Introduction

Restructuring is the process of advising distressed companies (those in the midst of bankruptcy, or rapidly approaching it) in order to help them change their capital structure to get out of or avoid dissolution. This can be achieved by modifying their debt, operations or structure. Outcomes of this process range from distressed sales to refinancing scenarios, but this article will focus on bankruptcy procedures. Restructuring deals tend to differ from normal advisory work because they are more complex, involve more parties, require more specialized or technical skills, and have to follow bankruptcy legal code. In order to provide a quick overview of what restructuring is, prior to addressing the more technical and legal aspects regarding these transactions, we will cover a quick restructuring case.

Restructuring case

The best and easiest way to review a potential restructuring scenario is through a simple example. The following example is highlighted in the book Distressed Debt Analysis: Strategies for Speculative Investors, as well as in the Wall Street Prep restructuring guide. This is a purely fictional scenario meant to highlight the various steps that lead to a potential restructuring transaction, and ways in which they can be resolved.

Step 1: I decide to buy a house as an investment that I can then rent out to tenants. The house cost me $950k and I decided to also have $50k on hand for additional renovations, accounts payable, etc. After incorporating a company for this new business venture, I use $500k of debt and $500k of equity to finance the purchase and my slush fund. For simplicity’s sake, we will assume that debt is senior secured and trading at par, while equity represents 100k shares priced at $5 per share.

Step 2: After setting up my property and getting some tenants, I decide to complete some renovations in the hope of improving the value of my property. I need $150k to do that, and decide to raise the money by issuing more shares. During this process, I retain an investment bank as my advisor, and they tell me that my business has a post money equity value of $900k due to the value of my property increasing in the housing market. Due to the influx in the share price to $7.50 (representing the increase in equity value), I now need to issue an additional 20k shares at that price to get $150k. As the market value continues to diverge from the book value (GAAP), it is important to have an understanding of how the two differ.

Step 3: Due to these renovations, I can now charge higher rent on my property. Equity investors appreciate the positive changes I’m making to the business and increase my share price to $10. While this represents a surge in the equity value of the company, the GAAP based balance sheet remains unchanged, as GAAP does not record shifts in market value.

Step 4: Investors have praised my strategies thus far, and I decide that it is now a great time to expand my properties with an acquisition strategy. There is a portfolio of investment properties that I believe would be a great purchase, however, they are in a geographic area where I don’t have experience. The business portfolio will sell for $200k, however, they’re GAAP based value of assets is only $20k. This is similar to my own balance sheet, where GAAP and Market based values diverge to a significant extent. Rather than issuing more equity, I decide to take on a subordinated loan to finance the transaction. The $180k difference between the book value of the acquisition’s assets and the market value we buy them at is recorded as goodwill on our GAAP balance sheet. Investors love the strategy I’m taking and the share price increases to $15.

Step 5: Unfortunately, my good luck didn’t last much longer. Due to a combination of macroeconomic and company specific issues, the market is now valuing the business at $0.10 per share, while the senior debt trades at 50% of face value and the subordinated debt trades at 20% of face value. At this point, we would like to show a blended balance sheet to highlight that debt is a contractual obligation, so the full value must be paid even if its market value drops to become significantly less. Equity, which represents shareholder’s equity and not the market cap, becomes negative. While this may seem rather odd, this is actually an extremely common attribute of restructuring transactions. Other things that could lead to the market becoming “unexcited” about the firm’s prospects include industry specific issues, such as what happened during the 90’s tech bubble. Notice also that the GAAP balance remains the same, but once the restructuring transaction begins any goodwill will need to be written down the zero, and the market’s value of our PP&E will also need to be revised.

Step 6: In our final step, the company has entered into a restructuring process with a financial advisor. In this case, one outcome could be proposing a debt to equity swap, where the senior lenders will exchange a portion of their debt to become future shareholders in the company. The face value of our liabilities is reduced from $700 to only $290, to match the current market value of the company’s assets. Senior lenders will be able to recover a portion of their money through a debt reinstatement, and another portion through a debt to equity swap. In this case, subordinated lenders will get no money, because those creditors senior to them were not able to recover the full amount of their investment. This is a good example of the absolute priority rule, which stated that claims must be handled in their proper order, beginning with DIP Financing, and ending with equity holders. Another important thing to notice about this transaction is that the senior lender must be satisfied with recovering a portion of their investment in equity in the new company. The reason why is simple: a capital structure is unsustainable if it is composed of only assets and liabilities. There must be some form of equity in the new corporation to prevent it from being overlevered in the future, and to ensure that it has a sustainable debt balance moving into a new period of operations.

