Introduction

Since its initial birth in medieval ages, and its formal establishment in the 20th century, in the past fifty Islamic finance has seen tremendous growth. In recent times Shari’ah-compliant bonds have been issued to many countries worldwide, including Nigeria, United Kingdom, and Malaysia. Nowadays, the Maldives are experiencing critical times, with the countries’ net foreign exchange currency reserves running low and is facing serious repercussions.

In this article we aim to provide the reader with an overview of Islamic Finance and the principles it relies upon, concentrating on the Sukuk market and history, before analysing the Maldivian macro-economic scenario upon what could be the first government to default on Shari’ah-compliant debt in history. Lastly, we will conclude by presenting a standard Sukuk pricing model.

Islamic Finance overview

Islamic finance, also known as Shari’ah-compliant finance, refers to banking, lending, and saving practices that follow the guidelines defined in the Shari’ah, the Islamic legal code which has its roots in the Quran. Islamic finance follows two key principles: profits and losses are shared among all parties involved in the transaction, and neither lenders nor investors are allowed to collect or pay interest. Furthermore, Islamic finance prohibits investments which involve goods or activities prohibited by the Quran, such as alcohol and gambling, and bans usury (known as “riba“), speculation (known as “maisir“) and deception (known as “gharar”). Another crucial element of Shari’ah laws is known as “zakat”, which serves a wealth distribution mechanism, and can be interpreted as a property tax. To avoid any misinterpretations and supervise financial activities, Islamic banks often include a Sharia Supervisory Board (SSB), that certifies that all investments and transactions are Shari’ah-compliant.

Since Shari’ah law prohibits interest payments and risk-sharing is a pillar stone of Shari’ah-compliant finance, investors earn profits through equity participation. Borrowers repay the loan without any interest, offering instead investors a share of the profits generated by the assets or businesses in which the loans are funneled. Therefore, if the loan does not yield a profit, neither the investor nor the borrower benefits from the transaction.

All forms of financing are based on profit and loss sharing mechanism, regardless of which party (if not both) provides the capital and is appointed to management roles. On the equities side, both in public and private markets, Islamic finance allows investments as long as the company isn’t involved in any prohibited activity, such as lending money for interest; fixed income instruments are also allowed, however, not in the conventional form of a bond. Instead, Islamic finance relies on sukuk’s, bond-like instruments that entitle the lender to a share of profits. For this reason, the loan must be invested in a tangible asset.

The outlook for the Sukuk market looks bright: Sukuk’s have spread significantly in the past decade and don’t seem to slow down. There are various factors that suggest that demand for these securities will continue to rise: first, various regulatory bodies, such as the Islamic Financial Services Board (ISFB), are working toward a standardization of Shari-ah law interpretation and Sukuk structure; secondly, they are creating clearer guidelines to safeguard investor’s rights in case of default. Another element that will likely spur Sukuk issuance, in times of heightened ESG awareness, is the introduction of sustainability-linked Sukuk’s, with Green and Social Sukuk’s becoming more and more popular.

