Introduction

In the ever-evolving world of finance, the wealth management and private banking industries have been subject of change in the past decade, propelling such business units at the forefront of various institutions. In the aftermath of the great financial crisis these divisions played a pivotal role in search for resilience and stability. Emphasized by a low interest rate environment with growing global wealth, the strategic integration of wealth management within investment banks, exemplified by Morgan Stanley’s success, and the strong expansion of Swiss private banks underlines the transformative power of these divisions. With a fall in deal making as per global uncertainty and higher interest rates, wealth management units are taking a larger share of revenues for investment banks and prove their never stronger importance. However, the current macroeconomic environment will also oppose challenges to wealth managers who will need to reshape portfolios and maintain a strong performance to satisfy clients. Furthermore, the fall of Credit Suisse will potentially disrupt the industry as Switzerland some investors’ confidence and status as wealth management and private banking paradise. Let’s dive into these units’ roles, attractive business models, trends in the past decade, and what’s next for the industry.

Overview of the wealth management/private banking industry

Private banking and wealth management are two closely related financial services that focus on catering to affluent clients, such as high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) and ultra-high-net-worth individuals (UHNWIs). While there is often some overlap between the two terms, wealth management and private banking have distinct focuses and areas of emphasis. Within different institutions, they can coexist as separate services, be integrated into a comprehensive offering, or one may be considered a component of the other depending on the structure of the financial institution observed.

As the term suggests, private banking primarily focuses on providing personalised banking services to affluent clients. This includes services such as savings and checking accounts, exclusive banking products, customised loans, and other financial solutions. Fundamentally, private banking encompasses traditional banking services with a higher level of personal attention. While private bankers may offer some financial advisory and planning services, like guiding clients on basic investment strategies, these services are not as comprehensive as in wealth management as the relationship between the private banker and the client is more centred around banking needs. Interest rates on customised credit and lending solutions are personalised to the client’s financial profile. Private bankers actively try to attract the largest clients to increase revenues that are often calculated as a percentage of the client’s assets. Therefore, the larger the client, the larger the revenue. Additionally, when the private banking business is part of a major financial institutions, private bankers also have the responsibility of fundraising from their clients for the various funds that the bank has. Due to the nature of the services provided, private banking is usually regulated as a traditional banking service and is subject to banking regulations.

On the other hand, wealth management offers a set of services that go beyond traditional banking. These include investment advisory, financial, estate and tax planning. The goal is to provide a comprehensive approach to managing the client’s financial life. Investment management is the core service, and it aims to optimise the client’s investment portfolio to achieve specific financial goals through various investment vehicles, from traditional assets to alternative investments. Unlike private banking, wealth management takes a more holistic approach, as the relationship with the client is an ongoing collaboration to manage various aspects of the client’s wealth. In fact, wealth managers do not only provide personalised investment advice based on the client’s financial goals, risk tolerance and time horizon, but they also provide support in optimising tax efficiency, transferring wealth to heirs, and adjusting the financial plan over the years. Large financial institutions typically offer wealth management services, but there are also specialised independent wealth management firms. As already mentioned, in some financial institutions private banking and wealth management are integrated into a comprehensive offering. In this situation private bankers often work with wealth managers to pitch some of the bank’s funds and products to clients to further expand their revenue stream.

Although the services differ slightly, private banking and wealth management operate similarly: building long-term relationships with affluent clients and making revenue through fee-based and commission-based structures. These vary among institutions, and the choice of fee model depends on the range of services provided, the level of customisation and the costs incurred by the financial institution. Most firms charge asset management fees typically calculated annually and are a percentage of the client’s portfolio value. On top of these fees, they may also charge performance fees and one-time fees related to specific transactions. Private banks also earn revenue on interest rate spreads on loans and commissions from selling financial products. Several aspects of their business models make private banking and wealth management attractive sectors. Firstly, even though the fees are small, the margins they earn are considerably high since they only cater to high-net-worth individuals. Furthermore, wealthy clients seek long-term relationships with their financial advisors, leading to stable and recurring revenues for the financial institutions. The ability to retain clients over an extended period allows to build a revenue stream that is more reliable compared to other businesses carried out by the same large financial institutions. Finally, private bankers and wealth managers offer a wide range of financial services and being flexible in the services they provide to clients creates additional revenue streams and diversification.

