Introduction

Bond markets across major economies-including France, Japan and the UK have undergone notable shifts in recent weeks as investors reassess fiscal uncertainty, inflation, rates trajectories, and political turmoil. While the recent election of new prime minister Sanae Takaichi in Japan is currently capturing markets participant’s attention, the ongoing fiscal and political chaos in the UK is a story that has caused major volatility in markets over the summer and still seems to be far from over. In this article we will take a closer look at what has and happened in the UK and provide an outlook for major events and factors that will potentially have a significant impact on markets in the near future. We will examine how Gilt markets have evolved since the 2022 crisis, take a look at the UK economy and dive deeper into the upcoming autumn budget in November — including our view on how we would position ourselves for these turbulent macro developments.

Recent Developments in the UK

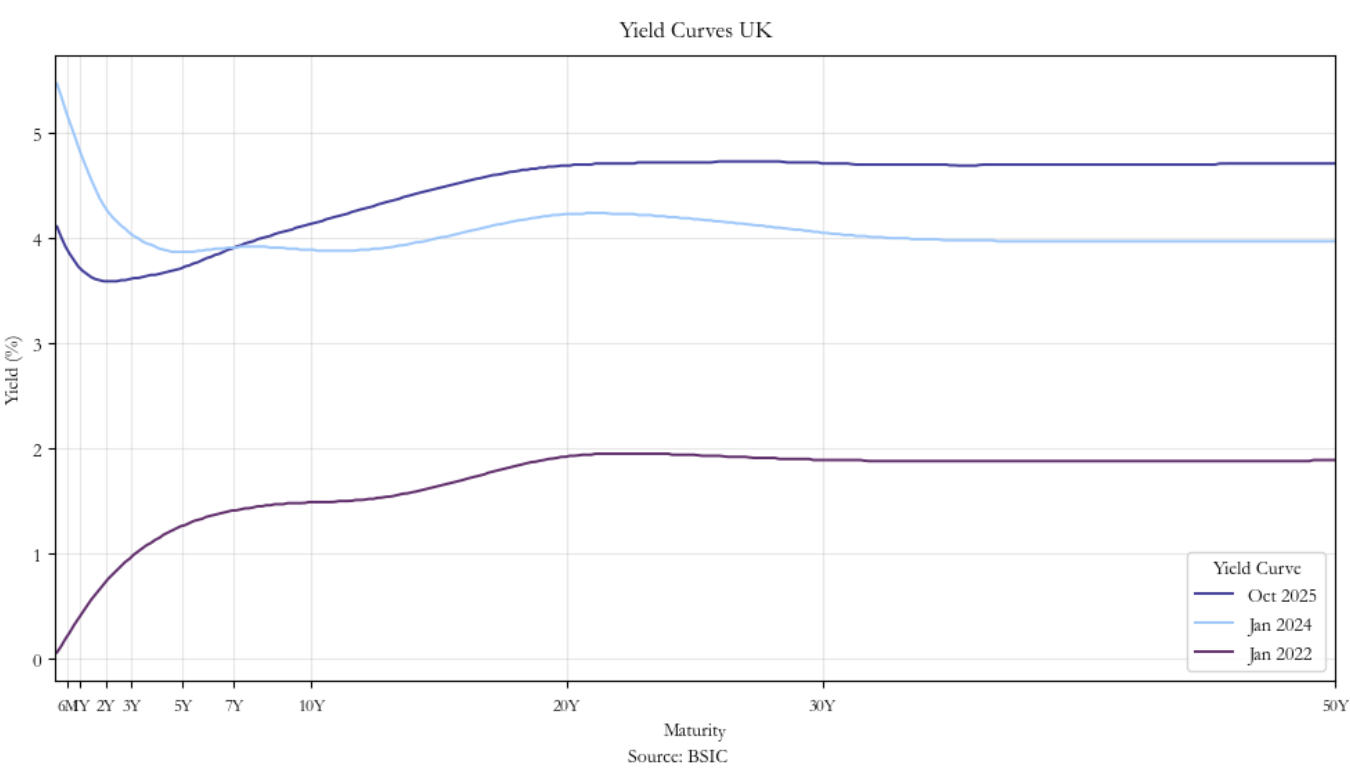

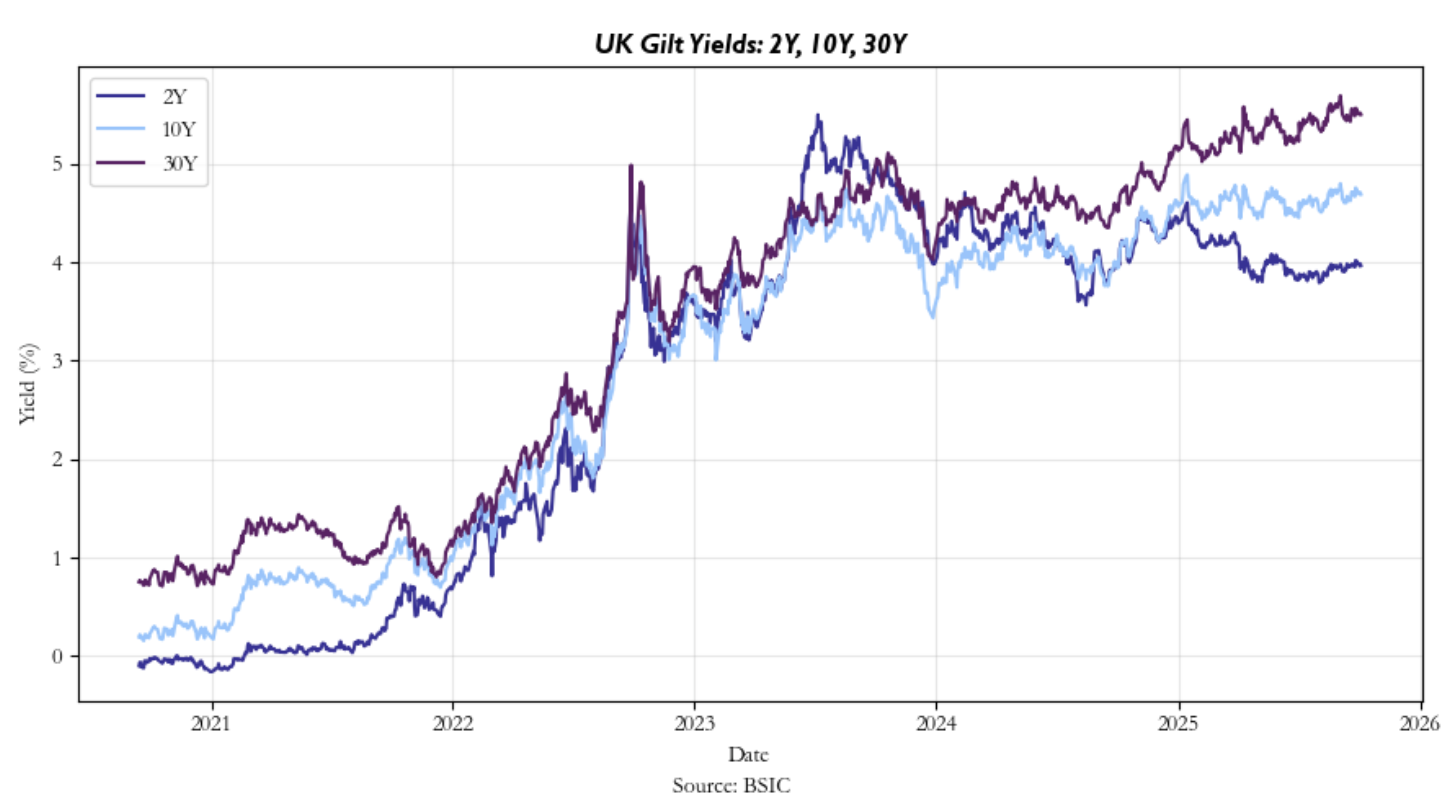

Before analyzing the current situation, we will take a step back and examine how the UK rates landscape has evolved over the past few years. While well known to market participants, we will start with the late events of 2022. Against a backdrop of surging inflation, slowing growth, and already elevated borrowing needs, Prime Minister Liz Truss introduced an unfunded tax-cutting “mini-budget.” UK bond markets were shaken as investors lost confidence in the UK’s fiscal credibility. The reaction was amplified by pension fund selling, and the 30-year gilt yield spiked above 5% — almost three percentage points higher than summer levels. After a series of policy U-turns and the appointment of a new government under Rishi Sunak, UK yields fell back and the immediate crisis abated, but the shock left investors acutely aware of Britain’s fiscal fragility.