While the outcome above would have worked, there are also many other outcomes that could have complicated the process we just mentioned. For instance, if the senior lender did not want to increase their involvement in the company (by becoming shareholders in a new corporation), they could have petitioned a court to take over the restructuring process. The subordinated lender, who in this solution would have gotten nothing, is most certainly going to petition a court to take on the case in an effort to gain some of their original investment back. Another solution in this case would be to use an excess cash on hand to pay down the outstanding debt (which in this case is trading at a fraction of its original value). Another complicating factor that could arise is the provision of DIP financing to the company, which would then become the most senior debt in the capital structure, thus moving the current senior creditors into a position where they would be unable to recover as much of their original stake.

Ultimately, restructuring deals are highly technical transactions that can result in a wide variety of different outcomes. To be a restructuring banker, it is essential to have a strong grasp of debt facilities, capital structure mechanics, and legal proceedings.

Out-of-court restructuring

An out of court restructuring occurs when the parties involved in the company judge it is unable to return to normal operating activities outside of bankruptcy.

This solution is often referenced as a “workout” and can allow debtors and creditors to reach an agreement to adjust the company’s obligations. While is it considered a is a nonjudicial process, the final “prepack agreement” often needs to be enforced through a formal court order, especially if there are dissenting creditors.

For this process to be effective some conditions must be met. Firstly, all parties need to be willing to actively cooperate and reasonably accommodate others. However, a number of complications often arise when one lender (senior secured typically) is reluctant to increase their exposure to a financial troubled business, especially when other options such as distressed sales are available. Secondly, the number of parties involved must be limited to ensure smooth cooperation. A high degree of trust and a basic agreement plan are also required for a positive outcome.

Debtholders may decide to pursue this kind of solution because it is quicker than a Chapter 11 restructuring, and they generally gain bargaining power compared to bankruptcy procedures. In fact, it is often the company’s threat of filing for bankruptcy that forces a restructuring agreement and allows the firm some leverage over their creditors. In case bankruptcy is filed, creditors become subject to the authority of a court and of different stipulations allowing nonconsensual modification of claims.

The following are a number of factors that could encourage debtholders not to involve any court in the negotiations:

- The debtor could raise new money senior to the bank (DIP financing)

- If the secured creditor is “adequately protected”, the court could allow the sale of its collateral by the debtor and relating proceeds to be used in the ordinary course of business

- The judge may approve a POR which was rejected by the bank on the condition it is “fair and equitable”

- The debtor could start a litigation which might result in liability or lower priority of the creditor’s debt

- The Creditor could lose a portion of its priority and the right to post petition interests

- As a result of automatic stay, the creditor would not immediately obtain its collateral whose value would decrease over time

In-court restructuring

We speak about in-court restructuring when bankruptcy is filed whether voluntarily (by the debtor) or non-voluntarily (by the creditor). In particular, under Chapter 11 all creditors are forced into a court regulated by the Bankruptcy Code. This ensures greater protection from creditors through forced concessions by the court and at the same time, it makes business disruptions more likely as confidence in the company by its main shareholders is lost.

In case of a filing, timing is key. It can be managed to conserve cash to ensure flexibility during the process and to obtain new financing notwithstanding high risk of default (DIP financing).

Once the company enters the zone of insolvency, fiduciary duties are owed to creditors. In fact, pursuing the interests of equity holders would mean to take on too many risks. As usual in case of bankruptcy they are wiped out in most cases and the company only has one option: going all in to try and restore normal operating activities.

With regard to the business management, the company will act as a debtor-in possession. This means it continues to dispose of its assets as long as the interests of creditors are “fairly protected”. Finally barring fraud or gross mismanagement, management will typically stay in place managing operations day to day alongside a turnaround consultant. After the company goes through this restructuring scenario, it typically will present a plan or reorganization for a vote by all creditors.

The plan of reorganization (POR)

This document identifies what will happen to the company assets, liabilities and equity upon exit from the bankruptcy procedure. The proponent of the plan, often the debtor which is granted the exclusive right to present a plan within 120 days of filing, prepares a disclosure statement to solicit creditor acceptance of the plan containing information about the debt and the effect of the plan. The POR is composed of two substantive parts: the classification of claimants by commonality of interests, where each class contains claims that are similar in terms of priority, and the securities each class will receive upon exit from the bankruptcy procedure.

