Introduction

What was once the U.S.’ most valuable start-up just declared bankruptcy. Founded in 2010 by the charismatic entrepreneur Adam Neumann, WeWork aimed to revolutionize the traditional concept of office spaces. However, its meteoric rise was followed by a precipitous fall, marked by a harsh operating environment and a failed IPO attempt that unveiled a series of managerial failures and the start-up’s financial turmoil. In this article, we dive deeper into WeWork’s captivating journey, exploring its business plan, explosive growth, catastrophic IPO attempt, and the subsequent challenges that led to it filing for bankruptcy on the 6th of November 2023.

About WeWork

WeWork [WEWKQ: OTCMKTS] was started by Adam Neumann with a first location in lower Manhattan in 2010. The vision of the company was “to create environments where people and companies come together and do their best work”. A year later, it expanded to San Francisco. In 2014, WeWork expanded outside the US for the first time, by offering their product in London and Israel. By the end of the year, the company had 15000 members in eight cities. The story took a sharp turn in 2017, when SoftBank’s Vision Fund [9984: TYO] invested $4.4bn into WeWork, valuing the company at $20bn. At the time, SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son rationalized the investment: “WeWork is leveraging the latest technologies and its own proprietary data systems to radically transform the way people work.” In the following two years, the coworking space company became the largest private occupier of office space in Manhattan and was valued at record-high $47bn by SoftBank. However, in August 2019, just a few months after the valuation, WeWork had to shelve its initial public offering after the filing provided details about the nature of the money-losing company’s financial details and business plans. Soon after, Adam Neumann stepped down as CEO and the company laid off 2400 employees, 20% of its global headcount. In the four years leading up to the bankruptcy, WeWork was left by another co-founder, exited 40 underperforming locations in the US, and changed multiple times of CEO. Despite coupling financial restructuring attempts – such as reducing debt by $1.5bn and getting $1bn in funding – to a 1-for-40 reverse stock split to avoid the risk of being delisted on the New York Stock Exchange, WeWork filed for bankruptcy on November 6th, 2023.

WeWork was a space-as-a-service business: it offered a simplified membership model that delivered a “premium experience” in place of the complexity of leasing real estate. WeWork’s revenue stream primarily came from memberships and services. Through its different membership plans, WeWork All Access and WeWork Workplace management solution, the company provided access to booking workspaces, conference rooms and private offices all from the members’ mobile phones and flexible spaces to enterprises with the option of a hybrid work experience with online booking and meaningful utilization analytics for optimization, respectively. The memberships did not include service fees such as access to conference rooms, printing, photocopies, set-up fees, phone and IT services, parking and others, which made up the second biggest stream of money for WeWork. The company differentiated itself through the many perks it offered at its locations around the world. It provided glamourous offices with open space and modern design, unlimited coffee, free beers and snacks, lounges and phone booths, combined with outdoor terraces, café areas, exercise rooms, swimming pools, valet parking, mini golf, and others at specific locations. WeWork believed these reinforced employee-first culture and increased engagement and productivity. As of 2023, the company offered more than 700 locations in 39 different countries. The cities where service was provided can be seen on the map below.

