Introduction

Every course of Management or Business Administration covers organizational structure, simply because it is the cornerstone of every company. Some firms are very specialized and have well-established chains of command, therefore do not require an elaborate system of structures. Others have so complex and expansive activities that not even employees can fully comprehend them. Conglomerates belong to this category: Large, usually multinational business entities that unite firms in different industries under one corporate group. The concept is as old as corporations, but it grew especially dominant during the “conglomerate boom” of 1960s in the US. The economic environment was perfect then, specifically low interest rates and a volatile stock market created opportunities for the leveraged buyouts (LBO) of undervalued assets. Berkshire Hathaway [NYSE: BRK.A], one of the most prominent conglomerates, has its roots in this period as well, expanding the previously textile-focused company into the insurance industry in 1967. Some decades later, European business culture followed suit. German giants like Siemens [FWB: SIE] and ThyssenKrupp [FWB: TKA] entered numerous different fields through the 1980s and 90s, eventually becoming a conglomerate in every sense of the word with the acquisition of steel & mining company Hoesch AG in 1991 by the latter and the establishment of Siemens Financial Services in 1997 by the former. Although the rate hikes of 1980s put some strain on conglomerates, several of which had to spin-off assets or shut down, others marched onto the 21st century as some of the largest companies in the world. Advantages of diversification like reduced risk and the emergence of an internal capital market seemed to outweigh the disadvantages.

Recently, though, a robust reversal of fortunes seems to be taking place, as investors have been getting increasingly disheartened about conglomerates. In the last five years, the S&P 500 Index soared 117% while conglomerates like Berkshire Hathaway only gained 90%, Loews Corp. [NYSE: L] rose 34%, 3M Co. [NYSE: MMM] climbed just 6.4% and General Electric [NYSE: GE] saw a dismal decrease of 51%. In light of this underperformance, many companies are considering selling assets or breaking up, in order to flow with the current towards specialization. Just in the first weeks of November 2021, Toshiba [TYO: 6502] and Johnson & Johnson [NYSE: JNJ] announced such plans. Perhaps the most prominent, however, is the decision of General Electric to split into 3 divisions: Aviation, healthcare, and energy. Once the most valuable company in the world, GE failed to reap the benefits of being a conglomerate as it struggled to streamline its business despite several changes in management.

(Source: Bloomberg.com)

This article will first examine the reasons for the decline of conglomerates, then the breakups of GE, Johnson & Johnson, and Toshiba will be analyzed, and, finally, the future of conglomerates will be investigated.

The Decline of Conglomerates

It can be observed that the trend is stronger in conglomerates with more diversified lines of business. There are more “concentrated” conglomerates like Procter and Gamble [NYSE: PG] which operates numerous production lines for everything from shampoos to diapers and batteries, but their business can be categorized under the umbrella term of “consumer goods”. Another example is AT&T [NYSE: T] which offers services such as mobile services, cable and satellite television, broadband installation, and home security, all of which can be classified as “telecommunications”. These examples were eventually able to extract the synergies from their union of companies. P&G benefits significantly from inter-departmental distribution of innovation and economies of scale while AT&T offers bundles to customers, helped by their brand recognition. While these firms also took steps to specialize in key areas of business, they were not as drastic as the steps by the three key focuses of this article, GE, Johnson & Johnson, and Toshiba.

The worse performance of conglomerates is often summarized by one key word: The “conglomerate discount”, which can be defined as the tendency that a conglomerate will be valued less than the sum of its parts, is caused by a combination of a several factors.

First, if one business unit of a conglomerate is struggling, this tends to have a negative effect on the entire company, inflating the risk for investors. The effect is especially fierce if the group companies have high levels of exposure to each other through an internal capital market. Additionally, disappointing results from one division of the company are more newsworthy than satisfying results from another division, therefore reputational costs and role of the news media further amplify the negative news. This was partially responsible for the drawn-out fall of General Electric, whose finance and aviation divisions had to weather the storms of the 2008 financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic, respectively.

