The Sovereign Wealth Fund’s first love – Sports, Media and Entertainment

In October 2021, the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF) completed a £305m takeover of Newcastle United by acquiring an 80% stake from British retail tycoon Mike Ashley. According to research conducted by SPORT+MARKT, the Premier League, England’s first division, has an estimated annual TV audience of 4.7 billion. Newcastle United was the club with the fourth highest average attendance at football games in England between 2013 and 2018. The deal was witnessed by a proportional number of people, causing headlines all over the widely followed footballing world and beyond. However, football clubs are not particularly attractive investments, with high wages often driving cash flows negative and enormous transfer fees resulting in low ROE for investors. Of course, this is not the only investment PIF has made in recent years, with much larger stakes in traditional assets such as stocks, most notably a $8.9bn stake in Lucid Motors [NASDAQ: LCID] and a $2.3bn stake in Uber [NYSE: UBER], which, together with the Utilities Select SPDR ETF account for more than a third of PIF’s total holdings. But somehow investments such as the ones in Newcastle, Activision Blizzard and Electronic Arts, as well as the controversial merger of the PGA Tour and LIV golf have made much bigger headlines recently. In this section we analyse the rationale behind such investments, how they tie together and why they are making headlines.

Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds such as PIF and the QIA (Qatar Investment Authority) are not required to disclose investments, despite active involvement in US markets, which puts them in a unique position of choosing which investments make headlines and which do not. It seems like the ones that end up making headlines follow a common pattern: they are in the sports, media and entertainment industry. Golf fans around the world, estimated to be 450 million in number, were left speechless at the news that one of the world’s largest golf leagues in the world, the PGA tour, merged with a league that did not exist even 3 years ago, the LIV, backed by the Saudi Sovereign Wealth Fund. The new company, in which PIF has a large minority stake, will get the commercial rights under the merger, with the PGA tour effectively getting control of the new entity by having the majority of seats on the board. Basketball and hockey fans were also recently hit with the news that QIA acquired a 5% stake in Monumental Sports and Entertainment (MSE), the parent company of first division local basketball and hockey teams such as Washington, Capitals and the Wizards, as well as E-sports team Wizards District Gaming and WNBA team Washington Mystics. Sailing had a similar fate, with Mubadala Investment Company, the UAE’s sovereign wealth fund, partnering up with SailGP, the largest race on water. Football was also decisively changed by Middle Eastern nations, with the PIF’s acquisition of Newcastle, Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed al-Nahyan, a billionaire member of the Abu Dhabi ruling family acquiring Manchester City and state-backed Qatar Sports Investment buying Paris Saint Germain and Portuguese club Braga in the last few years. Not only that, but the 2022 World Cup was held in Qatar and required a $220bn investment by the QIA.

Dominance across the supply chain

This strong presence by Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds goes deeper than only sports and entertainment, with solid presence in media by the likes of QIA. For instance, the fund owns beIN Sports, a media giant that distributes entertainment, live sports action, and major international events in 43 countries and 7 different languages spanning Europe, North America, Asia, Australia and the Middle East and North Africa. They are also linked with Pitch International, a London-based entertainment agency that raised questions from regulators after it had consistently sold TV rights to English football for the Middle East, North Africa and Western Europe to beIN sport. It turns out that Pitch International, under a complicated ownership structure has a parent company in the Netherlands, called Homer Holding BV, where ownership under 100% is not required to be disclosed. Therefore, a stake of 97.34% in Homer Holding BV is listed as “Shareholder 1” on official records. On top of that, founding documents of the firm cite Hervé de Kervasdoué as original director, the official lawyer of Qatar Sports Investments on the acquisition of PSG in 2011. To go along with this trend, Middle Eastern companies are no strangers to wide media outreach, with Saudi Arabian sporting and entertainment company Sela being the official shirt sponsor of Newcastle United and Qatar Airways having previously sponsored high-profile football clubs such as Bayern Munich, FC Barcelona and PSG.

