Introduction

European innovation has finally gotten to American shores. Over recent years, synthetic risk transfers (SRTs) have become an increasingly relevant tool within banking, prompting both industry excitement and regulatory concern. In a nutshell, SRTs are financial transactions that banks use to transfer the credit risk of certain assets (e.g. loans) to third-party investors, while the assets themselves remain on the bank’s balance sheet. These transactions enable banks to preserve their relationships with borrowers while providing capital relief and diversifying credit risk.

Banks have portfolios of loans that span a range of debt types and carry different levels of credit risk. To protect themselves, banks are required by regulators to hold regulatory capital against these loans, defined as the minimum amount of capital that banks must hold to absorb potential losses and ensure solvency during times of economic downturn. Since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the amount of regulatory capital that banks must hold has increased, limiting their ability to issue new loans and grow . Banks, therefore, looked to SRTs as a way to navigate these constraints and free up capital tied to high-risk assets without offloading them from balance sheets.

Historically, SRTs have been mostly popular in Europe, where banks faced stricter capital requirements under the Basel II, III, and IV regulatory frameworks compared to the United States. In this highly regulated environment, banks have used SRTs to efficiently manage their risk-weighted assets (RWAs), assets adjusted based on their level of risk. For example, a loan secured by letter of credit is considered riskier than a mortgage loan secured by collateral – the former requires more regulatory capital to be held against it. European banks have been able to maintain strong lending activities despite these regulatory pressures by using SRTs to reduce the capital burden associated with high-RWAs (Risk-Weighted Assets).

In today’s financial landscape, the supply and demand for SRTs has increased for several reasons. Firstly, more stringent regulatory requirements, such as the Basel IV standards, are further raising the capital that banks must hold against certain high-risk assets. Banks seeking to maximise their lending capabilities have turned to SRTs to comply with these tighter regulations.

Secondly, institutional investors, such as hedge funds and insurance companies, have increased their demand for SRTs due to a number of factors. A particular advantage is that SRTs offer steady cashflows with periodic payments at a spread over a floating rate. Moreover, large investors are able to negotiate the characteristics of the underlying asset pools. Broadly speaking, SRTs offer institutional investors diversification, income, and exposure to banks’ more tightly held assets. Thirdly, with increased market volatility and economic uncertainty, banks and investors have increasingly turned to risk-sharing mechanisms.

