Private Equity Industry Overview

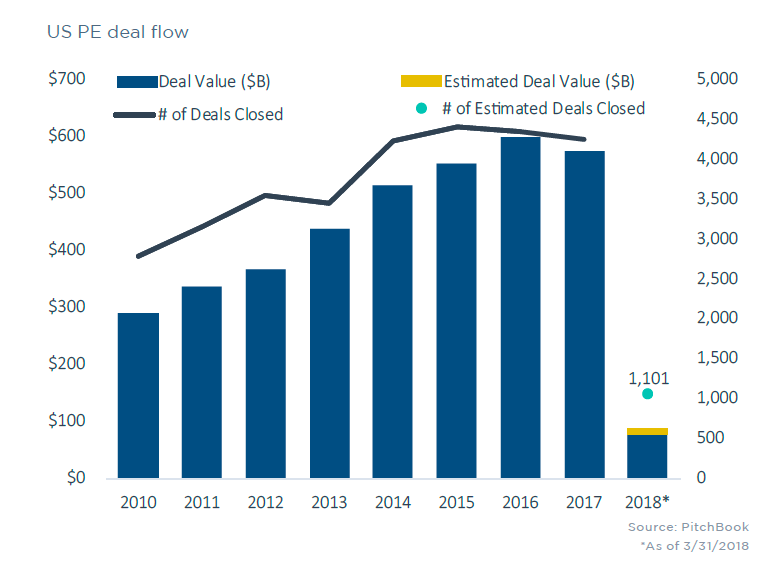

Private equity is like home flipping, but with large corporations instead of dilapidated houses from the 1970’s. Only rather than having profits in the tens of thousands, it’s in the tens of millions. The private equity industry, pioneered in the 1970’s by the likes of KKR and Apollo, has grown to encompass everything from firms focused on distressed investments, to turnarounds, and even industry consolidations. However, the model used to facilitate these different strategies remains the leveraged buyout, a classic tenant of any successful private equity firm. After purchasing an undervalued company through an LBO, the buyer will increase profitability through cost cutting techniques and value creation, ultimately hoping to exit 5 years later at a higher price than that of their purchase. While this industry has always been marked with profitability and growth, recent trends have pushed its expansion at a pace not seen since the eve of the 2008 financial crisis. Fundraising is coming close to hitting the record $262bn raised in 2007, as PE firms managed to pull in $242bn in 2017. The middle market continues to dominate the allocation of this funding, accounting for nearly 79% of all funds’ investments. The industry is also seeing a return to mega buyouts, such as KKR’s acquisition of Envision Healthcare for $10bn, that defined the industry in the months leading up to the 2008 recession.

Private Debt Industry Overview

Prior to 2008, private debt was regarded as a non-core asset class in the usual institutional investor’s portfolio. However, since then it has gained momentum because of two main sources. The first source was Directive IV under Basel II, which introduced a series of capital requirements that forced banks to exit risky investment on their loan book in an effort to fortify their capital base after the 2008 credit crunch. The second was Europe and USA’s Q.E. programs, which propped-up the values of equities and bonds; thus, driving investors’ search of decent yields into untraditional assets. Private debt, the debt accumulated by individuals or private businesses, is a fundamental funding component for fast growing, medium-sized companies. The loans are characterized by a final maturity date, a fixed return stated in the contract, a customable set of terms, and frequent use of collateral assets to protect investors. Both parties benefit in private debt: investors from attractive interest rates and borrowers from access to capital without strong covenants required by banks. Therefore, the private debt industry is growing rapidly, with Prequin, and other agencies, reporting that private debt funds have increased fourfold over the last decade up to $667bn in total value in 2017, with forecasts expecting growth to $2.5tn during the next decade.

Composition

There are several types of private debt funds with their own respective characteristics. Direct lending is the most common type of debt, representing 51% of capital in the private debt industry, followed by distressed debt with 21%, special situations with 13% and mezzanine with 11%. Direct lending consists of loans to companies without intermediaries. Mezzanine loans have embedded warrants which increase the value of the subordinated debt and allow greater flexibility when dealing with bondholders. Distressed debt are loans to companies that are either in bankruptcy or on the verge of it. Finally, special situations are loans in which a particular contingency compels investors to raise debt, thus requiring specific features. This category encompasses a wide range of financial operations going from restructuring, which often deals with the purchase of equity from liquidating shareholders, to temporary capital, which mainly consists in bridge loans.

