Introduction

We are coming out of a decade in which interest rates have been at historic lows. All investors are looking into new directions to increase their returns. The rise of one asset class has caught a lot of market attention lately. With the advent of streaming, music royalties have a similar payoff structure to bonds. We chose to take a deeper dive into the music industry and explored the opportunities and risks of this alternative asset class.

Industry Overview

The music industry in its current form is a highly complex ecosystem that is composed of a multitude of different participants. This may render it difficult to trace their respective revenue streams. In the following, we are going to give an overview of the major players in the industry and highlight the different segments of the value chain.

First, it is necessary to differentiate between the two types of copyrights involved in the creation of music. One concerns the melody and the lyrics of the song. This may be referred to as the copyright of the song itself and is usually held by song writers or the music publishers that they are represented by. The other form of copyright is commonly called master recording and is owned by artists or their respective music labels. This concerns the actual sound recording of the songs.

Music Publishers:

The function of publishers consists in assisting song writers financially and creatively in exchange for receiving the copyrights for songs that the writers create in the future. They then get in touch with record labels, movie studios, etc. to record and distribute the songs and thus generate revenue. In the process they grant licenses for the sale or broadcast of the masters of the song.

Publishers earn revenue in the form of royalties each occasion the song is utilized by outside parties. A few examples are 1. royalties for each download of the song recorded by music artists, 2. royalties for live performances or broadcasts on the radio, 3. royalties for streams on streaming platforms.

Record Labels:

Record labels help music artists, which they have previously signed, to record masters of songs. They subsequently manufacture the songs and distribute them on the various platforms existing today. They generate revenues from multiple sources, the most prominent of which are: sale of albums and digital downloads, royalties from streaming platforms and royalties from the utilization of sound recordings in movies and television. Afterwards the artists receive a percentage of the label’s revenue as a royalty.

Revenue Sources:

The music industry has undergone major changes in the last 20 years. Up until 20 years ago, it was easy for everyone involved to keep track of how much revenue was being generated in which way. Labels sold physical copies of songs such as CDs through retailers, and awarded recording artists and publishers fixed royalties, which those received a certain amount of time later. Although this medium has diminished over the past years, it still accounts for 25% of recorded sales in 2018.

With the emergence of digital downloads through platforms such as iTunes, it became even easier to monitor cash flows: Apple as the retailer keeps 30% of the price of any song sold on its platform. The rest goes to the label, which, additionally to a percentage of sales that is usually fixed in the contract, pays a royalty to the artist and the publisher. The remainder, usually around 45%, is kept by the record label itself. However, digital downloads have been greatly impacted by the arrival of streaming, which has shifted consumer demand away from ownership of specific songs towards access to a wide range of songs. This will lead to a decline of sales of between 10% – 20% over the next ten years.

Another revenue source is Synchronization. Here, songs are implemented in motion picture productions such as movies or television series. Usually, these deals are set up between a music supervisor and a publisher, where the latter pitches the song to the former and grants them a synchronisation license if there is interest. The publisher then receives royalties each time the music is used. Recently there has been an uptick in revenue from this source due to the growing number of content creators and the increase in consumption that goes with it.

It is needless to say that the music landscape has changed considerably in the past years. Due to the introduction of streaming companies such as Spotify or Apple Music, free music platforms such as YouTube and customizable radio stations such as Pandora it is now far harder for labels and artists to keep track of the money they earn from their songs.

Subscription services such as Spotify have become an integral part of the industry and provide labels and publishers with an important source of revenue. Streaming companies use a series of formulae that are recalculated on a monthly basis in order to determine a label and publishers’ share of the revenue. Factors that are considered are Spotify’s subscriber numbers and the artist’s popularity, amongst others. Because of the complicated nature of these calculations, the uncertain regulatory environment and the tiny amounts of the royalty payments per one stream, it is still uncertain how much revenue can ultimately be generated from these platforms in the long term.

Another new format, YouTube, falls under the broader category of performance right platforms. On this platform copyright holders are entitled to a share of the revenue YouTube generates from ads on videos that use the copyrighted material.

