What is a SPAC?

A Special Purpose Acquisitions Company (SPAC) is a shell company set up by investors with the only purpose of raising money through an IPO in order to eventually acquire another company. They are also known as “blank-check companies” since they generally don’t have a merger target when they are formed.

These companies have no commercial operations, their only assets are typically the money raised in their own IPOs. Once the IPO raises capital (shares are usually priced at $10 a share), that money goes into an interest-bearing trust account (usually short-term U.S. treasuries) until the SPAC’s management team finds a private company looking to go public through a merger or an acquisition. SPACs usually have 2 years to identify and complete an acquisition, otherwise, the SPAC is liquidated, and investors get their money back with interest. Once the acquisition is completed (with SPAC shareholders voting to approve the deal), the SPAC’s investors can swap their shares with shares of the merged company or redeem their SPAC shares to get back their original investment, plus the interest accrued while that money was in trust while the SPAC sponsors typically get about a 20% stake in the final, merged company. When the business combination is completed, the target company becomes a public company.

Therefore, a SPAC can be considered as a concrete alternative to traditional IPOs and after the COVID-19 outbreak, it is arguably the hottest asset in the U.S. of late. More details about how a SPAC works can be found in our previous article SPACs: The IPO Killer? – BSIC.

From 2020 to 2021

SPACs have been around since the 1980s and often existed as a last resort for small businesses that otherwise had money raising difficulties on the open market. But recently they have become more prevalent due to extreme market volatility due to the global pandemic.

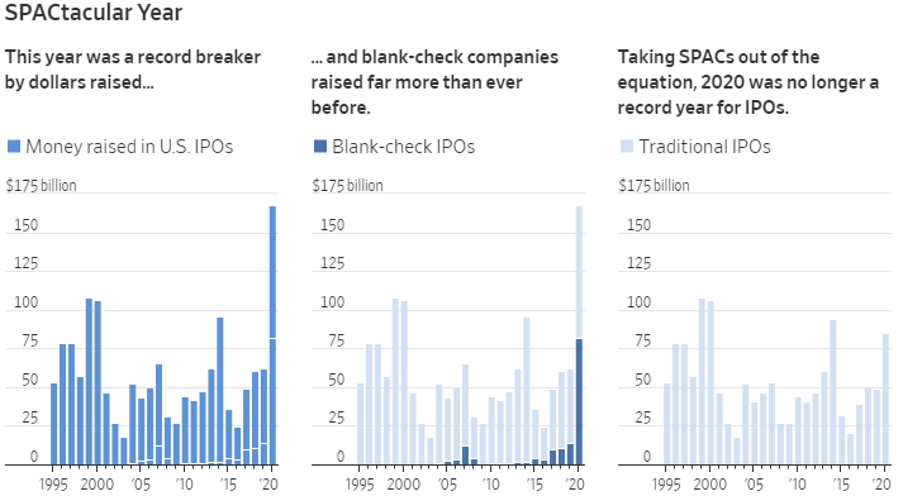

2020 marked a turning point for SPACs, which now make up most of the growth in the U.S. IPO market compared with past year levels. In 2020, SPACs have raised $83.4bn in gross proceeds with 248 IPOs and an average size of $336.1ml, surpassing the record $13.6bn raised in 2019 (raised from 59 IPOs). The 498% year-over-year jump in proceeds raised by SPACs this year outperformed the traditional IPOs in 2020. Back in 2007, the last boom for SPAC IPO volumes, SPACs made up about 14% of the IPO market versus 50% of the market share in 2020. This validates SPACs’ booming prospects.

Source: Dealogic

However, 2020 was not a one-off. With more than seven months until the end of 2021, initial public offerings of U.S. SPACs in the recent weeks surpassed the $83.4 billion raised in 2020. The dizzying growth of what was once a dark stagnation of capital markets reflects the popularity of SPACs as an alternative vehicle to traditional IPOs.

But things can’t be all good all the time.

