Introduction

The music industry’s evolution, from vinyl to streaming, has not only transformed how we consume music but also revolutionized investment opportunities. With streaming platforms dominating revenue streams and artists navigating the complexities of selling their rights, investors are increasingly drawn to the potential of music royalties as an alternative asset class. Firms like Hipgnosis Songs Fund and BlackRock’s Alignment Artist Capital are capitalizing on this trend, recognizing the stable returns and diversification offered by music ownership. Despite challenges posed by rising interest rates, the allure of music royalties persists, presenting investors with an enticing opportunity to harmonize their portfolios with the ever-evolving rhythms of the music industry.

Trends in Music Industry

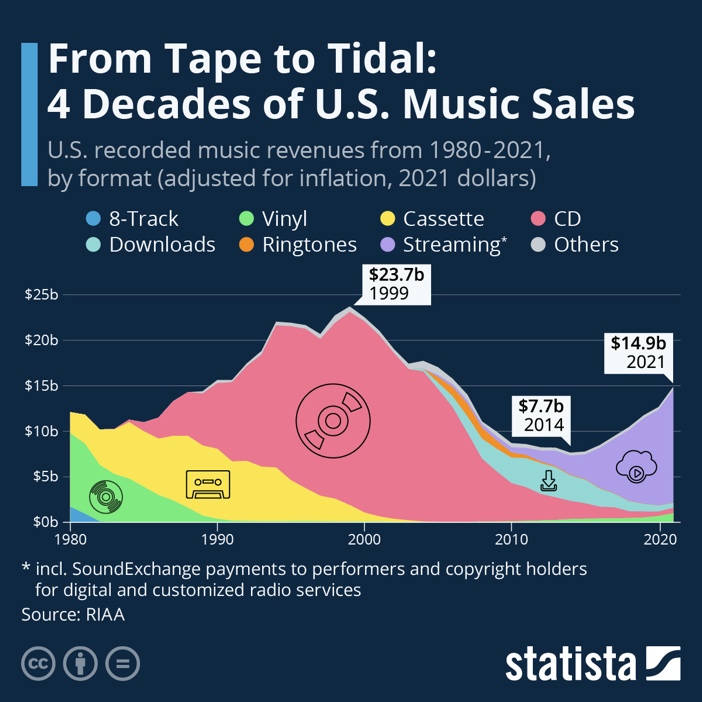

The medium of accessing music has changed rapidly over the course of the last 40 years. From vinyl, to CDs, downloads and now streaming – the industry experienced drastic shifts in technology and consumer preferences. In the early 1980s, vinyl and cassettes used to be the primary way people listened to music, with vinyl alone hovering around $10bn in annual revenues in 1980. However, that quickly changed as CDs arrived. Vinyl revenues declined to virtually zero revenues in early 1990s and were overtaken by the rise of CDs. In fact, CDs became so popular that they allowed the music industry to reach its peak historic revenues of $23.7bn in 1999. Since then, the revenues have been declining until the trough of 2014, dipping to $7.7bn, and have been on the rise in the past decade, yet not near the historic peak.

Source: Statista

Such dynamic is, of course, attributed to the early 2000s, when mobile phones became popular and the web was rapidly expanding. The onset of internet brought way for consumers to download songs and albums online. The most notable platform was Napster, which, illegally, without copyright approvals, made way for people to access music essentially for free. Consumers no longer wanted to visit record stores, and the consumer was now in charge of what is popular. Today and since the early 2010s, streaming is king. Record labels, artists, and investors no longer get revenues from selling physical items; instead, the payout is calculated on a per-stream basis. Per different sources, streaming platforms on average do not even pay a cent per stream. Of the most popular apps, Spotify [NYSE: SPOT] pays $0.003 and Apple Music [NASDAQ: AAPL] $0.008 for every time the consumer listens to a record. Hence, the rapid decline of revenues in the music industry is quite evident.