Second, the more diversified a conglomerate is, the more complex it becomes for non-professional investors to analyze and evaluate its finances, which adds a behavioral extent, as humans are fundamentally reluctant to engage with an unknown. Furthermore, valuing the individual sections of the business is also difficult since the only P/E ratio available is (usually) that of the parent company. The division may not even be performing in the same conditions with its competitors due to vertical integration as well as the aforementioned internal capital market, rendering relative valuation less useful.

Third, a very diverse set of subsidiaries require the management to spread their attention thin, hindering necessary expertise to develop. Additionally, adding another layer of bureaucracy slows some processes in the company, leading to inefficiencies. If there are no synergies to compensate these disadvantages, the structure becomes impractical. Furthermore, there might arise an agency conflict, as management favors a united company for higher bonuses and more prestige, even though it is not advantageous for shareholders. Moreover, finance theory suggests that diversification is not necessary at the company level since investors can freely diversify their portfolios.

As a result, the pressure from activist investors and PE funds to acquire specific business units is increasing on the topic of organizational structure as well. Recently, activist investment firm Third Point urged the Anglo-Dutch oil giant Shell to break up, which was covered by BSIC in an article last week. Notably, Third Point was successful in their previous attempt to break up the United Technologies in 2018. Since late 2019, New York based hedge fund D.E. Shaw has been pushing for the break-up of Emerson, an industrial conglomerate.

GE

American giant General Electric is bound to change the rules of its game after over 125 years of diversified services. In the wake of competitors like Siemens AG, DowDuPont, and Emerson Electric Co spinning off several divisions, historical conglomerate GE reversed its track and announced on November 9th its plan to form three public companies focused on aviation, healthcare, and energy. While the debate between fit and focused firms and conglomerates is still heated, with the newly Facebook convert Meta Platform Inc at the helm of the diversification scheme and Siemens as leader of the spin-off fever, GE seems to have a strong rationale backing each of its spin-offs.

The first step in the major GE split will be the tax-free spin-off of the Healthcare segment, which is planned for the beginning of 2023. GE expects to retain a 19.99% stake in the pure-play company which will be focused on precision health and critical patients. Then, a second spin-off of its energy sectors will take place in early 2024. GE Renewable Energy, GE Power, and GE Digital will be combined into one business that will position itself in the market offering the most efficient wind, gas, and steam turbines along with technology to digitize its infrastructures. Upon completion of this second transaction, GE will be an aviation focused company striving to innovate the flight industry while powering ⅔ of commercial flights. Overall, GE expects one-time separation and transition costs of about $2 billion and tax costs of less than $500 million.

For what concerns the major drivers of the transactions, using Trian Partners’ words: “The strategic rationale is clear: three well-capitalized, industry leading public companies, each with deeper operational focus and accountability, greater strategic flexibility and tailored capital allocation decisions.“ Trian was one of the major activist investors pushing GE to split-up and is enthusiastically following up on its advice. Nevertheless, the split will also mean higher control over GE’s debts. As a matter of fact, the company has been selling assets for several years and the shrinking process was accelerated as current CEO Culp was asked to lead GE in 2018. Indeed, the company expects to shed over $75 billion of debt from the end of 2018 to the end of 2021.

It is also interesting to note that the three-way split might not end there. The decision, which was joyfully welcomed by the market with a 2.7% increase in share price upon announcement, has set the stage for a major private equity buyout of GE’s most attractive assets. The head of a large multinational buyout firm, as reported by the Financial Times, even talked about a “GE Store”, making a reference to the likely forthcoming GE assets shopping spree. The general sentiment is indeed that most assets could sell for a better price on the private rather than public market.

Johnson & Johnson

Healthcare conglomerate Johnson & Johnson is not planning to be second to GE and is following its competitors GSK and Pfizer in the effort to slim down to ride the wave of a booming post Covid-19 pharmaceutical industry. To keep up with the need for more efficient and dynamic big pharmas, the company announced on November 12th its decision to split the business in two and spin-off its consumer products division to focus on pharmaceuticals and medical devices. The market reacted positively as shares went up by 1.3% for the day, but the advance was still not enough to beat J&J’s 52-week high.

