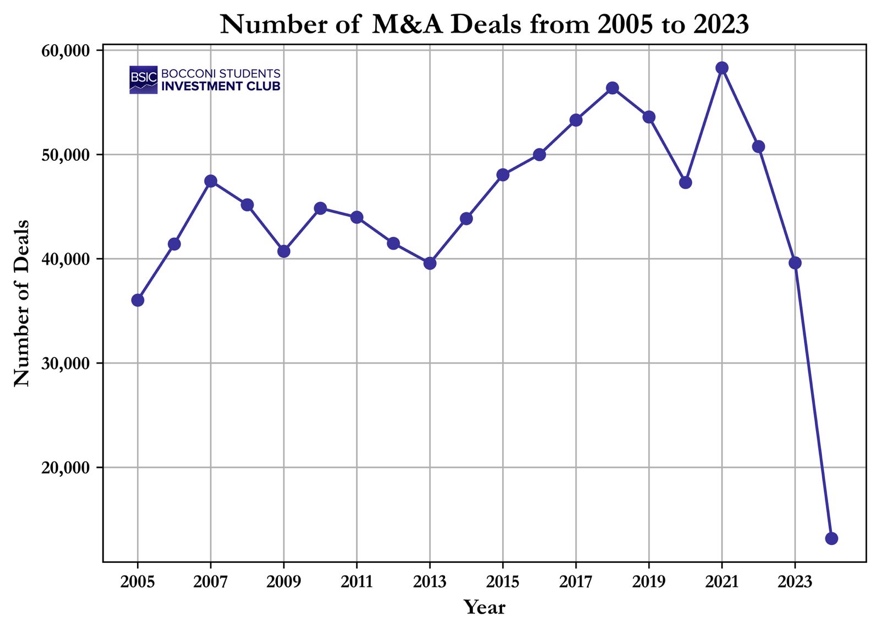

What has happened in the last 5 years?

Over the past five years, M&A activity has experienced dramatic fluctuations, reaching both record highs and record lows. The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 brought deal activity to a near standstill as companies prioritised safeguarding employees’ health and maintaining daily operations amidst unprecedented uncertainty. However, in the second half of the year, increasing clarity about the future and generous government stimulus funding prompted executives to turn to M&A to position themselves for success in the post-pandemic world and capitalise on changing consumer preferences.

By 2021, the global market rebounded spectacularly and hit record levels of $5.7tn, fuelled by low interest rates, abundant liquidity and pent-up demand. Digital M&A became the new norm, while localisation and strengthening role of regulators continued their momentum. Although North America led the market, accounting for 49.3% of worldwide deals, Europe also experienced record-breaking M&A activity, reaching $1.3tn, up from $900bn in 2020. The largest transaction globally was AT&T’s [NYSE: T] $96bn divestment of WarnerMedia [NASDAQ: WBD] to Discovery [NASDAQ: WBD], marking the humbling retreat of the US media group from streaming services. Additionally, other important deals concluded included Dell’s [NYSE: DELL] $62bn spin-off of its 81% stake in VMware [NYSE: VMW] and the largest leveraged buyout of the year for Medline Industries Inc, valued at $34bn. In terms of sector performance, technology and healthcare led the way. The tech sector achieved a total deal value of $808bn, propelled by the pandemic-driven acceleration of digital transformation. Buyers were willing to pay significant premiums, reflected by a median EV/EBITDA multiple of 25x. Notable deals included Microsoft’s [NASDAQ: MSFT] $19.7bn acquisition of Nuance Communications and Block’s (formerly Square) [NYSE: SQ] $29bn acquisition of Afterpay. Healthcare also saw acquisition costs rise sharply, with the median multiple hitting a record 20x. The restructuring of both General Electric [NYSE: GE] and Johnson & Johnson [NYSE: JNJ] into standalone healthcare companies underscored the growing push for focus, scale, and specialisation across all healthcare subsectors. Furthermore, the surge in IPOs underscored the rebound of corporate dealmaking, with major debuts like dating app Bumble’s [NASDAQ: BMBL] $2.2bn IPO and two EV-makers – Rivian [NASDAQ: RIVN] raising $11.9bn and Lucid Motors [NASDAQ: LCID], which despite not having a vehicle on the market managed to raise $4.5bn through a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC). SPACs are essentially “blank-check” public companies, created for the sole purpose of acquiring a private company and thus making it public without the need of a formal IPO underwriting process. They played a particularly important role in 2021, accounting for $617bn-worth of global transactions, but started facing regulatory scrutiny towards the end of the year. This rise of SPACs was in line with the increasing diversification of the types of deals and dealmakers participating in M&A. For instance, in 2021 private equity was involved in almost 40% of total deals, showcasing its quest for larger deals.

