and bought in anticipation of a macroeconomic crisis. Otherwise, equities fare much better.

Economics of the industry

By adopting a supply-side approach, one can better understand the problems with the long cycle of gold production. Suppose there is a period when the price of gold is at a given level and there is a certain number of mining companies that are looking for gold. Such companies, currently, are having difficulty finding land with enough gold to be convenient to dig. As a result, prospecting, digging, and production times are increasing. This leads, in the short term, to a gold shortage. Assuming a constant demand for gold, the price of gold would increase. A higher gold price makes mining more profitable: more companies will start digging more land, as the breakeven point has been reduced due to increased unit revenues from gold. Greater number of companies leads to a subsequent growth in supply of gold, driving down its price. At this point, companies will exit the market, and/or fewer digging sites will be started. The cycle at that point begins again and lasts for a time between 10-20 years.

The length of the gold production cycle is a critical risk factor that should be assessed when evaluating an investment and/or a new venture.

Global trends in the industry, competition, and sources of competitive advantage

According to Azoth Analytics, the global gold mining market was valued at $204.27bn in the year 2022 and it’s expected to grow at a CAGR of 5.3% over the next 5 years, reaching a total value of $264.31bn in 2027. The global gold mining market is consolidated, and the top players account for a significant share of the market. Most notable manufacturers of gold mining include Newmont Corp., Barrick Gold Corp., AngloGold Ashanti, Polyus, Kinross, Gold Fields, Newcrest, Agnico Eagle, Polymetal, and Kirkland Lake. In 2022 the 10 main players accounted for around 25% of the total market share, but this number is expected to increase due to a consolidating market.

Since gold is a commodity, the market is not differentiated. However, there are high barriers to entry given the significant amount of fixed costs required to acquire PP&E needed to perform the digging activity. The regulation assumes a key role in the industry and the country where the mining company works is therefore essential. Obtaining permits for the construction of excavation sites depends on the jurisdiction: the faster the bureaucracy, the faster the speed in obtaining permits, and the lower the cost of waiting and uncertainty. The skill of geologists, engineers, and chemists is a critical element of competitive advantage: the success of a mining company depends heavily on its ability to identify the most profitable places to dig. For the same mining cost, the greater the amount of gold mined, the greater the profit. So, heavy investments in advanced technological software, machinery and skilled personnel are critical to the company’s success.

M&A activity in the industry

Due to gold’s high regard as an asset, the gold mining industry has been closely followed by analysts. Newmont’s recent bid for Newcrest is an important indicator of a trend of industry consolidation. Indeed, just last year, two important deals kicked off this trend. In February 2022, the third largest player in the gold mining industry, Canada-based Agnico Eagle Mines agreed to a merger of equals with Kirkland Lake Gold, with shareholders of the latter company receiving 0.7935 per share of the new firm, which kept the Agnico name and brand. Just a few months later, in November 2022, the same Agnico, together with Pan American Silver agreed to the acquisition of Yamana Gold for $4.8bn, after a previous agreement worth $6.7bn with South Africa’s Gold Field fell through because of a slump in Yamana shares that brought the deal’s value to $4bn and led Gold Field shareholders to unanimously vote against the deal. The deal saw the acquired company get broken up, with Pan American buying all outstanding common shares and selling to Agnico mostly assets in Canada, such as the Canadian Malartic Mine.

With 2023 marking potentially the third blockbuster deal in the past year in the gold mining industry, there is a clear desire for consolidation by the large players in this industry. This is mostly driven by commitment to net zero that most companies want to achieve by 2050. Cutting emissions means investing in electric trucks and renewable energy to operate the mines, which requires scale and ownership of long-life mines. This can only be done by multi-billion-dollar companies, which are few and thus striving to acquire the smaller players, which in turn, want to be acquired.

Valuation – DCF

Mining companies are usually valued using a DCF for each project the company undertakes. This method is preferred for medium to large companies which usually conduct feasibility studies on projects that are essential to estimating future cashflows. Key components of feasibility studies are the volume and grade of the underlying resource, in this case – gold. Gold grade measures the quality of the ore, that is, the raw material extracted from the mine. The higher these two measures, the more expensive the asset is.

