Introduction

At its core, the private credit industry refers to direct loans not negotiated in the traditional public environment and brings unique characteristics that improve this asset class’s resilience. In times of elevated interest rates, traditional banks have become increasingly conservative in lending policies due to concerns about companies’ ability to repay debt, leading to fewer loans being given out. This movement creates a market gap, where businesses’ demand for financing remains constant and credit is scarce. With traditional institutions pulling back, private lenders fill the void, offering higher returns for investors, flexible contracts and volatility hedges.

In a scenario where fixed-income investors struggle to earn satisfactory returns on long-term investments, the allure of private credit lies in its higher return potential. The floating rate loans, often found in private credit arrangements, increase with interest rate hikes making this asset class attractive. Lenders demand this enhanced yield to compensate for the increased risk and flexibility to tailor contract terms accordingly.

Furthermore, the private credit fundraising environment has surged as institutional investors seek less volatile and correlated assets. The combination of being a short-term investment, with thorough due diligence and the fact that private assets aren’t exposed to mark-to-market fluctuations, heightens their appeal to investors.

“Malicious” Lending Practices

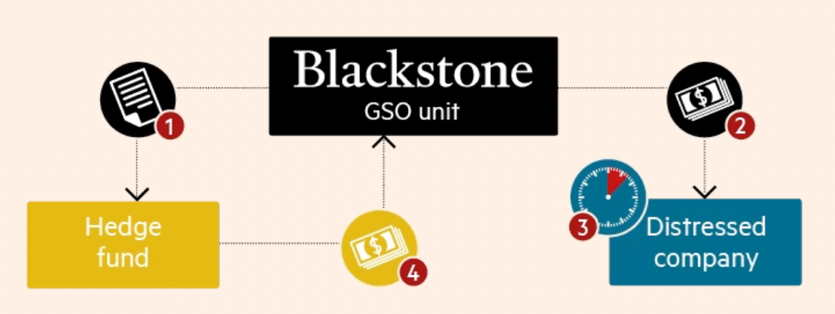

Everyone loves the saying there’s no such thing as a free lunch, but when you’re Blackstone’s [NYSE: BX] GSO Capital Partners it’s pretty close. Successful people in the financial services industry have always been able to carefully look at regulation and skirt the rules to gain an edge in an increasingly competitive market. No one was better at leveraging Blackstone’s size than its GSO unit led fearlessly by Akshay Shah. Utilizing an innovative trade that came to be known as the “manufactured default”, Blackstone GSO would:

- Buy a credit default swap (CDS) contract on a struggling company from another hedge fund

- They would then approach the company and offer it very attractive financing on the condition that it must default in a way that would trigger a payout on the CDS contract

- The company then carried out this proposal, for example by paying interest on a bond a few days late, causing little concern to bondholders but “triggering” the CDS contracts

- The hedge fund would then have to pay a lump sum to GSO given that the company had defaulted

Source: Financial Times

Clearly, it didn’t take long before US and UK regulators caught wind of the situation and condemned the financial engineering in the derivatives business. They agreed to work together to regulate this practice that had companies without financial distress defaulting on their debt, which they deemed as gaming the credit default swap market. Several government agencies including the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and the Financial Conduct Authority of the United Kingdom all issued warnings regarding Blackstone’s innovative strategy, particularly in the case of their agreement with Hovnanian [NYSE: HOV]. Hovnanian – a home builder that focuses on American real estate – saw the opportunity to receive an extremely profitable financing deal from Blackstone GSO in exchange for a manufactured default. Hovnanian ignored a bond payment that it owed to one of its subsidiaries and the lack of payment triggered the swaps on their debt. Blackstone profited largely from this as the insurance pay-outs outweighed the smaller win they made on the private credit side of the transaction.

This transaction raised several eyebrows, as investors knew that Hovnanian had the liquidity to pay its debts – deeming the trade as underhanded and fearing that it would spark a new trend in the market of false defaults. Government agencies declared that these defaults “may adversely affect the integrity, confidence and reputation of the credit derivatives markets, as well as markets more generally.” In this case, Goldman Sachs [NYSE: GS] and Solus Alternative Asset Management drew the short end of the stick as they were on the hook for the insurance payments.