The rationale behind such investments is clear: sportswashing and soft power. As oil production becomes a less secure revenue source for Gulf States, diversification and the creation of a positive image on the world stage seem to be the top points on these countries’ agendas. Sportswashing is the act of using sports to improve a country’s reputation. This is perfectly exemplified by the 2024 World Cup. Despite high-profile accusations of exploitative and dangerous conditions for migrant workers during preparations for the tournament, held in Qatar, the competition attracted 1.5bn viewers from all over the world. The soft power dimension comes with the investments in media. Commercial rights in football and golf and multi-million-dollar shirt sponsorship deals with sports clubs are just some examples of how Middle Eastern state-backed companies appear on TVs, kits, billboards and stadiums. Profitability remains a question, but aforementioned investments are largely offset by others, with actual high returns, but much less likely to be known by English football fans. Recent investments include Mubadala’s investment in British broadband provider CityFibre and acquisition of a stake in Scandinavian-based communications company GlobalConnect, PIF becoming the second largest stakeholder in Aston Martin and QIA’s $90m Series C investment in biotech company Star Therapeutics.

The road to maturity – a story of Sovereign Wealth Funds becoming more sophisticated

Two decades ago, Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWF’s) held barely $1tn in assets and were not considered significant financial players. Nonetheless, throughout the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2010, SWF’s began attracting attention by taking impressive stakes in the banking sector, symbolizing the rising economic power of these financial institutions from emerging economies. Then, over the next years, these funds expanded considerably in quantity and size, and emerged as true players in global institutional investing. Initially, SWF accumulated huge quantities of dollars thanks to their nations trade surpluses and would mainly reinvest them in US Bonds. However, over the past years there was a shift in their investment thesis and these funds have become more sophisticated, increasingly taking equity positions in foreign firms, increasing the diversity of their investments, and even creating their own asset management arms. As of Feb 2023, SWF’s had over $11tn AUM.

Figure 1: Sovereign Wealth Funds AUM growth over time. Source: Global SWF.

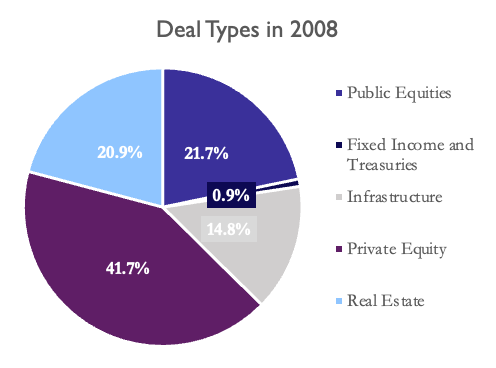

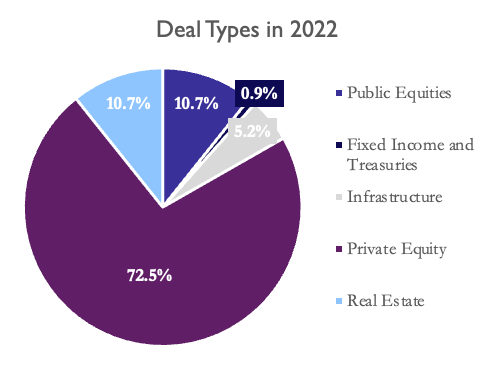

Over the past years, Sovereign Wealth Funds have shifted their investment strategies. While investment in public equities accounted for approximately 21.7% of SWF investments in 2008, they have reduced to 10.7% in 2022. Moreover, SWF have been diversifying and increasing their investments in alternative assets. Global SFW notes than in 2021 SFW’s increased their holdings of alternative assets from 23% in 2016 to 25%. Also, in 2021, SWFs invested more in infrastructure, with funds valued at $15.5bn, which almost doubles the $8.1bn invested in 2020. Furthermore, SWF’s have transferred large amounts of capital out of hedge funds, with 34% of allocations made to hedge funds in 2016, that value decreasing to 11% by 2020. This capital has been mostly allocated into real assets, such as real estate and infrastructure. Something to consider is the SWF preference for investments with higher expected risks and returns. As of 2020, for infrastructure, 32% of commitments were to value-added strategies while 10% to opportunistic strategies (Preqin, 2021). Overall, SFW’s are showing a positive trend towards allocations into private equity and infrastructure, a negative trend towards allocations in public equities and fixed income, and a somehow stable trend in allocations in real estate and Hedge Funds.

Figure 2: Comparison of SWF deal types, 2008 vs. 2022. The figure compares the breakdown, in percentage, of SFW deal types. Source: Sovereign wealth funds in the post pandemic era (2023, Megginson, Malik, Zhou).

