Introduction

High levels of leverage have been common practice to increase returns since the genesis of the private equity industry, but as the industry evolves financial sponsors have come up with new and innovative ways to lever up not only their portfolio companies, but entire portfolios as well. This progression has led to what people now call the “web of debt” that private equity is entangled in. Beyond the leverage used in the initial buyout, sponsors have turned to dividend recapitalisations, PIK financing, NAV loans and subscription lines to further profit from the benefits of debt. However, with this comes the risks of an over levered balance sheet and exposure to bad credit for banks. This article aims to untangle the web of various debt instruments that private equity investors have developed in recent times in response to higher interest rates and a struggling economy.

How Does Private Equity Approach Leverage?

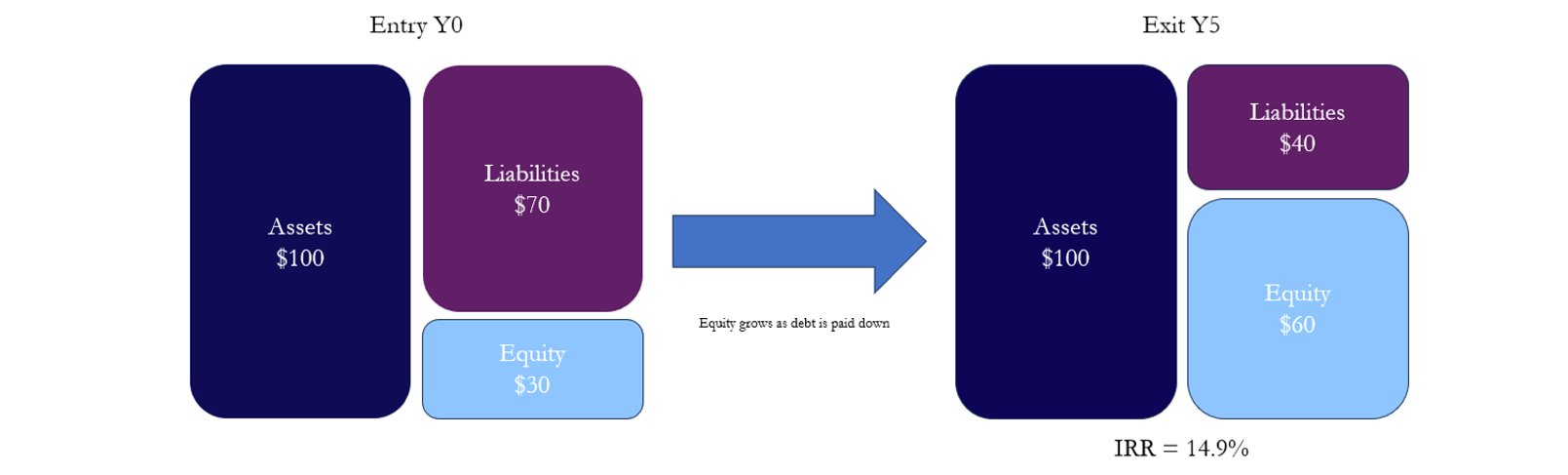

Private Equity firms utilize Leveraged Buyout (LBO) transactions in order to generate returns. One of the most utilized metrics used by financial sponsors to measure the successfulness of an investment is the IRR (Investment Rate of Return). Academically speaking, the IRR is the discount rate that makes the net present value of future cash flows equal to 0. The metric though has a more intuitive meaning, as it is also the expected annualised growth rate the investment is expected to achieve. There are 3 drivers of the IRR: leverage, operational improvements, and multiple expansion. By analysing these drivers, we can understand different tactics used by Private Equity firms. Firstly, operational improvements allow the company the PE fund to maximize the value of the assets of the portfolio company, which could for example have been mismanaged. By implementing improvements such as cost-cutting measures, organic growth, and enhancing synergies from add-on acquisitions, the value of the assets of the investment will grow due to higher cash flows, leading to a higher valuation. Secondly, a PE fund can acquire a company when it is under financial distress or under unfavourable market conditions, as it will be undervalued, expecting it to recover and then exit the investment at a higher multiple. Basing a strategy on this IRR driver though can be risky as it is entirely market driven and out of control of the managing fund. Lastly, the biggest driver in the PE landscape is leverage. By implementing debt, a PE firm can cut down the WACC of a company because debt is cheaper than sponsor’s equity. Afterwards, the PE firm by utilising the companies’ cash flows, will repay the debt growing their equity holding. All the drivers lead to substantial IRR, but the biggest one is leverage, which is the cause of such high utilisation of debt in LBO’s.