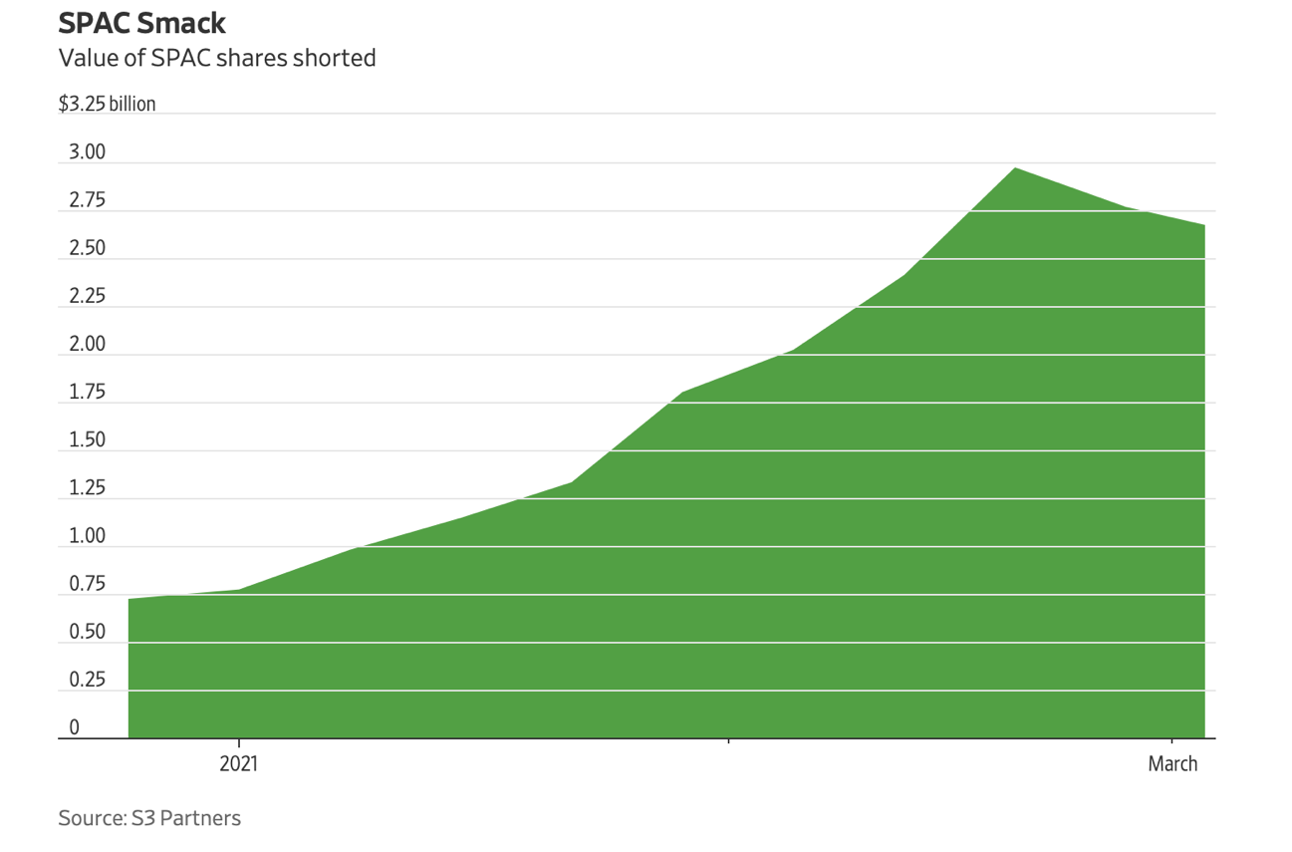

The red-hot industry is facing a number of challenges. With over 400 deals currently looking for targets, good quality companies are few and far between. SPAC’s IPO shares, many of which have experienced speculative trading activity, proved vulnerable to overall market volatility. Meanwhile, higher interest rates are making these growing companies – which are often pre-turnover and pre-cash flow – far less attractive. These companies often rely on future earnings, and if rates continue to rise, they will be more vulnerable than larger, more mature tech names. They don’t have solid balance sheets and sometimes they don’t even have a business. All these concerns are proven by the fact that the dollar value of bearish bets against shares of SPACs has more than tripled to about $2.7bn from $724m at the start of the year.

Source: S3 Partners

A deep look into the dark side of a SPAC

To fully understand why bearish bets are growing rapidly on this type of asset, we analyze the common and uncommon weaknesses that emerge from SPACs and which short sellers are leveraging.

Dilution is probably the most known problem that a listing via SPAC has. It is the situation that occurs as a result of the increase in the number of shares of the company (usually a capital increase); the profit distributed by the company will be divided over several shares and therefore, with the same total profit, but with more shares, EPS will decrease.