In 2023, market focus shifted from fiscal credibility to inflation, which remained elevated from its 2022 highs. The Bank of England (BoE) responded with further aggressive monetary tightening, raising the policy rate from near-zero levels to 5.25%. The 2-year yield surged to about 4.9% in June — its highest level since July 2008 — as markets priced Bank Rate to approach 6% amid persistent wage and price pressures. However, toward the end of the year, global investors began demanding higher term premia for long-term bonds amid inflation uncertainty and widening fiscal deficits. As a result, long-dated UK yields climbed to multi-year highs: the 30-year yield reached ~5.1% in October 2023 (a 25-year high at the time), while 10-year yields neared 4.8%. Meanwhile, 2-year yields eased off their peak to the mid-4% range by Q4, as the BoE paused hikes at 5.25%. This movement was amplified by supply dynamics. Specifically, the UK Treasury planned to issue about £238 bn of gilts in FY2023/24, while the BoE was actively unwinding its balance sheet—selling around £10 bn per quarter instead of providing QE support—keeping upward pressure on yields.

Throughout 2024, inflation gradually eased, with headline CPI falling from 8.7% in April toward 3–4% by late 2024. A pivotal political shift also occurred, as a Labour government under Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Chancellor Rachel Reeves took office, pledging fiscal discipline but facing wary investors. At the start of the year, 2-year yields hovered around 4.5–4.8% and 10-year yields near 4.0–4.3%, leaving the curve inverted to flat as markets expected an eventual policy pivot but still demanded a premium for long-term debt. By mid-2024, disinflation became clearer, and the BoE cut rates for the first time in 15 years to 5.00%, prompting 2-year yields to drift down to around 4.2–4.3% by late summer, while 10-year yields held near 4.5%. The result was a nearly flat curve, with the 2s/10s spread close to zero, as markets balanced optimism about easing with caution over fiscal credibility. Later in the year, further BoE cuts to roughly 4.75% pulled short yields toward 4.0%, while 10- and 30-year yields remained stubbornly high around 4.5–4.8%. The curve therefore steepened modestly, turning slightly positive (around +30 to +50 bps).