Profitability

Pension funds and insurers, having seen returns diminishing for over a decade with interest rates next to zero, have decided to enter this highly profitable new asset class by investing in private debt funds. Indeed, with returns exceeding 5% over every 5 years since 1992, private credit funds appear to be a reasonably lucrative investment. Furthermore, recent data from Preqin demonstrate how top quartile private debt and median funds present a high net internal rate of return (IRR) of around 16% and 12 %, respectively. Even bottom-quartile funds are performing reasonably well in contrast to private equity, where returns are heavily dependent on the manager’s pedigree.

Private debt’s remarkable steady growth has resulted in a fourfold increase in AUM from $147bn in December 2006 to $667bn in December 2017. The majority of investors are based in North America (55%), followed by 25% in Europe and 14% in Asia-Pacific. However, it is the European private debt market, a much younger space than its North American counterpart, that is experiencing the quickest growth. While US private debt funds have grown by $10bn in 2018, from $83.7bn to $92.8bn, European funds grew by $20bn, from $39.1bn to $59.3bn, during the same period.

Current situation

Like many other current trends in finance, this new wave in risky lending was driven by catalysts put into place by the 2008 financial crisis. Following the collapse of major financial institutions and the recession that ensued, a wave of regulation and cost cutting affected many banks. In response to this, credit institutions’ lending levels notably shrank, reducing their risk appetite for less credit-worthy borrowers and high-yield debt. A gap was created in the market for those companies in need of financing, but unable to obtain it through traditional institutions, because of their highly leveraged capital structures and poor credit ratings. Rather than letting potential profits go unclaimed, private equity firms such as Apollo and Blackstone began to fill the gap by creating their own direct lending businesses. While at the beginning these private credit funds within PE firms were merely a small side-business, they grew to become the main business lines for 3 of the 4 largest private equity firms. Aptly dubbed the “shadow financers” of America, these private equity firms now raise more than $65bn for their private credit businesses each year, with 2018 expectations expected to beat $80bn.

Actors

A selective group of 5 of the largest PE firms have come to dominate the space, letting their collective risk appetites and agendas transform the market into a riskier space with every passing quarter. Apollo, Blackstone, Ares, KKR, and Carlyle have steadily grown their direct lending business through the partnership or acquisition of Business Development Companies (BDC’s) that were already established in the private credit space. Ares Capital Management, the pioneer in private equity direct lending, manages more than half of its $121bn in assets through instruments like first lien loans, CLO funds, and uni-tranche loans. However, the company that has implemented the idea the furthest is Apollo, which created a proprietary insurance firm with the sole purpose of reinvesting its entire balance sheet back into its direct lending business. While the risk of investing billions of dollars into BDC companies may seem great, many of these PE firms have been handsomely rewarded by their venture, with returns averaging 5% over 5-year periods.

Leveraged Loan industry

Increased risk taking in the private debt market is focused heavily on a segment that is already considered one of the riskiest: leveraged loan market. It consists of all private loans, usually tied to the 3-month Libor interest rate, made to corporations that already have large amounts of debt (over 4 times EBITDA) and poor credit ratings.

While it may seem like a poor idea to include in this market less and less credit-worthy borrowers, those investors with large risk appetites don’t seem to be bothered. Just over the past year, U.S. companies with credit ratings in junk territory took out $564bn in commercial leveraged loans. The leveraged loan market size jumped to $1tn over the past decade, making it nearly as large as the junk bond market. This expansion is being fueled by creditors offering covenant-lite loans to borrowers, making it easier for risky corporations to take on huge amounts of debt by simply lowering the proverbial bar. Covenant lite loans are defined by their lack of requirements on the borrower, an aspect that used to protect the leveraged loan market from severe losses by giving greater power to creditors. While these covenant-lite loans may provide higher yields, they also reduce the average amount creditors can recover by anywhere from 20% to 60%, making it even more difficult to recover in the case of widespread defaults.

