Introduction

The German economy has navigated through a challenging landscape marked by the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, energy crises, and ongoing global economic uncertainties. Germany, historically recognized for its export-led growth, faced a contraction in GDP of 0.3% in 2023, with economic activities dampened by a loss in purchasing power, high interest rates, low consumer sentiment, high construction costs, labour shortages, and elevated energy prices. This, coupled with geopolitical risks and a cooling global economy, has prompted analysts to forecast a bleak 2024 and 2025 for the German economy, with projected growth rates of 0.6% and 1.2%, respectively.

With challenging economic conditions come bankruptcies. Germany is no different. In 2023, corporate bankruptcy filings in Germany increased 23.5% to 18 100 cases. Although this is similar to pre-pandemic levels, as the Covid-19 pandemic meant a temporary suspension of bankruptcy reporting requirements, the figure is expected to increase further in 2024. The most affected sectors were manufacturing, trade, services and real estate.

What went wrong in the real estate sector

The real estate sector has particularly suffered due to the negative factors impacting the German economy, a country in technical recession since Q2 2023. The high borrowing costs and the elevated cost of building materials are key factors for the downfall of the real estate sector.

Property prices in Germany, according to the nationwide house price index developed by the Federal Statistical Office, Destatis, were down 10.23% in Q3 2023, after declines of 9.62%, 6.8% and 3.57% in the respective three previous quarters. This marks the biggest property crisis Germany has faced in decades. While initial fears of trouble were on investors and landlords, it seems that real estate developers are the biggest losers. Some notable developers that filed for bankruptcy in 2023 are Gerch, Euroboden and Immobilien Group, on top of the three developers we will conduct case studies on in this article.

From a pure financial perspective, the crisis is clear. Faced with decreasing asset values, the highly levered property developers are finding it difficult and expensive to refinance their loans, with the cost of capital staying high. Maturities are approaching for many of these loans. On the revenue side, developers in Germany followed a simple model in the last few years: they financed real estate projects with plenty of debt, especially mezzanine, and little equity and convicted institutional investors to pay ahead of the conclusion of these projects. These investors, most notably pension funds, were happy to pay ahead for the unfinished sites, as there was a lot of competition to secure these buildings, as in any property boom. Also as with every property boom, the bubble bursts eventually, in this case leaving developers with started projects that they cannot get anyone to agree to buy ahead, nor they can refinance and finish. Investors, tempted by the high yields on bonds and other more attractive investments, are expecting high rental yield, therefore, even if willing to pay ahead, they will pay much less than before for a finished sight. Lastly, the increasing cost of building materials, due to high energy costs faced by manufacturers, does not help developers’ situation.

Banks, which are the prime lenders to property developers are, of course, in trouble, too. Germany’s Deutsche Pfandbriefbank AG, a bank with high exposure to the property sector has recently increased loan loss provisions. Landesbanks, which are major state banks in Germany, are particularly exposed. Helaba, BayernLB, LBBW and NordLB all posted provisions of about €400 million in total in the first half of 2023, a much larger figure than previous years. Swiss lender Julius Baer has had to write down huge loans for a particular troubled property developer, Signa.

Case study I: Signa

Over the last 20 years, Rene Benko, an Austrian real estate tycoon, managed to grow his company, Signa, to one of the most prominent real estate developers in Europe, with heavy exposure in Germany. That was until 29 November 2023, when Signa Holding, the holding company of the Signa Group, filed for bankruptcy in Vienna, giving management 90 days to come up with a restructuring plan.