As mentioned above, private banking and wealth management services typically cater to affluent individuals and families, such as high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) and ultra-high-net-worth individuals (UHNWIs). A high-net-worth individual is an individual with a minimum net worth of $1m in highly liquid assets, such as cash and investible assets, while a very high net-worth individual has at least $5m. Lastly, ultra-high-net-worth individuals are those who have a net worth of at least $30m in investible assets net of liabilities. Some private banks might also provide services to selected mass affluent individuals with between $100k and $1m in liquid financial assets plus an annual income exceeding $75k. It is important to acknowledge that this classification may vary across financial institutions and countries, and they are not set-in-stone figures but more general guidelines. Wealth management services may be also used by institutional clients like pension funds, endowments, foundations, and insurance companies. The services and strategies differ from those provided to individual clients, but the focus remains on optimising financial assets. Despite having different needs, all these clients seek wealth management services to receive advice on strategies and solutions that are personalised to their specific needs and profiles.

The central hub for private banking and wealth management in the US is New York, while in Asia, Singapore and Hong Kong have become the major hubs. Europe counts several locations with a high concentration of wealth management and private banking firms, such as London, Frankfurt and Luxemburg, but the primary hub is Switzerland. Cities like Zurich, Geneva and Basel house many renowned private banks and wealth management firms. As of 2022, Switzerland had a significant concentration of high-net-worth and mass-affluent individuals, accounting for more than 95% of the Swiss population, one of the highest percentages globally. Furthermore, individuals from other countries hold their wealth offshore in the Swiss wealth management market due to tax efficiency, local political and economic stability, better returns, and a diverse investment product range. Not surprisingly, UBS, headquartered in Zurich and with $3.9tn in total assets under management, consistently ranks among the world’s largest private banks. Other major global banks, such as JP Morgan ($2.4tn), Goldman Sachs ($2.5tn), HSBC ($3.0tn), Bank of America ($1.4tn), Morgan Stanley ($1.3tn), and Citigroup ($2.4tn), also operate successfully in the private banking and wealth management businesses together with Swiss-based firm Julius Baer Group with $459bn in AUM and US-based Charles Schwab Corporation with $7.1tn.

Wealth management and private banking services are supported by a series of professionals whose goal is to satisfy clients’ expectations and foster long-term relationships. For these businesses, collaboration and a multidisciplinary approach are necessary as the needs of the clients are diverse and complex. The roles within the businesses can be divided into two macro-categories: client relations and investment functions. The relationship manager/private banker is the point of contact between the client and the financial institution. This position involves understanding the client’s financial goals and needs, providing personalized advice, and pitching the funds that the wealth manager proposes. This role is crucial as the business model is based on recurring revenues from long-term client relationships. The other key component of wealth management services is the investment function. Portfolio managers work with their teams to set up funds and make investment decisions for the clients. They effectively manage the clients’ assets and monitor market trends to adapt the portfolios accordingly. This capability within wealth management and private banking is crucial because clients choose where to invest their assets based on performance indicators. Therefore, the bank would not achieve large and reliable revenue streams without a strong investment team. Finally, it is important to mention other roles within wealth management that provide personalized advice to clients: risk and compliance officers, tax and credit specialists, and legal advisors.

Trends in the last decade

In the decade following the global financial crisis, the wealth management industry was at the core of a very long period of market growth and economic stability. This was largely due to a sharp rise in global markets, which grew at an average annual rate of 14% between 2012 and 2021. As a matter of fact, the performance of capital markets accounted for 70% of industry-wide asset growth meaning that, in many cases, asset value did not reflect the efficiency of the investment strategies. Moreover, 2021 can be considered the last year of remarkable economic performance and reach: client assets rose $7.9tn to a total record of $50tn worldwide, in part due to a strong market rebound after the COVID-19 pandemic. With the rise in wealth, profits subsequently rose to an all-time high of $58bn for the industry in the same year, with margins reaching 24%.