After the 2021 frenzy, the M&A market started to cool in 2022 due to surging inflation, rising interest rates and geopolitical tensions such as the Russia-Ukraine war. By 2023, global deal value dropped by 15% to around $3.2tn, its lowest level in a decade. A significant driver of the drop was the widening gap between what sellers demanded and what buyers were willing to spend, leading to a nerve-wracking game of “who would blink first”. Low deal multiples (overall EV/EBITDA of 10.1, lowest in 15 years) combined with robust stock prices and the absence of a fair market value benchmarks from a decline in PE exits made it increasingly difficult to close the valuation gap, leading to fewer completed transactions. Sectors that thrived during the previous boom experienced steep declines, with tech deals plummeting by 45% in value as EV/EBITDA multiples fell from 25x to 13x, primarily weighed down by rising interest rates. However, other sectors such as healthcare, energy and natural resources managed to stay resilient. In particular, rising commodity prices led to a 17% y-o-y rise in energy deal values with two notable megadeals – Chevron’s [NYSE: CVX] $53bn acquisition of Hess [NYSE: HESS] and ExxonMobil’s [NYSE: XOM] $60bn deal for Pioneer Natural Resources [NYSE: PXD]. Healthcare also maintained its M&A momentum with a focus on economies of scope, exemplified by biopharmaceutical giant AbbVie’s [NYSE: ABBV] acquisitions of ImmunoGen [NASDAQ: IMGN], a leader in oncology, and Cerevel Therapeutics [NASDAQ: CERE], specializing in neuroscience. Other major trends were the presence of vertical dealmaking, especially in automotives, increasing the importance of spin-offs in portfolio transformation and cross-border transactions, which despite getting trickier due to regulatory hurdles remained a useful tool for portfolio enhancement in more favourable markets.

Source: Statista, BSIC

What is turning the tide?

Macroeconomic factors driving the resurgence of deal-making in 2024 include a clearer economic outlook, as inflation has eased and the anticipated recession has yet to materialize, with consensus leaning towards a soft landing. The US labour market remains resilient, while consumer spending stays robust, supporting economic stability. Interest rate cuts by Switzerland, Sweden, Canada, and the ECB have created a more favourable environment for M&A, and just two weeks ago, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates by 50 basis points for the first time since the early days of the pandemic in 2020. While uncertainty lingers, it may present upside, allowing dealmakers to take calculated risks. M&A is expected to return, though the exact timing is unclear. Some sectors will bounce back faster than others, and businesses seeking dynamic growth will turn to M&A more rapidly than others as they are forced to rethink strategy. Many are looking to invest in AI, a sector seen as a critical disruptor and a potential source of cost efficiencies. Other drivers include sponsors facing exit pressure and new sources of private capital as sovereign wealth funds and family offices are looking to invest. Investments in the sustainability transition, automation for operational efficiency, and distressed M&A, driven by the ongoing high-rate environment which has put pressure on overleveraged firms, are also pushing activity, while megadeals are making a comeback, especially in technology and energy. With organic growth being challenging in these sectors due to the risk of falling behind, buying in seems like the next best option as internal innovation and development are slower and carry higher risks in this fast-paced environment. Although we have seen large deals in the first half of 2024, which drove up overall deal value, it stays below the ten-year average, and the amount of deals is still down by 25% compared to H1 2023, continuing the decreasing trend that started in 2022. Companies with accumulated cash and a strategic need to act are expected to play a vital role in early-cycle acquisitions, which have historically led to stronger performance.