Sometimes, the debtor and creditor negotiate a plan prior to bankruptcy filing and vote on the plan immediately upon filing as a way to accelerate the process when there is substantial cooperation between parties. This is called a pre‐packaged bankruptcy (or “pre‐pack”) and dramatically reduces the duration of the bankruptcy process – often to less than 45 days.

Determining the size of liabilities is a key part of the POR, because it determines the tier of claimants in different traches of liability. In determining the size of liabilities, the bankruptcy code enables debtors to eliminate or reduce some of them: in particular, executory contracts, such as unexpired leases or retiree benefits, and collective bargaining agreements can be rejected and damages are limited; moreover, legal claims can be valued and capped in the context of bankruptcy, preventing future uncertainty.

As part of the POR, the valuation of the company’s assets is central. Indeed, under the absolute priority rule, priority claims must be paid in full before lower claims can be considered. Therefore, a low valuation can exclude sub lenders from their claims in the reorganized company. Except in pre-packaged bankruptcies, courts must approve disclosure statement before it can be sent to creditors; at this point, their scope of review is limited to whether the disclosure is sufficient to enable creditors to make an informed vote.

Once the plan is approved by court, it is sent to the claims’ holders. Unimpaired holders are assumed to accept and are not solicited, while claims holders receiving no recovery are assumed to reject. Impaired classes that are receiving some recovery are the ones that actually vote. For a class to accept the plan, more than 50% in number of claims representing more than 66.6% in amount must vote in favor

Priority and management of credit risk

In order to define the priorities of the creditors’ claims, it must be determined if the claim is allowed in the first place. Unallowed claims include post-petition interest on unsecured debt, “unreasonable” legal fees, claim of a real estate lessor for damages over a certain amount and limited employee termination claims. Allowed claims are then grouped into classes in accordance with commonality of interests. The main two classes are secured and unsecured claims. A claim is considered secured for the portion of this that does not exceed the value of the collateral; the remainder becomes an unsecured claim.

Claims are then ranked on a priority basis and receive recoveries in accordance with the absolute priority rule. Generally, this claims waterfall looks like the following:

- Super priority secured claims: this class include DIP loans and administrative payments related to the plan of reorganization, such as professional fees

- Secured prepetition claims: claims secured by liens on debtor assets

- Administrative claims: unsecured claims that receive priority over all other unsecured claims

- Priority unsecured claims: unsecured claims, such as accrued employee wages, that receive priorities in the bankruptcy code

- General unsecured claims: typically, the trade creditors or unsecured lenders are in this class

Credit risk is generally determined by leverage, priority and time, but, in distressed debt analysis, priority is critically important. It can be segmented in grants of collateral, contractual provisions, maturity structure and corporate structure.

Collateral is usually granted through a separate security agreement and it is critically important because it gives secured lenders a priority claim on the assets of a firm.

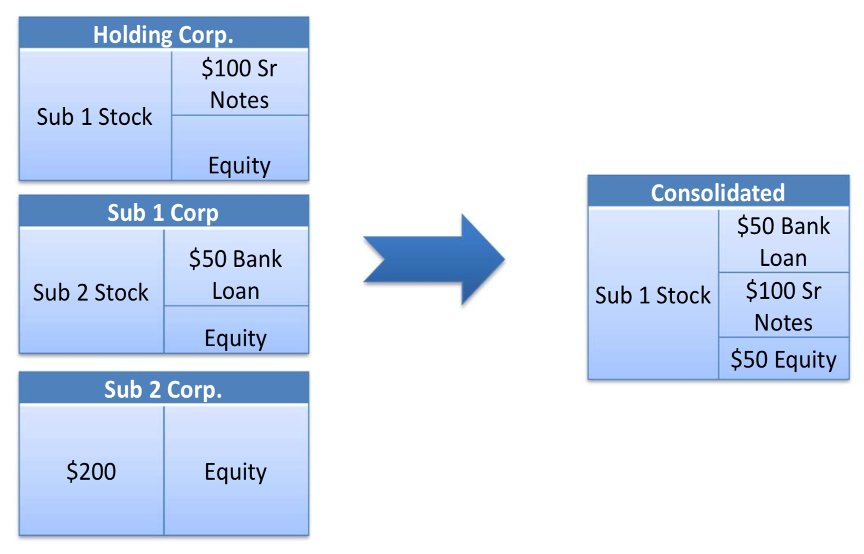

Through contractual provisions, included in an intercreditor agreement, one creditor agrees to subordinate its claim relative to another. Typically, intercreditor agreements will precisely specify the securities that the loan is subordinate to, rather than a broad subordination, implying that the senior claim has no priority claim over other unsecured claims. In the image below, it is shown the effect of subordination on recoveries.