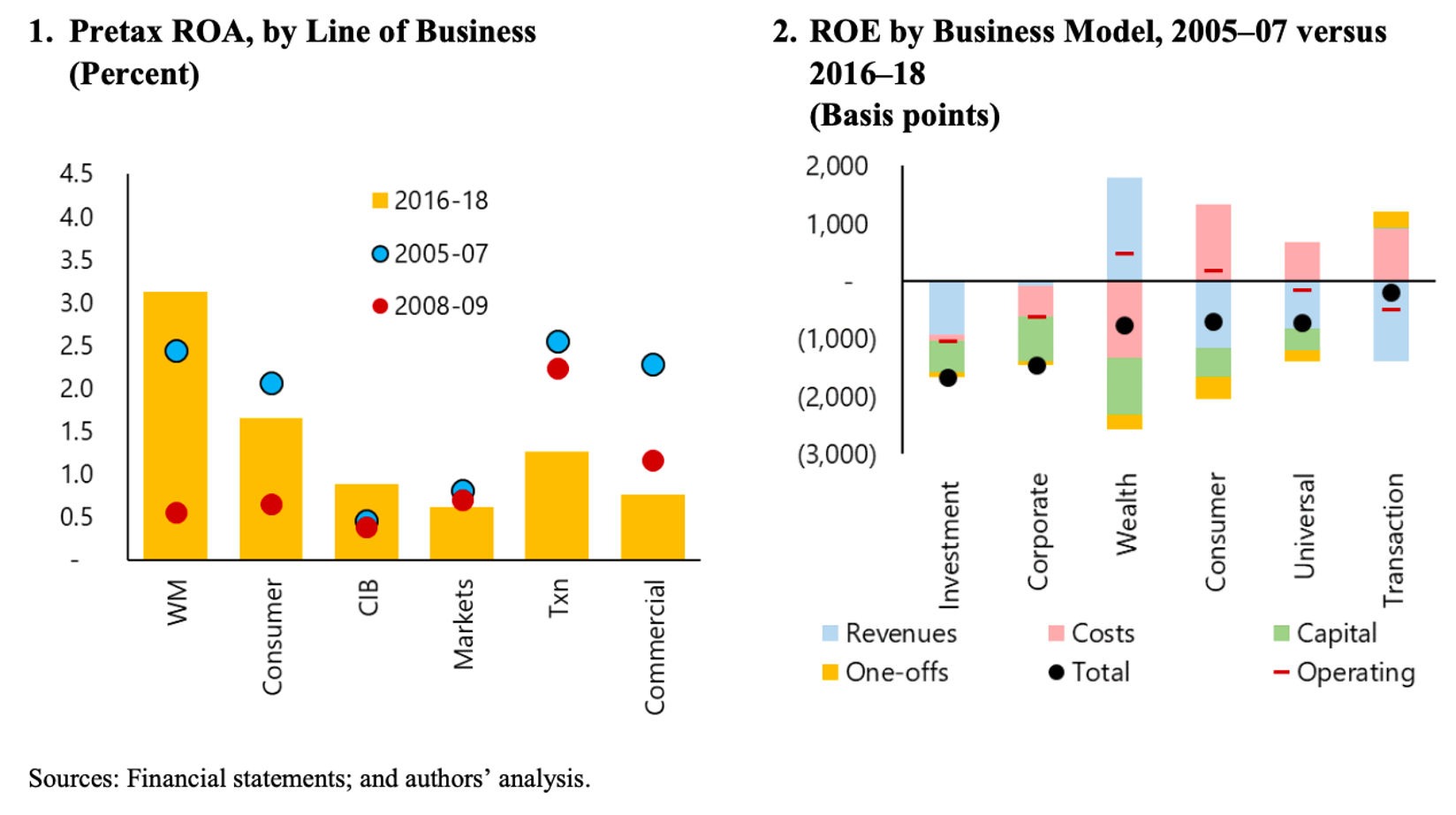

Even though wealth management has become more relevant now, the picture was different before the great financial crisis. It was only then, when profitability dynamics from other divisions were reshaped, that banks had to make substantial adjustments in their business models. They had to take into account several profitability measures, including leverage ratios, calculated by dividing the bank’s Tier 1 capital by its total consolidated assets, to better align banks’ capital against their risk exposures. From the graph below on the profitability dynamics by line of business, we notice that the most pressured firms were those whose strategy was notably focused on corporate banking and markets activities.

Profitability Dynamics by Business Model and by Line of Business

Source: Post-Crisis Changes in Global Bank Business Models: A New Taxonomy; by Caparusso, Chen, Dattels, Goel, Hiebert.