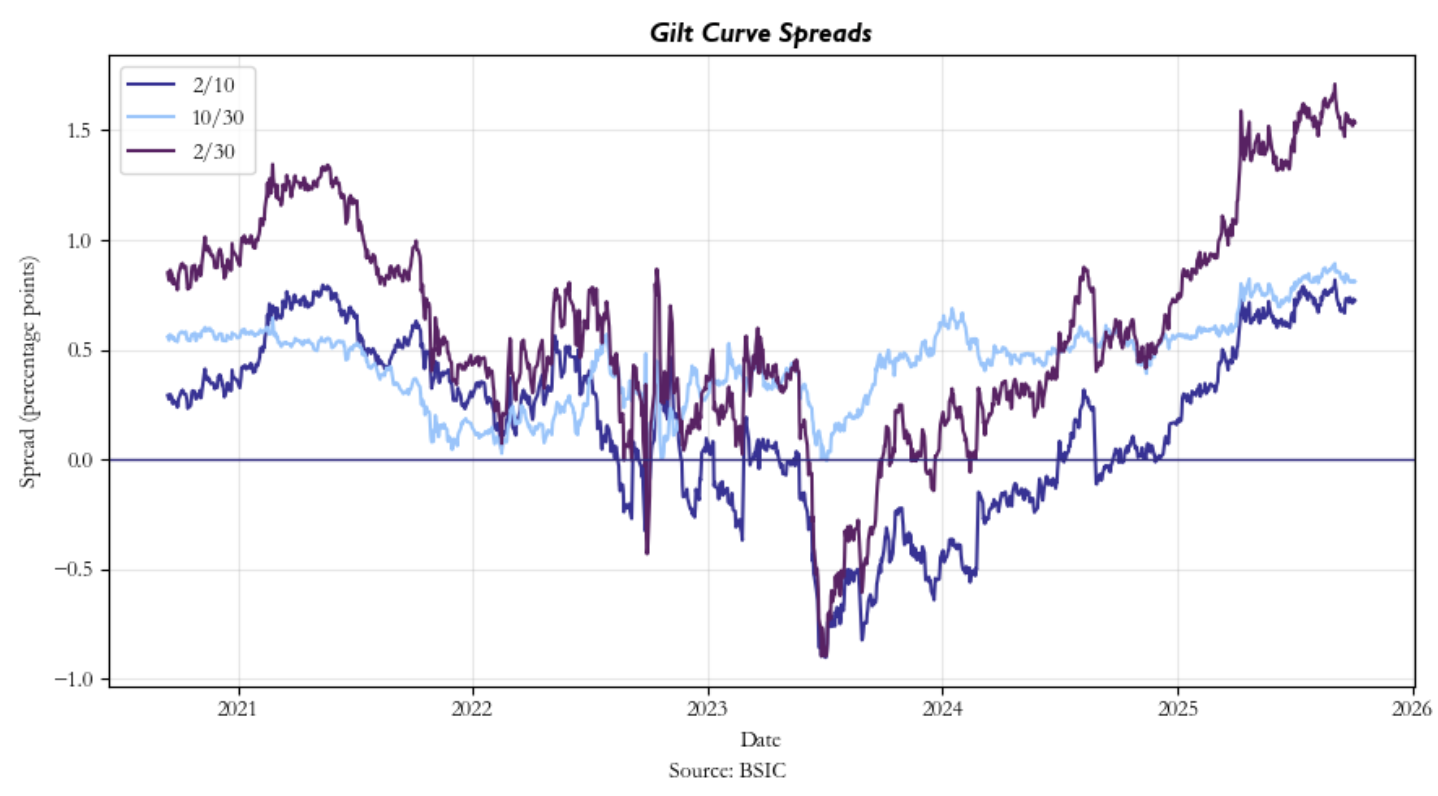

In 2025, renewed volatility and a dramatic reshaping of the yield curve characterized the UK rates market. The year opened with a sharp gilt sell-off, following a global bond rout and weak confidence in the new government’s fiscal direction. In March, the DMO announced a gilt issuance plan of £299.2 bn — below market consensus of ~£304 bn — prompting a brief rally. The 30-year yield fell by up to ~7 bps to ~5.32%, while the 10-year dropped by as much as 6 bps, ending ~2 bps lower at 4.74%. However, this reprieve proved short-lived. In April, U.S. tariff headlines triggered a global risk-off move and a sharp sell-off in long gilts: the 30-year yield spiked to 5.65%, the highest since 1998, while the BoE postponed a long-dated QT auction to ease market stress. The curve steepened sharply (2s near 4%, 10s ~4.8%, 30s mid-5s), underscoring investors’ demand for higher term premia. In July, another notable event shook the gilt market. Chancellor Reeves became visibly emotional during a speech, and after Prime Minister Starmer initially failed to back her publicly, 10-year yields jumped 22 bps to 4.68% — the biggest one-day move since the Truss episode — as markets priced in the possibility of her replacement by a less fiscally conservative chancellor. The following day, Starmer publicly reaffirmed his support for Reeves, gilts rallied, and the 10-year yield fell back toward ~4.5% as panic subsided. Notably, BlackRock, Schroders, and later Fidelity disclosed they had bought gilts into the sell-off, explicitly betting she would remain in government. Following the BoE’s August rate cut to 4%, the front end of the curve became anchored lower, while the long end remained sticky as traders priced in gradual easing alongside persistent supply and fiscal concerns. Overall, the UK yield curve experienced a historic steepening, visible in the chart below.

UK Economy

The British economy grew modestly in 2024, expanding by 1.1% after a weak 0.4% the year before, as high inflation and two years of rate hikes continued to weigh on economic activity. With the Bank of England starting to ease policy in the second half of 2024, growth picked up significantly in early 2025, GDP rose by 0.7% in Q1 and by 0.3% in Q2, broadly in line with expectations. More recently, economics growth’s momentum has faded: the composite PMI fell to 50.1 in September, down from 53.5 in August and the weakest in five months, as firms delayed hiring and investment ahead of the Budget, the unemployment rate sits at his highest level since 2021, at 4.7%. At the same time, the current-account deficit widened to £28.9 bn in Q2, or 3.8% of GDP, from 2.8% in the previous quarter, underscoring greater needs for government funding.