2024

As the 2024 M&A season unfolds, a string of megadeals has already made news headlines. Large corporations have indeed stepped off the sidelines, driving an increase in deal value in the first nine months of the year to $2.3tn, up 17% from the same period in 2023. Among the blockbuster deals that have closed, 2024 saw Mars’s $36bn acquisition of Pringles maker Kellanova [NYSE: K]. With recent price increases, brands under Kellanova, created in 2023 after Kellogg span-off its breakfast cereals and snacks divisions, performed well, even upgrading 2024 sales forecasts after strong revenue growth in recent months. However, it is believed that this is unsustainable as consumer preferences shift towards healthier snacks and private label brands. Moreover, with the rise of weight loss drugs (GLP-1) and inflation worries consumers are expected to snack less in the future. Within this environment, the large premium Mars paid – 69% above Kellanova’s recent share price, seems rather pricey even for the tight snack industry, but also shows Mars’ confidence in the value-generating capability of entering the salty snack and cereal markets. Additionally, the geographical reach of Kellanova, especially in regions like Africa and Latin America align with Mars’ goal of expanding its global footprint.

Another major successful deal has been Verizon’s [NYSE: VZ] $20bn takeover of Frontier Communications [NASDAQ: FYBR]. The all-cash transaction is part of a broader trend of consolidation in the fibre internet industry, driven by the growing demand for faster broadband services. Frontier has been a potential target ever since it emerged from bankruptcy in 2021 and its acquisition by Verizon was a logical step, that would allow it to be more competitive in markets it had previously been underrepresented in. The deal is expected to generate at least $500m in annual cost savings by year three, further strengthening Verizon’s operational efficiency. However, some analysts suggest there could still be competing bids from other telecom giants such as AT&T [NYSE: T] or T-Mobile [NASDAQ: TMUS], reflecting the heightened interest in acquiring broadband infrastructure.

The €14.3bn sale of Deutsche Bahn’s logistics to DSV [CPH: DSV], including €11.3bn in equity marked a transformative deal that would make the Danish DSV the largest logistics management provider in the world. From the point of view of Deutsche Bahn, the sale is intended to help it pay down its debt, while for DSV it represents the culmination of decades of aggressive growth through acquisitions, allowing it to surpass logistics giants such as DHL [FWB: DHL] and Kuehne + Nagel [SIX: KNIN] in terms of revenue.

The oil and gas sector has also witnessed consolidation, led by ExxonMobil’s [NYSE: XOM] $60bn acquisition of Pioneer Natural Resources [NYSE: PXD] in 2023, which spurred additional deals in the following year such as the $37bn spin-off of GE Vernova [NYSE: GEV] and Diamondback Energy’s [NASDAQ: FANG] $26bn acquisition of Endeavor Energy Resources. Looking ahead, advisers predict a similar wave of activity in the technology sector, with Synopsys’s [NASDAQ: SNPS] $35bn acquisition of Ansys [NASDAQ: ANSS] marking a key merger in the software industry and raising hopes for more strategic combinations. Moreover, PE moves such as Blackstone’s [NYSE: BX] $24bn purchase of Australian data centre platform AirTrunk and Silver Lake’s $13bn acquisition of sports and entertainment giant Endeavor [NYSE: EDR] show that the “wait-and-see” approach of private equity companies is now a thing of the past.

These major moves clearly point to a shift in sentiment across boardrooms, gaining confidence on the back of optimism for a soft landing and continued path of interest rate cuts in the coming months.