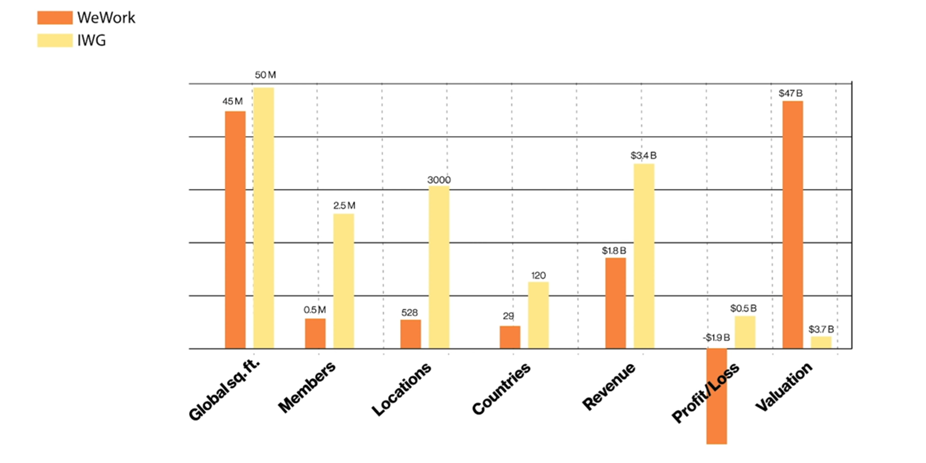

WeWork’s rivals, such as IWG (Regus) [IWG: LON] and the Office Group, offer similar products but differ in more ways than one. IWG, founded in 1989, is the world’s biggest workspace provider and has five times as many properties as WeWork but is focused on a lower-cost basis. To put things into perspective, IWG has five times as many members as WeWork, operates in four times as many countries and generated more revenue, all the while having a lower valuation than the late firm at its peak of $47bn. The Office Group, much smaller than the other giants, offers 50 workspaces in neighbourhoods of the UK and Germany. It grew organically over the span of nearly 20 years and has a very similar model to WeWork, including the benefits of gyms, lounge spaces, meeting rooms and event space hires. It is important to note that WeWork entered the market with little new solutions to offer, and much less experience than its already established competitors.

Figure 2. WeWork and IWG side-by-side. Source: Pitchbook, 2019.

The Takeoff

WeWork’s exponential growth made it the second most valuable private company in the US in 2019. It started with a single location in 2010, grew to 52 in just five years thanks to multiple fundraising rounds, and expanded tenfold between 2015 and 2019. Its growth was fuelled by major investments from SoftBank’s Vision Fund, the first of which valued the company at $20bn in 2017, and totalled $4.4bn. At the time, SoftBank’s CEO saw major potential in the company, including its innovative analytics about the use of the workspace that offered optimal utilization of the offices. In the next 2 years, Softbank made subsequent investments, including the purchase of a warrant to buy up to $3bn worth of shares in the company. At the beginning of 2019, WeWork raised an additional $2bn from SoftBank, which brought the total funding by the bank to over $10bn. The money that was poured into WeWork fuelled its rapid expansion, including purchase and rental of new locations, expansion to new countries and capturing a larger customer base. WeWork was worth more than giants that had been in the industry for decades – the likes of IWG – and its valuation exceeded that of any other coworking space-oriented firm. Despite years of consecutive undisclosed losses in terms of net income, WeWork appeared to thrive in its industry.

WeWork’s first IPO attempt in 2019

To understand why WeWork’s attempt to go public in October 2019 failed, we need to take a closer look at the IPO’s rationale, and the company’s history. The startup was growing extremely fast, attracting more and more investors, including Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase & Co, Benchmark Capital, Fidelity and many others who believed in the ideas of a hyperactive, charismatic, and persuasive founder Adam Neumann. However, The Japanese group Softbank, led by the chief executive Masayoshi Son, did more than any other investor to propel the extraordinary growth of WeWork. Fueled by its more than $10bn of investment, WeWork’s valuation jumped to $47bn in the run-up to its listing attempt in October 2019, making it one of the most highly valued start-ups in the world. But over the years, the relationship between SoftBank and Neumann deteriorated, mostly because of WeWork’s poor financial performance and its founder’s eccentric management style. Towards the end of 2018, after Neumann had demanded SoftBank not to finance any direct rival and the investor’s shares suffered over concerns that it was overexposed to WeWork, Son called of a deal to inject new capital into WeWork. Aware of the company’s need for cash, and instead of cutting costs, Neumann kept opening more properties and acquiring more start-ups, spending $2.4bn in the first six months of 2019. He increased internal growth targets even further, aiming at a growth above 100% for a ninth consecutive year. In 2018, WeWork added 252,000 desks, raising expectations for 2020 to 750,000 new desks. There also was enormous pressure on employees: “People were having nervous breakdowns trying to sign new space. We were always aggressive, but we became ridiculously aggressive,” – one employee recalls. Chief Legal Officer Jen Berrent and Chief Financial Officer Artie Minson already knew that an IPO was the only chance to get the cash they needed and save the company. But Neumann and Son did not like the idea of WeWork going public. So Neumann began looking for new investors, and after getting rejected by Apple, Google, Salesforce and Goldman Sachs, he took an offer from JPMorgan, which would give WeWork $6bn in loans – but only if the IPO raised at least $3bn in new equity.