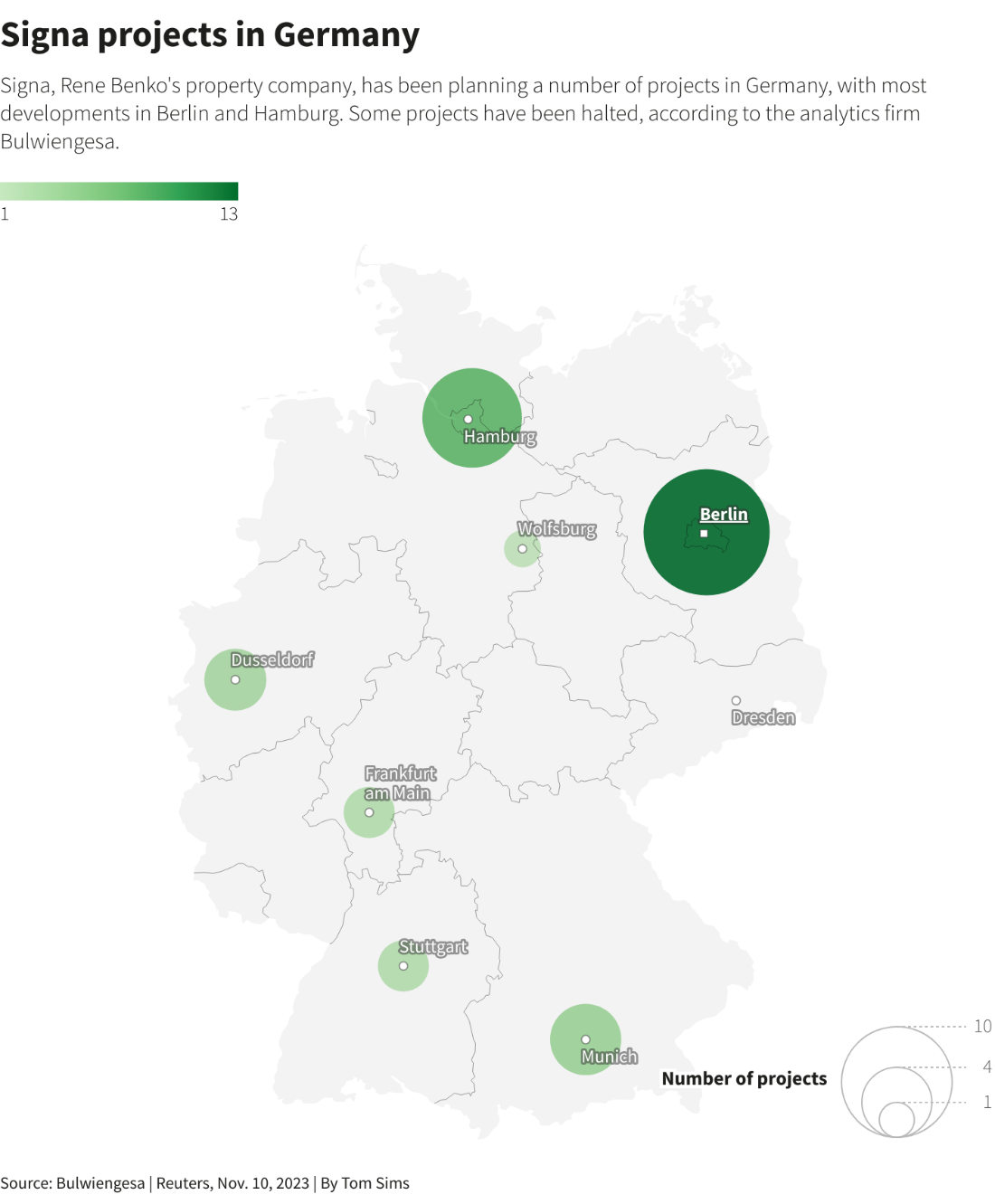

Signa’s Exposure in Germany

SOURCE: Reuters and Bulwiengesa

The Signa group had its rise fuelled by plenty of cheap debt and high-profile investors, including two of Europe’s wealthiest families, the Peugeots and the Rausings, Lindt CEO Ernst Tanner and Formula One legend Nikki Lauda. Lenders to the group included Julius Baer, Credit Suisse, Bank of China, France’s Natixis and Italy’s UniCredit. In total, 120 banks are exposed to Signa.

What could go wrong? A lot, it seems. Rene Benko was regarded as a charismatic, yet mysterious figure, that built a real estate empire with an extremely opaque structure of more than 1000 entities. Yet the business model was relatively simple. Benko relied on 2 corporate entities for most of Signa’s revenue: Signa Prime and Signa Development. With the former, Benko’s model was to buy department stores and refurbish them into more luxurious stores, which made valuations rise. This rise was at first organic, fuelled by consumer demand due to cheap money, reaching a peak in 2019. Signa Development also did well, as the plan was to build offices buildings and venues and sell them quickly, a concept which was hit by falling property prices. Signa Prime and Signa Development owned assets worth €27bn and €25bn, respectively. Most notably, Signa owned Selfridges in London, KaDeWe in Berlin, the “Golden Quarter” in Vienna, a luxury shopping area, and the Chrysler building in New York.