Bowie Bond

Before the rise of online streaming and file sharing, a unique type of asset-backed security was presented to the world, the Bowie bond. Also called “Pullman bonds” after the banker who created and sold the first bonds of this type, these used income-generating intellectual property as collateral for the security. In detail, the IP assets behind it were royalty streams from current and future album sales, and live performances by David Bowie. These bonds marked one of the first times that IP was collateralised, a practice that is fairly common nowadays. When issued, these bonds had a face value of $1000, an interest rate of 7.9% and a maturity of 10 years. In addition, they were self-liquidating – the principal declined each year. These bonds were attractive to investors, since they were viewed as a stable long-term investment, were rated investment-grade by top credit rating agencies like Moody’s and allowed fans to “own” a part of their favorite artist. However, they were downgraded by Moody’s in 2004 when online music platforms like iTunes gained popularity and record stores declined; the bonds were now just one notch above junk status. Bondholders’ investments tanked; however, the bonds matured and were redeemed in 2007 as planned, there was no default, and the rights to income from songs were given back to Bowie. Today, the idea is still present on Wall Street. Fantex Holdings, for example, issues securities that are tied to the earnings of future athletes to this day.

The Opportunity for Artists

Recorded and published songs are protected by copyright – a legal right that can be sold or licensed by artists to make money from music. Essentially, this means that musicians can sign deals and sell their share of rights to songs to publishers and record labels, which allows to monetize future income streams from their music. There are different rights associated with a record, one of which is for the recording, usually owned by a record label, and another in the performance of a song. Hence the income from a song purchased or performed is divided between the owners of shares in music rights. The reasons artists sell their rights can vary. Some do it to retire and reap the rewards from their work, others have done so during the pandemic, when revenue was lost due to venues being shut and other income streams being cut off or declining. Selling rights provides liquidity to artists, which can be a lucrative way to increase the income from their work. Typically, this is done by seasoned artists close to the end of their careers. A couple recent cases of artists selling their rights are Bruce Springsteen, who received $500m for his life’s work in 2021, and Stevie Nicks, who sold a share of her publishing for $100m in 2020.

A more recent, and quite atypical case of selling rights to song, is Justin Bieber, who sold his catalogue of 290 songs all released before 2022 to Hipgnosis Songs Fund [LON: SONG] for a reported $200m. Being just 28 years old at the time of sale, this marked one of the biggest sales ever made for an artist under the age of 70. The income from performing or selling these songs that would have previously been a royalty payment to Bieber now goes to Hipgnosis. This is possible since Bieber had a record deal with Universal Music Group [AMS: UMG] and a publishing deal with Universal Music Publishing Group, meaning he owned a share of his rights. Now, 100% of his share of publishing copyright for the entire back catalogue is owned by Hipgnosis. Masters, or publishing copyright, have recently seen an uptick in sales, with notable artists like Taylor Swift’s masters also being sold to the private equity company Shamrock Holdings for $300m in March 2020.

While selling the share of publishing copyright is indeed lucrative in the short-term outlook, such decision also implies risks to artists. Simply put, it is possible that artists could make more money by keeping own rights and receiving royalties that in the long run add up to more than the lump-sum sale of rights. As a result, there has been a push back from the music industry, and similar deals are not as well-received as they were just a few years ago.

The Opportunity for Investors

What do most of the songs in your usual playlist have in common? They are probably owned by a private equity fund. Among the thousands of songs owned by private equity funds, there are many you will probably recognize: “Toxic” by Britney Spears, “Don’t Stop Believin’” by Journey, “Single Ladies” by Beyoncé, “Runaway” by Kanye West, “Firework” by Katy Perry, “Can’t stop the feeling” by Justin Timberlake, and “Despacito” by Justin Bieber.

Firms like UK-based Hipgnosis Songs Fund, BlackRock’s Alignment Artist Capital, and AGI Partners’ Unison Fund have recognized the opportunities that investing in this asset class represents. The returns on investment from owning pieces of music are derived from multiple sources. These range from live concerts and tours, public performances in pubs and restaurants, and utilization in films and TV, to now online revenues, which are growing exponentially.