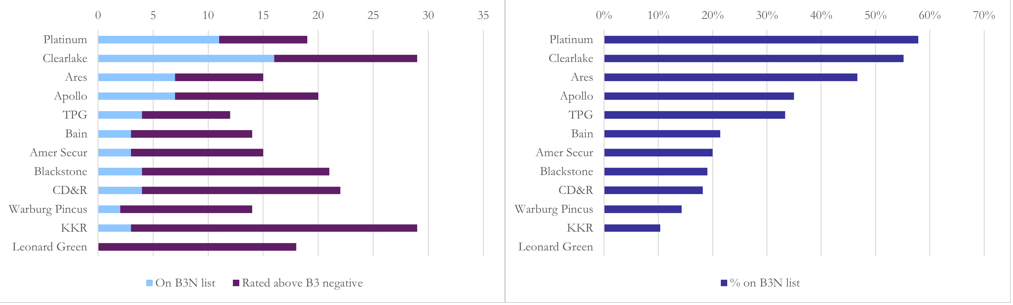

Each PE fund will have a set of strategies that they implement to generate returns for its investors. Some PE funds like Apollo, Ares and Clearlake will aim to acquire distressed companies at lower multiples due to the high risk of default. By providing liquidity to such companies and implementing effective management they try to de-lever the company and then exiting their investment at higher multiples, once the capital structure is stabilized. Although this type of strategy has the potential to generate high returns, it also will lead to high risk of defaulting, but sometimes even one successful investment can make up for many defaults. Other PE Funds aim to improve the operational efficiency of more established companies by implementing cost cutting measures, realizing synergies, and organic growth, leading to increased value and a profitable exit. As we can see a PE fund can be successful with both strategies if implemented effectively.

Evolution of leverage in the PE landscape

In the beginning Private Equity was a very controversial asset and received a lot of backlash as it was thought to be driven by financial speculations instead of intrinsic business value. Many questioned especially the amount of debt used to conduct an LBO and underlined the risks of an increase in interest rates and poor management decisions. Those concerns had solid grounds considering many transactions in the 1980s were financed by using 90% debt. One of the most popular cases were the acquisition of R. J. Ronald Nabisco Inc. (RJR) by Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. [NYSE: KKR] for $109 per share or $25bn. The acquisition of RJR was financed by utilising 87% debt. This acquisition has been the biggest LBO in the 20th century and has created one of the most important business books “Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco”. The case has rose some ethical questions regarding Wall Street’s practises as the LBO has left a reasonably healthy company with a high debt burden and has mostly benefitted insider traders. Further bankruptcies of companies such as TXU and Caesar’s Palace [NASDAQ: CZR] have underlined the risks associated with high leverage. High debt burdens will be very sensitive to decreases in EBITDA. When that happens, the interest coverage ratios decreases, and net leverage increases, leading to a weaker credit profile. This will bring the prices of companies’ bonds down in the secondary market, making it harder to refinance the outstanding liabilities, which can lead to bankruptcies and restructuring. Currently, leverage ratios have stabilized towards the 60% to 80% range in 2023 due to the higher cost of capitals and inflationary pressures, which lead to the decrease of interest coverage ratios, making debt harder to access. Furthermore, risks associated to debt in the modern PE industry have been given more weight, making transactions financed with 90% debt only history.