Potential deals that are expected to close in 2024

Although deal-making recovery remains cautious for 2024, as financing is still challenging, several high-profile transactions are expected to close. One key deal is Qualcomm’s [NASDAQ: QCOM] potential takeover of Intel [NASDAQ: INTC]. Intel is up for sale as they have had a disastrous H1 2024, reporting poor earnings as well cash flow decreasing significantly over the last three years. This financial strain, in addition to a share price decline of more than 50% since the start of the year, has Intel announcing layoffs of 15,000 employees, cost cuts, and a cancellation of the dividend payments, which at its best times used to have a payout of $6bn. Qualcomm has expressed a friendly interest in acquiring Intel in what appears to be a strategic, rather than hostile, move. The deal would position Qualcomm to benefit from Intel’s chip manufacturing capabilities, an area where Qualcomm currently falls short. However, Intel’s shareholders may not see substantial upside from the potential deal, mainly if it’s completed at a lower valuation due to Intel’s current struggles. If there were to be a full takeover, it would be the largest tech deal in history, as Intel’s market cap is standing at around $100bn. However, such an acquisition seems unlikely due to regulatory and strategic hurdles. Moreover, a lengthy process could risk both companies falling behind in the fast-paced semiconductor industry, especially with pressure from fierce Chinese competition. Qualcomm is short on cash reserves and would likely need to finance the deal by using a combination of debt and equity. Intel is being advised by Goldman Sachs [NYSE: GS] and Morgan Stanley [NYSE: MS] , while Qualcomm has enlisted Evercore [NYSE: EVR] to explore the possibility of what could be a game-changing transaction in the tech industry.

Driven by the European banking sector’s need for consolidation to compete on a global scale, Italian bank UniCredit [BIT: UCG] has quietly accumulated a 21% stake in the German Commerzbank [DE: CBK] with hopes to close a deal on a full acquisition. While Germany has advocated for creating larger European banks and necessary mergers, it seems that this will only happen on their own terms. There has been resistance from the German government, trade unions and Commerzbank’s most significant client group, the German Mittelstand (SME). The former has raised the concern that lending and risk management could be relocated to Italy, which could diminish Frankfurt’s status as a financial hub. Additionally, there is a fear of losing the prominent role in funding the Mittelstand, which has provided $99bn in funding in 2024 by the end of June, and its 30% market share in foreign trade finance could be jeopardized. Nevertheless, this might be overstated as UniCredit has a clear intention to expand lending activities and, more specifically, target the German corporate market. Scaring loyal customers away would be counterintuitive to that goal. While the Mittelstand worries about less favourable terms from an Italian parent company, it’s worth noting that debt in Italy is not more expensive than in Germany. For both banks, balance sheets and profitability would improve through a merger, and an enlarged lender might even be a more reliable partner for corporates, given the increase in resources. The competition sees a potential merger more favourably, as some customers may look for other lenders to diversify access to financing. Currently, UniCredit is awaiting approval by the European Central Bank (ECB), which is expected to be in line with the EU’s broader objectives of consolidation. The question, however, is how long this approval might take and if UniCredit maintains its interest in the meantime. Especially given that its derivative-based share accumulation strategy allowing it to walk away without significant losses if necessary. To read more about this situation in detail, consult our article from two weeks ago: UniCredit x Commerzbank – Towards a European Banking Union.

As sponsors are under pressure to return cash to investors following a dry spell in IPOs and takeovers, some have become more active in the market. Apollo [NYSE: APO], though widely known today for its insurance, buyout and credit strategies, originally built its reputation in the 1990s as a distressed investing specialist. Recently, Apollo has shown interest in Intel by partnering with Qualcomm on a potential acquisition of a proposed $5bn equity-like investment in the company. Interestingly, Apollo has a pre-existing relationship with Intel as it acquired 49% equity in Intel’s Ireland facility for $11bn as part of the Semiconductor Co-Investment Program (SCIP). As a rebound is expected for Intel, market analysts are suggesting that a sponsor like Apollo might be a better fit to help the company’s recovery, compared to the teaser offer by Qualcomm. Apollo’s experience in distressed situations could position it as a valuable partner in navigating Intel’s turnaround.

Additionally, US private equity group TPG [NASDAQ: TPG] is set to buy German metering company Techem for up to $7bn. Techem, which offers devices that help households monitor their energy and water usage, has seen rising investor interest as sustainable power usage trends. TPG’s investment will be made in partnership with Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund GIC, and through its TPG Rise Climate fund, which is dedicated to sustainability-focused investments. Techem is currently owned by Swiss PE Partners group [SWX: PGHN], which acquired Techem in 2018 for €4.6bn. If this deal is successful, it would rank among the largest buyout transactions between private equity firms in Europe.