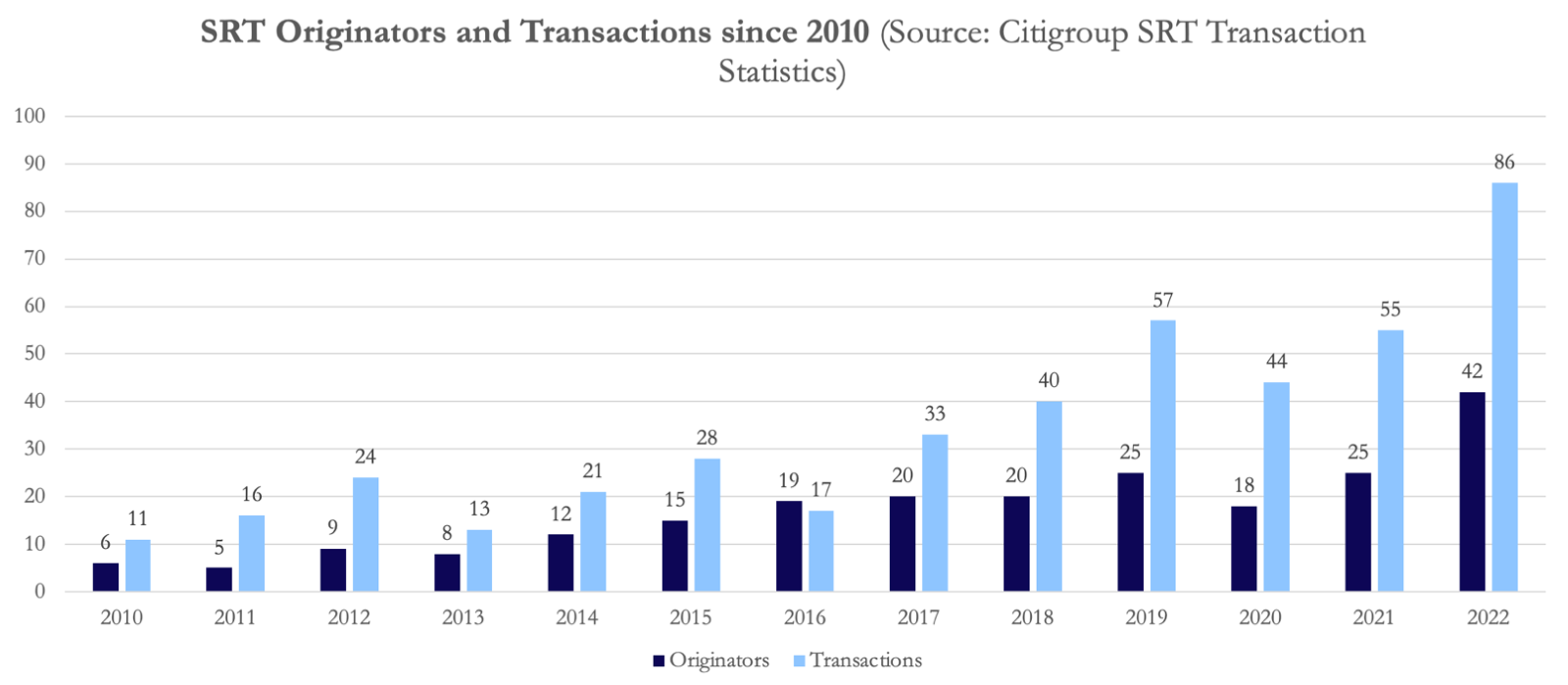

According to Pemberton, a leading European private debt manager, the SRT market has experienced an 18% annual growth rate of issuance. Currently, more than 60 banking groups now have active SRT issuance programmes and, in 2022, over 100 transactions were completed with a total issuance volume in excess of $20bn. The asset manager projects that, by 2030, at least a further 50 banks will begin their own SRT issuance programmes.

Banks profit from SRTs thanks to the capital relief, and this freed-up capital can be used to fund additional lending at higher interest rates, thereby increasing their revenue potential. By taking on more interest-bearing assets, banks can boost their net interest margin (NIM). Banks also earn fees and ongoing payments from the structuring of SRTs.

More bidders, riskier products

Due to Basel Endgame, which we will dive into as well, about 2,800 banks with less than $100 billion of assets may do deals to reduce their risks on $200 billion of loans over the next few years. There is going to be an huge expected influx of bidders for SRTs, as we have already begun to see, and even withe the influx of supply of SRTs offered from banks supply is not expected However, more bidders means tighter spreads and already investors are paying up to 200 basis points less than what they did 6 months or a year ago relative to benchmarks. In August, Morgan Stanley offered an SRT tied to a more than $4bn portfolio of loans to private-market funds. It priced less than 4 percentage points over the benchmark, people with knowledge of the matter said, contrasting with similar financings that were much wider just months earlier.

What we also have been seeing with excess demand is “Blind Pools” of SRT deals, where some banks are selling SRTs for other types of loans so broadly that they may no longer know the end buyer, something unthinkable years ago. This leads way to allowing Banks to try and tuck or hide bad loans into deals catching out many new SRT investors out, but this in and of itself has evolved into a trade. D.E. Shaw is using its data and algorithmic capabilities to analyze the less-transparent bundles of loans, using data science, it cross-references the details in the blind pools with swaths of publicly available data to help identify the borrowers, assess risk and better price the deals.

How SRTs Work: A High-Level Overview

In an SRT, the bank firstly selects a portfolio of assets, typically loans with a high cost of regulatory capital. This pool of loans could include corporate loans, mortgage loans, SME loans, and even consumer loans. After doing so, the bank structures a synthetic security which contains multiple tranches, each representing different levels of credit risk. The lowest-risk tranche might be retained by the bank, while higher-risk tranches are passed on to investors.

