Introduction

In November, amidst concerns of a slowdown in the Chinese economy, investors found a glimmer of hope with China’s new finance minister announcing increased budget spending to support the post-pandemic recovery. However, this optimism is now overshadowed by a significant challenge as Zhongzhi, a major player in China’s extensive shadow financing market with a shortfall of up to $36.4 billion, recently declared itself “severely insolvent.”

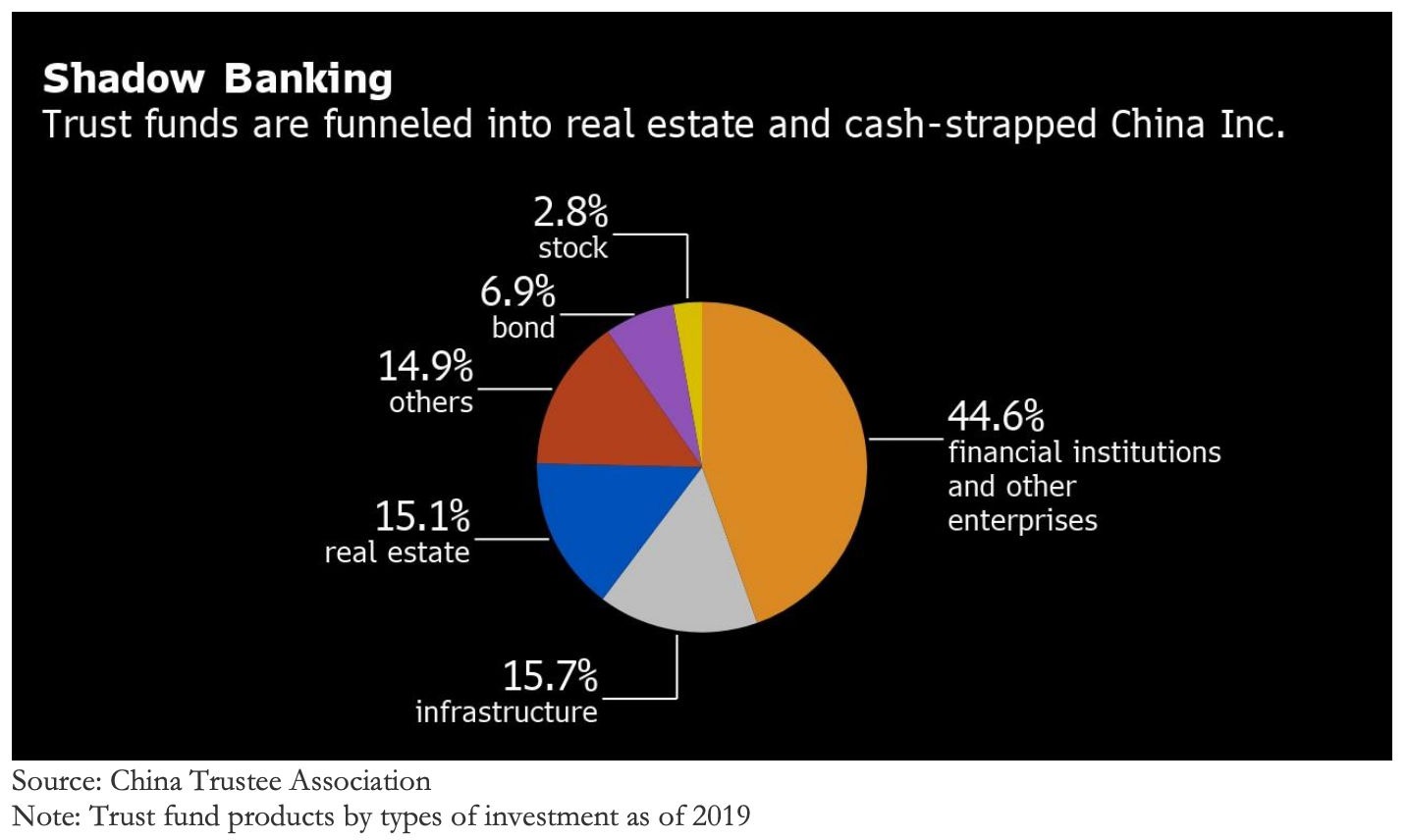

Zhongzhi, part of China’s nearly $3 trillion shadow financing market, operates by organizing capital from companies and individuals at higher rates than traditional banks. The firm, heavily tied to the real estate sector, is both a direct investor in property and a lender to developers through intermediaries. The insolvency of Zhongzhi exacerbates the repercussions of China’s property sector slowdown, contributing to a worsening liquidity crisis.

While Zhongzhi blames the shortfall on the recent death of its founder and the lack of proper management in the company thereafter, its insolvency raises more systematic concerns for China’s shadow financing industry and its intricate relationship with the real estate sector. This development follows the news about the troubles at two of the major players in the Chinese property sector, Country Garden [HKG: 2007] and Evergrande [HKG: 3333], signalling potential repercussions for commercial banks if the economic downturn persists.