Public sector spending has remained high, total expenditure was estimated at 44.4% of GDP in 2024, only marginally lower than 44.7% in 2023 and still well above pre-pandemic norms of 40%. Borrowing reached £18.0bn in August 2025, the largest August shortfall in five years and £15.18bn higher than the month earlier, reflecting sticky spending and weaker than expected tax receipts. At end August 2025, debt was estimated at 96.4% of GDP, leaving limited fiscal space ahead of the Autumn Budget. Last year’s Budget increased taxation by £40 billions, but Reeves said she does not intend to repeat that magnitude, in line with the Labour party view. Even so, with growth still weakening, public finances under struggle, and the Spring spending review committing more to defence and to the NHS, the Chancellor will have to find new sources of revenue.

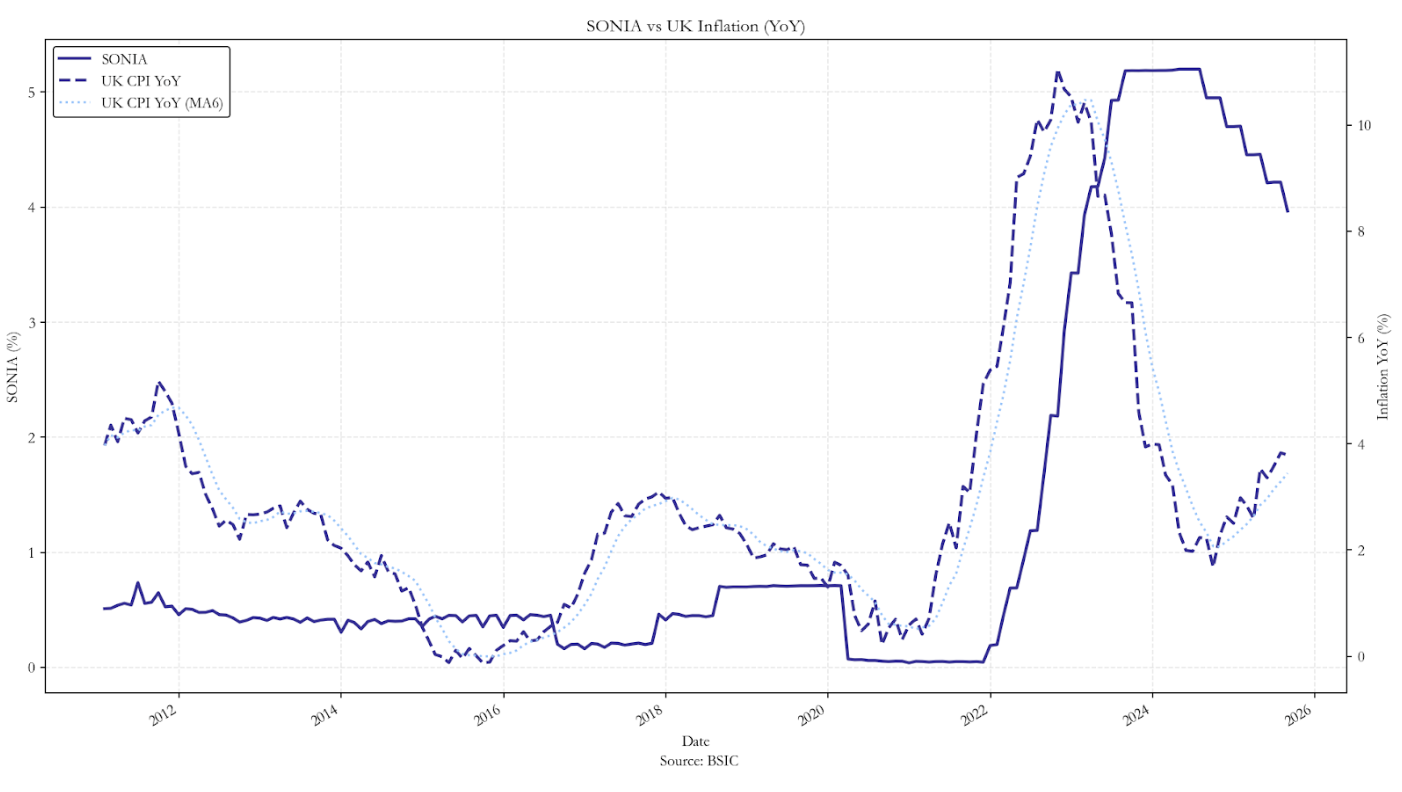

Over the last 15 months, the Bank of England has shifted from aggressive tightening to a more cautious easing stance, with interest rates are arguably being at the top end of what could be seen as the neutral rate, but still squeezing the economy. In 2024, Bank Rate peaked at 5.25%, where it remained for several months as the MPC battled persistent inflation. As the chart below shows, the SONIA rate itself reflects the actual level of short-term interest rates, and it can be observed that inflation picked up more strongly than anticipated after the easing policy and this rebound suggests that disinflation remains fragile and that policy may have loosened slightly ahead of underlying price dynamics. By August 2025, with headline CPI sitting at 3.8% YoY, still significantly more persistent than in other countries in the G7 with the OECD projecting to have the highest inflation in the G7 this year and the second highest in 2026, only behind the US, The BoE delivered the last cut of the cycle, lowering Bank Rate to 4.00%, and has since paused to assess the durability of disinflation. Markets had initially priced a faster easing path, but policymakers have repeatedly stressed that cuts will be gradual and reversible if inflation proves sticky. This could mean that yields on the front end of the curve could rise again, as they might have been mispriced. The BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee expects inflation to peak at around 4% in September, largely driven by a sharp pickup in food and energy costs, which rose by 5.1%, the fastest pace in 18 months and notably stronger than elsewhere in Europe. By comparison, headline inflation stands at just 2.0% in the euro area, 2.1% in Germany, 1.6% in Italy, and 0.8% in France.

Markets are currently expecting that the interest rate easing cycle will most likely not continue until the start of 2026, with Overnight Interest Rate Swaps (OIS) pricing in only a ~25% change of another rate cut this year. The main reason is that inflation remains persistent, and also has further upside risks which we will discuss later on.

