Introduction

On July 17th 2020, in the midst of severe market volatility, Bill Ackman, the famed activist investor, raised the largest SPAC in history. With an IPO of $4bn, Pershing Square Tontine Holdings is just one of the many large SPAC fundraisings that have been conducted this year. With many investors clamoring for the use of SPACs over the traditional IPO process, we at BSIC think it is imperative to understand what SPACs are and how they work.

A SPAC, Special Purpose Acquisition Company, has a very simple business model: create a shell company, raise money in an IPO, and use the funds raised to merge with another company. As the company that the SPAC merges with becomes publicly traded, SPACs have inevitably become an alternative to the traditional IPO process.

Source: Seeking Alpha

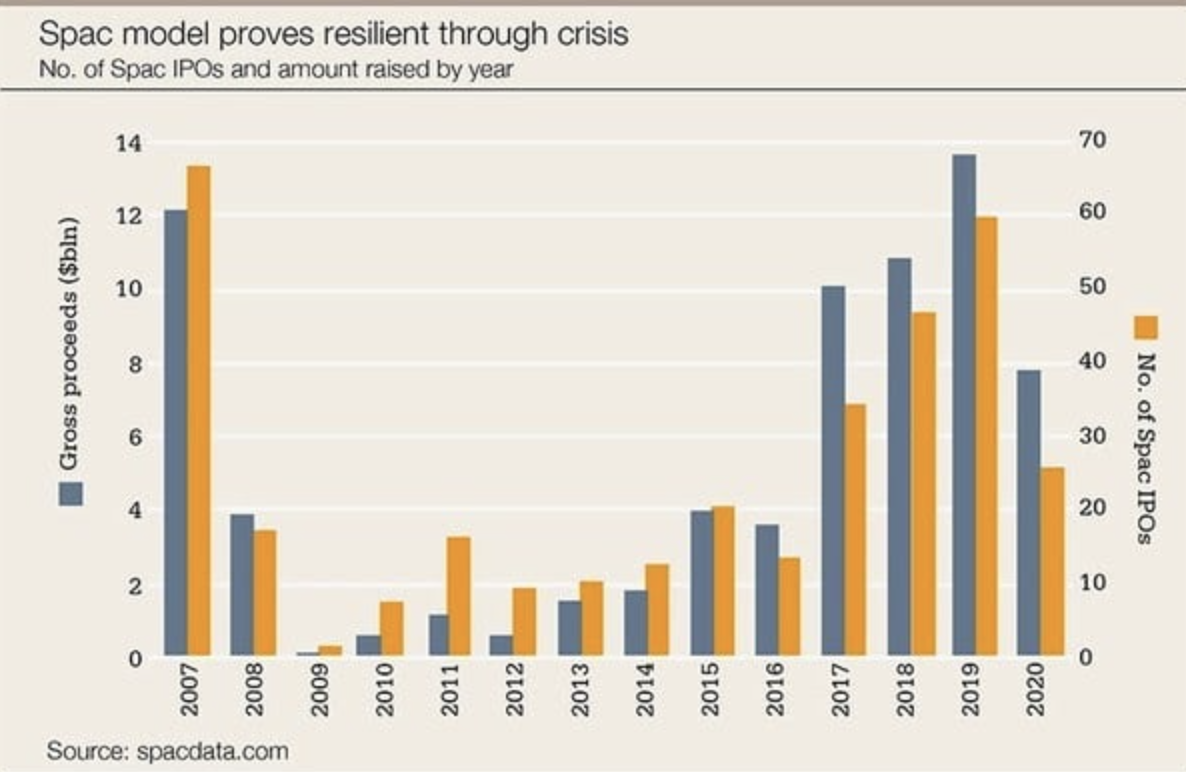

Born in the 90s, SPACs were perceived as abusive to investors and were associated with penny-stock fraud schemes. However, the introduction of shareholder protections as well as the entrance of reputable firms in the market has allowed for a rebranding of the space. Firms like Goldman Sachs, TPG and, more recently, Pershing Square have raised SPACs that have attracted significant investor demand. In addition, with companies like DraftKings and Virgin Galactic going public through SPAC transactions, the legitimacy of SPACs has improved drastically. Not surprisingly, a more solid reputation resulted in a resurgence in SPAC activity in 2017, when 55 SPACs were created, when compared to just around 15 in 2016. This positive trend has continued since then and is expected to further strengthen due to the Covid-19 pandemic. With companies seeking more certainty in their fundraising process and sponsors looking for discounted valuations, it is likely that we will continue to see further developments in the space.