In a SPAC there are two main causes of dilution: the first due to the “sponsor promote”, i.e. the shares that the SPAC sponsor receives for putting together the deal, and the second one due to warrants that are given in addition to common shares during the IPO of a SPAC and can be exercised after the merger (usually at a price of $11.5) creating more shares. Both the sponsor promote and the warrants contribute to the dilution by creating more shares and decreasing EPS, therefore each stock is worth less and as a result, the price per share due to these two phenomena will inevitably tend to fall as volumes increase. Let’s work out an example to simplify these two issues and apply them to a SPAC: assume a SPAC issues 100 shares through its IPO (this is known as the float) and will use these 100 shares to buy 10% of a target company. Each share then equates to 0.1% of the target company before any dilution. The first source of dilution is the sponsor promote, this is traditionally about 20% of the float or 20 shares in our example. So now there are 120 shares representing 10% ownership of the target – meaning that each share equates to 0.08% (0.1/120×100) of the company after the promote. The second, and typically the biggest, source of dilution are warrants. If the share price settles above $11.50 (the price we assume at which warrants are exercisable after n. years) up to 2 years post merger, the warrants play their part. And because exercising warrants increase the float, they cause dilution. The lower the warrant coverage, the greater the intrinsic value of a common share. Looking back at our example we assumed that the SPAC shareholders owned 10% of the company post-merger. The approximate dilution caused by exercising warrants for SPACs with different degrees of warrant coverage is:

Dilution is by far the largest burden for the company going public through SPAC. The table can be explained also as the cost of going public through a SPAC with 1:1 warrant coverage is 10% of your company while the cost of going through a SPAC with 1:5 warrant coverage is 2%. Obviously, the fewer the warrants in circulation the more each share is worth, however, in order to quickly attract new investors and when the SPAC sponsor does not intend to invest in the long term but simply to speculate in the short term, the warrants coverage can reach 1:2 or 2:3.

Another intrinsic issue of a SPAC is the so-called “principal-agent problem”. It is easy to understand what the different growth prospects are. On the one hand, we have the management of the target company convinced that it wants to protect its business in the long term and redeem it solidly and profitably. On the other hand, we have investors who do not want to give up their sponsor promotion or warrants and see the target company as an opportunity to crown their investment and lock in profits. Typically, investors give the SPAC money for up to 24 months while it looks for a merger target. In return, they get the right to withdraw their investment before a deal goes through that minimizes any loss on the trade. This means that even if SPAC shares fall, investors are protected by the right to withdraw. Throughout the whole process, they can sell warrants. On the other hand, when SPAC shares soar, warrants grow more valuable. This trade for investors is a rare example of a mainstream investment that has limited pitfalls and it also strongly contributes to diverging the common objectives between the investors and the target company management.

The two main weaknesses described above are common to most SPACs. While they represent one of the major causes that pushes these companies into the sights of short-sellers, they are not enough. When a short position on a SPAC is announced, the report targets a specific aspect of these companies: their fundamentals. In the SPAC market it seems that no revenue is no problem. In the last two years, there has been a trend of companies going public before they’ve even generated their first revenues. These businesses are selling a vision rather than a proven track record, and they see listings via SPAC finance their project. That’s the EV case with Lucid Dreams and Nikola leading the way. What happened with Nikola is particularly interesting and helps us understand how the quality of some target companies is often very poor. Nikola Corporation is a US company that announced a series of zero-emission vehicle concepts based on hydrogen and indicated its intention to produce them in the future. In June 2020 it went public through a SPAC. The futuristic concept and the revelations of the first models attracted a large number of investors and after the first months the market cap reached 30bn (Ford Motor Company was at $33bn at that time). However, Hindenberg Research did not take long to investigate the business of the company which not only had no revenues yet, but had not even produced a single truck. On 9/20/20 Trevor Milton, the founder of Nikola, resigned as executive chairman following allegations of fraud. Being unprofitable is a big problem, not having revenues even bigger. The stock market is not suitable for listing “ideas”, although the SPACs make it appear that this is possible.