Maturity structure adds a level of complexity to the priority issue because subordinated debt could be due prior to senior debt, whose payment would erode credit support to the senior lender. Senior creditors, in order to protect their claims, should put restrictive covenants on their lending agreements or they could sue the debtor, using a fraudulent conveyance argument.

An investor may require that an existing creditor subordinate its debt, as a condition of funding, and this creditor may as well refuse to do so. However, depending on a company’s corporate structure, this consent is not expressly needed. In case of multi-tier corporate structures, if the new debt is issued by a subsidiary, it is senior to the pre-existing debt issued by the holding company. A creditor may protect its claims by requesting guaranties, when they are available, from the operating subsidiary and from the holding company.

Source: Wall Street Prep RX guide

Finally, covenants are an important tool used by lenders to manage credit risk. Some typical covenants are leverage (Net Debt/EBITDA), performance covenants (coverage ratios), put rights and forced call in the event of a downgrade. As priority is concerned, typical covenants are limitations on spending and negative pledge, that means the borrower is required to include lender in any subsequent grant of a security interest.

Debtor-in-possession financing (DIP)

After the petition has been filed, financing may become available to the debtor in forms of debtor-in-possession financing (DIP). In particular, under the bankruptcy code section 364, debtors can obtain financing during the bankruptcy process, as long as original secured creditors are adequately protected. The methods of providing “adequate protection” to existing creditors are specified under bankruptcy code section 361: the party must realize the “indubitable equivalent” of the value of its interest in the collateral.

Indeed, DIP financing often gets super-priority status via priming lien on assets that may have already been pledged to other creditors, as long as original creditors are adequately protected. This makes DIP lending relative safe.