The government agency most infuriated by this feat of financial engineering was the CFTC who launched an investigation that ultimately led to an agreement between Blackstone, Goldman and Solus. Their stance was that credit default swaps existed as a source of lender protection and that this practice would scare off market participants.

Throughout the 2010s, Blackstone grew and kept leveraging the reach of its private equity group and name brand to keep accumulating large AUM across all strategies and profiting thanks to all kinds of financial engineering. In cases like their agreement with Hovnanian and other companies like Codere [NASDAQ: CODR] they were able to leverage their ability and holes in regulation to profit. To read more about the Blackstone way to trade CDS we have written an article in 2018 that goes into the financials in depth here.

In 2020, Blackstone changed the name of their credit unit from GSO Capital Partners to Blackstone Credit in an effort to rebrand what investors came to know about their credit arm.

Shift towards nicer lending

The higher for longer interest rates that the market can expect to continue seeing will undoubtedly lead to an expanded market share for private credit. As it becomes a crucial part of the global alternatives market exceeding $1.3tn in AUM, direct lending has established itself as the flagship subsector representing 44% of all private credit assets. Although its performance is less exciting, a study by BlackRock [NYSE: BLK] tracking the performance of the direct lending asset class by using the Cliffwater Direct Lending Index (CDLI) as a proxy demonstrated that the “CDLI has outperformed the U.S. HY bond and US leveraged loan indices for 12 of the last 17 years, as well as through the first three quarters of 2022 (most recent data available).”

Another advantage of direct lending is its limited downside which allows it to perform strongly compared to public markets especially in times of economic turmoil such as the Covid-19 Pandemic. All these factors have culminated in Private Equity giants inflating and re-investing in their credit arms with a strong focus on vanilla direct lending – a stark comparison to the creative feats of financial engineering led my Mr. Shah just a couple years ago.

Unitranches have constantly increased starting in 2021 with three loans worth more than $2bn in a short time span, including a record $2.6bn loan for Thoma Bravo’s buyout of Stamps.com. In April of 2023, Blackstone sought to raise $10bn for an exclusive direct lending vintage and has backed take privates this year using its credit arm. Earlier this year they issued a £1.25bn direct loan to support EQT’s recent purchase of Dechra Pharmaceuticals in cooperation with Goldman Sachs. Additionally, a group of lenders led by private-equity firm Apollo Global Management [NYSE: APO] provided as much as $2bn to Wolfspeed to support the semiconductor maker’s expansion in the US, according to Bloomberg. This whole uprise culminated earlier this year in February with the record setting private credit deal orchestrated to fund the buyout of healthcare company Cotiviti with a $5.5bn loan. Although this particular transaction ran into problems in April, it is undoubtedly telling of where the private credit market is going in the future.

Don’t poke the bear – Blackstone & Bain Capital

During 2023, banks including Bank of America, Barclays and Morgan Stanley that got stuck holding billions of dollars of leveraged loans in 2022 are sitting on the sidelines as leveraged buyouts (LBO’s) revive. Moreover, big banks are especially avoiding deals that could draw low ratings from the credit rating agencies. This has led to an increased number of loans being directly arranged. Now, buyers have been pushed towards costlier debt provided by private credit funds such as Blackstone, Sixth Street, Blue Owl, Apollo, KKR, Carlyle and others. Stephen Schwarzman, Blackstone’s founder and chairman, said in September 2023 that double-digit returns could be made by lending to companies with almost no prospect of loss. However, this is not necessarily always the case, as companies may collapse and funds may not be able to recover all their money, a situation Blackstone is facing currently.

In March 2017, Bain Capital [NYSE: BCSF] Private Equity one of the world’s largest private equity funds, announced the definitive agreement to acquire Fintyre, Italy’s leading distributor of replacement tyres. This acquisition was part of Bain Capital Europe Fund IV, which raised over €3.5bn. In 2016, Fintyre generated sales of more than €400m to more than 15,000 customers, mostly across northern and central Italy. The company had a 20% market share of the domestic market and was further developing their retail network, having acquired over 40 sites in Italy as well as developing partnerships with e-commerce retailers such as Amazon and eBay. Bain Capital partnered with the company’s management team to pursue a growth strategy to further consolidate their leadership position. Moreover, Blackstone provided over €200m of debt funding for the deal.