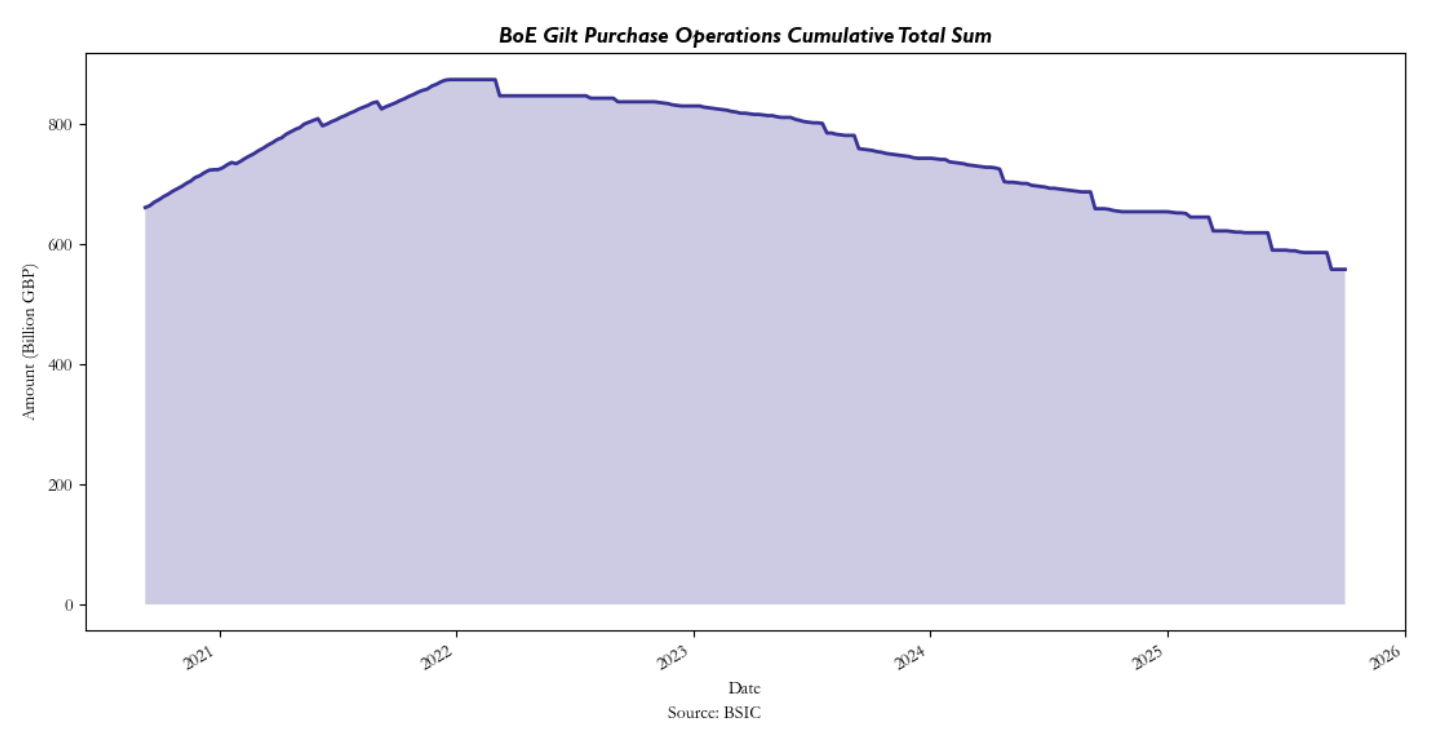

The BoE is alone among major central banks in conducting outright sales of the government bonds it bought to boost the economy in the years after the 2008 global financial crisis, rather than just letting them mature.rather than just letting them mature. Especially during the covid pandemic, the BoE conducted massive quantitative easing programmes, with cumulative Gilt holdings peaking at £875 bn in 2022. Since then, the BoE has reduced its gilt holdings from £875 bn pounds to 558 bn pounds, and for the past two years it has offloaded gilts at a pace of 100 bn pounds a year, the fastest among other major economies. Although the central bank views the pace of quantitative tightening as having little impact on the wider economy, it is closely watched by financial markets, where some blame it for pushing up British government borrowing costs, especially at the long end of the curve, where a lot of the quantitative tightening operations are being conducted. Actual data signals that the gilt yields spreads 2s10s and 5s30s have gone up since the start of QT, even though the relationship between the two events is heavily influenced by other factors. On the 18th of September, the MPC reduced the annual target for quantitative tightening from £100 bn to £70 bn. This marked the first major slowdown in QT since the programme began in 2022. Because the BoE’s gilt holdings are concentrated in medium and long dated maturities, the adjustment primarily affects the long end of the curve. This move shows how serious the increase in long term borrowing costs has become, but also that the government began to realize how serious this issue has become and created the incentive to relieve some pressure from the long end of the curve.

Autumn Budget

