Introduction

The Fed’s buying spree and general pandemic response has recently scooped up most of the media attention around central banking operations. The world of financial markets stands in awe when Jerome Powell speaks of or hints at the Fed’s next moves. However, the Swiss National Bank likes to get by in a style that’s more characteristic of financial institutions in the country – subtle and under the radar. In this process the Swiss National Bank became what could be called the world’s largest hedge fund. One would associate this with exceptional strategy and calculated analyses, but the SNB doesn’t display much of it, begging the question whether this hedge fund like status was in fact an accidental byproduct of curbing franc appreciation and keeping the Swiss export-oriented economy flourishing and safe from deflation.

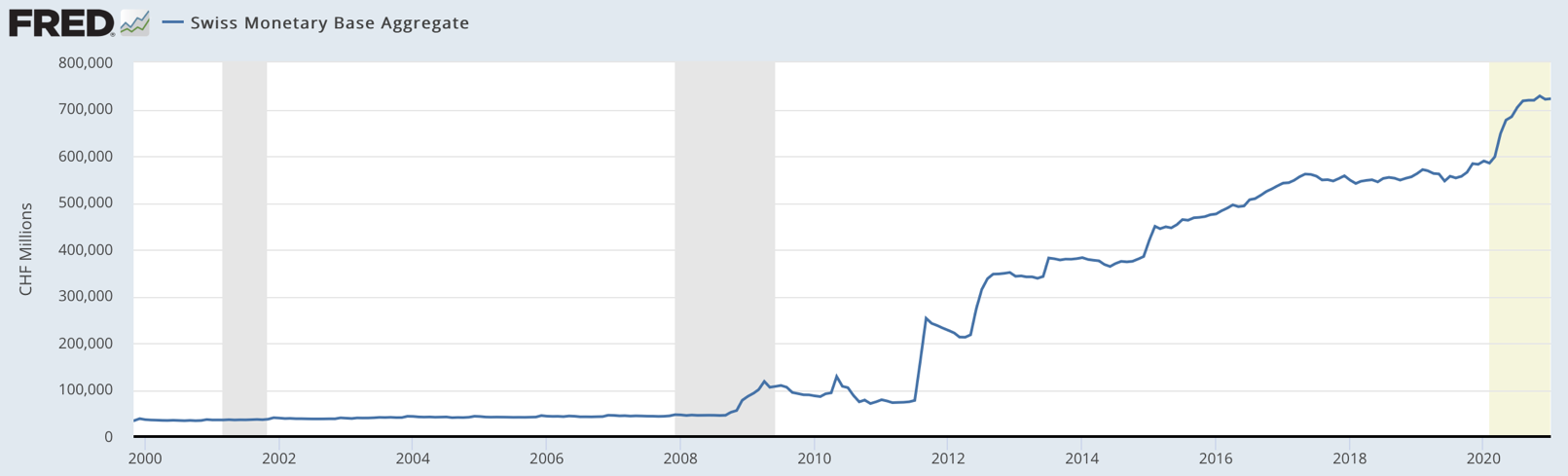

The Swiss franc has kept a status of a safe haven currency for most part of modern financial history. This creates a nearly constant stream of demand for the franc that can accelerate during periods of global economic trouble. With that said, the eurozone debt crisis has been placing constant upward pressure on the currency for most part of the last decade. In fact, demand for the franc has been so great that in 2015, the SNB announced it would no longer maintain a CHF 1.2 to EUR 1 peg. This caused one of the most dramatic swings for a developed economy currency to be ever observed – the franc instantaneously shot up in value, appreciating by 20-30% within the minutes to hours of one morning, eventually having found a rough ceiling at parity to the Euro. However, the SNB couldn’t step away to the sidelines forever, as selling of the Swiss franc had to be maintained for the currency to not appreciate beyond control. To support these operations which mostly equated to buying up other leading currencies with the franc, the monetary base of CHF has exploded from 80B to nearly 800B in the past decade (refer to Figure 1). Such monetary base expansion, although quite significant and very different from that historically observed in Switzerland (look at 2000-2009), doesn’t bring up too many red flags if the currency’s buying power isn’t greatly altered. In fact, in a post GFC world this is a phenomenon that can also be observed in many other currencies, including the US Dollar. However, the key difference arises in the following operations performed by the SNB, and more exactly the types of assets it deems itself appropriate to hold in the foreign currency it buys with its freshly minted francs.

Figure 1: Swiss Monetary Base Aggregate in CHF Millions. Source: FRED

SNB Assets: A central bank, a sovereign wealth fund, a hedge fund or all of them combined?

