Private markets, once the exclusive domain of institutional investors, are undergoing a structural transformation. As technology, regulation, and investor behaviour evolve, access to traditionally illiquid asset classes like private equity, credit, and infrastructure is widening. What was once a closed ecosystem of pension funds and endowments is now being opened to retail investors, driven by both necessity and innovation. The democratization of private equity marks a profound shift in global capital markets, challenging the boundaries between public and private finance, and redefining how wealth is built and shared.

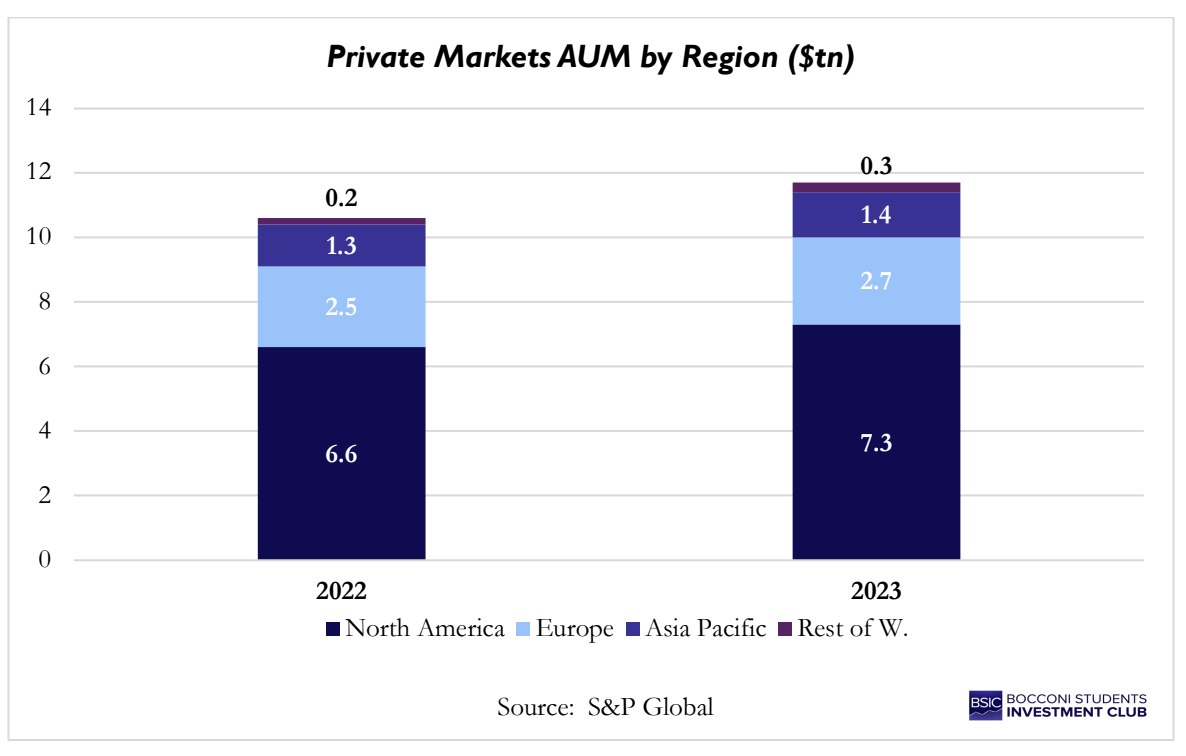

Private markets is an umbrella term given to asset classes that are not traded on public exchanges. They encompass anything from an equity stake in privately held companies (across all stages of developments), to private credit, infrastructure, and real assets. According to S&P Global, AUM in private markets totalled ~$12tn in 2023, an increase of 9% from 2022 and 19% higher than 2021. This growth shows no sign of slowing, with the industry projected to increase a further 26% this year and 51% by 2027, solidifying the sector’s rise to a mainstream asset class.

Private Equity (PE) is the largest component of private markets, accounting for a share well over 50% of total assets according to S&P Global. At its core, it entails the ownership of a stake in private companies, but in practice, the term typically refers to PE firms that pool funds from investors, and use them, often with leverage, to acquire or invest in private businesses. A large subset of private equity is Venture Capital (VC), which focuses on early-stage companies with high growth targets, making up ~11% of private-market assets. Generally, it is a high-risk, high-reward form of investment that not only finances but also provides strategic guidance to founders. Alongside company ownership and venture funding sit Infrastructure Investments. They refer to physical assets that are essential for the functioning of society, ranging from utilities, toll roads and airports to hospitals or schools. These projects are typically long term, capital-intensive investments, attracting institutional investors such as pension funds, seeking stable, predictable, and often inflation-linked cash flows. As these assets are generally uncorrelated with “standard” markets, they provide investors a source of diversification within broader portfolios. Lastly, Private Credit is a form of lending and borrowing, which takes place outside the traditional banking system and now accounts for 15-20% of private-market assets. This area has seen rapid expansion over the past decade and is now approaching $2tn in AUM.