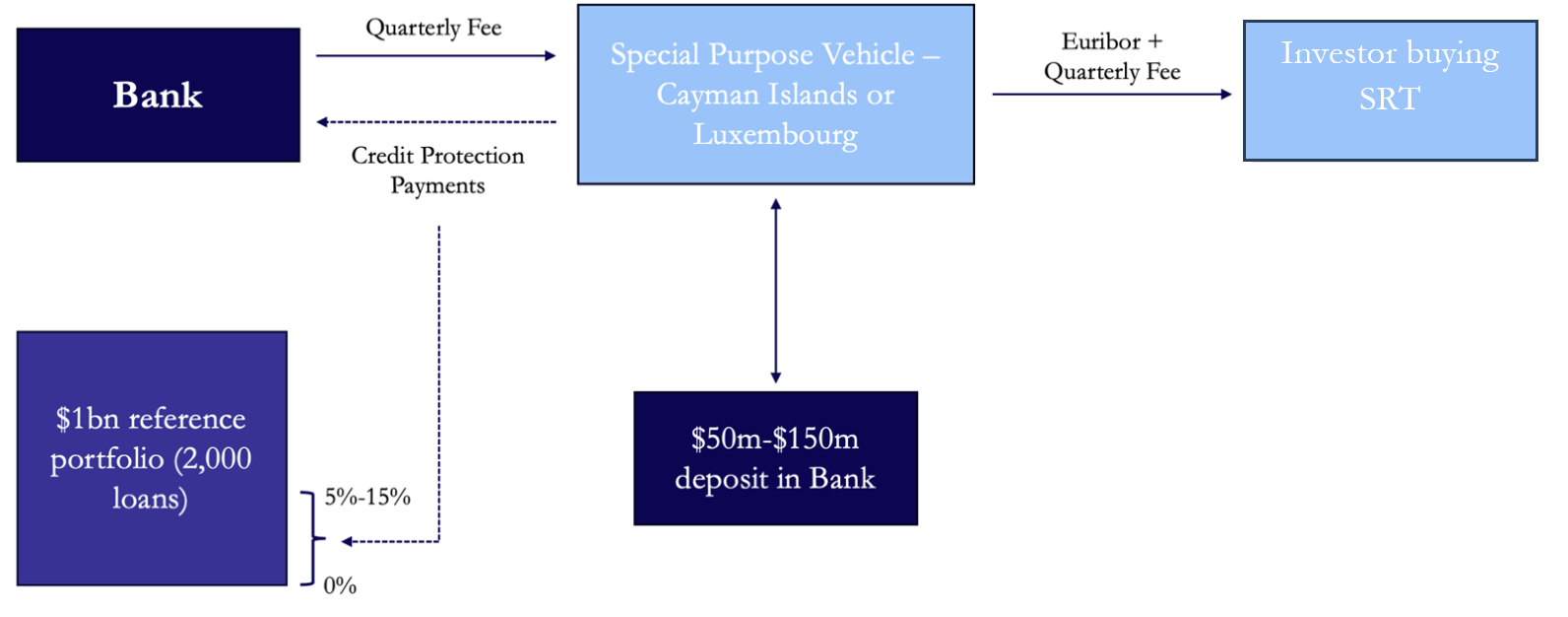

The bank then engages in a credit derivative contract, such as a credit default swap (CDS), with investors. In such a contract, the bank buys up credit-default protection on the first 5%-15% of the losses of the loan portfolio from investors, with investors receiving periodic payments from the bank in return for taking on that credit risk. Thanks to the transfer in credit risk, the bank no longer needs to hold as much regulatory capital against this portfolio. Through the SRT, the bank has freed up capital for other investments or lending.

This diagram illustrates an SRT structure where a bank selects a $1 billion reference portfolio of loans and seeks protection for 5%-15% of potential losses. The bank transfers credit risk to a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), which deposits $50-$150 million into the bank and issues the SRT to investors. Investors receive Euribor plus fees for taking on the risk, while the bank pays periodic credit protection payments to the SPV.

Regulation

Before delving into the evolution of banking regulatory frameworks that has driven the growth in popularity of synthetic risk transfers, it is important to understand the conceptual foundations for regulatory capital and its designated purpose.

At the highest level, banks and other financial institutions face expected losses (EL) and unexpected losses (UL). ELs are perceived as the cost of doing business and are anticipated based on historical patterns. Banks price for ELs through lending and account for them through loan-loss provisioning (expenses set aside as allowances for uncollected loans and loan payments). Financial regulators don’t require banks to hold regulatory capital against expected losses – what primarily concerns them are unexpected losses, deviations from expectations that can severely strain a bank’s solvency. As defined by regulators, regulatory capital is designed to absorb ULs.

Financial regulators transcribe this into capital requirements by looking at two general frameworks: leverage capital requirements and risk-based capital requirements. Leverage capital requirements assign the same requirements across different asset classes. For example, the same $100 of exposure across different asset classes, be it treasury securities, cash on balance sheet, or mortgage loans, attracts the same number of regulatory capital. Risk-based capital requirements assign different capital requirements to different exposures based on perceived risk they pose to the bank, by assigning different risk weights to each asset class. So, unlike the leverage capital framework, cash on balance sheet attracts fewer capital requirements than a mortgage loan, or a corporate loan under the risk-based capital framework.

Since SRTs transfer a portion of the credit risk (typically unexpected levels of loss) of a pool of assets to third-party investors, the bank can demonstrate that they have a lower level of unexpected loss and can hold less regulatory capital. This backdrop sets the stage for a deeper examination of SRTs and the evolution of their regulatory treatment under the Basel Accords.

The Basel Accords, established by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), have progressively refined the regulatory framework for capital adequacy, profoundly influencing the use of SRTs. Under Basel I, the regulatory landscape introduced the concept of risk-weighted assets and implemented a minimum capital adequacy ratio (CAR) of 8%. The framework was designed to encourage banks to increase their capital positions and to make regulatory capital more sensitive to banks’ perceived credit risks.