Initially, everything went well with the investment. In April 2018, Fintyre acquired La Genovese gomme (LGg), a family-owned company involved in the wholesale, retail, retreatment of tires and assistance services based in Sardinia. In 2017, the target company had over 70 employees and generated sales of €12m. This acquisition fulfilled Fintyre’s development strategy based on dimensional growth, achieving further national coverage. Moreover, in June 2018, Fintyre acquired Reifen Krieg, a German tyre distributor. In 2017, Reifen Krieg had revenues of over €330m. This acquisition allowed the company to achieve significant growth in an international market and continue consolidating its domestic and regional leadership. Furthermore, in December 2018, the company bought two more German tyre distributors, RS Exclusiv Reifengrosshandel and Tyrexpert Reifen + Autoservice, which had a combined turnover of €82m in 2017.

Overall, the company was very successful, with revenues doubling to more than €900m by 2019. Hence, it came as a surprise to the lenders, which typically have the chance to provide rescue financing to keep the company afloat, that the tyre group filed for bankruptcy in 2020. Initially, in February 2020, the German companies of the Fintyre Group filed for preliminary insolvency proceedings in Frankfurt. According to analysts, the insolvency was caused by the insufficient integration of various add-on acquisitions and the fall of winter tyre sales in the months of December and January. Several months later, in July, Reifen Krieg, one of the companies under the Fintyre family, was sold to Tyroo, a domestic rival, for an undisclosed fee. Moreover, by August of the same year, Fintyre was placed under bankruptcy protection by a court in Italy. At that moment, there were discussions about converting its bank debt, as well as liabilities with Blackstone, into equity, as well as converting producers and suppliers into investors. Bain’s entire investment was wiped out, something not uncommon in the world of PE investing. Moreover, the company had debts totalling over €300m and Blackstone’s credit arm was owed €230m.

Three years later, Blackstone is still attempting to recover its investment. They have yet to recover any of the more than €200m initially borrowed and are facing the possibility of a total loss if they are unable to recoup anything through legal actions. There’s a perception among Blackstone senior management that Bain wasn’t transparent in the period leading to the insolvency, which even led to executives from the credit fund to complain to their counterparts at Bain. Currently, Blackstone is paying Pallas, a law firm known for high-stakes litigations, to investigate if they can recover the losses or bring up claims against their rival, Bain Capital. Nonetheless, the possibility of recovering the credit investment is not great as Blackstone sits behind another creditor group initially owed €65m. To this day, the creditor group ahead is still €50m short of receiving their payment, further diminishing Blackstone’s prospects.

Nonetheless, the potential €200m loss hasn’t deterred Blackstone to continue their increased activity in credit. Blackstone has been reshaping their credit arm from some of the initial riskier deals they initially made, and since the Fintyre fiasco both of its European credit heads have left. Moreover, in September 2023, Schwarzman announced that the insurance and credit business were going to be combined to form Blackstone Credit & Insurance, which is expected to grow to manage $1tn in the next 10 years, a significant increase from the current $295m under management for the asset class.

Conflict of Interest from a lawyer’s point of view

Since the early 2010’s, market pressures, along with access to plenty of “cheap” money because of the low interest rates, meant many lenders lacked negotiating power when agreeing to terms with private equity companies. Lawyers and their PE clients, used these advantages to convince lenders, such as the credit arms of other PE’s and Wall Street’s largest banks to agree to lesser safeguards regarding debt levels and dividend payments, as well as to the imposition of designated counsels, on the deals they help finance.

The use of a designated counsel is a legal practice that became common in Europe and in the US after the global financial crisis. It was originally created as a mechanism to make the buyout process more efficient, nonetheless, today, it is widely seen as a potential conflict of interest between parties. It allows financial sponsors, guided by their lawyers, to appoint and even pay the fees, of the law firms that represent the lenders funding their deals. Advocates of this legal figure argue that selecting a single law firm to represent all lenders in a deal, as well as usually working among the same firms, means negotiations are less likely to get delayed by problems between the lawyers. The process gives little opportunity for the lender side to review documents, in the name of efficiency, while cutting costs and getting deals done faster. However, critiques say that this mechanism has allowed PE companies to pile more debt in the company they own and take out huge dividends. Moreover, it makes it harder for lenders to push back when disagreements arise.