A further test that short-sellers like to apply before confirming the shot is: would this company have succeeded in listing through a traditional IPO? This question seems complicated, but it’s not, particularly because some target companies before listing via SPAC tried a traditional IPO but failed. That’s the recent case of WeWork, that filed for an IPO on 8/19/19 but soon afterwards it faced intense scrutiny of its finances and leadership from investors and the media, bringing to various postponements and the final step-back. In March 2021, the American real estate company announced their intentions to go public through a SPAC with a $9 billion valuation and merge with BowX Acquisition Corp. Therefore, why can a failed IPO become a successful SPAC? Surely SPAC processes are less regulated, but this does not lighten doubts and ease short-sellers’ concerns.

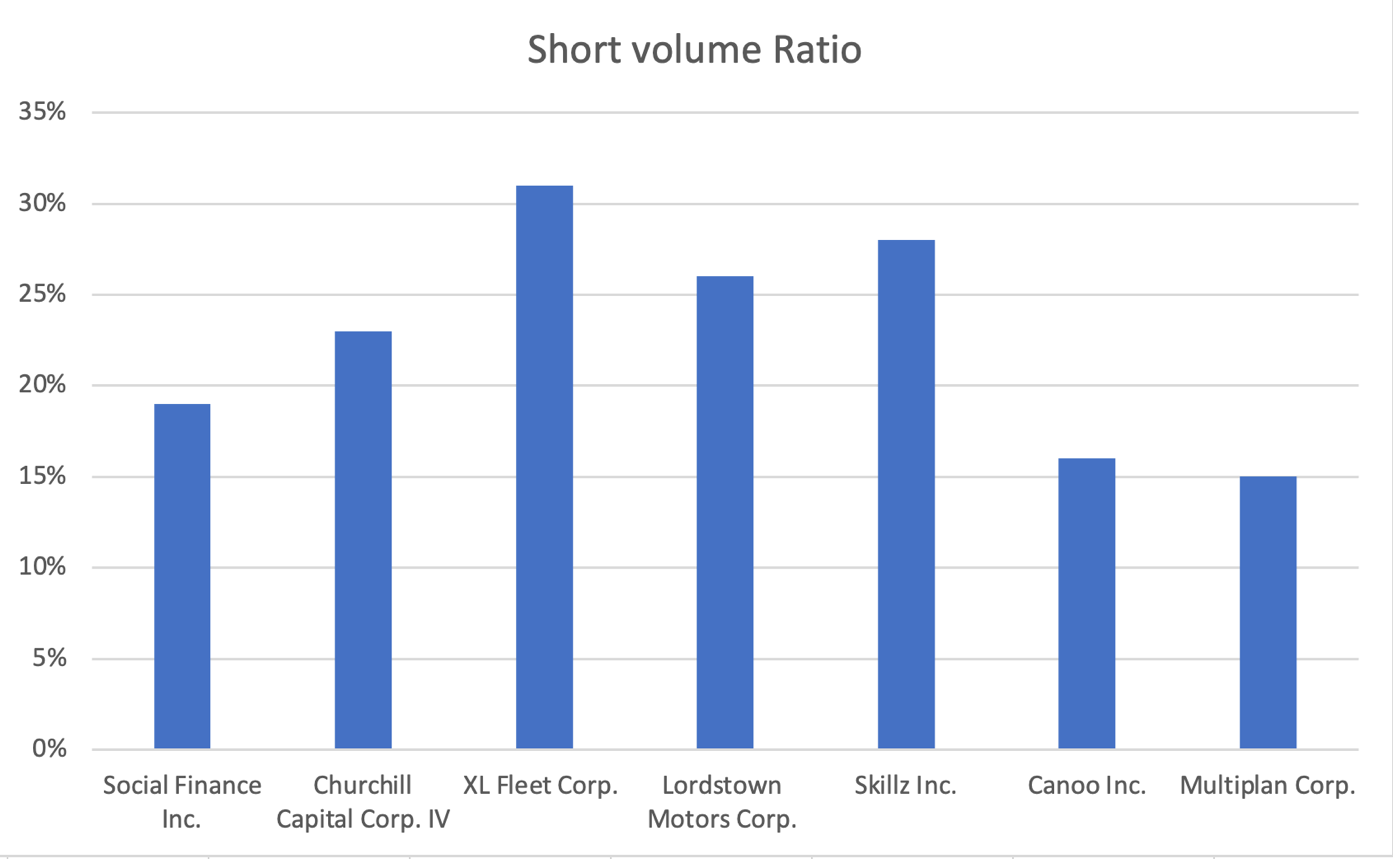

The last point to analyze in a SPAC before finally opening a short position is the market capitalization of the post-merger company. If it is very high, that means that their shares are easier to borrow and thus, from a financial point of view, it will be also less costly, since the stock loan fee is lower. That’s why the SPACs with higher market caps like Multiplan, Lordstown Motors and Canoo are the most shorted.