Introduced in 2004, Basel II marked a turning point with its three-pillar structure emphasising minimum capital requirements, supervisory oversight, and market discipline. For the first time, banks were allowed to use internal models to calculate credit risk which encouraged risk management strategies like SRTs. The GFC revealed vulnerabilities in Basel II, leading to the development of Basel III. Finalised in 2017, Basel III increased the quality and quantity of regulatory capital, particularly Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1), the highest tier of regulatory capital. The framework introduced the leverage ratio, the ratio between a bank’s Tier 1 capital and an exposure measure, and set the minimum leverage ratio at 3%. Moreover, banks faced stricter requirements for capital buffers to absorb unexpected losses.

Today, Basel IV builds on these earlier frameworks to increase banks’ risk sensitivity and on how to quantify them by requiring a more detailed calculation of banks’ RWAs. Under Basel IV, SRTs must meet clear and detailed criteria to achieve regulatory capital relief. While the leverage ratio remains a critical measure, the increased emphasis on RWAs makes SRTs even more relevant for banks seeking to meet these stringent requirements without diluting equity.

The evolution of the regulatory framework under the Basel Accords can shed a light on why the SRT market seems to be much larger and more mature in Europe than in the US. Synthetic risk transfers were embedded in Europe pre-GFC as European banks had already adopted the Basel II framework, which contained more risk-based capital requirements. On the other hand, US banks were delayed in transitioning from Basel I to Basel II and, in fact, leapfrogged from Basel I to Basel III in 2013.

Furthermore, pre-Basel III and pre-GFC, US regulators already subjected banks to leverage capital requirements unlike their global peers. Under a leverage capital regime, banks are unable to benefit from SRTs and transferring credit risk to third parties as all credit risks are treated equally in terms of regulatory capital. Historically, in the United States, there was just less of a focus on risk-based capital requirements which resulted in less of a focus on synthetic risk transfers.

According to Michael Shemi, a structured capital leader at Guy Carpenter, another reason for the higher popularity of these transactions in Europe is that, following the GFC in the United States, synthetic risk transfers were a solution in search of a problem. Coming out of the GFC, US banks were forced by regulators to raise large amounts of capital in order to shore up their balance sheets; furthermore, they were increasingly subject to regulatory stress tests. As a result, they were perceived to be better capitalised with stronger balance sheets than their European peers. This reflected in their valuations, as most US banks traded at a premium to their book value, enabling them to easily raise capital at these attractive valuations.

On the other hand, European banks did not recapitalise to the levels of US banks following the GFC and became risk-based capital constrained. As a result, most banks traded at a discount to book value, making it harder to raise capital by issuing new equity. Hence, this drove European banks to look for alternative risk-management tools and SRTs were the perfect solution.

There’s currently far more investor demand than supply, caused in part by a series of hiccups in the long-anticipated expansion of the US market. Investor interest revved up in the US a half-decade ago, when JPMorgan designed a new breed of mortgage-linked risk transfer. The concept turned heads in the industry, but for years it struggled to win US regulatory approval for capital relief. Then last year, as regulators took up Basel endgame, the Fed published an innocuous-looking FAQ, outlining what sort of SRT structures could qualify and what benefits they would yield.

Structure – Fully Funded Notes

In an SRT, the bank firstly selects a portfolio of assets, typically loans, that it wants to protect from potential defaults. This pool of loans could include corporate loans, mortgage loans, SME loans, and even consumer loans.

Here we will go over one of the simplest examples of the capital structure and the mechanics behind one of the SRT transactions, looking at a very granular asset class like auto loans and the most used type of SRT: A fully funded note transaction.