Case Study: UK M&A market

An introduction to the City Code and the Panel

UK takeovers of public and certain private companies are governed by the City Code on Takeovers and Mergers (the City Code), which is issued and administrated by the Panel of Takeovers and Mergers (the Panel). The City Code applies to all offers for public companies with registered offices in the UK, Channel Islands and the Isle of Man and whose assets are traded on a UK regulatory market, any stock exchange based in the Isle of Man or Channel Islands, or a UK multilateral trading facility. Lastly, the City Code applies to offers to private companies which have registered offices in the UK, Channel Islands, and Isle of Man and if they are considered to have central management and control in the aforementioned jurisdictions. The rules are split between six general principles and 38 detailed rules. The general principles aim to formalize the approach of the Panel to all issues. One of the most important ones is that all shareholders must be treated equally. Furthermore, the Panel also issues Practice Statements in which it shows how the Panel interprets the City Code. What is worth noting is that the City Code considers only the process of a takeover, but doesn’t consider company financials or anti-trust concerns.

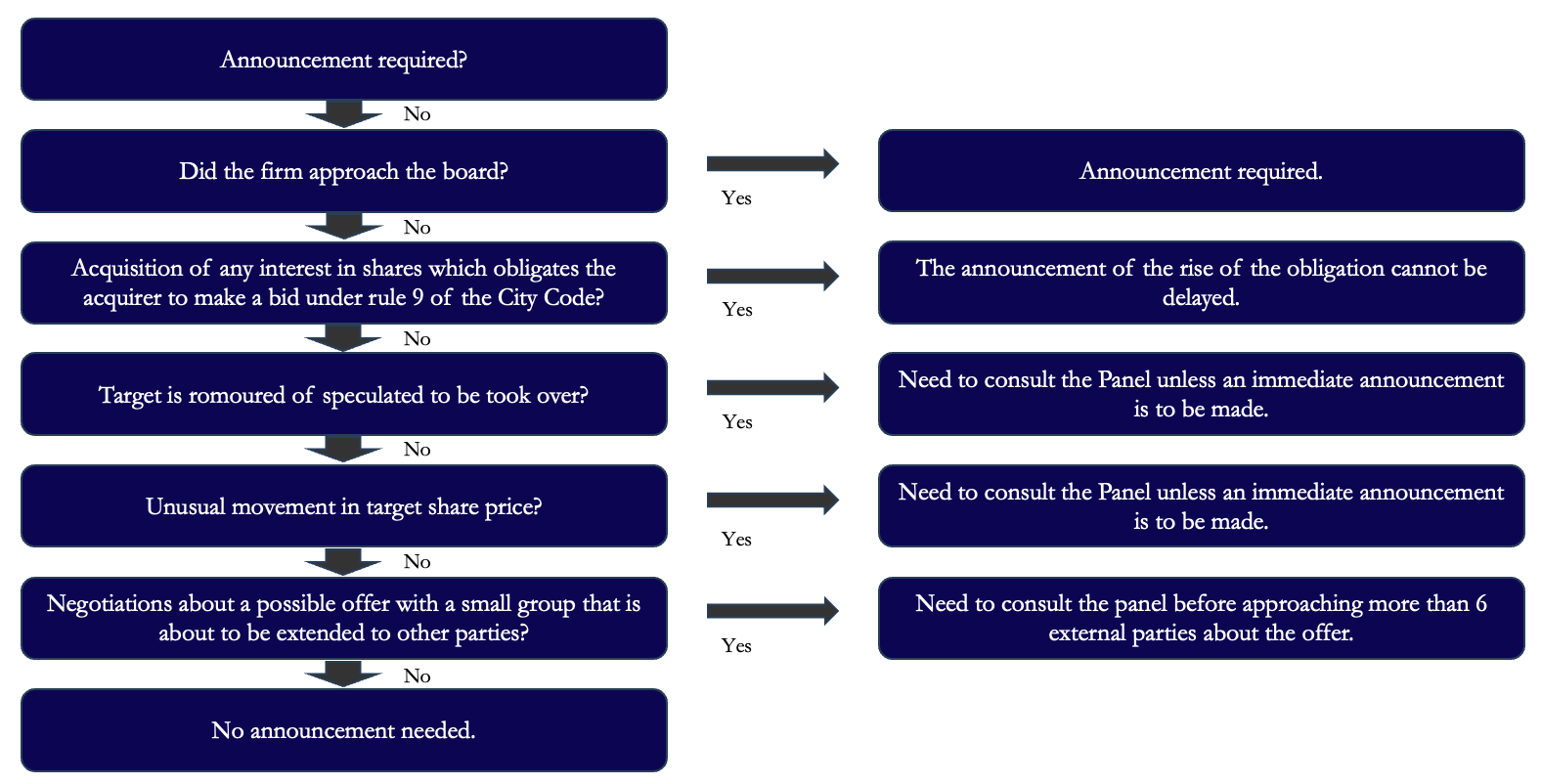

Announcement requirements and the resulting obligations

Before an announcement is made, it is crucial to preserve secrecy, especially regarding price-sensitive information. There is only one case in which such information may be passed to another party and it is when it is absolutely necessary, and the party is aware of the need for secrecy. Under the City Code, the announcement must be made by the acquiring company, if there has not been any previous approach to the seller’s board. In the other case, the responsibility of making an announcement is usually