Introduction

Private Equity firms are known for investing in all types of businesses. Ranging from pet clinics and cookie brands to power transmission lines, over time funds have expanded their investment horizons to different asset classes. In the early 2000s private equity firms began investing in higher education, more specifically in universities, and they have achieved significant returns. Moreover, funds have also been invested in educational service companies as test providers and companies that provide data, proving that education is an investment that provides exceptional returns. On the other hand, most universities are non-profit organizations. While one may think that as non-profit organizations, they would tend to run a lean balance sheet, some universities have amassed massive endowments thanks to its alumni’s generosity, and others have even started raising capital through 100-year bond issuances. Overall, it is clear that higher education has become a business, which may completely differ from the original plans that existed when the first institutions were founded in the 11th century.

Universities: History

Universities date back to the 11th century with the founding of the University of Bologna by Catholic monks in 1088. Soon after, institutions such as the University of Paris and the University of Oxford were formed. These first universities were primarily public or church-affiliated, designed to educate clergymen and state officials. Gradually, rulers and city governments began to create universities in order to satisfy a thirst for knowledge. Universities expanded their academic scope and student populations and are now central to societal advancement.

In the 19th century, we began to see a shift towards private universities, particularly in the United States, as industrialization increased demand for more diverse and career-focused higher education. Alongside private institutions, the first for-profit education institutions emerged which focused on vocational training and entrepreneurship. Bryant & Stratton College, founded in 1854, is an example of such an institution.

The birth of the modern for-profit university model occurred in 1976, with the establishment of the University of Phoenix by Apollo Group [NYSE: APO], offering distance learning and flexible programs for working adults. The early 2000s saw massive growth for for-profit universities due to the rise of online education. Companies such as Apollo Group, Perdoceo Education Corporation [NASDAQ: PRDO] and Laureate Education [NASDAQ: LAUR] led the way during the recession years, with for-profit university enrolment peaking around 2010.

One could also argue that for-profit higher education institutions are not the only moneymaking universities, but that non-profit private institutions are also able to generate ‘profits’ through their endowment funds.

What are Endowment Funds?

Endowment funds are investment portfolios which operate by using capital from donations. Their purpose is to fund charitable and non-profit organisations such as churches, hospitals, and universities. What differentiates endowment funds from the usual investment funds is that the fund is a non-profit organisation, and the value of the principal is untouched. The profits achieved through the endowment funds’ operations are usually used to support certain causes and donors might impose restrictions on the usage of the donated money (e.g. invest only in companies that respect ESG standards). A further characteristic of an endowment fund is that due to its non-profit nature, the money can be held indefinitely.

There are 4 types of endowment funds: Term Endowment, Restricted Endowment, Unrestricted Endowment, and Quasi Endowment. A Term Endowment fund is characterised by the fact the principal or a part of it cannot be used for the fund operations. Instead, it can be invested to generate investment income, which the organisation can use. The principal becomes available after a certain time or triggering event which is established by the donor. A Restricted Endowment works similarly to the Term Endowment, but the donation can be only used for specific purposes established by the donor. An Unrestricted Endowment, on the other hand, doesn’t have any limits on how the money must be spent. Lastly, the Quasi Endowment Fund is characterized by the fact that it’s the Board of Directors that decides how to allocate the money and not the donors. Furthermore, there is no legal obligation for the fund to exist indefinitely, which means that the initial donated principal can be used at some point. Although there might be some usage and withdrawal restrictions, the Board of Directors may end them and utilize them for a specific purpose.

Endowment Funds used by universities allow them to achieve several goals. They allow them to diversify their income streams as the universities’ income is impacted by changes in enrolment, donor interest, and public support, hence providing stability. Although the returns in the financial markets also heavily fluctuate, institutions implement guidelines e.g. spending rates which aim to reduce economic fluctuation and generate a stable stream of income. Furthermore, endowment funds allow colleges to support need-blind admissions and provide the same level of service at a lower cost. As we can see from the table below, Harvard’s endowment fund has been a major source of income for the university.