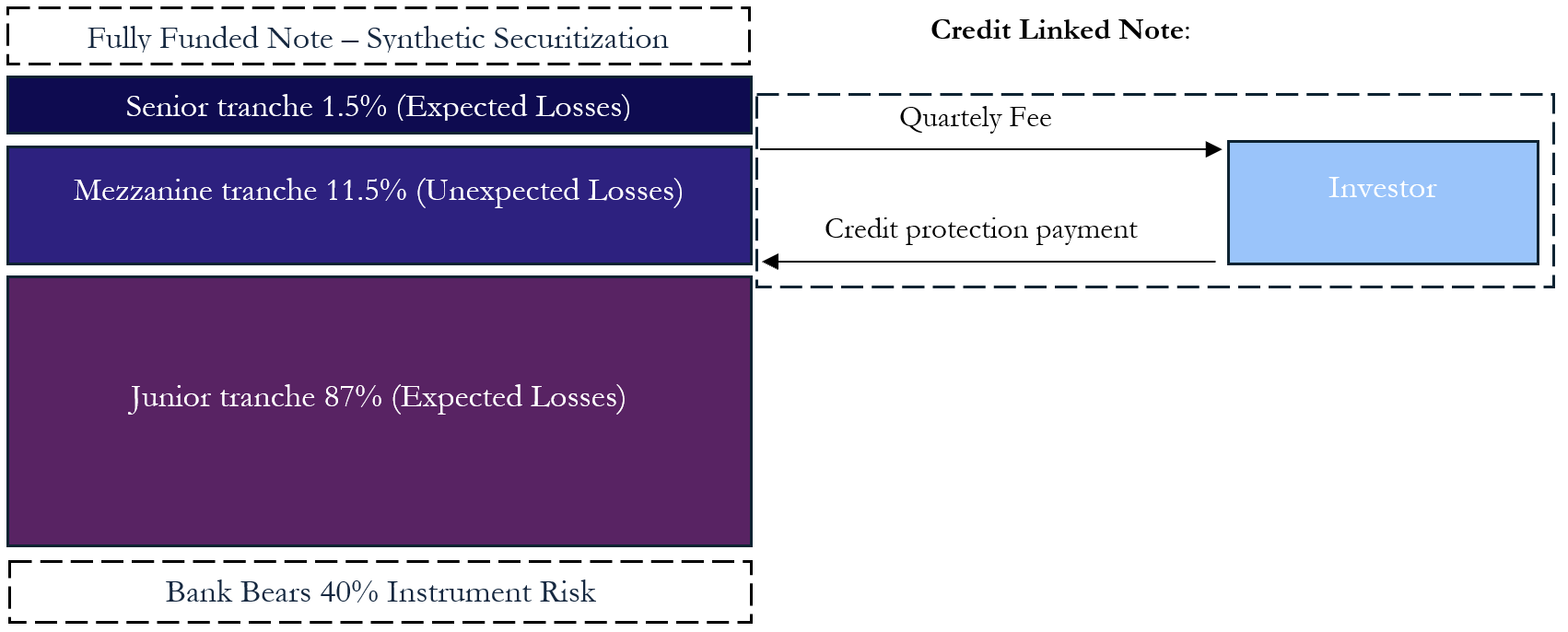

The bank structures a synthetic security which contains multiple tranches, each representing different levels of credit risk. The lowest-risk tranche might be retained by the bank, while higher-risk tranches are passed on to investors:

- Junior Tranche: Has the highest percentage of default probability but risk is priced in accordingly.

- Mezzanine Tranche: Riskiest tranche due to possible unexpected losses from the banks perspective.

- Senior Tranche: Has the lowest risk and is only affected if defaults exceed the losses absorbed by the junior and mezzanine tranches.

The capital structure gets modified by the following process :

- A bank is looking to free capital and begins analysing pools of credit risk. It decides to do an SRT, where it plans to transfer a portion of that risk. The underlying loans will remain on its balance sheet and assets are not sold, only credit risk is transferred.

- The bank finds an asset class, (usually capitally risk intensive) they then take an identified subset of that pool, put into synthetic securitization, they tranche up or securitize that risk and find a 3rd party willing to bear that risk for repeated payments, like an insurance contract.

- Generally speaking, the bank will then keep 1.5% of cumulative portfolio losses which from a regulatory perspective are called expected losses. They sell the mezzanine part so the next 11.5% which would be considered the unexpected losses, and they also retain the very remote senior levels of loss so 87/88% of loans after credit protection is exhausted. By selling the risk in the mezzanine, a bank can unwind around 60% of the unexpected loss risk of a transaction, leaving the bank with only 40% of the remaining risk in the actual instrument left.

Different asset classes, and different geographies will have different structures.

The bank then engages in a credit derivative contract, such as a credit default swap (CDS) or more commonly for SRTs a CLN (Credit linked note) that works much like a bond. Thanks to the transfer in credit risk, the bank no longer needs to hold as much regulatory capital against this portfolio. Through the SRT, the bank has freed up capital for other investments or lending. This transaction is frequently used for banks to open new lines of credit with clients while also keeping previous loans on its balance sheet.

If loans in the portfolio suffer a default event (bankruptcy, failure to pay, or restructuring), the bank must notify the investor by issuing a credit event. The protected tranche is written down by the amount of the realized loss, transferring the loss to the investors. However, depending on the underlying asset, the time taken to determine a loan’s final loss can be months or years. Thus, most SRTs incorporate the concept of estimated loss: if the realised loss differs from the estimated one, there is a true-up that can go in either direction depending on the size of the difference. However, the banks run counterparty risk in case where the investor/3rd party fails as well as the loans default then the bank would bear a huge loss.