With the rising interest rates and the crumbling property sector in Germany, lenders and investors turned their attention to Signa. Initially, rental income for Signa Prime seemed stable compared to the falling rents across comparable buildings to the ones owned by the firm. It quickly became clear that two of Signa’s most important tenants, KaDeWe and Galeria Karstadt Kaufhof, were sustaining this high rental income, but not because the market commanded it, but because they were owned by Signa, too. Next came the failure of Signa Sports, a sports E-commerce platform owned by Signa Holdings, on October 23. This was followed by the insolvency of Signa Real Estate Management, the company responsible for day-to-day administration of property projects in Germany, in mid-November. Vital funding was pulled for both inexplicably, which made investors question what Signa did with the funds they lent.

Just before declaring bankruptcy, Signa Holding offered themselves to Elliot Investment Management, but the company refused to buy, citing concerns over Signa’s high amount of debt, its overly complex ownership structure and the role of Rene Benko, who had already been ousted from the firm at the start of November.

Immediately after the bankruptcy filing, creditors came knocking, but the 120 banks that had lent to Signa quickly realised they had little idea what their debt was secured against and what they could claim, due to the opaque structure of the firm. JP Morgan estimated that the company owed €13bn to lenders at the time of the bankruptcy filing. Since then, Signa has put half of the Chrysler Building in New York up for sale, saw its largest development project in Germany, the “Elbtower” in Hamburg, fall into bankruptcy, was hit with accusations that Benko had stolen €300m of Signa’s funds before its collapse, saw another one of its flagship buildings, the KaDeWe store, file for bankruptcy and was hit with a criminal complaint by creditors. The company was recently taken into administration by the Austrian government after failing to put together a viable restructuring plan in the 90-day period of self-administration. But that is not the worst part, as Christof Stapf, the Austrian insolvency lawyer tasked with coming up with a restructuring proposal for Signa, declared that a mere €250m of the €5.6bn owed by the company to lenders at the end of January 2024, was secured against tangible assets.

This complex restructuring story underscores the irrationality of the property bubble in Germany and in nearby countries: developers like Signa borrowed cheap money from lenders, who did not ask too many questions due to the company’s backing by high-profile investors, and thus did not secure many of their loans. With the inevitable fall of property prices, fell also Benko’s empire, and left creditors with the need to write off huge amounts of loans. A prime example is Julius Baer, which saw its profit fall 52% YoY, after having to write off its $700m exposure to Signa.

Case study II: Aggregate

In June 2021, Aggregate Holdings’, a titan of real estate investment in Germany, embarked on an ambitious plan to create 2 million square feet of space on Kurfuerstendamm, one of the most famous avenues in Berlin, with the acquisition of the Fuerst project. However, the high construction costs and debt payments, coupled with the economic climate shift, with low-interest rates giving way to a series of rate hikes by the European Central Bank, resulted in budget shortfalls and the halting of building work.

As part of its strategic response, on 27 April 2023, Aggregate initiated the formal restructuring process, by solicitation of consent for its 2024 and 2025 notes, which was successfully approved by the required majority of bondholders in the following month. This approval was crucial for the restructuring process, as it included key amendments like the removal of the Loan-to-Value covenant and the deferral of coupon with an increased rate of interest.

Subsequently, on 5 May 2023, Aggregate concluded the divestment of VIC Properties, the largest real estate developer in Portugal, in a transaction valued at over €670m. This resulted in Aggregate being released from its guaranteed obligations related to the €250 million 3% Pre-IPO Convertible Bonds issued by VIC Properties and due in 2025, which is set to free up approximately €475m for Aggregate. Aggregate’s CEO, Cevdet Caner, stated that this transaction marks another significant step in the company’s strategy to simplify its capital structure and focus on its core markets, working towards realising the value of its prime Berlin-based assets over time.