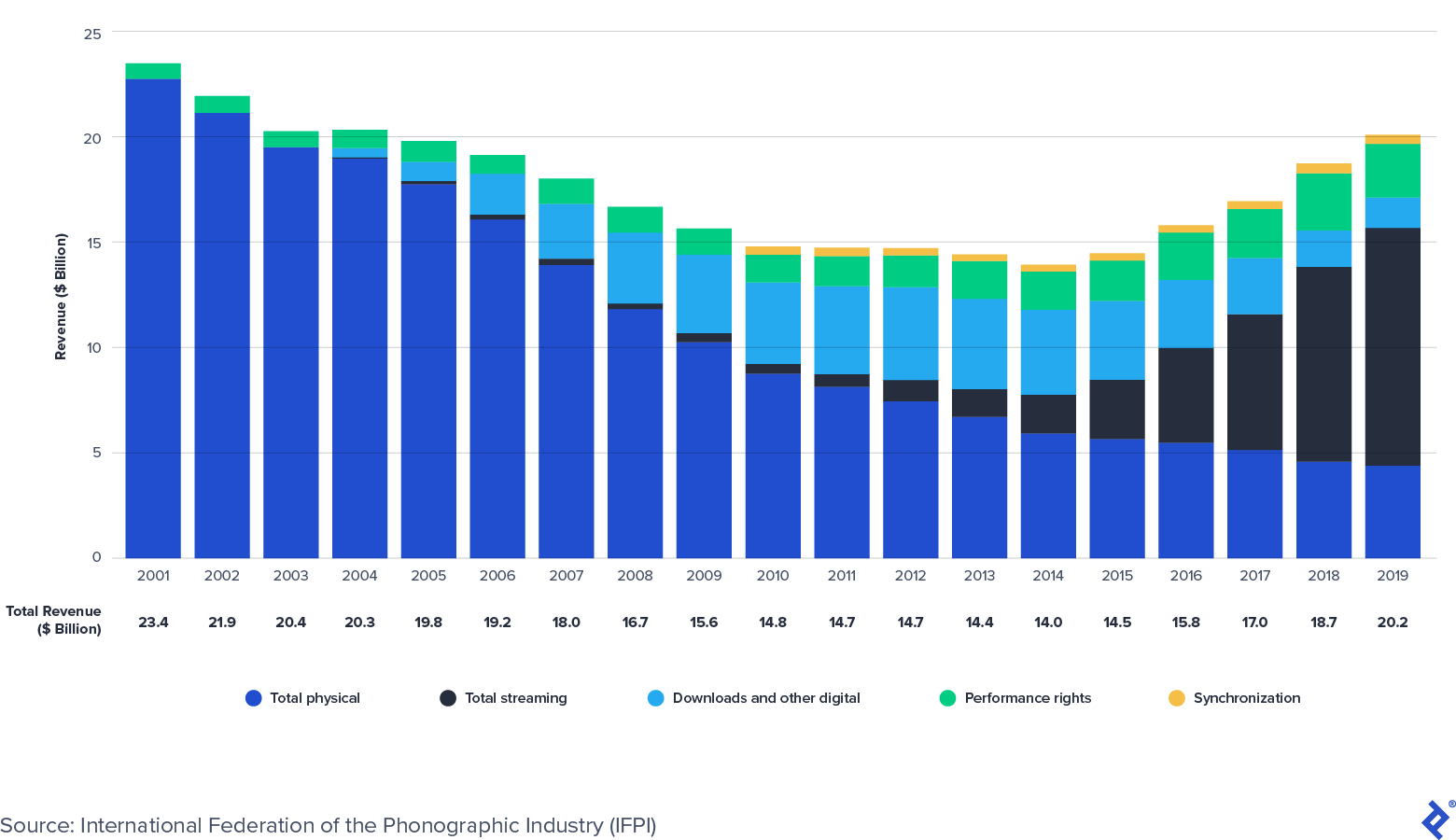

The appearance of new means of music consumption has certainly disrupted some traditional means of consuming music but the overall impact has certainly been a positive one. In effect, the total revenue in the industry has been declining ever since the high of $25.2bn in 1999 due to the rise of piracy and platforms such as Napster. In 2014, a low of $14bn was reached. Since 2015, however, the music business has been back on the growth path, largely thanks to the increased accessibility of smartphones coupled with the rise in streaming services. This combination succeeded in breathing new life into the lethargic industry and helped it reach revenues of $20.2bn in 2019. The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) reports that streaming revenue grew at a 42% CAGR from 2015 onwards while the whole industry’s CAGR sat at 9%. The graph above illustrates how the growth of streaming has counteracted the decline in other formats of music.

Trends in the Music Industry and Financial Markets

Recently the industry has been changed by the advent of streaming. This disruption does not only change the way of how consumers interact with artists, but it also changes the cash flow structure of song royalties. Traditionally, royalties generate income when another artist performs the song, it is played on the radio, or when someone purchases a physical or digital copy of the song. Therefore, the traditional payoff structure of royalties is very front heavy. They usually generate a majority of their cash flows between three and 12 months from its release. From that moment on it constantly decreases.