Moreover, some SRTs include a replenishment period: for an agreed-upon period, banks can add new loans to the portfolio as old ones mature. This allows banks to transfer even more credit risk to investors depending upon the eligibility criteria, most common of which is that new loans share the original loan’s credit characteristics.

Generally speaking these transactions are programmatic issuances and transaction typically reference assets that the banks likes and want to grow, and they look for tools to support that growth. Banks face many constraints, they have many stakeholders – balancing all those stakeholders becomes an incredibly difficult job in this day and age and an SRT is a tool the banks has to grow and appease those stakeholders.

Recent deals we have seen are Apollo acquiring more than half of Deutsche Bank’s significant risk transfer on a $3bn (£2.2bn) leveraged debt portfolio a high-risk portion of the $420m of bonds was priced at 10.5 percentage points more than the secured overnight financing rate. Meanwhile, a mezzanine portion of $120m, which is intended to absorb losses, was priced at a spread of 3.75 percentage points over the benchmark rate. Morgan Stanley Selling Bonds Tied to More Than $4 Billion of Private Loans, the underlying loands are called subscription lines, which are credit lines typically extended to private equity and other private market funds to help them manage liquidity.

Banks Perspective

For banks, there are three ways to deal with the increased RWA imposed on some of their business areas. First, they can completely shut the business in question and retrench from that market. This has happened in some formerly bank-dominated finance areas such as especially mid-market leveraged lending, which is now largely dominated by different types of private credit / direct lending funds. However, as banks want to continue keeping most of their business, this is not a solution for many parts of their lending practices. Therefore, banks must find other ways to deal with the increased capital weights, which is either some form of increase of capital or some form of decrease of risk weights that does not involve exiting the respective market. Capital increases can be done in the form of keeping earnings on the balance sheet instead of distributing them to shareholders through dividends or buybacks or issuance of equity or deeply subordinated debt instruments such as additional tier one bonds. All these options are unfavoured by banks as long as there are cheaper forms of capital as they would be dilutive to shareholders. This leaves the option of decreasing the risk weights without closing the respective business, which can be done via SRTs.

Target sectors for these types of transactions are those where banks still have significant interest in keeping the business relationship while facing regulatory headwinds on the RWA side. These can generally be split into two categories: concentrated portfolios of single large exposures and granular portfolios of small exposures. The concentrated class mostly comprises of corporate, SME, project finance and commercial real estate loans, whereas the granular class mostly comprises of consumer loans such as auto, student or buy-now-pay-later loans and mortgages. Especially for the granular assets, many banks used securitization as means of de-risking in the past, with the main difference to SRTs lying in the special purpose vehicle structure and the size of the stake the banks retain in the respective credit.