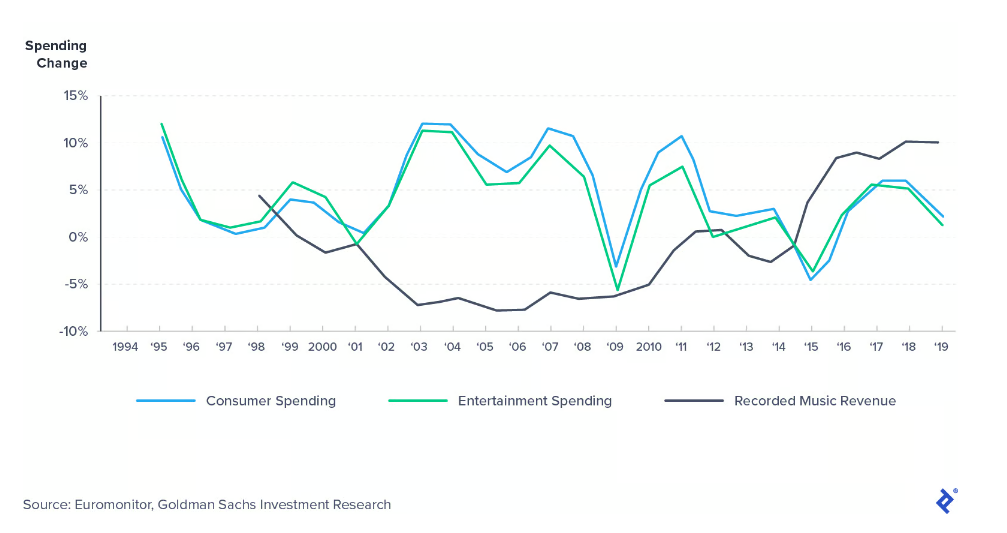

This diversification of sources of income from music-based assets makes these particularly attractive to investors. The model of revenues from a new song or album shows that even though most of the revenue is made closely after the release, a stable and recurring form of income is derived through loyalties for decades in some cases. This income is derived from the royalties from selling the IP rights to various avenues specifically streaming services. This makes the returns have a predictable life and more importantly, they remain uncorrelated to usual market fluctuations. The IP rights also provide an opportunity for capital growth after the rise of streaming services has reversed the decline caused by piracy and lack of demand for physical albums.

Low Correlation of Record Music Spend with Personal Consumer Expenditures (PCE): 1994-2019

Source: Toptal, Finance

Low-interest rate environments where investors are looking for higher yields without taking on considerable amounts of risk are particularly favourable for investments in catalogues which have provided exceptional returns in such cases in the past. Covid was a testament to that as of September 2020: the US 10-year treasury yield was 0.7%, S&P 500 dividend yield was 1.8%, and Vanguard High-yield Corporate Bond (MUTF:VWEHX) yield was 3.9%. Meanwhile, music royalties investments gave much more appealing returns: Royalty Exchange reported that the average annualized return on investment for catalogues sold on its platform was greater than 12%, Hipgnosis Songs Fund’s dividend yield was 4.3% and Mills Music Trust’s [OTC:MMTRS] dividend yield is 9.6%.

These exceptional returns brought three of the biggest private equity funds to show even more interest in the music industry with Blackstone [NYSE:BX] announcing that it had set aside $1bn to buy music in partnership with Merck Mercuriadis’s Hipgnosis investment trust, KKR [NYSE:KKR] planning to acquire some 62,000 songs for $1.1bn, which followed a $1bn fund it had arranged with music group BMG earlier that year and Apollo [NYSE:APO] putting up $1bn to buy songs with a new investment group called HarbourView.

In addition to the inherent reasons that make this asset class attractive, active investors in music IP can actually work to increase the value of their investment through three main approaches. Firstly, investing in emerging artists and songwriters who create new music IP. Fund mangers could take a page out of traditional managers at record labels, who typically spend a lot of resources in recognising new talent that could provide them with exponential returns as they develop into established artists. They can also find creative licensing opportunities for existing music IP through licensing opportunities in film, TV, advertising, cover songs, and video games. This would provide them with new avenues for deriving recurring payments for the assets they already possess and hence increase their return on investment without increasing costs. Finally, they can reduce the transaction costs and payment delays associated with royalty collections caused by the numerous middlemen involved in the process. The complexity of the flow of funds often leads to IP owners having to incur delay in payments for up to a year. Establishing payment networks and infrastructure to reduce this delay as well as the costs associated with it would greatly improve the cashflow management for the funds.