Source: Harvard University Financial Report, BSIC

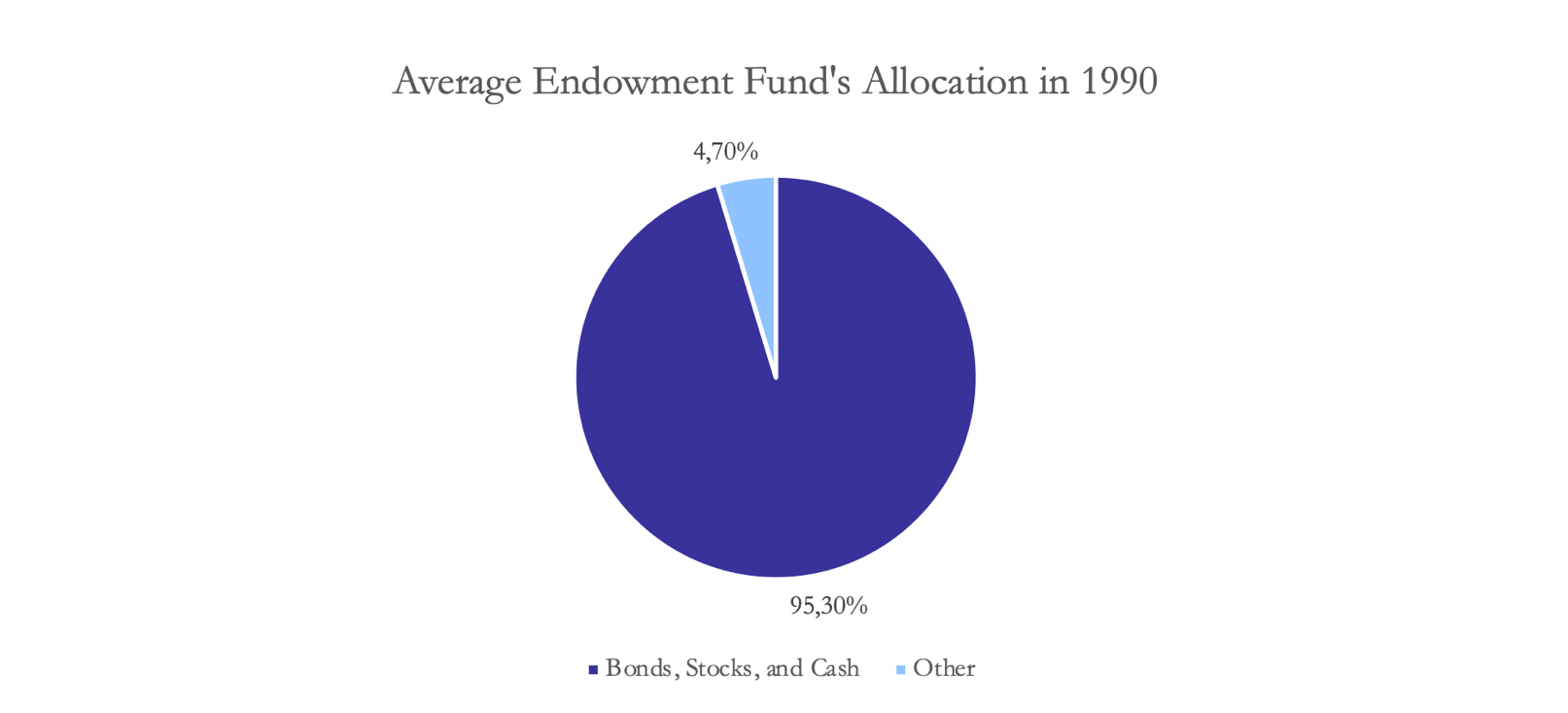

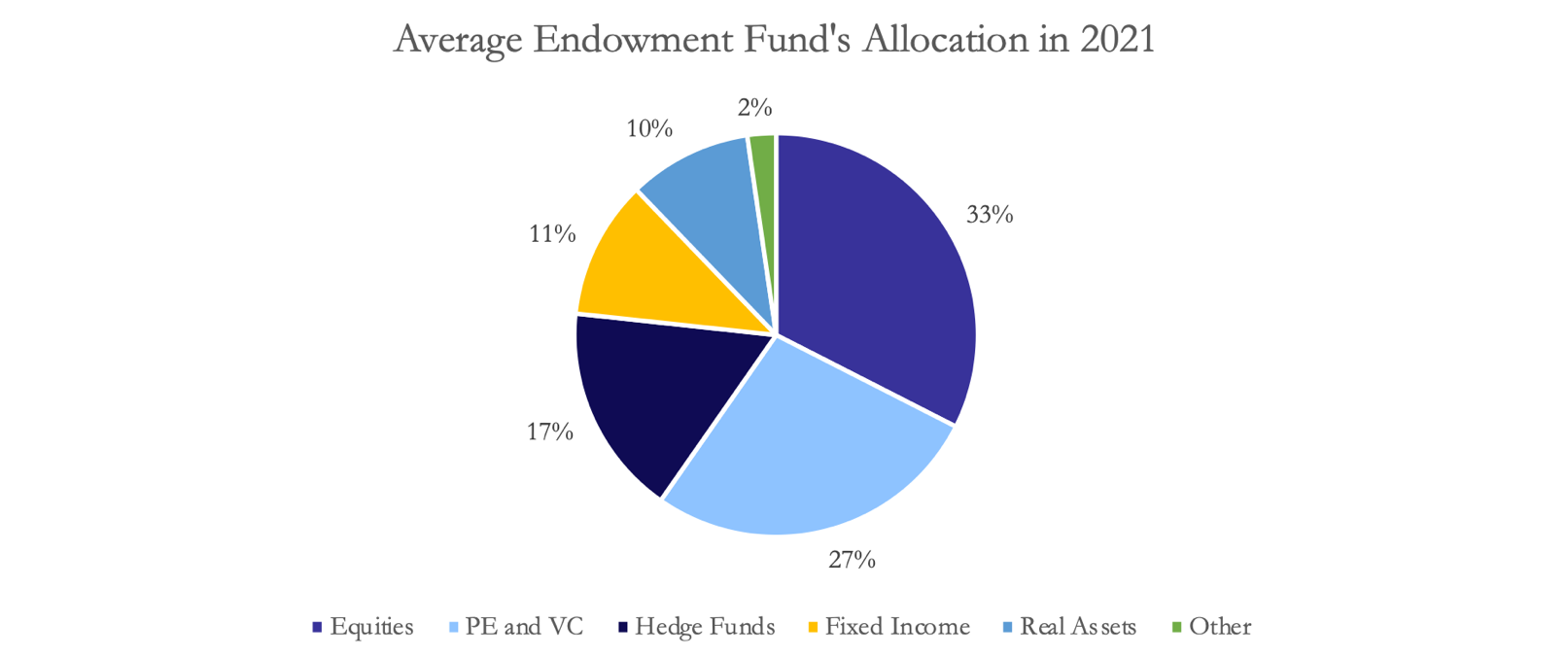

Endowment Funds’ strategies have also evolved during the last 25 years. In 1990 an average institution was investing in more traditional assets, with 95.3% of its endowment allocated in stocks, bonds, and cash. Currently, we can see a shift towards alternative assets such as Hedge Funds, Private Equity, Natural Resources, and Real Estate.

Source: NTSE, BSIC

Student activism has a long history starting at least in the 1970s when students demanded divestiture from companies that would benefit from the South African apartheid. Currently, as geopolitical tensions arise, and the fight for climate change intensifies, many student activist groups started to demand that endowment funds be divested from companies which are considered unethical. In 2021, after 10 years of activism, Harvard decided to divest from fossil fuels completely. The divestiture also included any indirect holdings of fossil fuels from Private Equity funds. Furthermore, after the breakout of the Israel-Hamas war, student activists demanded divestiture from any companies that profit from the conflict.

Private Equity Investments in Education: Universities

Private equity (PE) investment into higher education spiked during the years following the 2008 recession, with high numbers of students flocking to higher education to increase their employability in a brutal job market. At the time, PE firms recognized the growing global demand for higher education as well as the industry’s stable cash flow and potential for strong returns.

University tuition fees generate stable, recurring revenues which PE firms can capitalize on. A 2018 research paper found that profits at a US for-profit institution triple after a buyout, primarily due to an increase in tuition fees by about fifty percent of the average total tuition at US community colleges. In the United States, PE firms are able to raise tuition thanks in part to the availability of government-backed student loans. Another reason for massive PE investment into universities in the late 2000s and early 2010s was due to the rise in online education. Investing in for-profit universities that primarily offer online learning allows PE firms to benefit from a reduced need for physical infrastructure – this enables rapid scaling at lower marginal costs.

The landmark deal that set the trend for higher education buyouts was the take private of Laureate Education by a consortium of Private Equity firms including KKR [NYSE: KKR], Citigroup Alternative Investments and Sterling Capital for $3.8bn in February 2007. The acquired firm is the parent company of Laureate Education Universities which operates institutions in Mexico and Peru, with previous operations in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, New Zealand and Switzerland.