Structure of SPACs

SPACs are created by “sponsors”, who are usually private equity funds or other investors that are well acquainted with the M&A process. Upon the creation of a SPAC, sponsors will retain an investment bank to conduct an IPO. As the SPAC is essentially a shell company with no real operations, the process requires significantly lesser time and documentation than the IPO of a traditional company. The SPAC then raises funds on public markets by selling “units”. Each unit of a SPAC is made up of 1 share, usually priced at $10, and warrant or a fraction of a warrant. This warrant, usually exercisable at a price of $11.5 after the de-SPAC transaction, is given to investors for free and is meant to compensate investors for the additional risk that they take on by investing in a blind-pool of capital. The sponsor, on the other hand, gets special “Founder Shares”, which are usually purchased for a total price of $25,000. Upon the completion of a merger, these Founder Shares are converted into 20% of the share capital of a SPAC. This 20% equity stake given to sponsors as a success fee is known as the “Sponsor Promote”.

The money raised from the IPO is then transferred to a trust account, which then invests the funds in short-term U.S. treasuries/money market funds. Interest on these funds accumulates in the trust account, with a portion being used to cover the working capital requirements of the sponsor. After the IPO, the sponsor has to find a company to acquire by a certain deadline. This deadline is often capped at 2 years, but can sometimes be extended to up to 3 years. The choice of the target is subject to certain constraints: the target cannot be valued at less than 80% of money raised by the SPAC and needs to belong to the same industry that was outlined at creation by the sponsor. As for any upwards limit on the target size, there is none. On the contrary, firms 4x – 6x as large as the SPAC are usually chosen as targets as a way to reduce the dilutive impact of sponsors’ shares and warrants. The additional capital for these large acquisitions is derived from PIPE investments: Private Investment in Public Equity. This is when the sponsor raises additional money from other PE funds or hedge funds to finance the acquisition.

Once a target is found, it is announced to the public and the SPAC’s investors can vote on whether or not they approve of the transaction. In addition, if some investors do not wish to own the merged company, they can choose to redeem their shares and get a pro rata distribution of the funds in the trust account. This usually means the initial $10 investment + interest. As the approval of investors and a low redemption rate is crucial for the success of the merger, many sponsors engage in a roadshow to market the transaction to investors. Keep in mind that the roadshow for a SPAC is much shorter than that of a traditional IPO: with a SPAC you already have an investor base that has bought in, you just need to convince them not to sell.

If shareholders approve the transaction and there are not too many redemptions, the SPAC merges with the target company, successfully taking it public. However, if the transaction is not approved, the SPAC has to go back to sourcing new deals and conducting due-diligence. Eventually, if an acquisition target is not found, the SPAC is liquidated and all investors receive a pro rate distribution of the funds in the trust account.

Advantages for Target Company

The greatest advantage for target companies that merge with a SPAC is the certainty of pricing. For a traditional listing, a company has to publicly announce that it wants to conduct an IPO, spend 5-6 months finalizing a prospectus, and then go on a roadshow to market the company to investors. It is only after this long process that investors put in their orders and the shares of the company are finally priced. This exposes the company to significant risk, as it is only on the last day of this time intensive and costly process that the company has any visbility into whether there is demand for its offering, what price it will get, and how much money it will raise. This uncertainty is amplified when there is greater volatility in the market, with companies often scrapping IPOs mid-way through the IPO process if market conditions deteriorate. This makes SPACs very attractive for companies desiring to go public, especially with the coronavirus causing significant market volatility. When dealing with a SPAC, not only does the target company have visibility on pricing from the very start, it is able to play an active role in negotiating the price and size of it its offering. In addition, even if a SPAC demands a discount on the intrinsic value of the company’s shares due to volatility in the overall market, at least the target company can be certain of how large the discount is. That certainty is not possible with an IPO.

