Introduction

Over the past ten years, Germany has always been the leading European country in terms of economic growth. Notwithstanding a series of emergencies arising from Southern Europe, such as the Greek government-debt crisis and the Italian political instability, the federation was able to deliver an impressive economic performance, corroborated by a sky-high current account surplus, a record-low unemployment rate, and an almost uninterrupted GDP growth pattern. However, the US-China trade war, Brexit, and weakening global economic conditions have recently weighed on the German economy, which is now on the brink of a recession. Consequently, the subject of the debate on Germany has shifted towards fiscal policy, which, in the country, is constrained by a few self-imposed budget balance rules.

In this article, we first try to draw a picture of the current state of the economy in Germany, analysing the most relevant related indicators and hinting at the possible explanations for such disappointing results. With an understanding of what is happening in the country, we then seek to provide an overview of the fiscal rules that limit the extent of Germany’s fiscal expansion, and we explore the possibility of overcoming such rules. Lastly, we present our opinion on the future trajectory of German fiscal policies.

Is Germany Heading Towards a Recession?

A recession is a business cycle contraction of economic activity. There are multiple definitions for an economic recession. In the United States, it is defined as: “a significant decline in economic activity spread across the market, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales”. In the United Kingdom, it is put more straightforwardly as negative GDP growth for two consecutive quarters. In what follows, we will discuss whether Germany is heading towards a recession using the UK definition as well as looking at aspects of the US definition.

First of all, the simplest and most straightforward UK definition. The German GDP growth is measured quarterly. As indicated by the chart below, showing German GDP growth on a quarter to quarter basis, German GDP growth has slowed significantly as a general trend. In the 3rd and 4th quarter of 2018, Germany barely slides past a recession, having negative growth in the 3rd quarter of 2018. The 0.2% increase in GDP in the 4th quarter was revised upwards at a later day and was initially 0.0%. Before the upward revision, this represented the closest result to a technical recession.

Source: Tradingeconomics.com

Figure 1 – German quarterly GDP growth

Looking at the present, the 2nd quarter showed again a negative growth of -0.1%. The 4th quarter results are due to be released in a flash release on the 14th of November, with final results being released on the 22nd of November. Current consensus and forecasts are for a growth rate of -0.2% which, if right, would put Germany in a technical recession.

We now look at the US definition of a recession and Germany’s economy in more detail. Very important to a recession is the unemployment rate. Germany’s unemployment rate is released monthly and, as of today, it is at a 39-year record low of 3.1%, according to data released in September. Unemployment has continuously decreased in previous years.

Source: Tradingeconomics.com

Figure 2 – German unemployment rate

Therefore, from an unemployment point of view, Germany has a very strong labour market which is not pointing towards a recession.

However, when looking at Germany and its unemployment rate, a certain speciality, called “Kurzarbeit”, has to be taken into account. This allows employers to reduce the working hours of employees, and adjust the pay accordingly, without having to lay workers off. Therefore, Germany’s unemployment rate is a lagged indicator of the actual health of the labour market. When looking at the amount of “Kurzarbeit” in the chart below, we see that their use has been increasing since mid-2017 and, since the end of 2018, it increased drastically.

Source: Financial Times

Figure 3 – “Kurzabeit”: number of short-time workers

“Kurzarbeit” are primarily used in the industrial sector, a sector in which Germany, as a net exporter, is particularly strong. Germany has a cyclical positive trade balance averaging around €20bn a month, constantly followed by a month at around €17bn. Exceptions include the end of 2018. This is seen below in the chart outlining the trade surplus every month.