Ward, Brill and Raco (2022) claim that a considerable amount of the SFW shift in investments towards real estate can be attributed to geopolitics, along with the opportunity to improve the nations reputation. The authors claim that foreign states can exert soft power because of the investments SFWs and its citizens make. For example, in the past, Russia has used the flows of capital into foreign real estate markets as a source of leverage. Furthermore, after the Great Financial Crisis, significant amounts of capital from SFW’s went into the London real estate market, peaking at over $16bn in 2013. Moreover, five out of the twenty largest property holders in London are SWF’s, with the Qatari Investment Authority (QIA) leading the way. This SWF, through its wholly owned subsidiary Qatari Diar, formed a joint venture with Delancey, a UK-based real estate asset manager, called QDD. This joint venture, following the 2012 Olympics, acquired the former Olympic houses, and transformed them into what is known today as The East Village, a +1k housing development aimed at middle-class professionals. This created the first Build-to-Rent site open in London, a program which has gradually expanded throughout the UK. Thanks to the success of The East Village, the Qatari government improved its relationship with UK politicians, and gained increased influence, as the SWF directly contributed to alleviate the London’s housing crisis, an extremely pressing issue. Consequently, through investments in real estate, SWF’s increase their presence and influence over other nations, making them a very strategic investment.

On the other hand, the increase in private equity investments can be attributed to an attempt to reduce the hostility that investments from SWF’s may generate. Due to their unique structures, which may include the presence of active politicians on their boards, the potential national security implications, inherent opacity, and possible conflicts of interest, SWF’s often employ investment vehicles as a means to establish relationships with foreign companies. An example of this would be PIF having investment stakes both in Blackstone and in SoftBank’s Vision Fund. This strategic approach enables SWFs to address and mitigate potential sources of hostilities. SWF’s are more likely to invest via an investment vehicles as it allows them to signal a hands-off investment strategy, which decreases adverse regulatory consequences such as governmental examination, prohibitions on strategic industries, and capital requirements, as well as eliminates the possible concerns of that the acquisition will be used to exert external political influence over foreign firms, among others. Murtino and Scalera (2016) through the use of multinomial logistic estimates show that SWF’s that are characterized as opaque and/or politized are more likely to invest through investment vehicles, as well that SFW’s who acquire firms that operate on strategic industries or acquire majority equity stakes, are also more likely to do so through investment vehicles. Consequently, the increase in the use of investment vehicles such as private equity houses can be associated to an attempt by SWF’s to decrease the hostility their investments might generate both to their target companies and regulators. Moreover, the increase in the use of PE’s houses has led to differentiated investment strategies for the SWF’s.

Partnering with Traditional Private Equity Funds

Traditionally, there were two methods through which SWF’s invest in private equity. The first method is through PE funds through a limited partner (LP) investment that is separated from the SWF. As private equities are considered a risky asset class, this type of investment mostly pursues the possibility of maximizing returns on the portfolio. When the investment is done via an LP, the SFW does not have the ability to directly target specific companies. Therefore, eliminating the risk of investments being interpreted as politically motivated. The second method is to make direct investments into selected companies rather than through a PE fund. Through this mechanism, the SWF avoid management fees and have larger control over their investments. Nonetheless, their exposure to potential hostilities by regulatory bodies increases and the investment can be characterized as of political nature. Moreover, over the past years a new method has appeared. In this, the SWF co-invests with a strategic partner, making jointly sponsored deals. According to Bortolotti and Scortecci (2019), over the past decade, SWF’s have shifted away from the conventional LP model and rather embraced a more collaborative approach with direct equity partnership. Over the 2009 to 2018 period, direct equity partnership increased from 19% to 61% of total deals, while solo investments fell from 69% to 21%. Hence, this shift in structure has opened the opportunity for a partnership in which the PE houses contributed with their expertise and due diligence capacities, while the SWF’s provide the capital they need, usually leading to significant returns.