Thus, in search for stability and diversified revenue sources, many firms investigated wealth management, either with a shift in their business model or through acquisitions. For example, Merrill (officially Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith Incorporated), made significant losses due to the drop in the value of its CDOs in 2008. Trading partners lost confidence in the firm, pushing it to its sale. In September of 2008, the day before Lehman Brothers failed, Bank of America [NYSE: BAC] announced and closed their acquisition of Merrill at a 70% premium, under alleged pressure from federal officials. After merging Merrill into its business, Bank of America continued to operate it for its wealth management services, integrating its investment banking unit into the newly formed BofA securities. For the following years after the crisis, the wealth and investment management division of the bank proved to be profitable more than most of the other segments and, after Merrill recovered from its losses during the crisis, it continued to grow, reaching 28% increases in revenue from Q4 2021 to Q1 2022.

In other cases, giant banking groups sought to refocus their business. UBS [SWX: UBSG] is an example of this phenomenon. In pre-crisis years, its investment banking unit contributed a little less than half of the bank’s before-tax profit and revenue, but it became the source of large losses during the crisis, primarily due to its position on US real estate and other credit positions. UBS was stabilized by a package of measures given by the Swiss Confederation and the Swiss National Bank in late 2008. Since then, the bank has shifted away from investment banking activities towards its other existing businesses, specifically global wealth management and Swiss retail and corporate banking. Then, it repositioned its investment bank to a more client-centric model in 2009. By 2010, the Swiss giant had halved its balance sheet, with the downsizing of their investment banking unit accounting for most of its decline. The group continued its transformation all the way to the end of 2014, progressively diminishing the role of investment banking, exiting a substantial number of fixed-income business lines, in particular complex and capital-intensive credit and interest rate products.

UBS balance sheet and profit

Source: bis.org

As mentioned earlier, another factor that contributed to the growth of wealth management was the substantial increase in global wealth, pushed by a decade of low interest rates. Indeed, most traditional assets greatly appreciated between 2010 and 2014 thanks to worldwide expansionary monetary policies. Lately, growth has stabilized globally across regions. In 2020, assets grew 12% in North America, 10% in Europe, 11% in the Asia-Pacific region, and 12% in Middle East and Africa.

Consequently, banks who bet early on the success of their wealth management divisions are seeing the payoff. Morgan Stanley [NYSE: MS], which opted for the wealth management industry as a more durable source of income a decade ago, saw a yearly pre-tax profit of $6.6bn in 2022, and $24.4bn in revenues of which 45% came from the wealth management unit, highlighting its never stronger relevance. The increase in net new assets (NNA) was $311bn, pushing total wealth-related assets to $4.2tn. The bank aims to generate $1tn in NNA every three years and to reach $10tn in client assets. The division has become so important that the chief of wealth management and co-president Andy Saperstein participated in the “succession race” for the role of the group CEO, a race recently concluded with the win by co-president Ted Pick. Even though Pick was seen as most likely to succeed Gorman, due to his role overseeing the more complex institutional securities business, Saperstein’s prospects were bright, mostly due to the expansion of his division through an aggressive M&A activity.

Another sign of the expansion of the wealth management business is the growth of private banks, primarily in Switzerland. Julius Baer [SWX: BAER], a private banking Swiss corporation, saw its assets under management (AuM) rise 3% year-on-year to CHF435bn ($491.5 billion), and over 270% since CHF159bn in 2008. The increase in AuM is mainly driven by continued net new money inflows and a net positive global equity market performance, only partly offset by a year-to-date currency strengthening against most major currencies. Similarly, the Pictet Group, a Swiss multinational private bank, has reported strong growth in its profit and AuM (CHF638bn in 2023), coming from both positive market developments and net inflows of over CHF29bn in 2021. Operating income increased 33% from 2020 to 2021, to CHF924m. Not only is the expansion financial, but it is also geographical. In 2020, Pictet set up a wholly owned Shanghai arm to tap the evolving fund market in China, while in 2021 the firm struck an agreement with Bangkok Bank to provide wealth management services for the bank’s wealth clients in Thailand.

As a whole, wealth management units have proven increasingly essential to investment banks in search of resilient business, especially in times when deal-making slows down and the need for more stable revenue arises. An example of this case is Lazard Ltd. The firm is divided into financial advisory, which includes the M&A and Capital Markets divisions, and asset management, which comprises its wealth management business. In Q3 2023, the revenue from the financial advisory unit, which has long been the biggest of Lazard’s two main segments, fell below the asset management unit’s revenue for the first time since Q1 2021. Specifically, the revenue from financial advisory fell 42% to $261mn in Q3, while asset management’s was almost flat at $262mn, compared to last year.