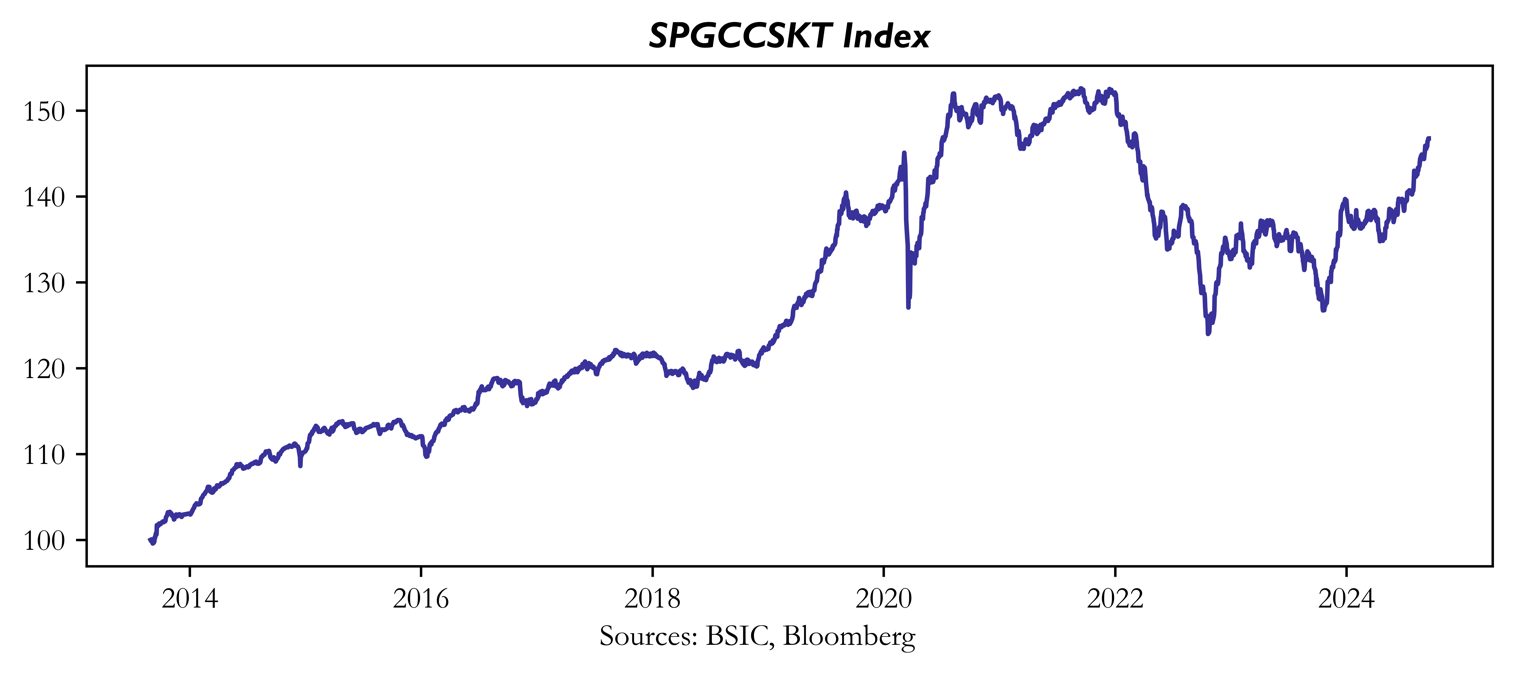

In the graph above we have the reported the S&P GCC bond and sukuk index, which tracks the performance of sharia-compliant securities issued by governments or corporations in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), such as United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait and Oman. The index has risen around 47% in the past ten years, signaling tremendous growth as these types of securities gain more and more popularity: major slowdowns have only occurred in 2020 due to the pandemic and in between the end of 2022 and 2023, when the FED hiked rates to above the 5% mark and geopolitical instability threatened the area.

Sukuk structure and pricing

In this section we will explore the mechanics and structure of sukuks to understand how they differ from standard corporate and government bonds. As a starting point, it is important to note that contrary to the notion of lenders and borrowers in standard debt contracts, in sukuk markets we deal with sukuk issuers and investors under Islamic contracts. In a sukuk issuance, the issuer will usually securitise an asset and investors will subscribe and get a certificate that represents ownership in the underlying assets, its cash flows and risks. At maturity, investors will receive the value of the sukuk, which will depend on the future value of the securitised asset. As a final definition given by the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (2007) “sukuks are certificates of equal values representing undivided shares in ownership of tangible assets, usufruct and services or in the ownership of the assets of particular projects or investment activity”.