The consumer products division, mostly famous for its Band-Aids and baby shampoo but also for over-the-counter drugs like Tylenol, is set to spin-off in 18-24 months, most likely via a stock offering. The goal is to close a tax-free transaction and to keep dividends at the same level. The division, which is part of a $270bn sector in which J&J competes with consumer products producers such as Reckitt Benckiser and Nestlé, is expected to generate over $15 billion in sales. Its brands, among which we also find Aveeno, Neutrogena skin care products, and Listerine, reported 3.1 per cent organic sales growth in 2020 and contributed to less than a fifth of the $82.5bn revenue. Over half of group sales were delivered by pharma cancer treatments like Darzalex and Imbruvica. While the consumer unit business has acted as a drag for J&J over the past years, analysts overall agree that the split would allow the two new companies to be more focused and flexible.

The two divisions have indeed grown progressively apart in terms of marketing and logistics needed for selling products, both of which were strong reasons behind the historical 135 years old conglomerate diversification strategy. As the healthcare system started to face rapid changes caused by digitization and artificial intelligence, painkillers production and blockbuster drugs development processes diverged quite substantially. Outgoing CEO Alex Gorsky believes the transaction would bring “tremendous opportunity” as by separating the company can improve capital allocation and more agility. In addition, the announcement comes in a time in which the pharmaceutical industry is shifting towards slimmed down companies. As GSK and Pfizer formed a joint venture with their consumer health units, J&J followed suit with its two-way split announcement. The rationale is hence once again clear: fast following to create more focused and dynamic business entities that can singularly become leaders in their respective industries. One caveat worthy of note, however, is the accusation that J&J faced for its allegedly carcinogen talcum powder. The company indeed spent $1.4 billion to create a subsidiary to manage the lawsuit and put it into bankruptcy, but strongly denies the legal claims are tied to the decision to split.

Toshiba

On the other side of The Pacific, Toshiba, a century-old conglomerate faces new challenges, losing its international exposure and appeal. Once a global giant selling everything from PCs to Semiconductors and Nuclear technology, in recent years Toshiba has retreated from international markets to its home market of Japan, losing ground to Chinese competitors.