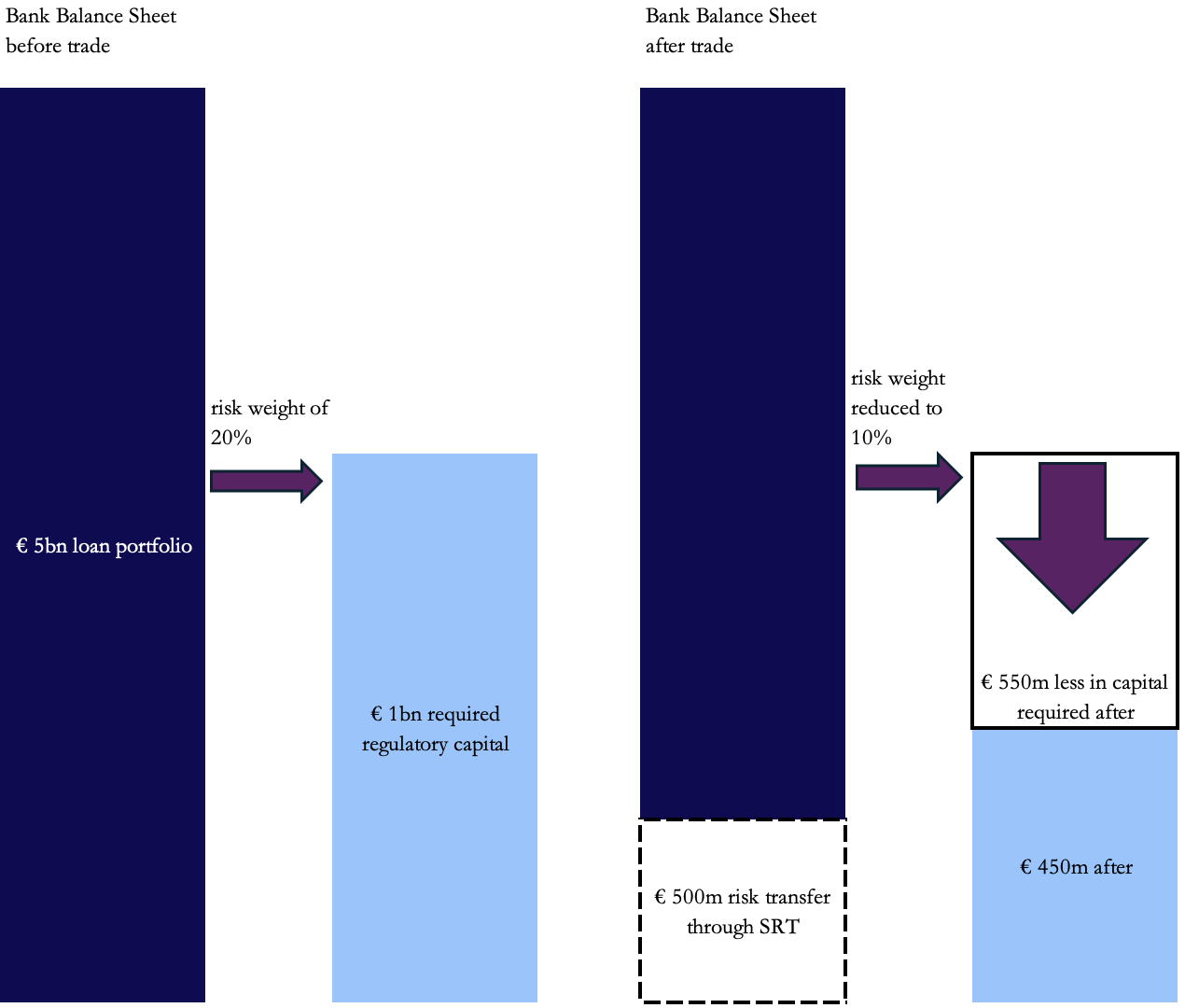

A simple example for the economic benefit of SRTs for the bank is as follows: If a bank holds a 5bn loan with a risk weight of 20%, it needs to put up 1bn of capital. If it now uses a SRT that hedges the first 0.5bn of that loan and reduces the risk weight by 10%, it only has to put up 0.5bn of capital for the exposure. This simple example swaps capital of the bank with the SRT note one to one and it is economically speaking smart for the bank to pursue the transaction unless its cost of capital (cost of equity or in some cases cost of AT1 bonds) is higher than the spread paid on the SRT note. This transaction effectively reduces the bank’s regulatory capital requirement by €550m, as shown in the image. The SRT transfers the riskiest portion of the portfolio (€0.5bn) to investors, leaving the bank with a lower-risk exposure. This reduced risk weight translates directly into lower capital requirements while allowing the bank to retain economic ownership of the loans.

In addition to the regulatory relief that SRT transactions can provide, there is also one other significant driver behind banks turning to the SRT market. Post Global Financial Crisis, many regulators and lenders alike have moved towards shifting risks from banks towards other financial institutions (often called shadow banks) that do not take deposits. With this move, banks’ business models have drastically changed from originating and then keeping credit risks to solely focusing on the origination in addition to other standard banking services such as e.g. cash management for firms or saving products for individuals. This is reducing bank’s interest income, as they now must pay spreads to the risk-taking parties such as SRT funds.The underlying motivation for banks is to use their capital in business areas where they still have an edge over alternative capital providers. For example, many banks have differentiated customer relationships and data that alternative capital has not build up on a comparable scale yet, but not really differentiated capital. In this regard, banks deploy their capital where it is most profitable (i.e. their most differentiated service offering) and not where there is more competition. With the ever-increasing importance of data, the banking industry is developing a new dynamic, as the processing of customer accounts and payments involves proprietary data to an extent found in few other industries. These dynamics resemble tech in the sense that the business model of banks becomes more of a winner-takes-it-all market, where the player that is quickest to develop its technology and scale its relationships to collect the most data is the most successful. However, despite of years of huge investments in technology especially by the major banks, this trend is still very new and it remains to be seen how it will shape classic banking in the future. On top of this, over the medium term, the decrease of credit risk taken by originating banks themselves should even out financial results, as hits from the very cyclical credit risk is instead borne by alternative capital. The combination of those two aspects puts banks in a place of capital-light, recurring revenues and high margin business that has been favoured by capital markets and could increase banks’ usually rather low valuations.