The filing of the IPO, which was made public on August 14th, 2019, left everybody shocked. First and foremost, it unveiled WeWork’s business structure: a so called “UP-C” structure, which offered tax benefits to Neumann and other insiders who payed taxes on any profits at individual income-tax rates, while public shareholders faced a double taxation, since the holding company payed taxes on its income, and then on any dividend distributions. That structure also created different share classes which would give 20 times as many votes per share to Neumann, as to ordinary shareholders. Moreover, the Neumann family would retain control even in case of Adam’s death, with his wife Rebekah — who had been elevated to co-founder and described as her husband’s “strategic thought partner” — holding the right to pick his successor. Seeing this, investors began worrying about the unrestricted control of the founder’s family. Secondly, the filing revealed how WeWork had paid Neumann rent on buildings he personally owned, and bought the trademark to the word “We” from him for $5.9m. In other words, the founder was enriching himself at the company’s expense. Thirdly, investors found the company’s financials even more concerning and realized that the company would not be able to produce real profits with its current business strategy. Location operating expenses for six months ended June 30, 2019 increased twofold compared to YoY metric, resulting in $2.9bn total expenses, $1.4bn loss from operations and $904.7m net loss for the given six-months period. That figures led to negative profitability ratios (ROTA, ROE, ROS) and showed that with its current cost structure, WeWork would not be able to make a profit. Furthermore, net interest income of $470m, cash balance of $2.5bn, total equity deficit of $2.3bn and total liabilities of $24.6bn gave investors a clear view that the company was over leveraged and would not be able to repay its debt any time soon (all figures are given for the six-months period ended June 30 ,2019). Despite the company’s decadent financial situation, Neumann continued making reckless investments, such as opening an elementary school WeGrow in New York, investing in an indoor wave pool company, and buying a private jet for $60m. Overall, the filing revealed how the executives seeked for opportunities to enrich themselves at the expense of the shareholders. The last straw was in mid-September, when the Wall Street Journal published details of Neumann’s in-flight marijuana consumption. It became crystal clear that without serious governance changes, the IPO would fail, which meant the end for WeWork, which only had $2bn of cash left (just enough for two months of operations). That is why Adam Neumann resigned on 24 September saying: “Too much focus has been placed on me”. Two senior WeWork executives, Sebastian Gunningham and Artie Minson were appointed as co-CEOs. They sold Neumann’s $60m private jet, put many WeWork acquisitions up for sale, postponed the IPO indefinitely, closed down WeGrow, and fired thousands of employees – all the while securing themselves multimillion dollar severance packages.

The SoftBank bailout

Advisers concluded that WeWork needed to raise $5bn quickly to continue operations. SoftBank, the largest WeWork’s investor, once again saved the startup by offering $5bn of new debt, buying up to $3bn worth of stock from existing investors and providing $1.5bn in new cash. Son also demanded that Neumann give up his chairmanship and hand his voting rights to the board. To make the offer more attractive, the Japanese group offered him credit to repay a $500m bank facility on which he was in technical default, agreed to a $185m “consulting fee”, and said SoftBank could buy up to $970m of Neumann’s shares. With just two weeks’ cash left, Neumann and WeWork accepted Son’s bailout. Its $8bn valuation was just over a sixth of the $47bn valuation Son and Neumann had agreed on just 10 months earlier. Even after the rescue, WeWork’s financial position was not strong. The company had $50bn of lease obligations it had promised to fulfill, and even publicly acknowledged that the spectacular failure of its IPO plans could scare off new customers and business partners.

The COVID crisis

WeWork lost $3.2bn in 2020 as Covid-19 shut its co-working spaces around the world, but the losses narrowed from $3.5bn in 2019, as the company decreased capital expenditure from $2.2bn in 2019 to just $49m. Occupancy rates across WeWork’s global portfolio fell from 72% at the beginning of 2020 to 47% at the year end. However, new CEO Sandeep Mathrani, a veteran retail real estate executive, managed to improve WeWork financials: the company cut overhead costs by $1.1bn and trimmed $400m in operating expenses, which improved its free cash flow by $1.6bn. By December 2020 the company had exited 106 underperforming or not-yet-opened locations and negotiated more than 100 lease amendments that added up to an estimated $4bn reduction in future lease payments. Additionally, a growing share of WeWork’s memberships – 54% compared to 43% last year – was coming from enterprise companies that have 500 or more employees. These companies sometimes lease whole floors or buildings and are more stable than individual memberships. WeWork also launched some new profitable projects to help small and medium businesses during pandemic, offered more flexible options to tenants in the UK seeking to split work between homes and offices, and provided £15m to subsidize rents for struggling SME. “The pandemic has fundamentally changed the way people work, accelerating the demand for flexible workspace among organizations of all sizes” Julia Sullivan, a spokesperson at WeWork, said. But even though WeWork adjusted and provided some new solutions to its clients, it faced a huge problem concerning the maturity mismatch between its long-term leases and short-term revenues. In fact, the company had signed most of these leases with landlords before the pandemic, when rents were at their highest. However, in 2020, people expected to pay less for office rent, since there was lower demand. Newer locations were also less likely to be fully occupied, since it takes time to fill them with tenants, so they were bringing in less total rent than mature locations did. In other words, for its newer locations, WeWork was paying more than receiving.