Following the buyout, Laureate engaged in massive global expansion under PE control and soon became one of the largest for-profit education networks in the world, operating institutions in over 20 countries with a total enrolment of about 550,000 students. Despite the massive growth that Laureate experienced, the profitability of the PE investment became more uncertain over time for various reasons.

Firstly, PE-owned for-profit universities in the United States led to lower graduation rates, higher student borrowing and lower repayment rates. This induced greater regulation and scrutiny on for-profit institutions, leading to their decline. Secondly, a decline in the public perception of for-profit universities impacted their enrolment and revenue streams. Thirdly, the highly leveraged buyout of Laureate added financial pressure to the firm.

In 2017, Laureate went public again through an IPO, raising $490m in an effort to recover value. This marked a partial exit for its PE investors, although they retained a significant stake in the company. By 2020, Laureate began selling off some of its international assets to refocus on a smaller core of institutions. The sales of its operations in Brazil to Ser Educacional [BVMF: SEER3] for $724m were part of a strategy to pay down debt and return value to KKR and other PE shareholders.

The overall profitability of the PE consortium’s investment in Laureate Education had mixed results, despite the IPO and asset sales providing some capital recovery. These sorts of mixed results have characterized many PE investments in university institutions and higher education. For example, the private equity firm Altas Partners acquired the University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences (USAHS), a for-profit health sciences university, for $364.4m in April 2018. In July 2024, the Altas Partners signed a definitive agreement to sell USAHS to Perdoceo Education Corporation who expects to pay $142m to $144m in an all-cash deal.

Despite a downturn in private equity ventures into the higher education industry in the mid-late 2010s compared to their peak, there has been a recent surge in investment led by the Swedish firm EQT [OMX: EQT] which has invested in some of the largest deals targeting higher education services since January 2023. Firstly, it participated in the take-private of Japan-based Benesse Holdings Inc., which is Japan’s largest provider of education services across all ages. In a deal worth JPY 208bn, representing a 45% premium on Benesse’s closing price on the Tokyo Stock Exchange Prime Market, EQT aims to capitalize on increased Japanese demand for adult training and reskilling to further accelerate Benesse’s growth.

More recently, EQT announced in April 2024 that it had reached an agreement with British PE firm Permira to acquire a majority stake in Universidad Europea, a leading higher education platform operating in Spain and Portugal. In a deal valuing Universidad Europea at $2.2bn, including debt, it represents the first-ever investment into education by EQT’s infrastructure arm. Moreover, the deal represents great value for Permira – who invested funds into the higher education institution to fund their expansion – as they are expected to generate a 5x MOIC through the stake sale.

Now, EQT’s vision for Universidad Europea is to apply its in-house digital team to enhance the company’s online and hybrid learning presence. The Swedish firm looks to ride the growth that Universidad Europea experienced under Permira with revenues, EBITDA, and student enrolment growing by 2x, 2.5x, and 3x respectively. According to Anna Sundell, Partner within EQT’s Infrastructure Advisory team, this investment aligns with the firm’s goal of becoming long-term active owners in companies providing essential services to society.

This leads us to the question of whether private equity ownership in universities is inherently beneficial to society. From a purely financial standpoint, we cannot argue that PE-owned universities benefit from the industry expertise and capital that PE firms bring to the table. Student enrolment and revenues experience exceptional growth under PE guidance, generating greater profits for these higher education institutions. Nonetheless, the adverse effects of private equity investment into universities are clear.

Firstly, PE ownership results in downwards pressure on the quality of education and services at these institutions. For example, the leveraged buyout acquisition of Education Management Corporation (EDMC) by a consortium of PE firms in 2006 created a hot-housing working environment for recruitment staff. Although student enrolment nearly doubled under private ownership, employees recount how day-to-day operations shifted from a commitment to students’ success into an environment focused on hitting enrolment targets.

Secondly, numerous studies and papers have found that private equity buyouts have led to a six per cent decline in graduation rates in the United States, as well as lower student loan repayment rates. Increased tuition fees under PE ownership have led to a nine per cent fall in repayment rates compared to non-PE owned for-profit institutions. If we take the case of EDMC, the rate at which students defaulted on their loans almost doubled between 2008 and 2009.