One of the most relevant SWF’s – PE’s partnership is the one between Mubadala Investment Company, the second-largest Abu Dhabi based state investor and Apollo [NYSE: APO], a leading global alternative asset manager, mostly recognized for their private credit business line. Founded in 2020, Apollo’s Strategic Origination Partner fund aimed at providing approximately $12bn in financing over the next three years, targeting opportunities of approximately $1bn to help meet the pressing corporate demands for direct scaled origination solutions. The platform builds on Apollo’s decades of experience of providing capital solutions to large issuers in the need of financing solutions that sit between Apollo’s existing middle-market direct lending platform and the syndicated loan market. Hence, providing Mubadala access to the lending market of high quality and caliber businesses. Moreover, in 2022, both companies announced the expansion of their ongoing global partnership, which includes multiple strategic initiatives across Apollo’s global and integrated platform. This comes at a time of increasing demand for personalized multi-billion-dollar equity and debt solutions, as a result of the pressing macroeconomic environment, with rising interest rates and continued inflationary pressure. Private credit investments are designed to perform across all market cycles. Furthermore, this growing partnership hasn’t restricted itself to the credit market, but also includes taking stakes in companies as Brightspeed, a U.S based broadband and telecommunications service company. Consequently, strategic partnerships like this one between Mubadala and Apollo are highly mutually beneficial as the expertise provided by one of the parties, along with the capital from the other, drives growth and creates opportunities for both organizations.

Another example of a partnership between a SWF and a PE, was that between Mubadala and KKR, a leading global investment firm, in the acquisition of CoolIt Systems, for $270m, in May 2023. CoolIt Systems, a Canadian company, specialized in scalable liquid cooling solutions for computers, created a patented technology that reduces operating costs and carbon emissions from data centres and digital infrastructure. With the data centre industry expected to consume around 8% of the world’s energy by 2030, their proprietary technology plays a pivotal role in the reduction of emissions. KKR invested in CoolIt thorough its Global Impact strategy, which aims to identify and invest in opportunities whose financial performance and societal impact are aligned. On the other hand, Mubadala aims to lever their long-term horizon by investing in industries that will shape the future and promote carbon neutrality. Moreover, the target company will benefit from KKR’s expertise and resources, as well as of Mubadala’s capital, prompting further growth and development of clean technologies. Consequently, through joint ventures between PE houses and SWF’s, not only both the financial sponsors obtain clear benefits, but companies receive funds and expertise crucial for their development, leading to accelerated growth and enhanced competitiveness.

Nonetheless, not all examples of partnerships between PE houses and SWF’s have been successful. The Softbank Vision Fund was founded in 2017 and had as investors the Softbank Group, the Japanese multinational investment holding, the Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia (PIF), Mubadala Investment Company, and Apple, among others, for a total of $100bn. Nonetheless, by May 2020, Softbank had already announced the fund had lost $18bn, because of many companies poor performance and high-profile debacles of the failed WeWork IPO. Moreover, for the fiscal year 2021-2022, the Vision Fund further lost $27.4bn, followed by a loss of $32bn for the 2022-2023 fiscal year, because of costly failures such as Katerra, FTX, Kabbage, Wirecard, Zymergen, and overall weak tech valuations.

Moreover, Sovereign Wealth Funds, have created their own private equity arms. Mubadala Capital, subsidiary of the Mubadala Investment Company, has approximately $20bn in AUM. Established in 2011, it operates four lines of businesses that include private equity, venture capital and alternative solutions, as well as a Brazil-focused investment business. Along with its own funds, Mubadala Capital manages around $13bn in third-party capital on behalf of institutional investors, family offices, among others. Their investment thesis is based in the premise of generating attractive risk-adjusted returns by combining Mubadala’s sole ownership and experience, whether through sourcing, due diligence, or value creation as an owner. Among its significant transactions are the $2.1bn equity partnership with Ardian, the French-based PE firm, as well as an agreement with Petrobras, Brazil’s leading petroleum company, to produce biofuels. Moreover, along Mubadala Capital’s investors is Apollo, once again highlighting the intertwined relationship between SWF’s and PE’s.

Conclusion

On September 5th, 2023, Saudi Telecom, in collaboration with PIF, announced the acquisition of a 10% stake in Spain’s Telefonica, with the government in Madrid claiming that they will do all possible to defend strategic assets such as the country’s largest telecom business. Middle Eastern Sovereign Wealth Funds have become more sophisticated, since the acquisition of PSG by QIS in 2011, their PE arms now focusing on strategic assets, real estate investments and infrastructure. However, this is only part of the new reality, as ME investors continue to place large bets on “flashy investments”, with the scope of increasing their soft power and reputation. It is to be seen how in the near future European regulators will react to more and more oil money pouring on the old continent.

0 Comments