The main event investors are currently awaiting is the Autumn Budget decision, taking place on the 26th of November this year. In the past, Rachel Reeves promised that her parliament won’t borrow to fund day-to-day public spending by the government and wanted to get government debt falling as a share of national income by the end of this parliament. However, the margin at which Reeves is operating is getting thinner as borrowing keeps increasing. Back in March, the OBR already signalled that the chancellor only had a £10bn buffer left to meet her self-set rules. Now, Bloomberg Economics estimates that Reeves must finance a £35bn budget cap, further raising the question of which measures she will use to raise this money.

Given the recent increase in government borrowing and the growing worries about the UK’s fiscal situation over the past year, the government has been forced to reconsider its plans—rethinking tax increases and cancelling planned benefit cuts that were originally supposed to save billions in public spending.

With the fiscal outlook worsening and pressures on Gilt markets rising, Reeves recently hinted at possible tax rises at a Labour Party conference in Liverpool. Although Reeves stated that the election promise not to increase the main tax rates still stands, it becomes increasingly likely that the government will have to raise taxes in order to fund spending, with the UK’s debt bill predicted to reach £111bn this year, while also trying to control upward inflation risks. Starmer and Reeves could argue that US tariffs and the increased need for defence spending leave them with little choice. Either way, in our opinion the Labour Party has to break either the promise of turning around the economy and the long-term fiscal situation, or the tax promise made to voters. However, most investors currently expect further fiscal tightening at the November Budget. We believe that, in the end, Reeves will have to find measures that won’t lead to additional government spending and renewed worries among bond vigilantes, as the bond market is essential for enabling Labour to also satisfy its voters through support for industry, social care, and economic revival.