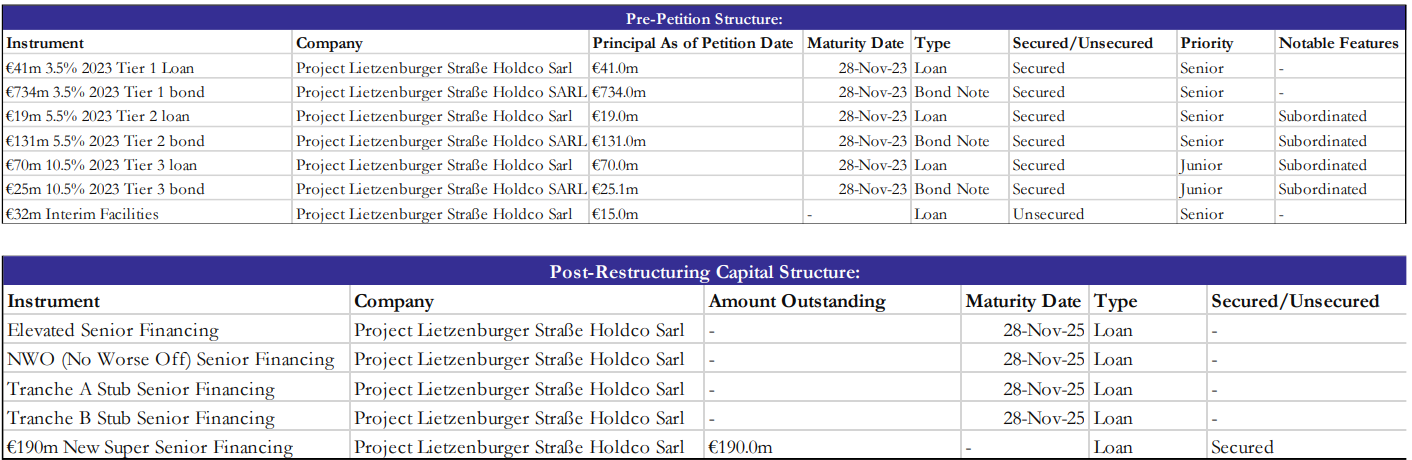

The financial strategy for navigating through these challenges involved securing a convening order from the High Court on 1 November 2023, allowing Aggregate to convene creditor meetings for voting on a restructuring plan under Part 26A of the Companies Act 2006, a provision analogous to Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the US. This plan aimed at slashing its existing €1bn-plus debt pile by around €250m and extending the maturities of its post-workout liabilities, while also raising €190m of new financing.

Source: Hossein Dabiri and Shab Mahmood, ION Analytics Community

Source: Hossein Dabiri and Shab Mahmood, ION Analytics Community

The court’s approval highlighted concerns about the short notice given to creditors and emphasized the need for a sufficient notice period, reflecting on the liquidity crisis that had been looming over the company for months. Despite these challenges, the plan moved forward, with the restructuring aimed at not only addressing the immediate financial distress but also positioning Aggregate for future stability and growth.

The restructuring plan proposed a significant shift in the company’s financial structure, including the complete write-off of Tier 2 and Junior Debt, reflecting their out-of-the-money status, and the introduction of new Super Senior Financing to support the completion of the Development.

Diverging from the narratives of companies like Signa and Consus, Aggregate represents a rare positive turnaround success in real estate development. By focusing on the German market, Aggregate is set to benefit from Europe’s stability and growth. This approach not only highlights a shift towards market specialisation but also serves as a model for financial and operational strategy across the industry.

Case study III: Consus

The restructuring story of real estate developer Consus takes its roots long before securing debt financing. Cevdet Caner, the property magnate at the center of the German real estate market, has also played a role in Consus’s struggles. While Caner denied the allegations himself, he is likely to have had played a major role in a 2020 deal that saw transfer of a stake in Consus from Aggregate Holdings to Adler Group, a firm where Caner’s brother-in-law holds a stake. Adler’s share in Consus then reached 94%, and Caner later went on to become the CEO of Aggregate in 2022. While this may not seem relevant initially, the presence of Caner in the background of Consus is important. Caner has previously presided over Germany’s second-largest real estate bankruptcy, Level One group. In 2008, the firm fell into insolvency, owing creditors more than €1bn. A decade-long criminal case was initiated after creditors alleged the money was diverted out of Level One group by Caner, although eventually he was acquitted. Despite nothing being proven, Caner’s proximity to Consus may raise some eyebrows.

Consus Real Estate is a Germany-based company with specialization in the real estate sector. Founded in 2008, its focus is on the development of entire neighborhoods and standardized flats, as well as operation of an entire development chain – including acquisition, development and planning, forwards sales, construction and letting of real estate developments – through its subsidiaries. Aggregate Holdings acquired a majority stake, 69%, in Consus in 2017, creating the largest listed real estate development company in Germany at the time. In 2020, 94% of Consus would be owned by Adler Group.