Even though not bonds per se, sukuks are engineered financial products that give rise to bond-like cash flows to investors while adhering to Shari’ah principles by switching the interest payments for business-type financial contracts. We will now focus on introducing some specific sukuk structures, all of which start with the problem of identifying the Shari’ah compliant assets:

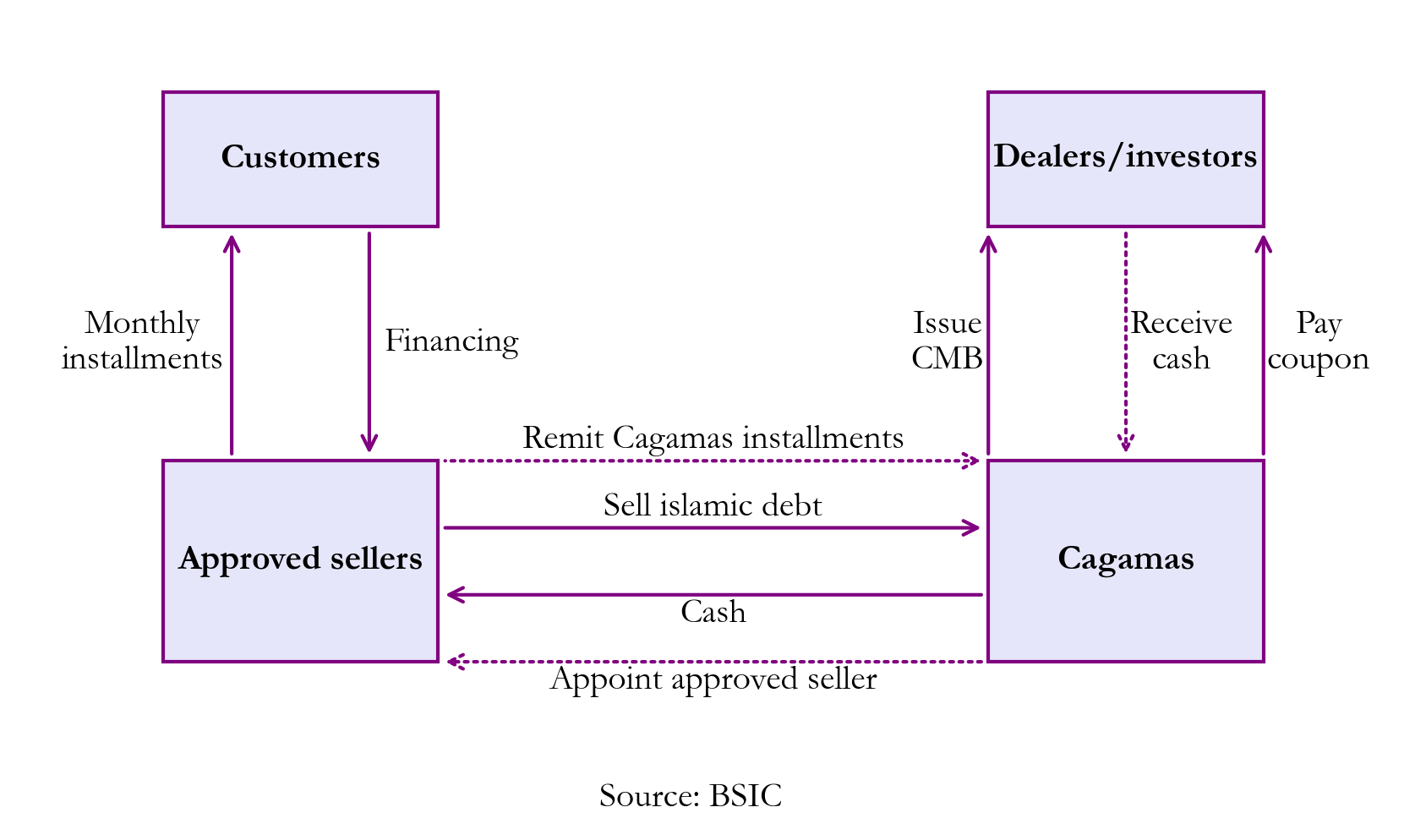

- Mudharabah sukuk: here the first term means “partnership based on trust” and essentially the contract is between a provider of capital (robbul-mal) that receives the certificate and a party in charge of a project (mudarib) who issues the certificate. To illustrate these types of securities we will focus on Cagamas Mudharabah Bonds (CMB) introduced in 1994 in the Islamic housing financing market. In this contract, the cagamas and the sukuk holder share the profits according to a profit share ration established in the contract. The actual mechanics of how this works are shown in the diagram below.