An important step towards this would be to fill the funding gap through tax measures instead of relying only on borrowing. Potential tax raises include extending the freeze on current income tax thresholds, which is due to end in 2028 and is often referred to as a stealth tax. This would mean that as salaries rise over time, more people would reach an income level at which they start paying tax or qualify for higher rates. This package could also include cutting 2 points from the employee National Insurance rate while simultaneously adding the same amount to income tax. Groups such as pensioners, landlords, and the self-employed would be affected the most by such a move, as they don’t pay that rate of National Insurance. In addition, reports suggest that the government might replace stamp duty, leading to landlords paying more in taxes. Another policy currently attracting market participants’ interest is the unpopular two-child benefit cap. The policy, introduced by the Conservatives, prevents households on universal or child tax credit from receiving payments for a third or subsequent child born after April 2017. While the cap is highly unpopular, lifting it would create an additional £3.5bn funding need that the government would have to cover, according to asset manager RBC BlueBay. Sir Keir Starmer has previously spoken of his desire to ditch the two-child cap when economic conditions allow, without specifying exact circumstances, making it questionable whether November is the right time for such a change.

Implications for UK Rates Markets

We believe that most investors are currently exhibiting rather low confidence in Reeves to deliver credible fiscal tightening at the Autumn Budget, pricing in a lot of risk in the rates markets, especially at the long end of the UK yield curve, preparing for further fiscal loosening that could outweigh the financing of the funding gap through tax hikes. However, given the recent turmoil in the Gilt markets and the fact that 2Y/10Y, 2Y/30Y, and 10Y/30Y spreads are all sitting at historic levels, in our opinion, it is highly unlikely that Reeves and the Labour Party parliament will decide to stress bond markets even more—particularly the long end of the yield curve.

At a recent Labour Party conference in Liverpool, Reeves already hinted at tax rises, saying that the government is facing difficult choices and that she would not take risks with the public finances. Furthermore, the BoE’s decision to dial back its quantitative tightening bond-selling programme from £100bn to £70bn to curb rising bond yields signalled that the serious worries about UK government borrowing—and particularly the rising long end of the yield curve—are also concerning the government itself, which fears that borrowing costs will continue to rise.

In our view, Chancellor Reeves has no other choice but to significantly raise taxes in the next Autumn Budget if she wants to avoid putting additional stress on debt markets. As investors are still pricing in a lot of risk at the long end of the yield curve, tax increases at the Budget will likely signal that there remains a degree of fiscal discipline within the current UK government, relieving some pressure on the long end of the curve.

Furthermore, inflation worries in the UK are unlikely to ease significantly soon, given weak productivity growth and rising wages. Some of the policy measures in the Autumn Budget might also put additional pressure on inflation, making it more difficult for the government to bring the rate of price increases down to the 2% target soon. For example, tax increases on businesses will likely be passed on to consumers, making it difficult to reduce consumer prices in the short term. In our view, a potential scenario set out by the BoE in its Monetary Policy Report in August appears more probable than its main forecast, which sees inflation returning to target by mid-2027.

To express this view on upcoming fiscal and economic developments in the UK, we believe that a duration-weighted flattener trade between the 10-year and 30-year maturities of the Gilt curve would be optimal to capture our view on the autumn budget and near-term fiscal developments, especially persistent inflation and increased funding through tax rises. Since there is a long-dated Gilt auction on the 21st of October, with cover ratios having been quite volatile in recent auctions, we would enter this trade in November to reduce the exposure to independent factors and high market volatility prior to the budget, in order to avoid unnecessary moves in the position.

References

[1] Goodman, Philip, “Bank of England slows pace of QT and tilts away from long-dated gilt sales”, 2025

[2] Giles, Chris, “Truss’s mini-budget leaves lasting scars on UK’s fiscal credibility”, 2023

[3] BlackRock — “Fixed Income Outlook (UK)”, 2025

[4] Kumhof, Michael & Salgado-Moreno, Mauricio, “Quantitative easing and quantitative tightening” (2024)

[5] Giles, Chris, “Rachel Reeves faces rising pressure over UK’s fiscal credibility”, 2025

[6] Office for Budget Responsibility, “Economic and Fiscal Outlook”, 2025

0 Comments