Considerations for the future

Investor appetite

The private debt investors are keeping a bullish outlook in spite of the alarms. The lucrative rates of returns have exceeded investors’ expectations and a generally optimistic view about the future reigns in the industry. Indeed, according to a Preqin survey conducted in Dec 2017, 36% of investors are likely to increase their allocation to private debt in the next 12 months. 19% said that they would increase their allocation significantly and 31% said it would remain the same. Moreover, private debt dry powder has been steadily increasing over the last 10 years and surveys suggest that the trend will continue to do so as long as the quality of the debts does not worsen.

Sustainability of the private debt market

For the last decade, and especially nowadays, it has been extremely easy to raise capital for private debt funds. The demand is so high that managers do not always come across investment opportunities to meet the investor’s demand, leading to remarkably high dry-powder funds of around $160bn in the US at the end of 2017 and $80bn in Europe during the same year. In the case of non-invested capital, investors will evidently be dissatisfied with the private equity and switch to another firm that will be able to invest. As consequence the private equity firms are, as a general trend, accepting riskier loans with fewer covenants to be able to meet the demand of investors. Indeed, strong covenants are now attached to around 23% of leveraged loans written in the US, a much less significant fraction than the 40% of 2015 and the 80% of 2007. By doing so creditors are losing power to intervene whenever a management team behaves improperly or a firm’s profits drop.

Systemic outlook

Private lending’s current highly delicate environment was created by low interest rates, fast growing companies and fearless creditors. However, previously enthusiastic investors now find themselves facing the risk of systemic default because of the bubble-like market growth. One of the most prominent risk factors is the global deterioration of debt quality and how it could have rippling effects in the case of an economic downturn. Since the 1970’s, the median S&P corporate credit rating has gradually declined from an A grade rating to near junk territory levels. Rising levels of corporate debt came in tandem with this drop in credit scores. In the decade since the financial crisis, corporate debt levels have skyrocketed from $38tn to $56tn, making up nearly 31% of the $57tn increase in global debt since 2007. But an even greater concern for creditors than this quality deterioration is the chance of rising interest rates. US monetary policy is moving towards increasing interest rates to slow down what many consider an overheating economy. However, the direct lending market thrived in a low interest rate lending environment, arguably the most forgiving for borrowers trying to finance projects and long-term investments. Should these interest rate raises be implemented, companies with faulty credit ratings, such as those being lent to by PE firms in the middle market, are at risk of default if they are unable to refinance at the higher rates. Additionally, the lack of covenants on leveraged loans reduces the amount creditors can retrieve from first and second lien loans. To make the situation even worse, the money lost in case of default will not just affect the bottom lines of private equity firms, but also that of pension funds. Nearly 90% of pension funds have 5% to 15% of their funding invested in the leveraged loan market because of its potential for high-yield, steady returns. The political implications of losing retirement money meant for hardworking Americans—many of whom work in lower paying positions within the federal or state governments—would be disastrous. If a sizeable chunk of pension funds is lost in the case of a downturn, PE funds could face punishment and regulation in the same manner that financial institutions did following the financial crisis.

Regardless of the previously mentioned concerns, critics of the leveraged loan market are divided on whether it poses a systemic risk to the economy. Many stakeholders, specifically creditors, argue that leveraged loans don’t pose a systemic risk because the industry is too isolated from other important aspects of the economy. Corporate defaults would affect the profits of their creditors, but ultimately stop there. While the investors backing these creditors, namely pension funds and insurance agencies, would also be affected by the losses, few funds have more than 15% of their total AUM allocated to PE funds. On the other side of the spectrum, critics believe that the risk originally taken on by banks has simply been transferred to a less regulated part of the market. Former US Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen believes that the repackaging and sale of these leveraged loans through CLO’s, much like the CDO’s of a decade earlier, could cause a market crash due to their lack of regulation. But regardless of critics’ beliefs, the crash of a $1.3tn market would be no small hit to the financial system; the only question that remains is how expansive and scarring its fallout could be.

0 Comments