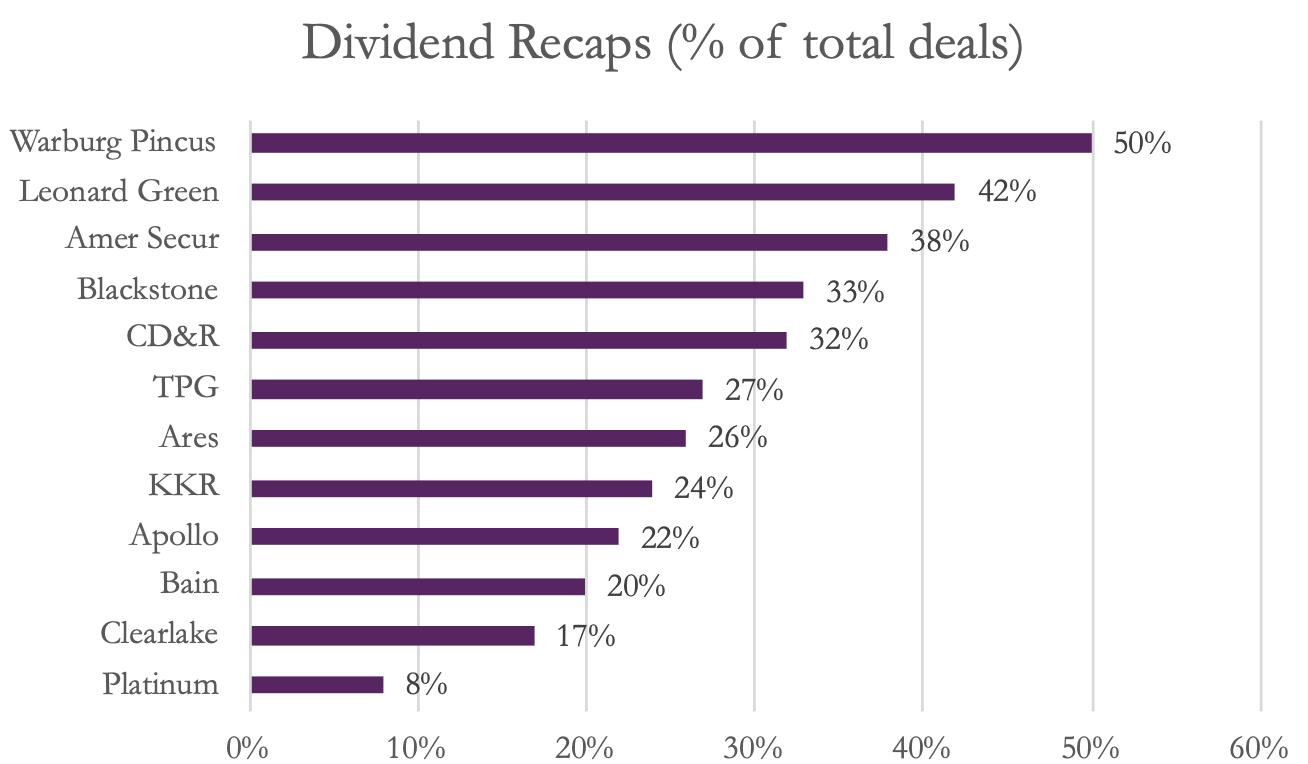

A liquidity event is the ultimate goal of a PE fund when entering an investment as the initial investors want ultimately to receive their money back in a reasonable time. This can be selling the acquired company to another party, making a company public through an IPO, or even using a continuation fund in order to extend the mandate, while allowing investors to obtain some returns. Another strategy commonly implemented by PE funds are dividend recapitalisations, which is a way for PE firms to generate returns when an exit is very unfavourable. By extracting value from the acquired company and increasing leverage to levels even higher than at entry, PE funds distribute the acquired cash to the shareholders through dividends, realizing a sort of liquidity event without losing ownership of the company. In a time where valuations are low this has been a big occurrence as shown in the graph below.

As we can see, according to Moody’s findings, the leading PE funds heavily rely on dividend recaps, with Warburg Pincus and Leonard Green being the leaders in implementing the strategy, with as much as half of companies bought by Warburg Pincus issued debt-based dividends. Some companies owned by Warburg Pincus such as Internet Brands and INTRAFI even issued multiple dividend recaps.

Net Asset Value Loan

A PE firm will almost never hold one single company but a portfolio of them. Sometimes PE funds will have some successful investment and others will perform poorly. The Venture Capital world is an extreme case, where the returns obtained from one early-stage start-up can in many cases make up for many failed ones. Let’s say a PE fund acquires Company A. which has been a successful investment. The PE fund though has also acquired Company B, which due to unfavourable market conditions, cannot realise an exit and generate the expected returns for its Limited Partners. Furthermore, the interest coverage ratio is decreasing and there is a substantial risk of the company going under distress. Our PE fund would like to re-allocate some of the assets from the successful Company A to the troubled Company B, and it can do that through a Net Asset Value Loan (NAV loans). By putting both of the company’s net asset value as collateral, the PE fund can obtain debt and allocate it to the struggling Company B, allowing it to meet its obligations to its Limited Partners and manage its interest payments. The loan can be obtained as providing debt to a group of companies is less risky than to a single one. The interest in NAV loans spiked soon after the pandemic, when high interest rates and inflation drove down valuations, making exits unattractive, while pressuring highly leveraged companies. By resorting to NAV loans, the PE fund can keep alive struggling companies by leveraging others. The biggest critique of this type of strategy is that it implements leverage on assets that were already leveraged in order to acquire them. This spreads the risk on the whole fund’s operations and can potentially cause a total loss for its investors if the creditor decides to conduct a fire sale of assets in case of missing payments. Furthermore, by putting the whole fund’s portfolio as collateral, the benefits of diversification are reduced as the performances of each company will be related to each other.