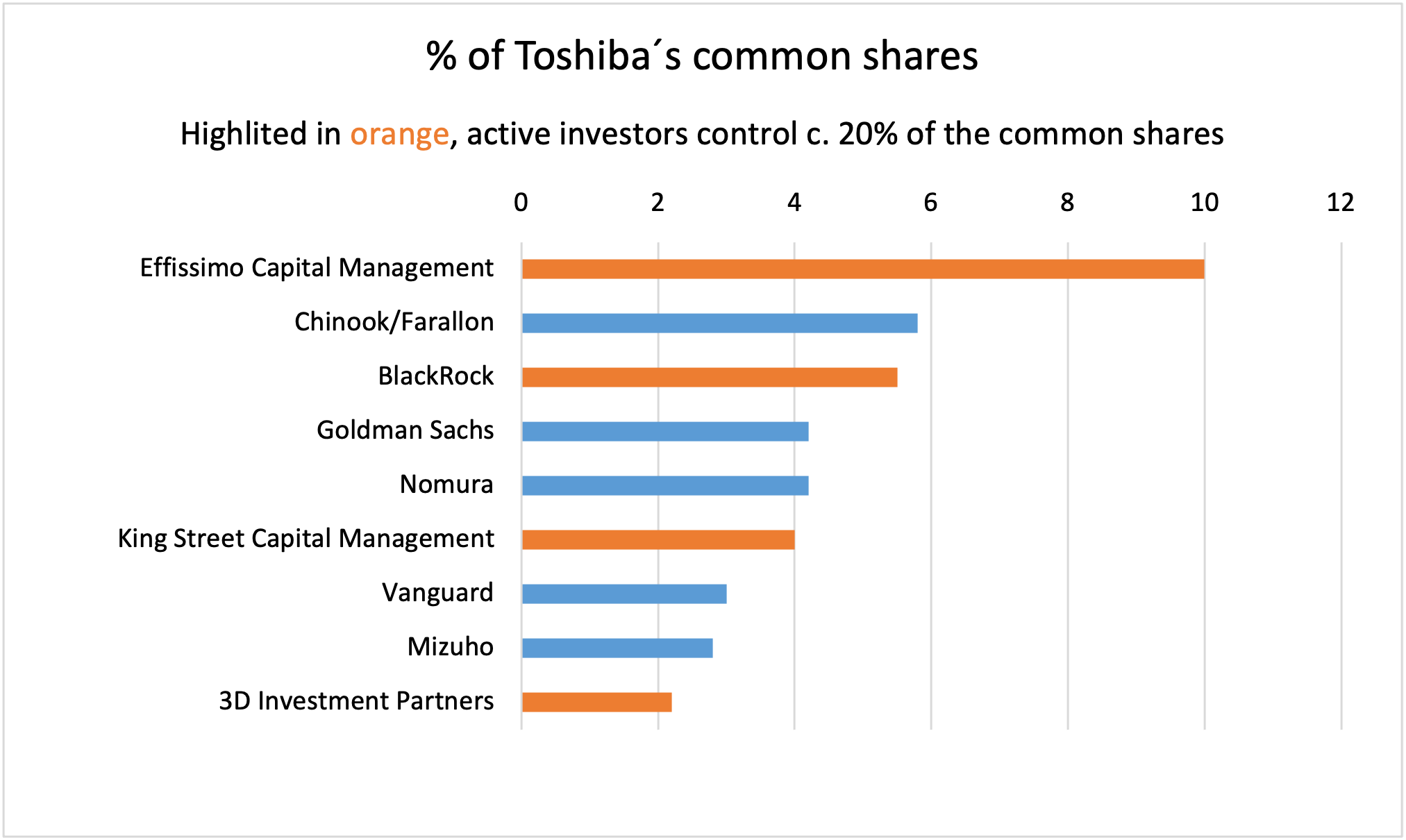

For the past years, Toshiba has experienced a wave of corporate scandals, started by allegations of financial statements fraud back in 2015 and followed by the failure of its United States nuclear business. In 2017 the 140 years-old conglomerate was on the verge of bankruptcy, being forced to sell its praised semiconductor business to Bain Capital for $18bn. These continuous failures have been the catalyst of internal turmoil, Toshiba´s board meetings becoming a “civil-war” between shareholders and executives. The board of directors has faced resistance from activist investors like the Singaporean investment fund, Effissimo Capital Management, with a 10% stake, which advocates for stronger corporate governance and more transparency on how decisions are made. In early 2021, activist shareholders triggered an independent special committee, with the task to investigate misconducts of Toshiba´s board, concluding that executives collided with the Japanese government and influenced voting behavior in the 2020 Annual General Meeting.

(Source: Toshiba 2020 Integrated Report)

Another task given to the special committee was to examine the option of reducing the burden of the conglomerate structure, having a few possibilities in mind: restructure and sell billions-worth of non-core assets, or allow Private equity funds to acquire parts of the business; CVC, an UK-based fund made a buy-out offer in 2021 to Toshiba for $20bn. The latter option might have offered activist investors a chance to exit, however it poses national security problems for Japan, as Toshiba´s businesses have an important stake in the Japanese nuclear energy production. After weeks of rumors, on the 12th of November, Mr Satoshi Tsunakawa, Toshiba´s chief executive announced a plan to split the company into three separate entities by 2023, a proposal that will be voted by shareholders in earlier next year and aims to deliver more customized services to address emerging needs. The decision was supported by a new preferential tax regime for spin-offs introduced by the Japanese government just recently.

The first company will focus on providing energy to electric power utilities across the full value chain and enhance infrastructure through investments in digital solutions, having an expected revenue of $18.3bn. The second company will produce semiconductors for automotive and industrial equipment, and High-capacity HDDs for data centers, having an expected revenue of $7.6bn. The remaining operations of Toshiba will function as an Asset-management fund, with the goal of monetizing the 40% equity holding in memory-chip business Kioxia, the world’s second-largest maker of flash memory chips, valued at around $20bn. The expected value of these three separate companies exceeds Toshiba´s current market value of $29.4bn, potentially creating additional value for shareholders. The separation of Toshiba will enable each business to tailor its capital for its specific needs, and target debt and equity investors for a more effective financing process. For shareholders, this will provide a huge array of investment opportunities and for management, it will enable more nimble decision-making through reduction of managerial layers. From a PE perspective, this will open the gates of a more transparent Japanese market and might lead to a buy-out of the devices company. After the announcement was made, Toshiba´s stock price increase by 1.5%. However, the uncertainty if shareholders will vote in favor of the breakup brought the share price below is pre-announcement level. The criticism of the transaction, coming from some activist investors, is directed against the decision to not run a formal sale process first, as some buyout funds were interested to acquire the whole company.