In addition, a SPAC is a much faster way to access public capital markets than an IPO. Due to the large number of filings and disclosures associated with a traditional IPO, companies usually take around 6-7 months to complete the entire process of going public. However, as the IPO for a SPAC has already been completed, the administrative burden of merging with a SPAC to go public is far lower. This allows many companies to merge with a SPAC and go public within a span of 2-3 months.

A more hotly debated advantage that SPACs perceive to have is better pricing. Pre-IPO investors of companies have complained for years about the underpricing of IPOs and the “IPO Pop” phenomenon. It is easy to understand where this dissent comes from if the IPO process is explored in depth. Firstly, it should be noted that investment banks do not use a market-based approach to set prices for IPO. Instead they use an IPO roadshow where they introduce the company to a number investor groups and receive orders from these investors. Banks tell every IPO Prospect that they have two main goals: 97% of the investors they meet need to submit an order for the IPO, and the IPO needs to be 30x oversubscribed. This is where the problem lies: In what other market do you price an asset so low that you have more than 30x the demand needed to clear the market? In addition, this does not even take into consideration the impact of retail investors, who are not invited to participate in the IPO process. This means that the true oversupply is often much more than 30x. A large factor possibly driving this underpricing is the the major conflict of interest banks have between the IPO company and its institutional clients, with whom they engage in more frequent transactions. Banks have a strong incentive to underprice IPOs, get orders from an extremely large investor base, and only make allocations to their most lucrative clients in exchange for greater commissions in the future. This relationship has been explored in a study published by the American Journal of Finance, which found a clear correlation between the broking revenues from a client and the allocations they receive in IPOs.

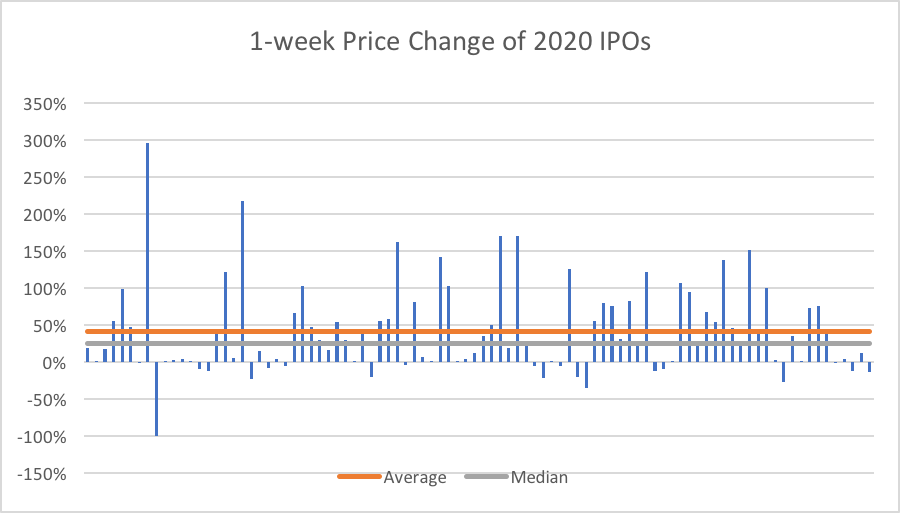

Source: BSIC

To better understand if SPACs actually offer better pricing, we measured the IPO pop for both conventional IPOs and for SPACs by analyzing the 1-week price change after the IPO/de-SPAC transaction. As seen by the graph above, companies that IPOed in 2020 consistently saw positive 1-week changes in their prices, with an average 1-week price increase of 41% and a median price change of 25%. In addition, more than a third of the companies saw an increase greater than 50%.