on the target company, unless the board has rejected the offer, then the obligation of making an announcement goes back to the acquiring company. There are 5 main criteria which determine whether an announcement is due or not. In certain cases, a dispensation of the announcement can be requested, but this will impose some restrictions on the buyer. One of the most important ones is that the bidder cannot express intent to acquire the target company for 6 months. Furthermore, the bidder cannot within 3 months of the dispensation actively consider making an offer for the target company, approach the board of the target regarding an offer, and it cannot acquire an interest in the target shares. If the dispensation was not granted there is nothing that can stop the target company in announcing the refusal of the offer and revealing any bidders that took part in the process even if still weren’t rejected. The announcement under the City Code is a significant event which will oblige the bidder to proceed with the offer and its documentation within 28 days. A company may also decide to do a possible offer announcement which will not bind the company to proceed with an offer within the 28-day period but it will oblige them to announce a potential offer within that time frame or withdraw from the pursuit of the takeover (also known as the “put up or shut up” (PUSU) deadline). What is important is that if any details of the offer are put on the announcement the bidder may be held accountable and be forced to proceed with the announced terms. The target company may also ask for an extension of the PUSU deadline, but it must be agreed by the Panel. If the company decides to abandon the pursuit of a takeover it may announce a no intention to bid announcement. This will trigger some restrictions to the bidder such as a 6-month restriction on announcing an offer or a possible offer for the target.