Recent Developments

The advancements made by private equity funds two years ago seemed to provide quite an optimistic outlook regarding the investments in the industry. However, rising interest rates have prevented the initial plans from coming to fruition. The $3bn initially set aside by the giants is yet to be invested due to the rise in borrowing costs causing the catalogue prices to fall. This also lead to them no longer being able to justify loading the assets with as much debt as they had once contemplated due to the decreasing value of the future cash flows music owners could expect to earn.

KKR, an early investor in music royalties, has said to have not bought music for at least a year, and only a few deals have been successfully made under its $1bn partnership. Apollo has also not made a new investment in the industry for at least two years. While HarbourView’s initial fund quietly stopped buying music last year, having spent $200mn of the equity Apollo contributed, but only about $450mn of the $800mn debt the group had considered providing. Blackstone has remained active, spending a bit less than $700mn of its $1bn target on catalogues like Justin Bieber and Justin Timberlake. But it had also been ensnared in a shareholder revolt at Hipgnosis, whose investors voted in October 2023 to restructure the business and rejected a proposal to sell Blackstone some of its assets.

Higher interest rates have also in turn increased the attractiveness of non-music investments that are often more liquid and favoured by traditional financial firms. Combined with the fact that the rise in interest rates decreasing the present value of the future cash flows music owners could expect to earn, meaning that those catalogues could no longer support as much debt as firms such as Apollo and KKR had expected, has led private equity firms to turn their eye to private lending.

As banks retreat from much of the lending they once did, these firms delve deeper into financing credit for firms against secured against catalogues to remain bullish on the music asset class but without facing the issue of lowering valuations due to interest rate hikes. This was the view in an Apollo deal with Concord Music late last year, at a time when the music publisher needed to refinance its existing debts.

Apollo (NYSE:APO) raised $2.3bn in debt for the group in deals secured against a catalogue worth roughly $5bn. Only a portion of the debt was kept by Apollo itself and, its insurance arm Athene, before selling the rest on to other investors and insurers. Hipgnosis and KKR have also raised debt in securitised markets for their music catalogues.

The deal to pay attention to for this industry this year is the takeover of Hipgnosis Songs Fund by US Rival, Concord Chorus for $1.4bn. The takeover values each Hipgnosis share at 93p, approximately 32% above the group’s closing price on the previous day and a small premium to the latest valuation of a music portfolio that includes the catalogues of top artists Justin Timberlake and Shakira. The recent high interest rate environment has created pressure for the firm due to falling valuations and a strategic review of the board last year after a shareholder revolt led to rejection of proposed disposals and a board overhaul.

However, Hipgnosis’ investment adviser- Hipgnosis Song Management, which is backed by Blackstone and whose chairman is Merck Mercuriadis holds a call option under an investment advisory agreement that gives it the right to purchase the fund’s portfolio if and when the agreement is terminated. This could become a hurdle for the deal as the founder Mercauriadis is unlikely to go down without a fight and could hold out for a termination fee as well as a 12-month notice period.

Outlook

In conclusion, it’s clear that the music industry is always in motion: from Bowie bonds to recent acquisitions by private equity firms, there’s been a mix of innovation and adaptation along the way. Moving forward, challenges like rising interest rates and changes in how people consume music will affect the investment landscape, in the same way streaming over the last decade. Despite this, the fundamentals of investing in music remain solid, with diversified revenue streams and music’s everlasting cultural significance in our society. As interest rates stabilise and start coming back down, we can expect private equity funds to resume their deployment of capital into this industry. We can also potentially anticipate a potential reversal of the shift towards investments higher in the capital structure as music royalties can support more debt and their yields falls.

0 Comments