Source: BSIC

SPACs, on the other hand, were more of a mixed bag. The 23 SPACs that conducted a de-SPAC transaction in 2020 had an average price change of 24% and a median price change of -4.3 % one week after the transaction. 13 of these 23 SPACs saw a negative change in price, and of the 10 SPACs that saw positive price changes, only 5 saw price increases higher than 20%. However, for these 5 SPACs, the average price change was an increase of 169%, showing that the large under-pricings are still possible with SPACs.

Overall, considering their lower average and median price changes, it can be inferred that generally SPACs had smaller IPO pops than traditional IPOs. Nevertheless, due to the small sample size and the constant new developments in the SPAC space, it is hard to draw conclusions with full certainty.

Disadvantages for Target Company

One of the greatest disadvantages of going public through a SPAC is the possibility of the deal not going through if too many investors vote against the merger and/or redeem their shares. In the past, around 10% of mergers by SPACs have failed for this reason. This is a significant problem as the main reason why many companies would consider a SPAC to go public is the increased certainty of a successful listing. However, more recently, we have seen the rate of failed mergers decrease significantly. In addition, as more legitimate investors with strong track records enter the market as sponsors, and as more SPACs include incentives for investors to not redeem their shares (i.e. increased warrant coverage for shareholders that don’t redeem), it is likely that the rate of failed mergers will fall even further.

Another disadvantage of going public through a SPAC is the dilution caused to existing shareholders of the target company by SPAC warrants and the sponsor promote. As previously mentioned, most SPACs compensate sponsors by giving them 20% of the entire share capital of a SPAC upon the completion of the de-SPAC transaction. In addition, investors in a SPAC are given warrants in addition to common shares during the IPO of a SPAC. These investors can exercise these warrants after the merger and create more shares, further diluting the existing investors of the firm. However, a recent trend observed in the SPAC market is the reduction in warrant coverage ratios. This is because more established investors and PE funds are entering the SPAC market and are able to leverage their deal-making experience to offer less warrants. The SPACs with these lower warrant coverage ratios are much more attractive partners to merge with for target companies. Moreover, based on recent deals that have been completed in the market, it has been observed that many sponsors are willing to negotiate the size of their sponsor promote. Some sponsors have also agreed to a vesting schedule for their promote based on the performance of the share price. Lastly, it should also be considered that the true value of dilution for the merger target is often exaggerated. This is because SPACs often merge with companies that are 3x – 4x larger than the SPAC itself. To do so they use PIPE investments, often from other hedge funds or private equity funds. These PIPE investments do not get warrants, nor a sponsor promote. Thus, if analyzed proportionally with the entire merger, the dilutive effect of the SPAC is not too high.

In addition, another disadvantage of using a SPAC instead of an IPO is the loss of control. In a conventional IPO, the new shareholders of the company tend to be more fragmented and a large proportion of the firm’s investors are long-only institutional investors. This allows the pre-IPO owners/management to have more autonomy over the strategic direction of the company. With a SPAC transaction, on the other hand, a very large proportion of the company shares are held by the SPAC. As the manager of the SPAC, this inevitably gives the sponsor more influence over the company, reducing the autonomy of management. In addition, as many sponsors often take an active role in engaging with management and the board of the merged company, some may claim that merging with a SPAC is akin to having a permanent activist investor on the board.

Advantages for Shareholders

Perhaps the greatest benefit for investors in SPACs is the significant downside protection. Before a SPAC can merge with a target company, investors in the SPAC have to vote to approve the merger. This makes SPACs very interesting because not only do they allow retail investors to participate in an IPO, SPACs also gives them significant influence in the process. In addition, even if the merger is approved, if an investor does not like the target company, it can choose to redeem its shares and receive a pro-rata share of the cash in the trust account. This includes interest earned on the cash in the period before redemption. Shares are also redeemed if the SPAC is unable to find an acquisition target in the allocated time.