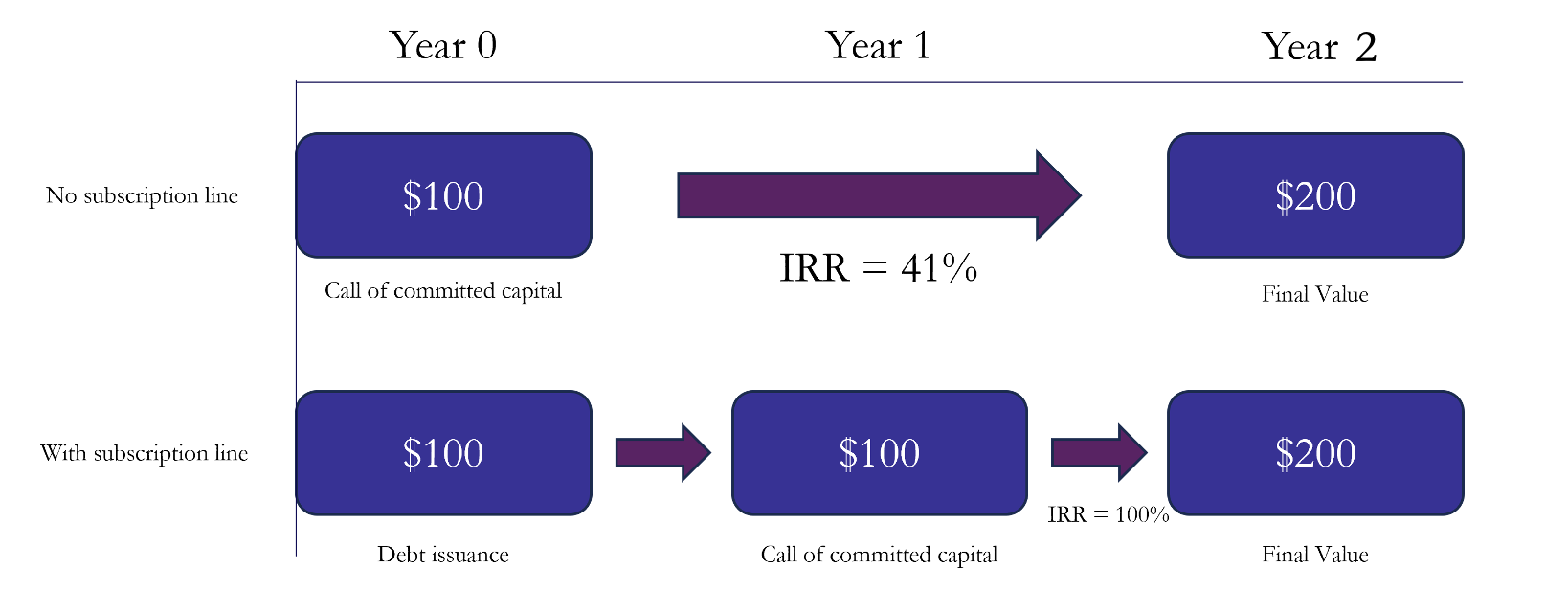

The last worth-noting strategy that is worth to mention are subscription lines of credit. This type of loan utilises a timing mismatch between the acquirement of a company, and the call of the committed capital. When a Limited Partner invests in a PE fund the allocated funds are called committed capital. A PE fund will not receive the total amount of the investment but only a part which is named “called capital”. The other part is called “uncalled capital” which is “called” by the PE fund when a deal is completed. What is interesting is that the PE fund doesn’t have to call the investment right after the acquisition but it can borrow cash to pay for the acquisition and call the investment afterwards. Although this gives flexibility when the funds aren’t immediately available, it also gives a lot of “wiggle room” for PE firms to inflate IRR, from which it is paid a management fee. This can bring many issues to the fund as it is utilising cash that will be utilised to acquire leveraged assets, as a collateral to obtain even more leverage.