The Problem of Private Equity

There is growing evidence that companies are remaining private for longer periods. According to Renaissance Capital, the median age of companies listing in 2025 is 13 years, up from 10 years in 2018. This could reflect a structural shift in how businesses are funding their growth. Private capital is enabling companies to raise funds, whilst avoiding the regulatory burden and scrutiny which comes with being listed. For founders, remaining private preserves their control and long-term goals, shielding them from the volatility of public markets. This trend can also be underscored by the rise in potentially “permanent” private firms, such as SpaceX and OpenAI.

However, there might be a more pragmatic explanation. Many PE firms are struggling to exit their holdings, due to the volatile IPO markets and mismatches between sellers’ expectations and buyers’ valuations. According to S&P Global, PE exits fell to a 2-year-low in Q1 2025, and according to PwC, an analysis of PitchBook Data from 2024 discovered that 4000-6500 PE exits had been cancelled or delayed in the previous two years due to both inflation and rapidly rising rates. Following a period of cheap financing and inflated deal values, higher rates and tighter financing have created exit bottlenecks. The PE industry is faced with scarcer opportunities, higher financing costs, and exits are proving difficult, all of which reinforces the longer-private trend. There is a sense that institutional investors are getting frustrated with slower payback times being observed in the market, which could hinder future fundraising. The fear is that existing institutional investors are and will continue to allocate less capital to the sector in the future as they dislike the slow rate of capital deployment. As they receive less payouts they have less to reinvest.

Furthermore, PE is suffering from a “dry powder dilemma”. According to Bain & Company’s 2025 PE Report, global buyout firms are sitting on ~$1.2tn in dry powder, committed capital which is not yet deployed; nearly a quarter of that was pledged more than 4 years ago. Whilst this may sound like a strength, it in fact signals that firms are struggling to deploy capital efficiently in an environment with intense competition and high financing costs. Bain’s report also notes that “with the exception of a spike in 2021, the amount of capital returned to investors is not keeping pace with the industry’s increasing scale”. Just a decade ago, distributions, the share of invested capital being paid to investors, sat at 29% of total fund NAV; now that figure is only 11%, despite AUM buyouts tripling over the same period. The ‘buy-improve-sell’ cycle, which once underpinned PE economics, is now clogged. With exits slowing, carried interest falling, and fundraising momentum cooling, declining to just $1.1tn in 2024, down 24% year on year, many are reducing commitments to new funds. Thus, the growing possibility of raising funds from retail investors will help offset fee compression and diversify PE’s revenue streams. It can completely reshape the liquidity profile of the PE model, with less reliance placed on traditional institutional investors.

Barriers to Entry

Barrier to entry materializes in retail investors historically being restricted from participating in private markets, due to a mix of regulatory, structural and practical barriers, but these are beginning to loosen. In the U.S., the Securities Act of 1933 and the Investment Companies Act of 1940 created a clear divide; public markets were open to all investors but subject to strict disclosures and registration requirements, while private markets were reserved for “accredited investors”, based on the assumption they can afford the greater risks. Similar regulatory hurdles existed across Europe, where regulators held the view that only professional investors could properly assess these assets and bear the potential losses.

Today, regulation is beginning to catch up. Around the world, authorities are cautiously softening restrictions which have limited private markets to traditional investors. For example, in the U.S. an executive order in August 2025, encouraged broader access to alternative assets within 401(k) retirement plans, opening the door for PE allocations within diversified retirement portfolios, if oversight and liquidity thresholds are respected. Additionally, the SEC has been exploring the option of expanding accredited-investor definitions and permitting limited exposure to private funds through certain regulated vehicles. This confirms a structural redefining of the fiduciary boundaries and allows large asset managers to expand their outreach to retail investors, as seen in the recent partnership between KKR [NYSE: KKR] and Capital Group or Blackstone’s [NYSE: BX] increased investment in its global wealth strategy. These changes could unlock portions of the $29tn U.S. retirement-savings market to be invested in private assets. In the EU, the European Long-Term Investment Fund (ELTIF 2.0) regulation, implemented in early 2025, have removed the minimum €10,000 investment and the 10% retail cap, enabling platforms like Trade Republic to offer fractional private-market access to retail clients under stricter disclosure and liquidity rules.