Retail investors at Zhongzhi expressed discontent over missed payments, seeking to file complaints with Beijing authorities. However, a government bailout seems unlikely as Beijing is grappling with a two-decade high budget deficit of 3.8%. With tax revenue pressures and reluctance to increase leverage, the potential stimulus may not be sufficient to break the cycle of debt defaults and liquidity constraints between the shadow banking industry and real estate.

The failure of the Chinese property sector – a matter of if or when?

For decades, the real estate sector fueled China’s economic growth, serving as a job creator and a wealth store for the middle class. However, its expansion through substantial debt, surpassing project values, led to a reliance on the assumption that property prices would consistently rise. To curb speculative practices and prevent a housing bubble, the government introduced the Three Red Lines Policy in August 2020. This policy, aimed at reducing developer leverage, had severe consequences for major real estate companies like Evergrande and Country Garden.

Evergrande had expanded aggressively by borrowing more than $300bn. The new measures led Evergrande to offer its properties at major discounts to ensure money was coming in to keep the business afloat. It eventually started struggling to meet interest payments on its debt obligations and saw its shares lose 99% of their value in the past three years. Evergrande since then has been working with creditors to renegotiate its agreements and eventually filed for Chapter 15 bankruptcy protection in a New York court mid-August 2023 to be able to protect its U.S. assets during negotiations with its creditors.

Following suit, Country Garden, reporting a $7.6 billion loss for H1 2023, warned of a potential debt default. This came as a shock as this was China’s largest developer by contracted sales from 2017 to 2022. It focuses its operations on smaller cities, whose fast expansion came with the price of higher exposure to economic downturn and the housing slump. While Evergrande’s debt surpasses $300bn, liabilities on Country Garden’s balance sheet amount to $187bn. However, the latter currently has over 3000 pending projects, which is the reason why experts worry that its collapse might have a greater impact than Evergrande’s default in 2021. The ongoing real estate crisis puts immense pressure on China’s banking system, with nearly 40% of all bank loans linked to property. As dozens of developers default, concerns rise about the potential need for the government to bail out banks, a scenario met with tepid enthusiasm from the national government.