How Are Sponsors Managing High Debt Levels

As a result of the effects of the pandemic, interest rates have been high, and the economy has been in a downturn ever since 2022 which has led to deteriorating credit ratings and bonds trading at a discount of the secondary market. This has made it increasingly harder to refinance debt which has led to an increase in distressed exchanges, defaults, and restructuring.

Private equity firms are notoriously known for having high levels of leverage, especially given their investment model of leveraged buyouts. (LBOs) This makes them particularly vulnerable to financial distress. One way in which private equity firms have been breaking out of this cycle is through distressed exchanges. A distressed exchange is an out-of-court alternative to Chapter 11 filings. It is a type of debt restructuring where the issuer offers creditors a new or restructured debt, or cash or assets, that amount to a diminished financial obligation compared to the original obligation which allows the issuer to avoid bankruptcy or a payment default.

As seen in Moody’s “Distressed Exchanges in Europe,” overleveraged companies, a large part of which include private equity firms, specifically in the telecommunications and cable sectors, have been using debt-for-equity swaps to help alleviate financial stress. These distressed exchanges, characterized as a form of default, have been on the rise. They were the most common default type across all PE-owned debt issuers between January 2022 and August 2024. This data strengthens the ongoing trend of private equity sponsors heavily favouring distressed exchanges as a debt restructuring tool, which helps them avoid an expensive bankruptcy process and preserve their equity.

Ultimately, distressed exchanges help sponsors maintain control of their portfolio companies, although data suggests that these companies typically end up in bankruptcy later anyways due to significant debt levels and trouble generating positive cash-flow post restructuring.

Private Equity firms have also turned to payment-in-kind financing to help conserve capital and manage high debt levels. Publicly traded private credit firms have reported the highest levels of income from PIK financing since data began being tracked in 2020 by rating agency, Moody’s. So, what is PIK financing? PIK financing is when interest payments come in the form of incremental debt added to existing principal and paid back at maturity, rather than with cash. This type of financing allows private equity firms to defer interest payments by issuing more debt instead of paying in cash, allowing them to maintain more flexibility in managing cash flows.

These types of loans do, however, have a catch: while in the short term PIK financing seems like a perfect solution to a company’s immediate cash pressure, it increases the firm’s debt load and overall financial risk. The deferred interest these companies take on compounds over time, making the process extremely expensive. Some high-profile companies, namely, Apollo-owned ClubCorp, Shutterfly, and CareerBuilder have all switched their existing cash-paying notes and loans into new PIK and PIK Toggle facilities, a type of loan that allows the borrower to decide between paying the interest in cash or choosing to “toggle” to PIK financing. In addition, recently, in April 2024, KKR-owned Global Medical Response, Inc., advised by Kirkland & Ellis LLP, issued 15% PIK preferred shares which they used to fully repay their second-lien term loan, reduce their term loan balance by $191 million, and add $99 million cash to their balance sheet. This PIK financing is expected to help them substantially improve free operating cash flow, making them more financially stable. These a just few examples that help highlight the growing prevalence and appeal for this type of financing in times of high interest rates.

Private equity firms have also resorted to Liability Management Exercises (LMEs), namely, dropdowns, uptiers, and double dips to help restructure their debt and improve their financial position without having to resort to default or bankruptcy.

“Drop-down” transactions are when valuable assets are removed from the collateral package to an unrestricted subsidiary, allowing the subsidiary to incur additional debt which is secured by the contributed assets. “Uptier” transactions are when new debt tranches with superior claims are created which subordinated an existing class of lenders. “Double dips” are where a creditor claims recovery on the same asset twice under different circumstances. The creditor is essentially “dipping” into two sources for repayment, increasing their chances of recovering fully compared to other creditors.

Through these various LMEs, distressed companies can encourage creditors to inject additional capital by offering them more appealing terms to help avoid a worse outcome like a default or bankruptcy. The distressed company will offer preferential treatment to those that contribute new funds and threaten significant losses for those that don’t contribute. Private equity firms have been using these LMEs to help manage the high levels of debt they are exposed to.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the private equity industry’s extensive use of leverage has evolved into a complex web of debt strategies that continue to reshape its landscape. While leverage remains a key driver of returns, the risks associated with high debt levels, especially in times of economic downturns and rising interest rates, cannot be overlooked. The recent developments of introducing leverage across the private equity industry have also re-introduced credit risk back into the financial system, with banks and other financial institutions facing a lot of exposure. Only time will tell us what new contraptions private equity investors will come up with in the coming years as they face more challenges.

0 Comments