Secondly, structural constraints have also kept investors out. Private-market funds often impose high minimum commitments, sometimes $5m+, and tend to prefer stable capital from institutional investors with long-term horizons. Managing thousands of small investors creates administrative and compliance costs, from KYC and anti-money-laundering checks to the logistics of obtaining multiple investors consent during amendments. But technology is simplifying processes, driving the democratization of PE. Fintech platforms are providing digital onboarding and fractional ownership with ease, utilising tokenized securities which can automate compliance steps. Tokenized funds are securities which use blockchain technology to represent ownership of a fund through digital tokens. They also include digital settlement systems which make it far easier to offer private-market products at scale. Several U.S. banks and fintech’s have already successfully tested tokenization of traditional assets, reducing cost and operational difficulties

The surge of retail interest in private markets is largely driven by the fear of missing out, or rather, the fear of having already missed out. Retail investors are beginning to comprehend the value created before companies list. By the time they are public, valuations are often inflated, and a large proportion of potential growth has already been captured by early-stage investors. Thus, for retail investors, buying shares in a public company is increasingly seeming like “arriving late to the party”. The desire to gain access to early-stage, exponential growth opportunities is what is fuelling retail investors’ interest in private markets, opening the door for platforms like Trade Republic and Robinhood [NASDAQ: HOOD] to pioneer new models that bring institutional-grade private equity exposure to individual investors.

Trade Republic’s Partnership with EQT and Apollo

The regulatory and perception shifts described above, with the increased interest in private markets, have crystallized in Europe in the partnership between Trade Republic, EQT, and Apollo. Strategically, this move is the logical culmination of Trade Republic’s evolution into a marketplace of financial services. Over its history, the company has evolved from a zero-commission brokerage to a broader wealth platform that encompasses savings and credit cards. The venture was announced in September 2025, with Trade Republic aiming to make private markets accessible to the retail domain. This marks a paradigm shift in the relatively opaque world of private equity.

Diving into the architecture of the partnership, EQT will contribute its newly launched EQT Nexus ELTIF (European Long-Term Investment Fund), which consists of a diversified PE vehicle that mirrors the firm’s flagship strategies across sectors such as technology, healthcare, and consumer. Apollo has rolled out three Evergreen ELTFs (investment funds that allow for continuous capital investment and periodic redemptions without a fixed end date), offering retail-friendly leases to private and global opportunistic credit, and secondaries.

The funds’ structures are innovative as they fuse traditional fund architecture to fintech distribution with ELTIF 2.0 serving as the legal spine of these developments in Europe. At the fund level, EQT and Apollo run regulated, closed-end investment vehicles, while at the platform level, Trade Republic acts as a distributor and fractional intermediary. Retail investments are pooled in omnibus accounts and rooted into ELTIFs, allowing investors to purchase fractional units. Subscriptions and redemptions are processed monthly, while the NAVs are struck on a monthly or quarterly basis, depending on the manager. The internal fund marketplace, developed by Trade Republic, enables users to sell positions monthly, subject to counterflow and platform rules due to liquidity constraints typical in private investments. The hybrid design of the platform effectively introduces a quasi-liquid layer on top of inherently illiquid assets. The ability to “sell monthly”, is more complex than that of a traditional exchange. The internal marketplace that Trade Republic developed consists of a closed, platform-managed system where liquidity depends on the balance of new inflows and redemption requests (functioning like public equity with low liquidity, where exits depend on active share float). Prices reference the fund’s latest NAVs. These are updated infrequently and often lag the underlying assets and capital structure changes in the portfolio. In normal conditions, the synthetic liquidity may function smoothly; however, in cases where redemptions exceed inflows, Trade Republic may gate transactions and delay settlements of price redemptions at a discount, thus echoing the challenges of semi-liquid fund models.

A further point to note is that Trade Republic mentions the absence of additional platform fees. Yet, the all-in costs are determined directly by the ETF’s own management and performance fees as well as its operating expenses, with a distribution economics embedded at the fund level. Critics have pointed out that the effective annual drag could approach 3-4%, comparable to traditional private wealth vehicles, undermining the democratization narrative. Furthermore, valuation smoothing and delayed reporting can obscure risk, creating a behavioural trap for unsophisticated investors who may misinterpret the stable NAV as lower volatility.

Until recently, the notion that a retail investor could commit €1 to a private fund would have been unthinkable. By combining the fintech rails, fractionalization, and ELTIF 2.0 regulation, Trade Republic has drastically lowered the barriers to entry for retail investors. If the model is successful, it could serve as a blueprint for the realization of private markets across Europe, similar to how ETFs democratized public markets two decades ago. The move has prompted competitors like Scalable Capital and Revolut to study similar offerings, while asset managers such as Ardian explore ELTIF 2.0 vehicles for mass distribution.

Robinhood’s Public-Market Gateway to Private Equity

Simultaneously, the U.S. is also seeing a new wave of financial innovation in private markets focusing on publicly listed vehicles. This is spurred by increased PE interest across the population, as well as regulatory changes that have made breakthroughs in generalized access to alternative investments on 401(k) pension plans. The clearest case is that of Robinhood’s recent Robinhood Ventures Fund (RVI), consisting of a closed-end, publicly listed vehicle designed to give investors exposure to high-growth private companies.