The IPO in 2021

The pandemic recovery has since accelerated the demand for flexible workspaces, as more workers shift toward hybrid or permanent remote work. In March 2021, WeWork agreed to a $9 billion SPAC (special purpose acquisition company) merger with BowX Acquisition. As part of the deal, SoftBank retained a majority stake in the company but agreed to a one-year lock-up on their shares. In May, the Financial Times reported that WeWork’s losses were deepening even as it made preparations for the merger with BowX. WeWork lost $2.1bn in the first quarter of the year, which included a $500m non-cash settlement with Neumann. However, the deal was finalised on October 20, when the shareholders of BowX Acquisition voted in favor of its transaction with WeWork, enabling the shared office space provider to trade on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker WE. On October 21, the company finally went public with shares rising 13% by the end of the day to $11.38, implying a valuation of $9bn, five times less than its initial valuation in 2019. WeWork received $1.3bn in cash from its deal with BowX Acquisition, which included money held in the SPAC trust from BowX’s IPO, as well as a $150m investment from Cushman & Wakefield that acted as a backstop to shareholder redemptions. Investors such as Starwood Capital Group, Insight Partners and BlackRock additionally committed $800m through a private investment in public equity. SoftBank, provided WeWork with a $550m senior secured note and Adam Neumann retained 11% shareholding though he could not sell shares for nine months.

Management failures

Regardless, the company kept making losses and was behind on its own 2021 revenue projections. It’s only by the end of 2022 that WeWork finally showed positive real adjusted EBITDA, but by then its cash balance had withered from $924m to $287m. In 2023 the company completed a balance sheet restructuring to reduce its net financial debt balance by $1.5bn and push out approaching maturities to 2027, a deal that quickly proved to be insufficient. WeWork’s market capitalisation fell to just $40m and the company’s shares and bonds prices were deeply distressed. The business model of Blitzscaling once again has proven to be inefficient in the high interest rate environment. But let us go back to a time when Adam Neumann was a CEO and have a closer look at the management failures.

First of all, Adam Neumann’s chaotic approach to management definitely was a problem. One day he said that WeWork must lay off 70 people, the other day threw a party with thousand dollars expenditures, which did not coincide with his own claim to be “elevating the world’s consciousness”. Moreover, unreasonably high expenses on meditation rooms, pool tables, vegan food stalls and aroma of small-batch coffees gave a rise to a lot of questions. And of course, Neumann’s cases with drugs and alcohol worsened his reputation.

Secondly, S1 filing before the attempt to go public in 2019 revealed some of Neumann’s unjustified huge investments, such as opening an elementary school WeGrow in New York and making his wife a founder and CEO there, investing in an indoor wave pool company and buying a private jet for $60m. Moreover, he collected rent from WeWork on properties that he owned himself and sold the trademark for the word “We” to WeWork for $5.9bn. That has showed how the executives tried to enrich themselves at the expense of the shareholders. Here, a reasonable question arises: what was the Board of Directors doing?

On the 30th of June 2019, in addition to Adam Neumann, WeWork’s board of directors included six non-employee directors, designated by major shareholders: Bruce Dunlevie was designated to serve on the board of directors by Benchmark, John Zhao by Hony Capital, and Ron Fisher by Softbank Vision Fund L.P., which created a conflict of interest. Directors could not say anything bad about the financial performance of WeWork as it would lead to a decrease in the share prices of the large investors that had appointed them. Furthermore, the board was not well diversified as there were no women, and all directors were in the age between 56 and 73, coming from similar professional backgrounds which may have resulted in lack of different opinion. Finally, the business structure gave Neumann 20 times as many votes per share as to ordinary shareholders and unrestricted control to his family, which meant that the board was basically not deciding anything.

To sum up, management failure, an inflexible cost structure, COVID restrictions and post-pandemic high interest rates environment were the major factors at play in the downfall of WeWork.

What’s next for WeWork?

WeWork, which has listed $15 billion in assets, will continue operating as it works to raise financing. Already more than 90 per cent of its lenders have agreed to a restructuring plan, which should wipe out $3bn of debt. The company said it would also file for bankruptcy in Canada, but stressed that its operations outside North America would remain unaffected.

A main takeaway from the WeWork story is that one should always be careful with who he is doing business. Some of the landlords may be happy to terminate their agreement with WeWork to lock in higher rents, but others may not be as fortunate. Regardless, the information they needed to make informed decisions was clearly outlined in WeWork’s financial statement.

In conclusion, the WeWork story is one that was poised to end: managerial failures and excessive backing from few investors made the company simply too risky.

0 Comments