The Evolution of Conglomerates

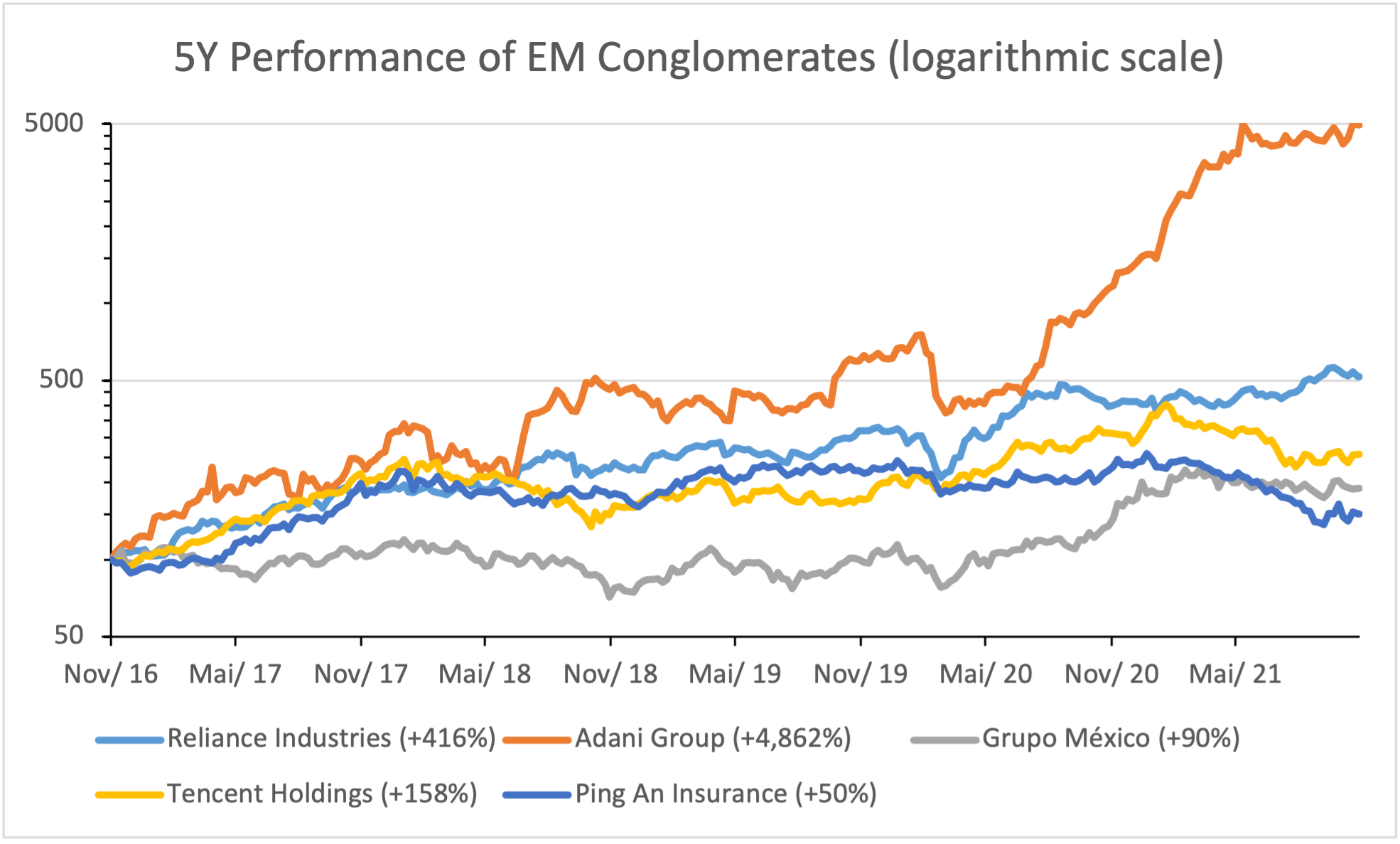

The case of splitting-up conglomerates might not be a worldwide trend, but just a characteristic of companies in developed countries, that are unable to change under pressure of new trends and more flexible competitors. The separations of developed countries-based conglomerates like GE, DuPont, or Toshiba are the result of long periods of slow growth, bad management decisions, and incapacity to allocate funds for the right projects. Once seen as a strength, the huge size of conglomerates, has become a burden in recent years. The conglomerate discount comes from its inability to properly manage various businesses, and the value of the markdown is often as high as 15%. However, in emerging markets like India, China, and Latin America, diversified business groups continue to thrive and expand their activities. Big conglomerate with political connections and an understanding of how to operate in a difficult market can spread its expertise across many industries.

Reliance Industries, the biggest group in India has evolved from being a textiles and polyester company to an integrated player across energy petrochemicals, textiles, natural resources, and telecommunications and operates world-class manufacturing facilities across the country. It is now a world-class conglomerate, operating in far more wider and diverse industries than companies like GE have ever done. Under the management of Mukesh Ambani, The Company is experiencing rapid growth, achieving a net income of $7.7bn in the first 9 months of 2021, a 42% increase from the previous period, reaching a market capitalization of $189bn. Leveraging the economic potential of the Indian market, Reliance Industries is heavily investing in digitalization, through its Digital Services branch: Reliance Jio being the first telecom company outside China to achieve 400 million active users. The company is also the Indian largest producer of petrochemical products, largest B2C retailer and is contributing 5% to India´s GDP. The success story of Reliance Industries shows that conglomerates that operate in traditional industries can thrive, under the guidance of a capable management, with a clear business-strategy in mind.

(Source: Yahoo Finance)