The highest-grade gold mine in the world is Agnico Eagle’s Fosterville Mine in Australia. The WACC currently used in the gold industry is 7-8%, but it is important to note that due to a lot of mines being in countries with deficits of democracy, the country’s risk is one of the main factors that results in fluctuations of the WACC. For instance, Canada’s country risk premium is 0%, while Nigeria’s is just over 11%, according to Damodaran. A higher country risk premium results in an increase in the cost of equity.

Valuation – Multiples

Multiples are used for mines that do not have a feasibility study. The multiples used are Price to Net Asset Value (P/NAV), calculated as the ratio between the market capitalisation and the NPV of mining assets plus minority interest and cash, with NPV of overhead and Net debt being subtracted. The Price to Cash Flow ratio is also widely used, as well as EV/Resource, which is the least indicative multiple and usually used for projects in early stages of development. It is calculated by dividing Enterprise Value by the total ounces of gold ore and does not consider capital cost and operating costs. Lastly, Total Acquisition Cost (TAC) is another frequently used multiple, calculated by dividing the sum of the cost of acquiring the mine, building costs and the cost to operate by total ounces of gold ore.

Main financial ratios

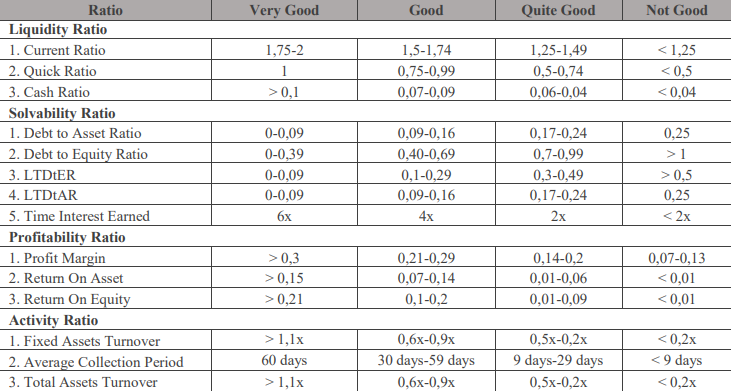

When it comes to the mining industry, especially the precious metals and gemstone mining subset of this industry, there are a series of financial ratios to look out for. The most relevant include profitability ratios such as the Operating Profit margin and the ROE, liquidity ratios such as the Quick ratio and solvency ratios such as Debt-to-Equity. The following table shows how different values of the ratios are traditionally considered for a gold mining company.

Source: Putri, Keisya Oviriska, 2011. Financial Ratio Analysis to Assess the Performance of Mining Sector Company in United Tractor Semen Gresik Ltd., Period 2011-2015. Brawijaya University

Investors and analysts keep a close look on these ratios due to the intricacies of mining operations and the particularities of the industry. One such particularity is the high proportion of Fixed Assets to Total Assets, making the Quick Ratio a key metric to measure liquidity. The Operating Margin is also relevant, as mining requires frequent adjustments to production levels which can significantly impact operating costs, if operations are not well managed. Nevertheless, profitability ratios that are generally relevant for companies are no exception for the gold mining industry, such as the ROE.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the gold industry is a strongly consolidated sector that will probably see further consolidation in the coming years. Gold mining companies have three main risks to consider: (1) fluctuations in the price of gold, (2) the regulation of the various countries where mining takes place, with reference to obtaining the necessary licenses, and (3) the accuracy of exploration studies to identify gold deposits effectively and efficiently, granted by continuous investments and advances in technology.

The most widely used method of evaluation is the DCF, with WACC averaging around 7-8%. This parameter is influenced by the size of the mining company and the country where the activities predominantly take place. The Price/NAV, EV/Resources and Price to Cash-flow ratio are the most common multiples, while ROE is a suitable indicator for profitability.

0 Comments