The SNB decidedly doesn’t limit itself to only bonds or debt instruments, as opposed to the ECB and Fed, which made this the traditional central bank asset purchasing model. In fact, the SNB barely even holds any assets denominated in its own currency with ~90% of its balance sheet in foreign currency investments. Moreover, its total asset value drifted around the trillion CHF mark in January of this year when the most recent data was released, equating it to around 150% of Switzerland’s 2019 CHF 650B GDP. Things get even more interesting when going into what types of foreign currency investments the SNB holds, with 20% being equity holdings.

What is even more surprising is that even though the SNB holds ~CHF 200B of foreign equity, it doesn’t seem to outline a very clear strategy for how it aims to manage its holdings. For comparison’s sake, its US equity holding of $140B as of EoY 2020 is bigger than the AUM of Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund. Yet the official strategy can be pointed to being as simple as concentrating on the mega and large cap stocks of popular stock market indices… The SNB does not provide a clear exit plan from its investments and oftentimes actually displays negligence in building its positions beyond what ‘proper’ risk management for a central bank would allow. While in recent years it has slowly managed to liquidate portions of its holding that were getting too large, especially in mega caps such as Apple or Microsoft, where their ownership at one point expanded into single digit percentages. If one is going with the story of the SNB being involved in foreign currency assets solely due to the need to curb the franc’s deflationary pressure, it is quite hard to stomach how a newly opened position in Q4 2020 in Nikola Corporation works towards that goal. This is just a glimpse of a long list of speculative names visible on the SNB balance sheet that heavily drift away from the official idea of buying proven large cap companies. The SNB was also lured into large investments in companies such as a Chinese loss generating EV maker Nio (~3M shares), which as of the first week of March is experiencing a nearly 50% correction from its ATH established just a couple of months ago and Zoom (~700K shares) whose business is yet to prove itself in a post-pandemic world after the company shot to center stage due to its Video Communication software. While Zoom and many other businesses which the SNB has bet on could be very lucrative investments due to forward-looking business models and improving profitability (and for many just beginning to outline how to get there), understandably some serious questions arise about whether it’s a central banks’ job to make those high-risk growth investments. If risk has already been discussed concerning the Bank of Japan being the country’s largest ETF holder, why does the post-2008 version of the SNB deem it appropriate to not only make bets on the growth of markets but also pick out and come out with its own allocations into any stock its very opaque investment philosophy sees financial gain potential.

With the current market circumstances, it is clear no one sees a need to ring too many alarm bells, as 2020 saw the SNB post more than CHF 20B of profits, and 2017 and 2019 saw earnings around the 50B mark. This, however, does not point to a lack of weakness from the SNB and massive risk exposure to a turnaround in equity prices. 2018 provided perhaps one of the first warnings, when the SNB posted CHF -15B earnings, yet failed to rethink their investment strategy or show any concern. Then came Q1 2020 with the March Covid-19 market crash decimating equity valuations across the board and sparking a near CHF 40B loss for SNB. While the positive rebound of the stock market allowed SNB to quickly gain back its losses next quarter, it is surprising to see the bank does not seem to publicly reveal whether it has learnt any lessons. If the equity environment that this golden decade for the sector has gotten us used to ends, how is the SNB planning to go about liquidating its positions that could flood or scare the market into panic. The ultra-low interest rate environment isn’t planned to be a regular fixture in the US market, and once those yields pick up SNB might face real trouble trying to liquidate their numerous speculative growth bets that it so far seems to only be doubling down on.

Will a lesson only be learnt when it’s too late?

These are all very real questions and concerns for a bank that is famously considered the epitome of a financial safe haven, as the last decade has turned it into one of the most risk-hungry central banks of the developed world.

What happens when a central bank tangles itself into nearly $17K worth of US equities for each member of its population with no real way to unwind itself from the position when a sudden need arises?

Understandably, these are not questions that many parts of the government will attempt to get the SNB to answer. Why? At the beginning of 2020, a new law doubled the amount of profits the SNB could share with the federal government and the cantons of the country from CHF 2B to 4B, with the split lying at a 1:2 ratio respectively.

That still makes one wonder, with the dividend of the SNB’s stock maxed out to the legal maximum of CHF 15 (0.29%) and a P/E ratio of 0.042, the SNB is clearly not treated as an institution that was supposed to post these humongous by any measure profits. Neither is there confidence in it being able to continue to do so. Hence, when will we see the SNB set out a real plan for how to untangle itself from a position it should have never been found in.

Or does the SNB need to step up to its hedge fund like status and start acting like one in a transparent manner, while possibly separating into 2 different arms to provide clarity and reassurance around its operations?

0 Comments