Adler would first show concerns over its subsidiary, Consus, in early 2022. The reputation of Adler and Consus was badly damaged when KPMG dropped Adler as its client in April. In its statement, KPMG said that Adler withheld around 800 000 emails and noted that the troubled Cevdet Caner has been involved in making decisions. KPMG declined to sign off on Adler’s 2021 annual report. The firm still published it, showing a net loss of €1.2bn, mostly due to a write-down of about €1bn in Consus’ property-development portfolio. Even though Chairman Stefan Kirsten ruled out insolvency in May, he said, “We are working through potential restructuring plans”. According to CoStar, Consus Real Estate reported a negative equity of €760-800m as of 30 June 2022.

It was obvious that the debt-laden developer was not looking good. Consus’ parent company, Adler, owed in excess of €6.1bn in external debts and had to restructure. It sought legal advice from White & Case on financing commitments and started restructuring negotiations with its creditors in November 2022. Adler sought a new secured debt financing of €937.5m to stabilize, citing that “the provision is subject to a positive restructuring opinion”. White & Case’s press release uncovers that the financing rationale was stabilizing operations and recapitalization, and that the law firm also advised Adler Group on amending the terms and conditions of bonds issued by Adler – spread across six series by maturity dates and interest rates – with an aggregate nominal value of €3.2bn. While Consus is not explicitly stated as the reason for restructuring, it should be noted that the developer’s position was very weak, and that restructuring was the last and only resort. In its H1 2023 report, Adler stated that in effort to restructure and improve its standing, it would continue the progress of repayment of debt, complete a corporate restructuring, including group simplification and platform streamlining, and improve corporate governance, with the group still searching for an auditor at the time. It also noted that it would appoint three additional board members.

However, the restructuring plan did not go through. English Court of Appeal overturned High Court’s decision, which led to the sanctioning of Adler restructuring plan. This, combined with negative equity of Consus Real Estate AG amounting to €2bn at the end of 2022, raises concerns for German and European economy. If Consus, and as a result its parent company, went bankrupt, the effects would be dramatic. Adler Group is one of Germany’s largest landlords, holding 26000 residential and 6000 development units, with a gross asset value of €9.5bn as of 30 June 2022. In the 3 years to 7 March 2024, Adler’s stock price has decreased 99.2%, dropping from €27 to €0.216. YoY, it decreased 79.5%, tumbling from €1.054. If the company went bankrupt, it would result in consequent job losses in construction and engineering, increased credit market stress, decreased investor confidence and financial distress for tenants. Germany’s forecast of economic growth is about 1% this year, which in combination with big real estate developer failures such as Adler/Consus would bring repercussions throughout Europe.

Lessons from recent restructurings

Even though the firms we looked at in case studies are not equivalent, the case-by-case commonalities still stand. The sheer value of assets and depth of indebtedness of Signa, Aggregate, and Consus indicate high reliance on future demand, expectations for which do not always meet reality. While prominent figures with good reputation, such as in the case of Signa, are more likely to replicate success, there have to be regulations that both limit maximum leverage and require debt to be secured against tangible assets. In addition, the case studies share another aspect, the hubris of CEOs. It seems that whenever a company grows to a large scale, it is particularly difficult for the C-suite to admit mistakes and attempt to resolve them. It is critical for creditors and governments to notice this in the early stages to avoid developments like in the cases of Consus and Signa. Perhaps to avoid this, regulators should appoint independent board members.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that there are similarities between the German real estate crisis and the Chinese property sector failures. The post-pandemic rising interest rates in Germany that led to much of the insolvencies and the real estate groups’ struggles are manifest in China’s interest rates provided by shadow banks – which charge higher rates for associated risks. In addition, the excessive leverage in German companies is parallel to China. While high leverage was not the reason for Chinese real estate companies’ failures, the policy aimed at reducing developer leverage – Three Red Lines Policy – was. It is essentially noted that these factors are very similar but were triggered by different catalysts. Lastly, the slowdown in demand for real estate in China caused a 0.1% YoY drop in China’s new home prices, while Germany’s struggling economy and highly fragmented and therefore competitive market also limited home price growth. While these three factors are not identical for the two countries, analysis of the similarities of the two could be helpful in preventing mass insolvency and restructuring cases in the future.

Since restructuring is usually a bad sign for investor confidence and economy in general, the approach to conducting real estate business should be changed. This could be manifested through laws and regulations limiting developers’ leverage, scrutiny over consolidation (such that “undercover bosses” like Cevdet Caner cannot interfere with mergers), and presence of independent board members acting as checks on corporate governance.

0 Comments