What’s next?

Although the growth of the wealth management industry has proven essential in boosting banks’ profits and in alleviating the downturns in dealmaking, the business is no stranger to market volatility or victim of the new tighter worldwide monetary policy. Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs [NYSE: GS], JP Morgan [NYSE: JPM] and Citigroup [NYSE: C] have lost a combined $962bn in private banking assets over the course of 2022, due to low client activity and declining equity and bond markets. Morgan Stanley alone saw $802bn leaving the division compared with Q4 2021. According to Jane Fraser, CEO of Citi, wealth management suffered from the macroeconomic environment, which created difficulties for investment fees and assets under management, especially in Asia. Denis Coleman, chief financial officer of Goldman Sachs, attributed the fall in revenue for both asset management and wealth management (whose revenue is posted together) to steep declines in equity and debt investments.

Increasing interest rates require careful attention when crafting an investment portfolio, as they can take some opportunities away from investors, as well as provide them with new ones. Commercial real estate investors are probably going to deal with higher costs, due to the combination of rising interest rates and post Covid-19 work culture. In other cases, banks are reporting increased interest rate revenue and fee due to this economic environment. Wells Fargo’s wealth and investment management group, which includes roughly 12,000 financial advisors, saw net interest income rise to $1bn in Q3 2023, a 10% increase compared to Q2 2022. This was due to the bank’s balance sheet composition and it highlights the importance of predicting or adjusting portfolios according to the interest rates in the market. Over the same quarter, noninterest income fell by 5% to $2.64bn, but the bank still managed to beat analysts’ estimate of $1.10 earnings per share, at $1.25. At Wells Fargo [NYSE: WFC], the wealth management group made up roughly 18% of total revenue for the quarter of $20.5bn.