Investors Perspective

The investors in SRTs come from two different angles depending on the underlying credits: If the portfolios are very concentrated with large single exposures, investors go for deep analysis of each underlying credit and usually come from the classic lending / credit field, whereas with very granular portfolios, investors focus on the statistical analysis of metrics on the portfolio level and rather come from the structured credit space. While the portfolio composition, sector and regional focus may vary, SRT investors usually aim for generating strong coupon payments with little expected defaults and do not plan on extensive workout or even loan-to-own tactics. The default-adjusted return expectations are usually in the 7-15% range and cover up to 15% of the underlying loan portfolio risk.

In addition to the more quantitative parts of the analysis mentioned above, the major concern, and also, possible risk mitigant is the incentive alignment between the final risk taker and the bank. If the bank originates bad loans, this will negatively affect the performance of the SRT note and thus, the bank should be incentivized to minimize its losses. The importance of this aspect can be understood having a look at the securitization practices before the Global Financial Crisis, where banks tried to load up mortgage-backed securities as quick as possible to generate origination fees without any incentive to limit underlying risks as they usually tried to not keep any stake in the final SPV. With SRTs, the banks always keep on holding the largest part of the underlying loan portfolio which decreases the risk of misalignment of interests a lot compared to the Global Financial Crisis. However, it still has a strong impact on the returns of SRT notes if the default rate of the portfolio comes out at 3% or 5%, so investors need to make sure there are effective incentive alignment mechanisms especially granular portfolios, or have strong conviction on the underlying credits for concentrated portfolios. One important example of such incentive situations is that many funds only invest in SRTs for core business areas of banks as they do not want to hedge risks of legacy portfolios where banks just run down exposure sitting in the books with no interest in continuing the business area.

Will SRTs lead to the next GFC ?

After the crash of 2008, the words synthetic or securitization have made regulations intrinsically nervous and is one of the major reasons, in our view, why SRT have been getting so much negative attention for regulators.

As a financial instrument SRTs and Credit default swaps have key differences and are used in different ways, which is what leads us to be believe it won’t cause any major negative implications to the economy.

Difference between SRT and CDS:

The first essential difference that is realistically most important, is how the instruments are used; in 2008 CDSs were used as a way for speculative investors to make uncapped leveraged directional bets on contracts. SRTs on the other hand have traditionally been used for banks to truly hedge credit risk from their balance sheet, bigger banks will tend to use them to open new lines of credit with existing clients and SME and smaller banks have been using these instruments for a path to growth as we have seen banks business models evolve. Fundamentally, CLNs are not asset-backed securities. CLNs are simply unsecured bank debt for which the return of principal is dependent on the performance of the collateral. They represent a general obligation of the bank issuer where the investor has agreed to reduced payments from the issuer in the event that the borrowers on the underlying assets default.

Secondly, the distribution of credit risk in this system is further spread out than it was in 2008, the structure we saw at the time was a number of highly levered counterparties like Lehmann brothers or AIG and no diversification in the market in general. SRTs if anything are a solution to this problem, hypothetically transferring credit risk from banks (highly levered entities) onto investors with locked up long term capital and low levels of leverage. Traditionally this is true with the majority of buyers of SRTs being long term, buy-and-hold investors. Where this has recently been criticized by the BOE for example is in regards to hidden pockets of leverage. Some firms like private credit firms will buy an SRT and back-finance the trade to boost the returns, effectively rendering the SRT useless if it is viewed as an instrument that takes out leverage from the banking system in general. Leveraged products like these could potentially cause negative-feedback loops like we saw in the economy in 2008.

Thirdly, when it comes to counterparty risk, most of the deals are fully funded where investors put up all the cash day 1 and fully collateralized the bank for the life of the transaction, unlike bank exchanges of 2008 where underlying credit risk portfolios were just swapped for counterparty risk of the investor instead, creating hidden pockets of leverage. Members of the Federal Deposit Insurance corp. were quoted saying “Any counterparty investing in SRT using bank-provided leverage should be prohibited, full stop.” as “If a bank’s lending against the SRT instrument as collateral, you’re clearly not transferring the risk outside the banking system,” However, in general these transactions seem to be too few and far between to cause any real threat to financial stability.

Finally, to use the CLN structure that has become more popular, a bank must request and receive written approval from the Federal Reserve (in the U.S.) under a reservation of authority, for the bank’s specific transaction structures. These approvals are “facts and circumstances”-based, and only the bank receiving written approval may rely on that approval—put differently, for better or worse, a bank cannot structure its transactions to meet the requirements of an approval issued to another bank without requesting and obtaining its own approval from the Federal Reserve. This clunky process currently limits scalability of these transfer transactions,

Overall, much of the SRT and CRT market was very informed on the negative parts of CDS, and the majority of the financial system is quite heavily invested on avoiding another global financial crisis.

0 Comments