The rise of streaming and social media apps changes this because it creates more stable revenue in the tail-end of the payoff structure. While traditionally the tail-end payoff would be very small and unpredictable, streaming services generate a stable and sizable stream of revenues. These tail-end cash flows are surprisingly resilient. During the pandemic, revenues from live performances took a major hit, but streaming revenues were unaffected. Thus, an older song has a payoff structure that is similar to a bond. This made investing in this asset-class very interesting for many types of investors. Mutual funds, hedge funds, and even private equity groups are looking into this direction as the yields of traditional assets fluctuate around historic lows due to the current interest rate environment. Private equity houses even profit from the low-interest rates to enhance yields with leverage.

Due to this new dynamic, activity in the royalty market has risen sharply. Private equity shops such as KKR and Shamrock Capital have put sizable bets in this asset class. The former just announced in January that it had bought a majority stake in Ryan Tedder’s music catalog for an undisclosed amount. The latter made the headlines for purchasing a portfolio of Taylor Swift songs for $300m in November 2020. Nevertheless, one market participant stands out above all others. The closed-end fund Hipgnosis (LSE: SONG), has been in the headlines a lot over the recent years for its aggressive deal-making. The fund’s only asset class is music royalties, which it has been snapping up in a series of very aggressive deals since its inception in 2018. Starting February 10th, 2021, the fund is issuing new shares to raise a further £605m to widen its music catalog.

So far, the fund has delivered on its promise of yields. The Hipgnosis fund is sustaining a 4.15% dividend yield. Nevertheless, it has come under fire for a lack of transparency. While the revenue stream from royalties is rather stable, their market value is hard to determine. Royalties are not standardized, and the market is not active enough to deliver accurate and up to date valuations. Thus, the valuation of such assets can be highly subjective, and details of transactions are rarely disclosed. This extra layer of risk scares away more traditionally-minded investors.

In addition to publicly listed funds, private investors also can invest in royalties directly thanks to a platform called “Royalty Exchange” which acts as an intermediary. It is an online auction house where people can buy and sell shares of royalties. The platform has existed since 2013 and it claims that the average return on investment for their customers was greater than 12%. This asset class might be interesting for anyone who is looking for a way to diversify their portfolio.

The increasing number of specialist funds to invest in song catalogues and the surge in investor demand for such investment vehicles can easily be explained by the attributes of this new asset class. Investing in royalties brings advantages such as attractive relative yields, stable and recurring income, and limited correlation to broader economic activity.

How is music valued?

The valuation of music catalogs needs to take into account different factors: the essential characteristics of the music catalog, such as the list of songs and the publication date; any relevant agreements in the recording and publishing of the music catalog, such as advances and licensing agreements; and, probably most importantly, the annual royalties earned as well as the spread of the royalties across each song of a catalog. This information will be used by interested funds to estimate the music catalog’s future cash flows that will generate revenue for their investors.

The information is usually combined in the three most popular valuation approaches:

- The Market Approach is used if the royalties are expected to remain constant every year, or near to a recurring average. Through this approach, a range of market multiples is created through financial ratios of similar industries’ assets. The types of market multiples used usually are:

- EBITDA: the classic key financial metric calculated in the income statement and used for valuations at the company level… In the last 15 years, this multiple has been increasing on average from 10.0x to 20.0x in publishing, but had been decreasing until 2013 from 19.0x to 7.0x for recording labels. After 2013, EBITDA multiples were not considered relevant for recording labels, as these grew massively due as the uprise of the streaming services shifted most of the investment from publishing to their end of the process, and most valuations from this moment on were made at catalog level using NLS.

- Net Publisher’s Share (NPS) and Net Label’s Share (NLS): these two financial metrics, instead, allow to make a catalog specific valuation. The NPS metric analyses the revenues and costs of the music composition stage, and it is calculated by taking the gross royalties generated by the catalog and subtracting writer royalties and administration costs. The NLS metric, instead, analyses the revenues and costs of the recording stage, and it is measured by subtracting artist royalties and manufacturing and distribution costs from the gross royalties. In the last 15 years, the NPS and NLS have ranged on average from 7.5x to 16.0x and from 6.0x to 12.0x.

In the Music Industry, these market multiples are affected by various factors, such as remaining copyright lifetime, an international outreach of intellectual property rights, the uprise of new recording technologies, and more. Commonly, multiples range from 5 to 15 but can be lower or higher due to competition or non-exclusivity of rights. Once determined, the market multiples are used to estimate the value of the music catalog based on the future estimated average annual royalties. For example, if the average royalties are expected to be $1M annually, using a multiple of 6, the value of the music catalog is simply $6M (1M x 6).

- The Income Approach is used, instead, when future royalties are expected to vary through time and the copyright period can be reasonably predicted, and it essentially takes a model from the Discounted Cash Flow. It is appreciated that estimating music popularity is complicated, so a common helpful rule is to take into account between 5 to 7 previous years of royalties and their trend. This method will take into account the life of the asset and two main rates, the market-derived discount rate and the diminution factor. The discount rate is used to approximate a present value from future estimated royalties. The diminution rate, instead, gives an estimation of how royalties will increase or decrease year by year. The latter is developed by considering the popularity, size, concentration of earnings and copyright termination rights. Through these two rates, the Income Approach reflects more completely the risks of owning a music catalog.