Although industrial conglomerates in developed countries are increasingly splitting up, a new generation of big businesses are growing in the tech world with companies like Google, Amazon, or Ant Group entering every conceivable digital industry and product. Being rebranded as Alphabet in 2015, Google has become a conglomerate, incorporating everything from cloud services, mobile software, hardware devices, fiber networks, and data centers. From a stock price of around $660 in Aug 2015, right before the rebranding, Alphabet has now reached a stock price of $3000, bringing its valuation to $2 trillion. This comes after years of optimizing its advertising-based revenue system, while using its spare-capital to invest in projects with high-growth potential, placing its bets on AI technology, and trying to create a seamlessly ecosystem for its customers. In opposition to heavy conglomerates, Alphabet is a dynamic company, with revenues of more than $200bn, that in the near future will rather engage in an intense M&A process, than doing a split-up

Private equity funds come to resemble old industrial conglomerates, becoming comparable in size with giants like General Electric or Lockheed Martin. One of the best examples is KKR, one of the most renowned funds, with its origins in the early 1980s, which in recent years has become a corporate heavyweight. With more than 280 companies in its portfolio and with a cumulative of 800,000 workers, KKR would be one of the five biggest private sector employers in the US, with more than double the employees of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway conglomerate. With an investment industry worth more than $4tn, KKR and other private equity firms base their success on a decentralized-business model and on placing capable-managers to run the companies.

Conclusion

Through the ever-changing currents of business, some companies emerge as era-defining institutions, very visible in the lives of their customers; while others fail to adapt and are slowly pushed into the pages of history. The trend of industrial conglomerates in the US and Europe splitting up is gradually progressing and will be persistent. The affected companies will be able to stay, albeit in a smaller form with less diversification. However, conglomerates are not disappearing, but their form is evolving. Big tech companies are building up groups similar to conglomerates, claiming that synergies between their businesses exist. Furthermore, private equity funds have developed conglomerate like structures, owning business in various industries. Moreover, also industrial conglomerates will stay for some more time, at least in emerging markets, imitating the history of their former western counterparts.

0 Comments