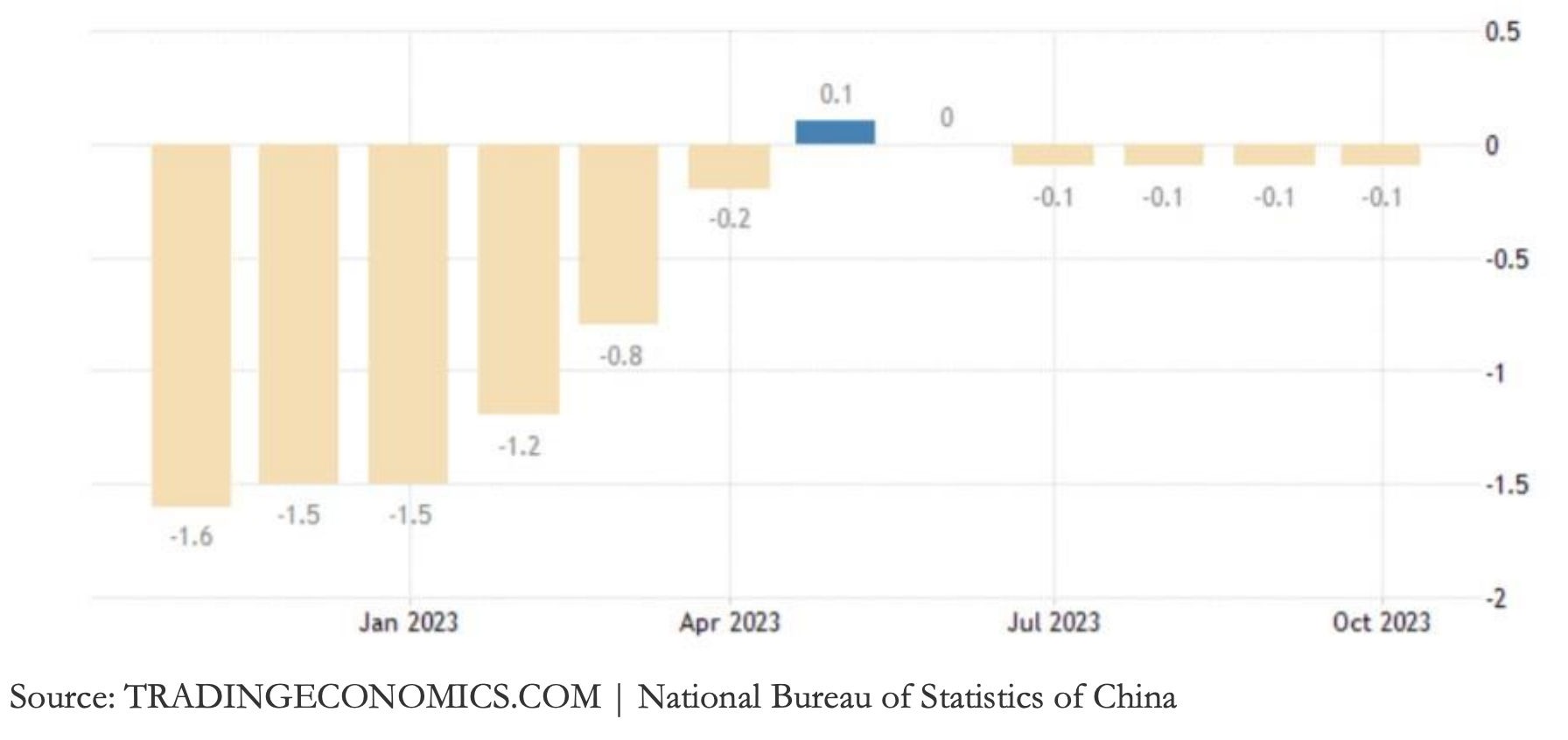

Recent data shows a 0.1% year-on-year drop in China’s new home prices in October 2023, marking the fourth consecutive month of decline. Despite Beijing’s efforts to reverse the property slump, the real estate sector’s challenges persist, raising questions about how the government will address weakening economic growth, escalating local government debt, record-high youth unemployment, and the shadow banking industry’s downfall.

The Rise of Shadow Banking

Shadow banks, also known as non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs), differ from traditional banks by operating with little to no regulatory scrutiny. These are financial intermediaries that create credit with no government oversight. In China, rapid growth of the shadow banking industry came when the country’s economy faced a credit crunch – in the years following the Great Financial Crisis. Traditional banks could not meet the demand for funding due to tight regulation on lending. Estimates show that between 2010 and 2012, China’s shadow banks grew at a rate of 34% per year. More recently, the low interest rate environment that followed the Covid-19 crisis led to struggles in generating attractive returns on investments. In turn, investors have increasingly chosen shadow banks as these often offer higher returns. Additionally, the rise of online lending and fintech has allowed for easier access to financing for those who may not qualify for traditional bank loans.

The situation in China is drastic. For the lending to developers from four biggest local traditional banks, Bank of China, Agricultural Bank of China, China Construction Bank and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, the prevalence of non-performing loans is expected to be as high as 15%. On the other hand, the shadow bank sector in China is estimated to be $3tn loan industry. The Reserve Bank of Australia suggests an even higher figure – around 40% of China’s $17.7tn GDP. Last year, Beijing restrained shadow banks’ predatory lending practices. Some shadow banks have already failed as a result, including one of China’s oldest – Xinhua Trust.

Tying It Together

The struggling real estate companies that have notoriously turned to shadow banks for financing had kept their debt off the books. Some of the hidden debt was provided by trust companies that make up the shadow banking system. As of March 2023, 7.4% of Chinese trust funds’ value was exposed to real estate, amounting to $159bn. However, the actual level of developers’ borrowing is estimated to be more than three times greater, as per data cited by Nomura. In May 2023, one of China’s oldest shadow banks – Xinhua Trust – has declared bankruptcy. The severely insolvent Zhongzhi, a major Chinese shadow bank, recently declared its shortfall of $36.4bn and is now under criminal investigation. These events are alarming for the whole world, not just China. If the $3tn Chinese shadow banking industry would begin to fail, the ripple effects would be felt globally. Since a lot of Chinese consumers invest in the shadow banking industry due to its attractive rates, a collapse in the sector will affect millions. In turn, it is anticipated that Chinese consumption will be hit across the board. The slowdown of China’s economy, which has been an engine of global economic growth for well over a decade now, will impact most, if not all, countries’ economies. In addition, while it is hard to assess where the Chinese shadow banks invested or borrowed across the globe, the defaults in the sector will have implications on global lenders and institutions.

Future outlook

Analysts at JPMorgan warned of a vicious cycle in Chinese real estate financing, with both non-bank creditors and property developers in a persistent liquidity crunch. Companies like Country Garden continue to operate with high leverage and have created oversupply in the fast-growing real estate sector, forcing them to sell at discounts, with prices already falling. This is likely to cause yet another wave of defaults for Chinese property developers, with around a dozen having failed already.

If this persists within the shadow banking sector, authorities in China will likely further crack down on shadow banks, despite already limiting their ability to finance property. The property bubble will still probably burst in China, but with more severe regulation for non-banks and with bailouts for the larger banks, the country might manage to see this crisis out; not without consequences tough, as this is likely to spur a recession in China, while also signalling a severe slowdown in the country’s economy, after two decades of impressive growth.

0 Comments