Source: BSIC

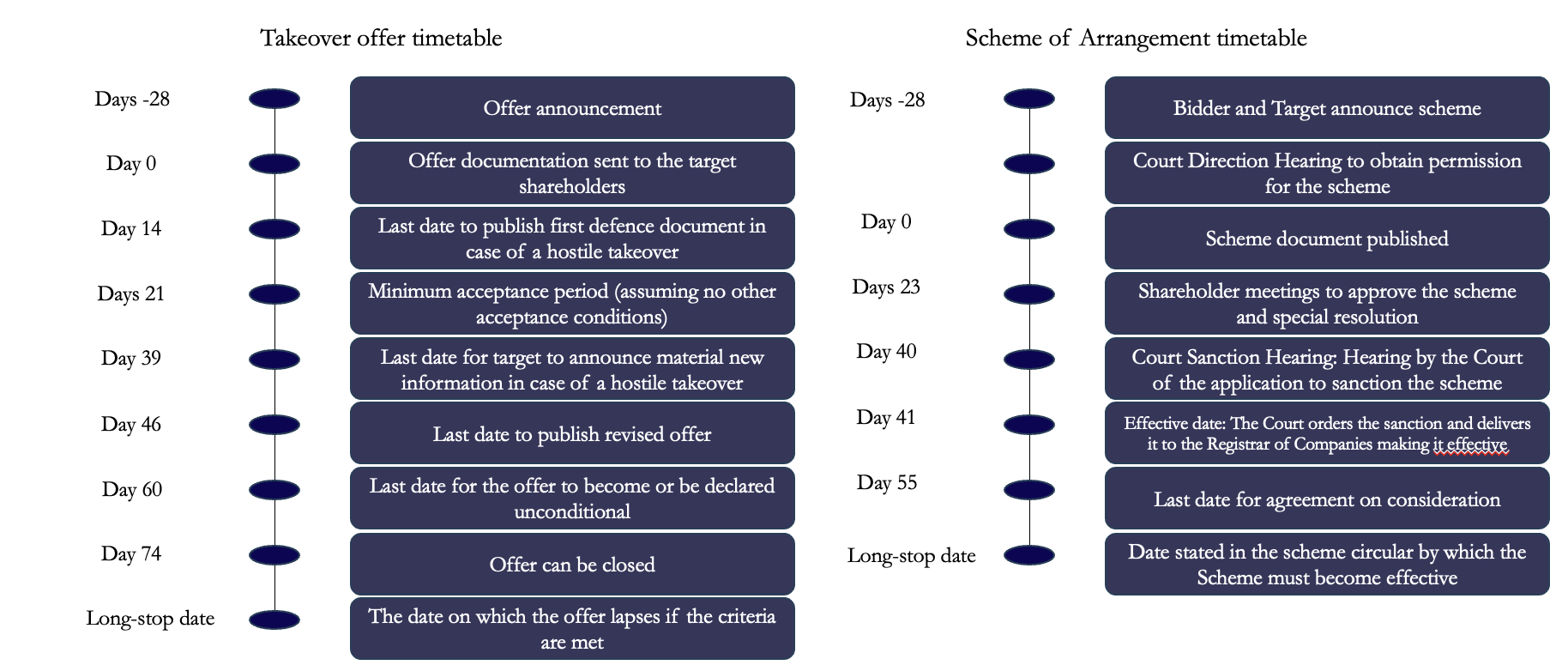

Offer structure, timetables, and deal protection

There are 2 ways of implementing a public takeover: contractual takeover or scheme of arrangement. Under a contractual takeover, the bidder makes a general offer to all shareholders. To declare the offer unconditional, the bidder must manage to acquire at least 50% of the shares, and to be able to acquire the minority, the bidder must acquire at least 90% of the shares. For this reason, the bidder usually sets the acceptance condition at 90% instead of 50%, but the condition is structured in a way that the bidder can reduce the threshold to 50% if needed. A scheme of arrangement on the other hand is an offer made to specific shareholders, governed by the Companies Act 2006. This type of takeover must be approved by the shareholders and the High Court, which makes the structure of a scheme of arrangement less flexible. On the other hand, a Scheme of Arrangement allows the company to acquire 100% of the company by convincing only 75% of the shareholders. Once a deal closes, the City Code provides many protective measures that safeguard the interests of the bidder and target. Examples of such measures are the prohibition of “offer-related agreements” between bidders and target and break-up fees.

Source: BSIC

Comparison between US and UK takeover procedures

There are many differences in the way that the US and the UK takeovers work. The UK has an independent body (the Panel) which takes care of takeover law, but there is no such institution in the US as the SEC (Security Exchange Commission) is an institution that forces federal laws on takeovers. Under the City Code, a bidder is obliged to proceed with a tender offer if they acquire over 30% of the shares to preserve the interest of the minority shareholders, while in the US there is no such provision besides the Schedule 13-D, which is triggered when a potential bidder acquires more than 5% of a company, and over 2% was acquired in the last 12 months. The Schedule 13-D provision forces the acquiring company to either commit to the intent of pursuing further ownership in the future, or declaring a lack of interest in expanding their influence. Furthermore, in the UK jurisdiction, the White Knight Defence is allowed which consists of a third-party company making a bid for the target with the aim of making the target less attractive. Financing disclosure rules are also different as in the UK the company must provide evidence of being able to finance the takeover, while in the US the rules are less strict, but the bidder must have enough resources to complete the acquisition. Lastly, the poison pill defence, which is a defence tactic which makes it harder for the bidder to acquire a majority by diluting the total share count through issuing discounted shares to its current shareholder, is allowed under UK takeover rules while in the US it is highly scrutinised by the SEC.