Summing up all these points, if you’re looking to open a short position on a SPAC, your analysis should surely start from looking at the “sponsor promote” and the warrants coverage to understand how much dilution the target company will suffer, and then understand who the investors are and if they are going for a long-run investment. Finally, take a look at the core business of the target company (if it is already working or not) and its market cap to see if the short would be too costly or not. If your prey reflects all the characteristics described above, then we think it’s time to go short.

External factors

Hedge funds keen on short selling don’t limit themself to a deep look at the targeted company, their analyses also include external factors of the market and how they influence the company; this also applies to SPACs shortage. First, we need to look at projected annual inflation for the next few years. In the U.S., headline inflation rose to a 12-month pace of 2.6% in March against economists’ average estimate for a 2.5% increase. This close difference scared market participants, causing the shares of high-growth companies with low liquidity to fall, and SPACs were among them. With the projected annual inflation rate in the U.S. set to rise until the end of 2023 (data by the International Monetary Fund), weaker SPACs will struggle to survive on the market and create opportunities for short-sellers.

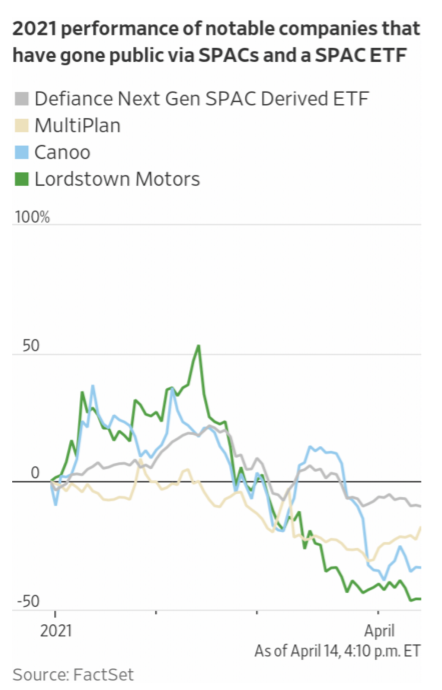

Then we need to look at the overall performance in both the bear and the bull market. Considering the last couple of years, investors would have earned a higher return by longing the S&P 500, which yielded 52% compared to 45% with SPACs. Swapping to a bear market analysis, worries do not diminish: a monthslong rally in stocks lost steam recently in March amid a broad sell-off in technology and high-growth companies. The Indxx SPAC & NextGen IPO Index (index targeting newly listed SPACs) fell about 17% from mid-February to March 10, while the Nasdaq Composite Index declined about 7.3% over the same period.

Source: FactSet

Conclusion

So, is the SPAC party over? Our answer is no, at least not yet. At the moment, most SPACs are highflying and someone needs to bring them down to earth, but this is not true for all of them. The SEC, largely silent on SPAC through all 2020, has recently implemented some measures to stop or at least regulate the party. It warned some post-merger companies that they have to restate their financial results because of the way they accounted for warrants, in particular these last should be classified on their balance sheet as a liability rather than as equity. The primary purpose of a SPAC was to be an alternative to traditional IPOs, managing to obtain better pricing, less time to go public and the opportunity to have the guidance of an expert investor/sponsor. Nowadays this idea faded up a bit: most of the private companies see going public via SPAC merger as an easier way since with their fundamentals they would never succeed in making a traditional IPO and sponsors just see these companies as a way to quickly make profits without taking much risk. Probably in the short run, we will see lots of post-merger companies not being able to survive on the market, but this will also help to clean up all the “garbage” companies that went public too early. Nevertheless, our contention is that, in the long-run, SPACs with some improvement in the points cited above will hold their position as a concrete alternative to IPOs, and the path to make them healthier and more sustainable has already been undertaken by some respectable investors like Bill Ackman with Pershing Square Tontine Holdings (PSTH:NYSE), where he made most of the warrants non-detachable (discouraging the arb community and encouraging long term investors) and rearranging the compensation for SPAC sponsor to 6.21%.

0 Comments