Source: Tradingeconomics.com

Figure 4 – Trade surplus monthly

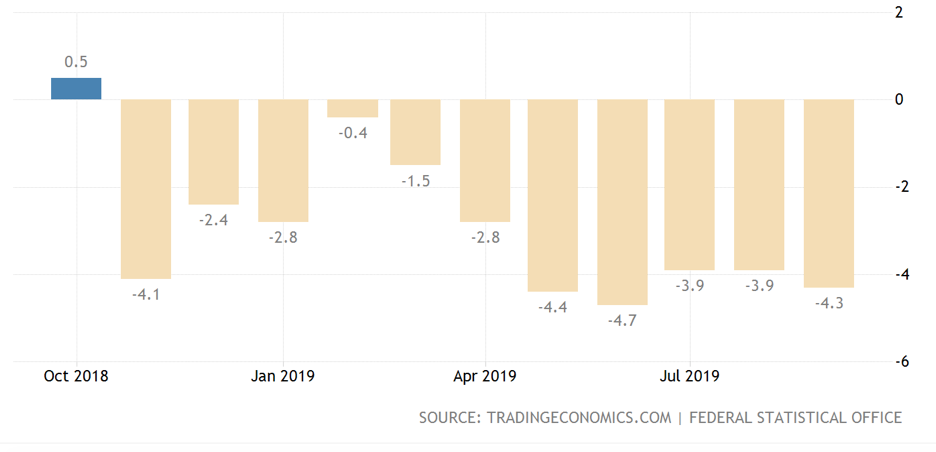

Despite trade uncertainty from the US-China trade war, as well as an uncertain Brexit outcome, has taken a toll on Germany’s industrial production, in 2019 industrial production has continuously decreased, with a negative peak of -4.7% in one month alone. This partially explains the increase in “Kurzarbeit” and, therefore, the fact that Germany’s weak industrial sector has not spilt over into the labour market yet. However, this is only a matter of time since even “Kurzarbeit” have their limits.

Source: Tradingeconomics.com

Figure 5 – German month-on-month industrial production change

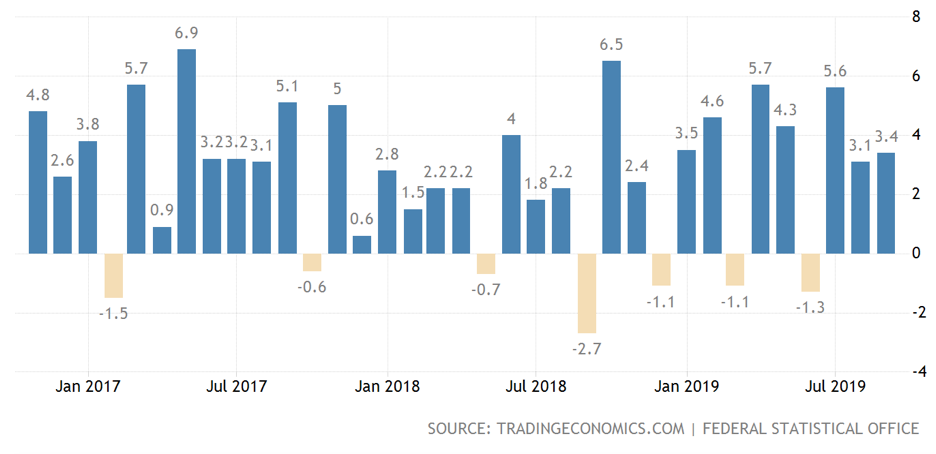

Lastly, let’s take a look at the wholesale-retail sales of Germany measured month on month. This figure shows consumer spending and, therefore, consumer confidence in the economy. Accordingly, it is a vital factor to quickly spot an incoming recession by seeing a drop in consumer spending in retail stores. However, the graph below shows that spending has stayed strong but, still, an increasing frequency in monthly declines indicates a worrying trend which is no alarming signal yet.

Source: Tradingeconomics.com

Figure 6 – German month-on-month wholesale-retail sales

Is Germany in a recession?

From the UK definition of a recession, Germany is not officially in a recession. However, with negative predictions for Germany’s economy in the 3rd quarter, we can assume Germany is highly likely to fall into a technical recession. This is also supported by the US definition of a recession, which has shown a decrease in industrial production and an increasing frequency of a decrease in monthly retail sales. While the labour market has not shown a decline and is holding steady, this can be attributed to the use of “Kurzarbeit”, thus delaying the spillover into the greater labour market. Therefore, we conclude that Germany will enter a technical recession once the official data is released.

Fiscal Rules and Expansionary Measures

As previously analysed, with record-low interest rates and an economy which is heading towards a recession, the straightforward policy response from the German government should be based on a material fiscal stimulus package. Nonetheless, after the financial crisis, Germany gradually implemented two federal schemes devoted to constraining the possibility of running government budget deficits. More specifically, the “Debt Brake” is a constitutional law which limits the federal government’s structural deficit to 0.35% of gross domestic product, while the “Black-Zero” budget is a commitment, made by the German government, to run a balanced budget, thus financing any spending increase with state revenues alone. Various methodologies exist to overcome the effects of such policies but, for their implementation, either a regulatory or a political strategy change are required. Moreover, as we are going to detail later, Germany is rumoured to be considering setting up public independent investment agencies, to boost capital expenditure without falling under the fiscal rules’ provisions.