The Rightmove Saga

REA [AX: REA] is the biggest property listing group in Australia and on Sept. 2nd announced the first takeover offer for the UK-listed Rightmove [LSE: RMV], effectively starting the PUSP provision which set up a 28-day deadline on Sept. 30th to finalise the offer. The rationale behind the acquisition was to accelerate the expansion of Rightmove into commercial property listing and real estate data. The attractiveness of Rightmove has been shown by RAEs’ 4 offers during the PUSU period, raising the initial offer from $5.6bn to $6.2bn, which represented a 44% premium in respect to its unaffected share price on the 30th of August. Although the premium was high, the offer was unattractive due to the form of consideration consisting of cash and REA stock. The reason for the rejection was the board’s optimism regarding Rightmove’s future and growth plans, hoping to double its operating profits in the next 2 years. Furthermore, the REA shares are considered unattractive because many UK-investors have an investing strategy which revolves around UK-listed companies. An acquisition from REA would force them to instantly sell off the REA stock which will decrease the stock price, negatively affecting Rightmove shareholders. Secondly there needs to be a belief that REA stocks are undervalued for the offer to be attractive for Rightmove shareholders, but due to REA trading at a premium to comparable companies in Australia, and its share price dropping by 10% since its pursuit of Rightmove, this led to the decision to reject the REA takeover offer.

UK takeover premiums

There has been $78bn worth of bids for London-listed companies this year, with most of them coming from international buyers. This has skyrocketed the premium paid for UK listed companies which reached highest levels since 2018. The recovery is driven by low share prices and expectations that interest rates have peaked due to the taming of inflation. The suppressed share prices can be seen especially by observing that the London’s blue-chip FTSE 100 index, which is trading at 12 times earnings compared to the 17 times earning of global equities. M&A activity has been rising thanks to positive signs from the economy, but there is still a lot of uncertainty related to geopolitical risks.

Our Outlook on the M&A market

The main sectors driving the M&A recovery in H1 2024 have been energy and technology. Firstly, Oil and Gas companies have a lot of cash on their balance sheet, incentivising them to pursue inorganic growth due to the high opportunity cost of holding cash. Renewable energies have become a very attractive asset, specifically due to the Inflation Reduction Act and related subsidies (especially in the US). Secondly, technology was driven mainly by Artificial Intelligence. AI is a technology which provides the highest benefits with scale, as LLMs provide the best performance when paired with large amounts of data and GPUs, and better infrastructure, leading to a better product.

Although we had a recovery in the EMEA and US regions in terms of M&A activity, the main driver of it was strategic M&A. The discrepancy between strategic and sponsor M&A lies in the type of funding used by the acquirers. Due to the relatively high stock prices of companies, strategic buyers can leverage it by choosing stock as a form of consideration instead of cash, which allows them to disregard the high cost of debt. On the other hand, Private Equity firms heavily rely on leverage to perform acquisitions, which incentivises them to wait for further rate cuts.

We can expect an increase in M&A activity in 2024. Interest rates are the main drivers of the M&A market. The 50-bps rate cut from the Federal Reserve brings a positive signal to the markets and encourages M&A activity. This decision will bring the cost of capital down more for assets and acquisitions will start to look more attractive, bringing the deal volume up and driving deal sizes up. Furthermore, by looking at the supply side of capital, as the interest rate decreases, lenders are willing to provide more capital due to the decrease in the risk of being paid back. According to BCG, private equity firms hold 27,000 companies of which over 50% of them are held for over 4 years. Because PE funds have bought the companies at high valuations in the past, favourable market conditions are needed to generate a good ROI for its Limited Partners, but at the same time, PE funds have time obligations (between 3 to 6 years) to create a liquidity event. This shows that PE firms want to sell but are holding back to realise higher returns once the valuations are higher. To realise liquidity events, PE firms rely on continuation funds to be able to extend their ownership of portfolio companies, while respecting the obligation to its Limited Partners. We can expect though that there will be sell-offs of portfolio companies once the market conditions are better and valuations are driven up. Lastly, the world is still concerned with the uncertainty arising from the geopolitical tensions in the middle-east, Russia-Ukraine War, and US elections.

References

- Burges Salmon, “Guide to public takeovers in the UK”, 2023

0 Comments