Another key benefit of investing in SPACs is the warrants given to investors. As previously mentioned, SPACs provide anywhere from one full warrant to a fraction of a warrant to investors in order to compensate them for the risk of investing in such a risky asset class. These warrants are separately traded from the SPAC’s shares and usually give investors the ability to buy additional shares after the merger at a strike price of $11.5 (a 15% premium from the IPO price). If the SPAC merges with a quality company and the share price significantly increases, these warrants can greatly boost shareholder returns. However, it should be noted that if the SPAC fails to find an acquisition target and is liquidated, the warrants given to investors lose all their value.

In addition, investors in SPACs benefit from greater transparency. In a usual IPO, due to regulatory requirements, companies are not able to give forward-looking guidance on their financials. SPACs, on the other hand, can provide such information of its prospective target as the IPO has already occurred. Thus, a target company can disclose its future guidance on metrics like revenue and EBITDA. This is a great advantage for investors as it allows them to make informed decisions when deciding whether to approve the merger or redeem their shares.

Lastly, a key advantage of investing in a SPAC is the expertise of the sponsor. As previously mentioned, target companies can lose significant control when merging with a SPAC as the SPAC controls a large proportion of the equity in the company. This greatly benefits SPAC investors as sponsors are given much greater influence on the strategic direction of a company and can use their operating experience to drive value for the company.

Disadvantages for Shareholders

One of the greatest risks of investing in SPACs is the historically dismal returns of the asset class. According to Renaissance Capital, 223 SPAC IPOs have been completed from Jan 2015 to July 2020, with 89 SPACs completing a de-SPAC transaction in the same period. For those 89 SPACs, the median return is -36.1% and the average return is -18.8%. Only 26 SPACs from that group, about 30%, had positive returns. However, many proponents of SPACs claim that the asset class has gone through a transformation in recent years, with many renowned investors entering the market as sponsors. At first glance, the data seems to support this argument of a “transformation”: the 21 SPACs that conducted a de-SPAC transaction between Jan and July 2020 returned an average of 13.1% from their IPO price. Nonetheless, if you do not consider the two highest performers from that group (DraftKings and Nikola), the average return for the rest of the peer group was -10.5%. For reference, the IPO market in the same period returned to 6.5%. Thus, from a purely historical perspective, SPACs have generally been under-performers when compared to the general market.

Another disadvantage for SPAC investors is the large promotion fees given to the SPAC sponsors. As previously mentioned, most SPACs compensate sponsors by giving them 20% of the entire share capital of a SPAC upon the completion of the de-SPAC transaction. This significantly dilutes common shareholders and has a very negative impact on their returns. In addition, the sponsor promotes also creates an agency problem between the sponsor and the SPAC’s shareholders. This is because a sponsor does not have an incentive to merge with a good quality business. The sponsor gets a 20% stake in the SPAC for free, meaning that the target company could lose 90% of its market value after the de-SPAC transaction and the sponsor would still make a positive return. Moreover, even if the business that the sponsor is targeting is a market leader, there is nothing stopping the sponsor from overpaying. After all, the sponsor is using investors’ money and makes a profit either way. This agency problem is further magnified if a SPAC is under time pressure and needs to complete a deal in short notice.

However, it should be noted that recently we have seen many sponsors choosing to reduce this 20% promote or even forego it completely to better align their incentives with investors. A great example would be Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square Tontine Holdings. The SPAC recently raised $4bn, and Pershing Square has committed to invest at least another $1bn of its own capital to purchase common shares. In addition, Pershing Square has also foregone the 20% sponsor promote and is instead choosing to purchase warrants to acquire 6.21% of the SPAC at a premium of 20%. What this means is, firstly, by rejecting the sponsor promote and pooling its own money along with those of common shareholders, Pershing Square’s interests are much better aligned with the other investors of the SPAC. In addition, the warrants that Pershing Square purchased for $67.8m are only exercisable if the SPAC’s investors earn a minimum 20% return three years after an acquisition. Failure to do produce such results will render these warrants worthless, which further incentivizes Pershing Square to seek a quality merger target. It is likely that with more competition in the market, more SPACs will follow Pershing’s example and will either reduce the size of their sponsor promote or forego it completely in return for more performance-focused warrants.

0 Comments