Like Trade Republic’s origins as a brokerage service, Robinhood has built its name as an online brokerage platform seeking to bring retail investors into public markets. Thus, its next logical step is to “democratize private markets” as it has done with public markets. Founded in 2013 by Vlad Tenev and Baiji Bhatt, Robinhood began as a mobile-first, zero-commission brokerage platform designed to “let everyone trade” by delivering a simple user interface. By 2024, Robinhood had expanded its user base to around 23m active users and was moving beyond trading. They sought to build a comprehensive wealth ecosystem, which now includes services such as Robinhood Retirement, Robinhood Gold, and its new managed portfolios and credit offerings. Thus, the platform’s growth has mirrored a generational shift towards increasingly giving retail investors access to previously restricted asset classes. In this context, the launch of RVI represents not only the launch of another product offering but Robinhood’s entry into asset management, by attempting to deliver a fee-based wealth product built on a diversified portfolio of private companies.

Robinhood seeks to increase customer retention through long-duration products and diversify revenue, as their business model has evolved to being solely dependent on payment for order flow in transactions and would benefit from a fee-structured wealth platform. Unveiled in September 2025, RVI is registered under the Investment Company Act of 1940 and once approved by the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC), it will trade on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) under the ticker symbol RVI, allowing investors to buy or sell shares as they would with any other security. Unlike mutual funds or ETFs, RVI does not redeem its shares directly. Liquidity is also externalized, given that shares trade in the open market and prices can fluctuate at a discount or premium to the fund’s NAV, depending on market factors. Given this design, the fund does not face forced-liquidation pressures that plague open-ended funds in times of stress, thus allowing it to hold long-term illiquid assets.

The mandate of RVI is to invest in late-stage startups and pre-IPO companies across sectors being considered technologically transformative, for example AI or robotics. To achieve the planned exposure, Robinhood has developed a multi-channel strategy by building a portfolio through direct investments, private vehicles, secondary transactions, and using synthetic exposures in cases where direct ownership is restricted. Given its structure, RVI seeks to build a portfolio of companies that meet its investment criteria. However, as a non-diversified entity, it can only hold a concentrated portfolio.

The fund’s fee model mirrors that of traditional closed-end structures but incorporates additional layers typical of private market investments. Based on the preliminary prospectus, it indicates several key components. They include a management fee charged on net assets as well as acquired fund fees and expenses (AFFE), which represent charges from the underlying private vehicles in which the RVI invests. Notably, there are no incentive (performance) fees at the RVI level; however, carry fees may apply within the underlying investing vehicles for which analysts estimate that fee expenses could reach 3-4% (significantly higher than those charged on ETFs and mutual funds).

Diving into the liquidity dynamics of RVI, it follows an externalized structure in which the liquidity of the fund’s shares is entirely dependent on market demand, which means that during periods of optimism, shares may trade at a premium to NAV. During drawdowns, they may trade at a discount. The NAV of the fund is updated quarterly, which may lead to sentiment-driven volatility, where trades anchor to stale valuations or react sharply to updates. This creates a behavioural paradox where liquidity only exists if another investor is willing to take the other side of the trade, as opposed to regular retail brokerage functions usually utilizing market makers. Discount volatility might introduce a speculative element to the trading of the fund, as retail investors could treat RVI shares as proxies for sentiment on “innovation” rather than through their underlying fundamentals.

For Robinhood, the launch of RVI aligns with the current momentum, packaging private markets exposure in a regulated, SEC-supervised format that can integrate with retirement and retail brokerage accounts. Despite concerns over the structure of RVI, its launch represents the first time a U.S. mass-market brokerage has embedded institutional PE exposure within the retail investing space, thus symbolizing a new frontier in market democratization. If the product is successful, it would pioneer a new product category, consisting of publicly listed PE access funds. This sets a precedent for competitors to follow, as the boundaries of retail investing expand to new asset classes that have been historically restricted for institutional players.

Overall, the democratization of private equity represents not just a passing trend, but an important shift in global investing. As platforms like Trade Republic and Robinhood bridge the gap between institutional capital and individual investors, the mechanics of private-market access are being rewritten. Yet, accessibility brings complexity: liquidity constraints, valuation opacity, and behavioral risk remain fundamental challenges. Whether this new model delivers true inclusion or simply repackages exclusivity will depend on how technology, regulation, and investor education evolve. What is certain, however, is that private markets are no longer private; they are transforming into an essential part of the mainstream financial landscape.

References

[1] BNY Mellon, “The Rise of Private Credit,” 2025

[2] Tucker, Hank, “Private Equity’s $29 Trillion Retirement Savings Opportunity under Trump,” Forbes, July 2025

[3] McKinsey & Company, “Global Private Markets Report,” 2025

[4]BlackRock, “2025 Private Markets Outlook,” 2025

0 Comments