The Debt Brake

Following a proposal made by the former Minister of Finance Peer Steinbruck, in June 2009 the German parliament approved a legislative package devoted at implementing the federalism reform that Germany started four years before. Among the new rules, which changed the German Basic Law (Germany’s constitution, the so-called “Grundgesetz (GG)”), the most important policy change is represented by the introduction of the “Debt Brake”, a set of constitutional laws whose aim is to limit net borrowings by the Federation and its Lander.

The German government borrowings have been subject to constitutional rules since the foundation of the Federal Republic in 1949 and, prior to the introduction of the Debt Brake, the matter was lastly reformed in 1969, allowing the central government to borrow funds above the ordinary limit set by the total estimated investment expenditure stated in the federal budget. Clearly, in 2009 Germany presented substantially different economic and social conditions with respect to the ones that prevailed at the time of the reform. Also, the combined effect of weak fiscal rules, demographic changes, the German reunification process and the financial crisis contributed to Germany’s failure in meeting the 60% debt-to-GDP ratio set by the Maastricht Treaty. Consequently, as stated at that time by the German federal ministry of finance, “the current crisis in the financial markets further underlines the importance of a state that is fully capable of fiscal policy action at any time. Therefore, the new deficit rule is not only a cornerstone for the present crisis-related “exit strategy” but will also strengthen the resilience against crises in times to come”.

According to the Debt Brake rules, both the Federation and the Lander must balance their budgets without any additional net borrowing. However, under “normal economic conditions” the Federation is allowed to increase its expenditures up to the point in which net borrowings exceed 0.35% of the GDP, while such provision does not exist for Lander. Moreover, in case of natural disasters or exceptional emergencies, the Federation and the Lander may raise additional funds, exceeding the above-mentioned limits, but those amounts have to be repaid according to a binding amortisation schedule. The reform applied for the first time in 2011 and, in order to avoid pro-cyclical adjustments, the government was forced to reduce the structural deficit in equal annual steps until the 0.35% limit was reached in 2016. On top of that, from 2020 the Lander are no longer allowed to miss the 0% fiscal deficit target.

Figure 1 – Structure of the new budget rule –

Figure 1 – Structure of the new budget rule –

Source: German Federal Ministry of Finance, Economics Department

Focusing our attention on the budget rule for the Federation, the extent to which the German government is allowed to finance expenditures in a deficit is the sum of four components. The structural component is represented by the possibility to raise structural net borrowings to 0.35% of GDP per annum. The cyclical component introduces admissible changes in fiscal revenues and expenses due to business cycle fluctuations. Accordingly, the provision explicitly employs the cyclical adjustment procedure applied within the European Union. The balance of financial transactions accounts for transactions involving the simultaneous creation of a financial asset and financial liability, such as privatisations or state-granted loans. Those adjustments removed a major inconsistency between the German legislation and the European Stability Pact. Lastly, the control account is devoted to correcting for ex-post non-compliance with the fiscal rules. More specifically, the account will be debited if, when giving implementation to the budget, the limit on net borrowings is exceeded while, in case the actual net borrowings result to be lower than previously forecasted, the account will be credited.

According to recent estimates, in 2020 Germany may have room to increase its debt by ca. €5 billion, in full compliance with the Debt Brake rules. However, it is arguable that such an amount might not be enough to offset the spillovers of a recession. In case the German government was willing to amend the Debt Brake it would need the back of at least two-thirds of Germany’s MPs, the minimum threshold required to modify the German Basic Law. In our view, given the current difficult equilibrium in the governing coalition and the broad support, among German citizens, for the Debt Brake legislation, such an outcome is very unlikely.

The “Black-Zero” Budget

After the successful implementation of the Debt Brake, the German government went further towards the path of fiscal discipline and introduced the so-called “Black-Zero” (Schwarze Null) budget rule, a commitment to achieve a balanced federal budget made by the ruling coalition.