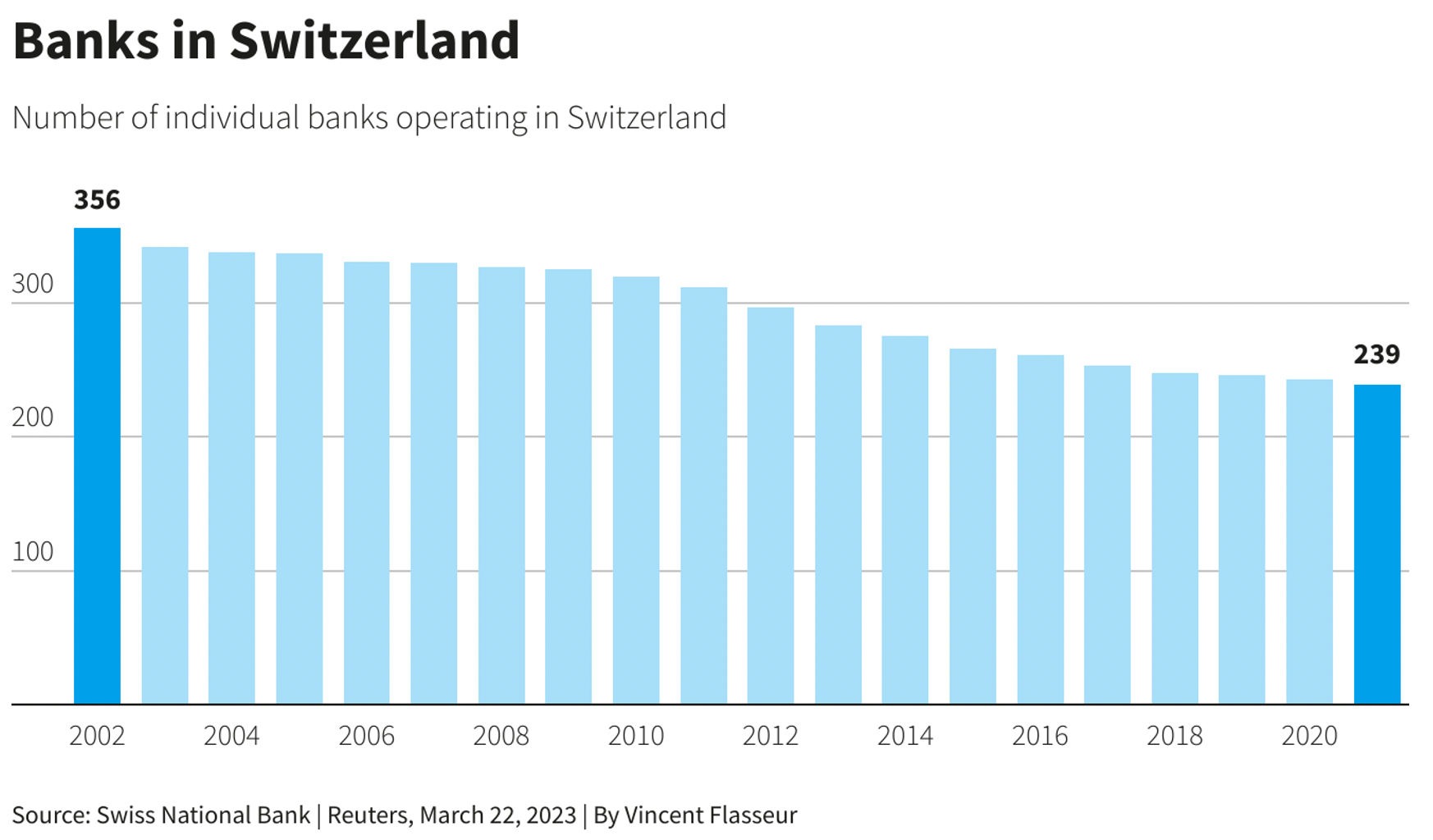

However, 2023 was characterized by both higher interest rates and the fall of Credit Suisse, one of the most famous wealth managers in the world with CHF540bn. The emergency takeover of the Swiss giant by rival UBS will have two major consequences in the medium term. The first is that, given this forced consolidation, smaller and newer private banks could potentially secure themselves a bigger slice of the pie. The other one is that the intervention of Swiss regulators and the controversy around the decision to wipe out Credit Suisse’s AT1 bonds has left investors skeptical of the future of Switzerland as a private banking paradise. According to a 2021 Deloitte study, Switzerland manages $2.6tn in international assets, making it the world’s largest financial center, ahead of both Britain and the US, but its image has clearly been fragilized by the fall of its second largest bank which raises doubts for the future.

However, it faces pressure from centers such as Luxemburg and, particularly, Singapore. When holders of Credit Suisse AT1 bonds got nothing, while shareholders, who usually rank below bondholders in compensation terms, received $3.23bn, Switzerland lost some of its credibility as a stable and predictable country. The government invoked emergency legislation, allowing a public liquidity backstop, not yet part of Swiss law, providing up to CHF100bn liquidity to Credit Suisse. However, perhaps more controversial was the fact that the emergency law allowed the takeover to happen without shareholder approval.

The Swiss Bankers Association presented the rescue as a sign of strength, but Switzerland’s outsized banking sector has been under pressure for years as other countries attempt to stop tax evasion and banking secrecy declines. Similarly, while in countries like the UK senior managers can face criminal sanctions, Switzerland does not have many mechanisms to hold top bankers individually accountable for mismanagement. Moreover, the financial sector’s contribution to the Swiss economy has fallen from 9,9% in 2002 to 8.9% of Swiss GDP in 2022, with industries like pharmaceuticals gaining importance.

While Switzerland’s long banking tradition and structural advantages point to its heavy involvement in banking in the future, the competition is fierce, and centers such as Singapore will most likely become more relevant than now in the future of wealth management.

Conclusion

In conclusion, wealth management units have proven their resilience and evolution in the past decade: from being a crucial part of investment banks’ recovery after the great financial crisis to becoming indispensable components as stable revenue sources in times of slow deal making. However, the current macroenvironment also represents a challenge for wealth managers who are forced to quickly reshape portfolios and maintain strong performances to attract new clients. Furthermore, the industry faces a potential disruption with Switzerland, the largest wealth management hub, being forced regain investors’ confidence in order to keep its leading position and attract the world’s wealthy. Nonetheless, in navigating this complicated environment, one thing is sure: the best-in-class institutions are poised to shine and establish themselves as clear industry leaders, leveraging their expertise to ensure robust returns for their clients.

0 Comments