Private Equity Investments in Education: Beyond Universities

Private equities have ventured not only into university ownership, but over the recent years they have also purchased companies that provide services affiliated to higher education. In 2019, Inflexion Private Equity acquired Times Higher Education (THE) from TPG Capital, another PE fund. Times Higher Education is the world’s leader in university data and rankings, with institutions, students and governments utilizing the information to benchmark and assess higher education institutions around the world. As of 2019, the company provided services that included raw data, data analysis, and consulting, among others, to over 700 clients, as well as had over 30 million visitors on their webpage for the year. Moreover, in January 2022, THE, owned by Inflexion, acquired Inside Higher Ed (IHE from Quad Partners, a fund specialized on investing growth equity in the education sector. IHE is an online media site that provides independent news and analysis, industry insights, and other tools and services focused on higher education to over 25 million yearly users. This acquisition brought together two leading brands in higher education, with over 55 million yearly users. Furthermore, this was just one of the five add-in acquisitions that Times Higher Education has made while being owned by Inflexion. Moreover, as of April 2024, there were rumours that Inflexion was looking to exit its investment.

Additionally, in April 2024 Nexus Capital Management, a US-based private equity firm partnered with the ACT, in a deal that would make the non-profit college admission exam provider transition to a for-profit company. The acquisition of the company raises some concerns about the transparency and accountability of the exams being administered, as well as resulting in significant changes for assessment test companies after years of changes in the college admissions processes. Moreover, the new ownership will try to expand the company’s service offering into outside of the traditional college admission processes.

Through these 2 examples, it is possible to see that funds see education as a whole as a good business opportunity. Investing in universities is highly profitable for firms, and investments in the annex services should be no exception. However, doubt arises on if the investments in the databases and test providers will be also beneficial to their users, or if, as with universities, the funds will receive the majority of the benefits.

100-year bonds: A new source of University Funding

100-year bonds are securities issued by companies with high creditworthiness due to the extremely long duration of the bond. From the company’s side, it is an opportunity to achieve a considerable amount of financing with a very small cost of capital. This is further enforced when interest rates are low as the company can lock in low yields for the entire duration of the bond. Companies can also decide to pay back the bond if a certain duration has been reached giving them more flexibility (the Walt Disney 100-year bond can be repaid after 30 years (2023) of its issuance). From an investor’s perspective, they can invest in 100-year bonds to fulfill duration-based goals in their portfolio. Secondly, investors might speculate that the bond will not actually last for its whole duration. Lastly, the 100-year bonds can be used by investors to pass generational wealth.

The biggest 100-year bond issuance by a university was conducted by the University of Michigan [UM] in early 2022. UM issued $2bn worth of bonds, from which $1.2bn were century-bonds priced at a 4.45% coupon, 2nd tranche consisting of $500mn 30-year bonds with a coupon of 3.5%, and lastly $300mn bonds were issued as green bonds, also with a 3.5% coupon. The funds will be used to finance several renovation and construction projects on the Ann Arbor campus, such as 3 new undergraduate residences, continuing the work on the Michigan Medicine Clinical Tower, and replacing the Central Campus Recreation Building. By utilizing favorable market conditions UM gained access to cheap funding due to the lower interest rates, which will be locked in for decades. Furthermore, the green bonds will allow UM to pursue its goal to have a carbon-neutral campus by 2040. The demand for this type of asset is underlined by the fact that initially, UM planned to issue between $500mn to $700mn, but the demand was so high that UM managed to raise $2bn.

Another notable university that has decided to issue 100-year bonds is Oxford University in 2017. The fundraising has proven once again the big demand from investors for this type of asset as the university managed to raise 3 times more than initially expected, increasing the amount from $250mn to $750mn. The strong demand allowed the institution to borrow at very favorable terms, achieving a 2.5% coupon. Lastly, a very interesting bond issuance is the one from Rutgers University, which raised $330mn of 100-year century bonds at a 3.92% coupon, with the aim to finance an internal bank. Thanks to the high demand from investors for 100-year bonds, universities have easy access to capital on favorable terms, allowing them to fund projects while providing high standards of education without increasing tuition.

Conclusion

Overall, it is safe to say that higher education has become a business. Universities, while they may be non-profit, behave just as any large corporation does as a result of the emission of bonds and their significance for financial markets because of the size of the endowment funds. However, while education as a business may be good for private equity funds and their investors, users do not necessarily benefit. On one hand, the cost of tuition in universities has increased significantly over the last years, making higher education an even more exclusive resource. Also, in some cases, PE ownership in universities has led to a decrease in the quality of education, a more hostile working environment for the staff, and even a decline in graduation rates. Consequently, education has become a very large and profitable business, but this has led to quality being compromised, questioning the original purpose of higher education.

0 Comments