In 2013, the conservative Christian Democratic (CDU) party, headed by Angela Merkel, the Social Democratic (SPD) party, and the Bavarian Christian Social (CSU) party agreed to form a governing coalition whose legislative action would have been set by a “grand coalition agreement”. One of the striking points of such agreement was the call for a balanced budget to be achieved in 2015. In spite of initial projections, the German government realised its goal of running a federal fiscal surplus in 2014, one year ahead of schedule. Moreover, from that moment onwards, the trajectory of the federal finances has not changed, as evidenced by the 1.7% fiscal surplus-to-GDP reached in 2018 and the consistent delivery on the balanced budget target.

Thanks to the Black-Zero budget rule, over the past five years, Germany delivered an impressive economic growth while, at the same time, substantially lowering its debt-to-GDP ratio, in compliance with the Maastricht Treaty. However, the recent slowdown in the German economy has spurred growing pressure to overcome the Black-Zero approach, to fill the country’s large investment needs. At present, even though there is no legal provision underpinning the Black-Zero budget, the three governing parties do not seem to be ready to run a fiscal deficit and recently declared that the balanced budget approach will be again respected. Also, opposition parties, such as the Free Democrats (FDP) and the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), support the Black Zero rule.

In our view, the extent to which the governing coalition will be willing to ease the self-imposed fiscal rule largely depends on the severity of the upcoming recession. Several German economists, former politicians, and even the BDI, the traditionally-orthodox leading organisation of Germany’s industrial sector, have endorsed an expansionary policy change devoted at financing infrastructural and environmental projects. Nevertheless, without a sharp slowdown in economic activity, the government is not expected to pursue a radical strategic shift on a policy which still benefits from high approval rates among German citizens.

Shadow Budgeting

With a clear understanding of the constitutional and self-imposed budget rules that limit Germany’s net borrowings, it is possible to argue that the odds of a German fiscal expansion are very low and, indeed, such a breakthrough would require either an economic or a political change. Still, growing demands for public investments and the negative interest rates environment are forcing the government to develop creative solutions to increase federal expenditures without discarding the Black-Zero budget approach.

As a result of the above-mentioned process, Germany is now rumoured to be considering setting up a “shadow budget”, an alternative federal account which would not fall into the perimeter of both the Debt Brake laws and the Black-Zero policy. Under such a plan, the central government would create public independent investment agencies, whose primary goal would be financing projects to develop new technology, find solutions to global warming, and modernise Germany’s infrastructure. Those entities could benefit from the all-time low interest rates environment, thus being able to raise debt at a negative cost, and their borrowings would not fall into the federal budget but would instead be taken into account by the EU Stability rules. Therefore, since the European Union allows for a deficit-to-GDP of up to 1% in case of a debt-to-GDP ratio well below the 60% threshold, through the shadow budget approach, Germany might be able to raise up to €35 billion in new debt.

The prospect of obtaining a considerable amount of fresh funds without falling short of the current fiscal rules is appealing and, if the government was to decide in favour of the shadow budget, an interesting compromise between fiscal hawks and doves might be agreed. However, setting up public investment agencies is likely to be seen as an accounting expedient, devoted at bypassing both the Debt Brake and the Black-Zero rules, which will expose the governing coalition to the risk of fierce criticism. Nonetheless, in our view, pursuing a shadow budgeting approach is much easier than obtaining the approval for a constitutional change, as well as than abandoning the self-imposed balanced budget rules, and, consequently, represents the most plausible policy that Germany may apply to offset its current economic slowdown.

Conclusion

As extensively analysed, Germany is facing a trade-off between the need to ease its fiscal stance and the willingness to stick with the balanced budget approach and the Debt Brake legislation. In our view, given the current slowdown in European economic growth and the prospects of an escalating US-China trade war, which are not likely to expire soon, a material increase in German government spending is required. Indeed, a small change in the approach towards fiscal policy has already occurred, as evidenced by the fact that in 2019 there will be a modest fiscal expansion, to be followed by more ambitious plans.

Regardless of the specific tools that may be applied, easing Germany’s fiscal stance could boost the region’s auto industry, restore investors’ confidence, revive economic growth, and curb the German trade surplus, thus strengthening the whole Euro Area. Also, an expansionary fiscal policy is likely to lead to higher Bund yields, as invoked by a large portion of the German establishment, while, at the same time, keeping federal debt at a level which is fully compliant with the Maastricht Treaty.

0 Comments