It is also possible to assume that the popularity or royalties of a catalog decline at an exponentially changing rate. In this case, we can adopt the Regression Model, provided that we also assume that the peak is reached during the first or first two years. This model can in some cases allow for a more realistic cash flow analysis from a catalog considering different copyright lifetimes.

- The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) Approach is used when the IRR is taken into account, which expresses the return rate that justifies the total cost of an asset, and it is subjective to each valuator. If a catalog was to cost $1M and have $20’000 NPS over 10 years, then the investment IRR is 20%. However, if an investor can only accept a 25% IRR, then the maximum he can pay is $800’000. Hence, using this approach the valuator back-solves its valuation price by fixing its IRR. In a bid using this approach, the bidder who can accept the lowest IRR is going to win the bid. If the catalog is paid using debt, the IRR will have to take into account also the interest on the debt, lowering the maximum purchase price.

What factors impact music valuations?

The drivers and risk of valuation can be easily summarized into few which affect the market multiples used:

Catalogue specific:

- Fluctuation of cashflows: generally, investors prefer stable streams of income that typically characterize the so-called “evergreen” songs. If instead, the cashflows of a catalog are very volatile over the years, the catalog’s value decreases. It is imperative to keep in mind that past royalties are predominantly important, any incorrect recording of this information may lead to the undervaluation of the music assets.

- Number of songs: the number of songs in a catalog and the degree of concentration of royalties on a specific song can lead to a different valuation. Generally, the higher the number of songs and the diversification, higher is the value attributed to the catalog. For example, a catalog which derives most of its royalties from a particular song is generally considered riskier and less valuable than a catalog that derives its royalties more equally across all songs.

- Duration of copyright: the remaining life of copyright is key to any valuation approach, to predict the number of years a catalog can generate cash flows. The copyright duration can also be threatened by legal procedures, for example, by an heir of a late artist who can exercise his right to revert ownership of copyright. So a probability of this happening must be accounted for.

- Level of control: some catalogs are usually controlled by more than one entity, such as the artist and the label. If an asset was to be sold, the price would be higher the lower the number of entities that share control over it.

Macro Factors:

- Precedent Transactions: they can set an average market multiple to be used in the market approach.

- Scarcity and Competition: the merger of publishers or recorders and the tightening of the respective markets can lead to higher valuations as fewer competitors know that each catalog or writer can make the difference to the market share controlled. While the entrance of new players in the publishers and recording marketplace can either drive valuations down, or in the case of rich hedge funds entering the market, the valuations could increase as these need a high level and high return catalog or writer to keep the money flowing from investors to the hedge fund, and hence are ready to pay more.

- Streaming Growth: music valuation is obviously tied to music consumption, which increases by an average of 15% annually. This growth is driven by streaming services, whose popularity grows approximately 27.5% annually, as other types of music consumption lose popularity. Hence, appreciation of music valuation is tightly tied to streaming growth.

- Interest Rates: recent low-interest rates led to higher yields of stable music publishing income, increasing interest by large corporations and funds.

- Regulation: the existence of, for example, Consent Decrees, in which the Department of Justice imposes restrictions on how a music owner can license or sell its content, due to previous violations of the law. For example, in the U.S. most important music publishers such as ASCAP and BMI are governed by this decree.

Forecast:

However, royalty funds are by no means riskless. First, there exists the possibility of valuing a catalogue incorrectly and ending up overpaying. This danger is exacerbated by the fact that income from music royalties usually quickly declines in the first few years after the release of the song before leveling off. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the age of the respective catalogue before investing.

Another factor to consider is the inflation risk. Research has shown that royalty rates do not immediately respond to changes in inflation. Indeed, they seem to devalue against inflation.

Additionally, there is regulatory risk. Since companies such as Spotify and YouTube are relatively young, the regulations regarding the copyrights of musical composition on those platforms are still being developed. Although decisions about this subject up until now have been mostly in favour of copyright holders, it is still worthwhile to observe future developments in this area.

Lastly, investors are advised to be wary of funds such as Hipgnosis, which are characterised by a lack of transparency or more precisely, an unwillingness to disclose cash flows. Because Hipgnosis is constantly acquiring new royalties, which in turn bring in fresh cash flows, it is hard to estimate its long-term financial performance once this spree of acquisitions is over.

1 Comment

Dave · 27 January 2024 at 10:08

Really great report, lots of useful info and synthesis of the entire landscape!