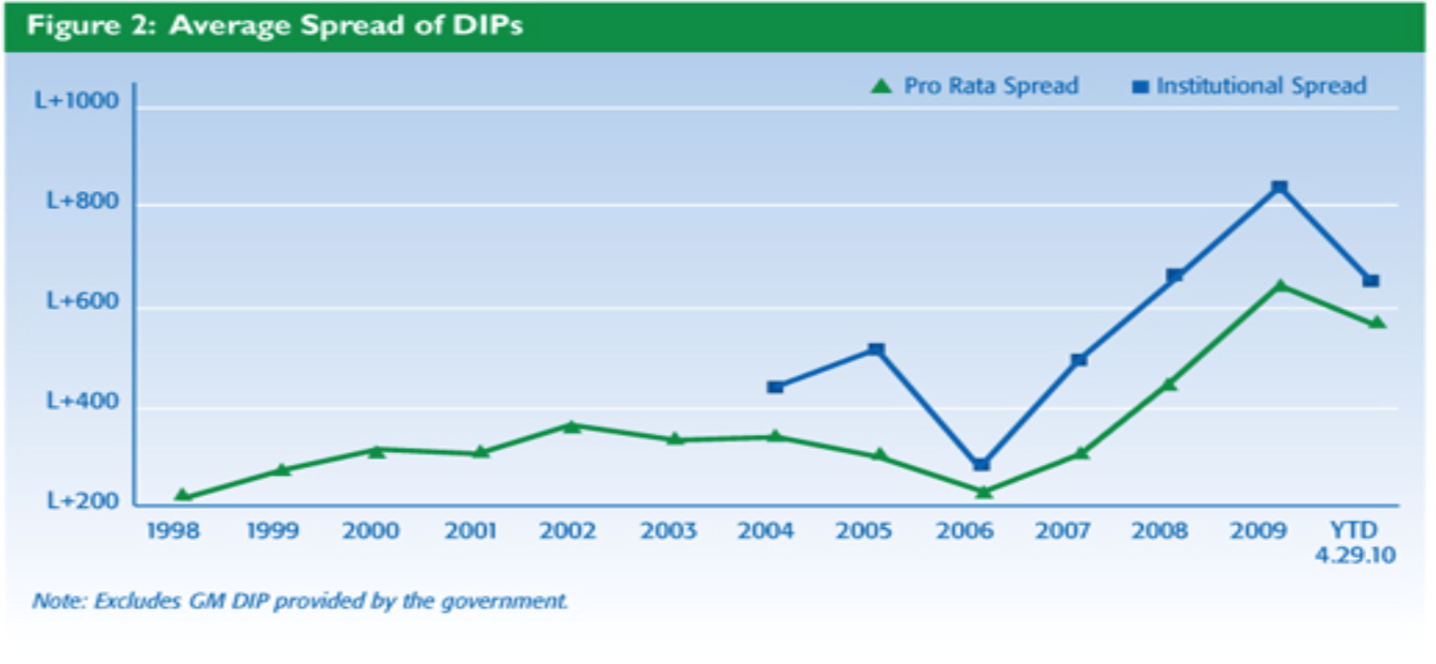

However, in 2007‐2008, unavailability of financing led to liquidation of several companies. In 2009, DIP loans commitments resurged, but they required substantial returns, as high as LIBOR plus 1000 basis point, with a 3% LIBOR floor. In addition, debtors have had to provide substantial additional inducements to DIP lenders, including the roll up of prepetition claims into the new credit facility with super-priority interests, high financing fees, short maturities, and restrictive borrowing limits.

The figure below shows how spreads on revolvers (pro rata spread) and term loans (institutional spread) peaked in 2009, and began coming down in 2010.

Source: Wall Street Prep RX guide

In the recent years, DIP financing has been a safe and lucrative business for banks and asset managers, earning them high fees and interest rates with minimal risk.

However, bankruptcy law requires DIPs to be repaid, generally fully in cash, for a company to emerge from court protection: to repay this debt firms often use the proceeds from assets sold in bankruptcy auctions or from exit loans. With financial markets in turmoil, oil prices collapsing and unemployment soaring, due to the recent coronavirus outbreak, finding asset buyers or exit lenders is now becoming increasingly difficult. Consequently, some DIP lenders have taken losses after the pandemic upended business projections, severely slashing enterprise values.

Sanchez Energy Corp., a Houston-based shale driller, was negotiating a restructuring proposal to pay off its $200 million DIP when oil prices crashed and the DIP lenders agreed to take a major equity stake in Sanchez.

Restaurant owner CraftWorks Holdings Inc. was on the path to exiting chapter 11 before the pandemic forced it to close its restaurants, eliminating revenue and putting its DIP into default.

VIP Cinema Holdings Inc., a supplier of movie-theater seats, cancelled its planned restructuring and shut down permanently. The company has said a liquidation won’t generate enough money to pay off $33 million in DIP loans.

Even if DIPs remain accessible due to its various benefits for creditors, the terms might get more onerous, squeezing recoveries for other creditors, according to lawyers and bankers. DIP financing is extremely important, since, without proper funding, companies can’t operate in bankruptcy and reorganize successfully, raising the likelihood they will end up dismantled through liquidation.

Extension of credit

Another liability-related aspect of restructuring transactions is extension of credit, when a creditor grants new credit to the debtor, usually on the condition of a new equity infusion and/or a grant of additional collateral. Financing a turnaround, the bank temporarily avoids the costs and the risks associated with a Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

This is something that can considerably change the fate of the company as confidence in the company’s viability on the longer-term increases, based on the assumption that working capital will increase. However this is not always the case, it is possible companies need to use the capital provided for short-term cash flow deficits resulting in greater loss for the bank.

In case unconditional extension of credit results in too much risk for creditors, they can choose to use conditional financing. This happens especially in cases of operational challenges or uncertain macro environments. It means the company has to accept further restrictions to its operating activities for it to be provided with an extension of credit. Examples of conditions that may be imposed are the obligation to take steps to limit the cash flow deficit, having to monetize certain parts of the bank’s collateral or seek alternative financing. In conclusion, the company would pursue its core business plan on a limited base.

In the case these additional financing scenarios are unacceptable, and a bankruptcy filing occurs, bankruptcy legal code require a cancellation of debt before re-levering the capital structure. This means creditor claims are exchanged for cash, debt or equity valued at less than the principal balance of the original debt. Under these conditions, income created by COD, namely the amount of debt forgiven, is not taxed.

0 Comments