Kirkland & Ellis have grown from a mid-sized Chicago firm to the world’s highest grossing law firm with over $6bn in revenues in 2021, largely driven by private equity deals. Since 2013, the firm saw its market share of advisory to European leveraged deals quadruple from 7% to 26.3% in 2022. Its growth is highly attributed to an era of low interest rates, which prompted an increase in investments in private equity because of their nature as a high-return asset class. Some of their employees, such as Neel Sachdev, are known for going above and beyond to ensure the needs of his private equity clients. The firm has earned the reputation of being one of the most aggressive law firms in deal negotiations. Being on the wrong side of a deal with them can result in the counterparts being frozen out of future deals.

Moreover, firm partners, including Sachdev, have gained so much influence that other elite law firms, such as US-based Shearman & Sterling, consult him regarding hiring. In this case, after the latter firm hired their new partner, after receiving advice from Sachdev, they secured lucrative sponsor designated counsel mandates. Furthermore, Sachdev’s influence extends to more firms. US-based firm, Paul Hastings, supposedly asked Sachdev for advice while hiring a team to expand their debt finance business in Europe. In the words of Trevor Clark, a former finance lawyer, and current law lecturer at the University of Leeds, “It is very difficult to feel you have independence when the other firm sitting across the table may have played a role in getting you your job”. Hence, it is possible to make conclusions about the potential conflicts of interests among law firms, as it is somehow evident that the power relationship among the firms might influence the negotiations among the parties.

The deterioration in the global economy has strained the relationship between PE companies and lenders. As inflation has risen, along with interest rates, many highly indebted businesses are facing their first prolonged financial challenge since the financial crisis. Due to owning billions of dollars of loans to companies exposed to the current macroeconomic conditions, details in loan agreements have become much more important. Lenders have become more sophisticated, some even being the credit arms of the PE funds, are now pushing for change. Recently, creditors such as Apollo, Carlyle [NASDAQ: CG] and KKR [NYSE: KKR], began hiring their own counsels, often called shadow lawyers, which are employed to give additional legal advice after concerns about the independence of the appointed counsel began increasing. Moreover, lending groups including Blackstone are now drawing up lists of preferred law firms to act as designated counsel and actively pushing back when certain law firms are appointed for the role. Supposedly, Paul Hastings and Shearman & Sterling’s, firms whose independence is questioned are among the firm’s lenders try to avoid working with.

Consequently, because of the potential conflicts of interest that arise through the appointment of designated counsels, the practice is undergoing scrutiny. The International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) began looking into the designated counsel agreement as part of a wider probe into leveraged debt markets. As the era of cheap money comes to an end, and a period of rise in private credit begins, the designated counsel practice might come to an end, resulting in more guarantees for the creditors, and an overall fairer deal.

Conclusion

The original drivers that sustain private debt growth remain, as banks are hesitant to extend loans to mid-market corporations and struggle to offload debt. Institutional LPs view the private credit strategy as a favourable alternative to fixed income. The high volume of private credit transactions is likely to continue because of current market trends and its appeal to lenders and borrowers.

Within the private credit asset class, direct lending stands out as the biggest modality. From the investor’s perspective, direct lending is particularly attractive due to its high return potential, loss rates that are on par with, if not superior to, public markets and the opportunity to diversify away from conventional investment portfolios. Borrowers, on the other hand, value the straightforwardness and reliability of completing the transactions.

Blackstone is one of the frontrunners within this market and has recently announced efforts to explore further asset-based financing, which consists of a line of credit secured by a company’s tangible assets, such as accounts receivable or equipment. This asset class is especially interesting for companies because as interest rates remain historically high, more companies seek efficiency and leverage their balance sheet to obtain cheaper debt, so many more assets will become financeable.

Another fund well-positioned in the private debt industry is Apollo, whose lending business accounted for $392m, or nearly half, of the firm’s $793m in fee-related revenue received in the second quarter of 2023. The firm is focused on expanding this business line and is negotiating continent-wide distribution with several banks for its recently launched private credit fund for individuals in Europe. Overall, nothing is certain terms of where the private credit market will go, but the growth of the asset class is inevitable in the coming years.

0 Comments