These securities are priced according to the following formula ![]() , where P is the price in cents, C the coupon for the period, E is the number of days in the current coupon period, r the yield, T the time from the transaction to the next coupon payment date, t the time to the final value date, FV the face value.

, where P is the price in cents, C the coupon for the period, E is the number of days in the current coupon period, r the yield, T the time from the transaction to the next coupon payment date, t the time to the final value date, FV the face value.

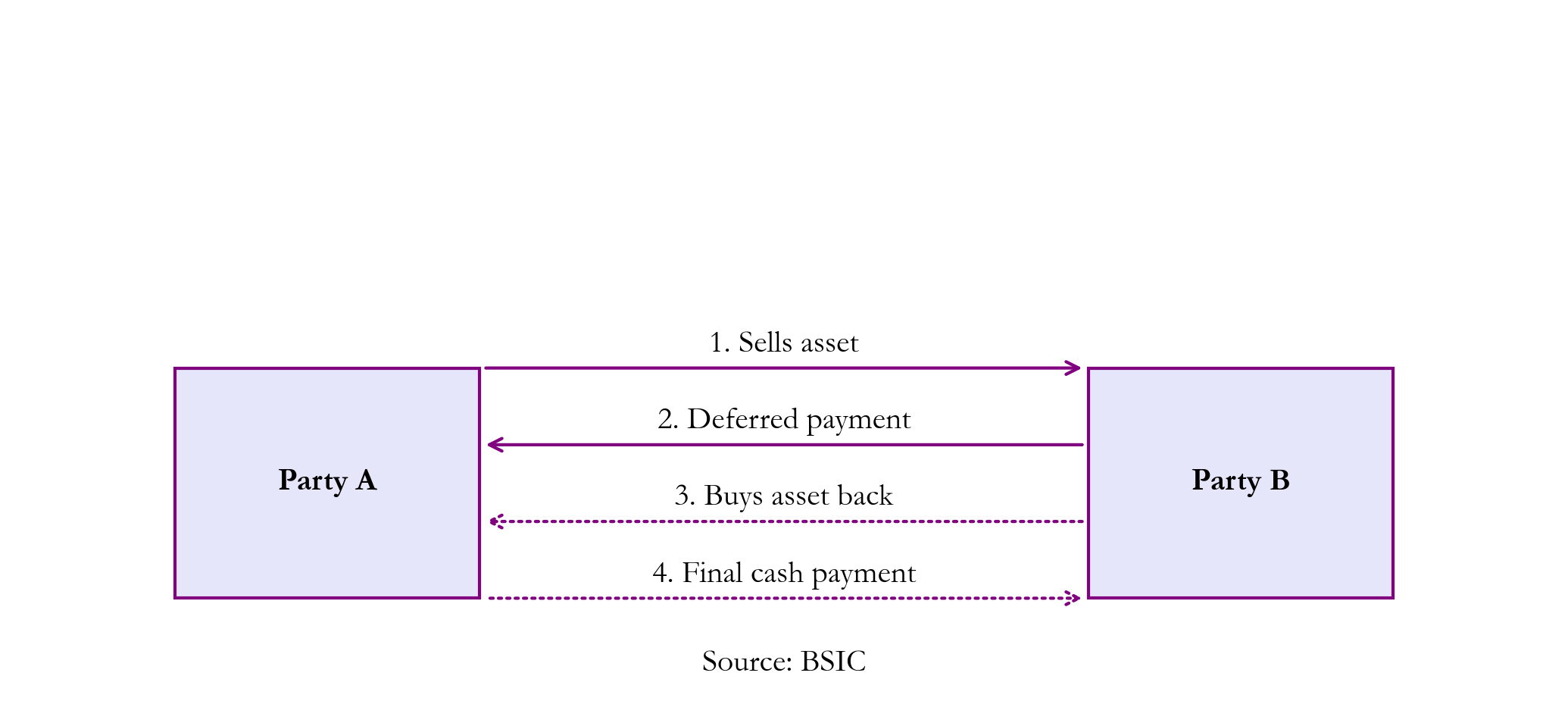

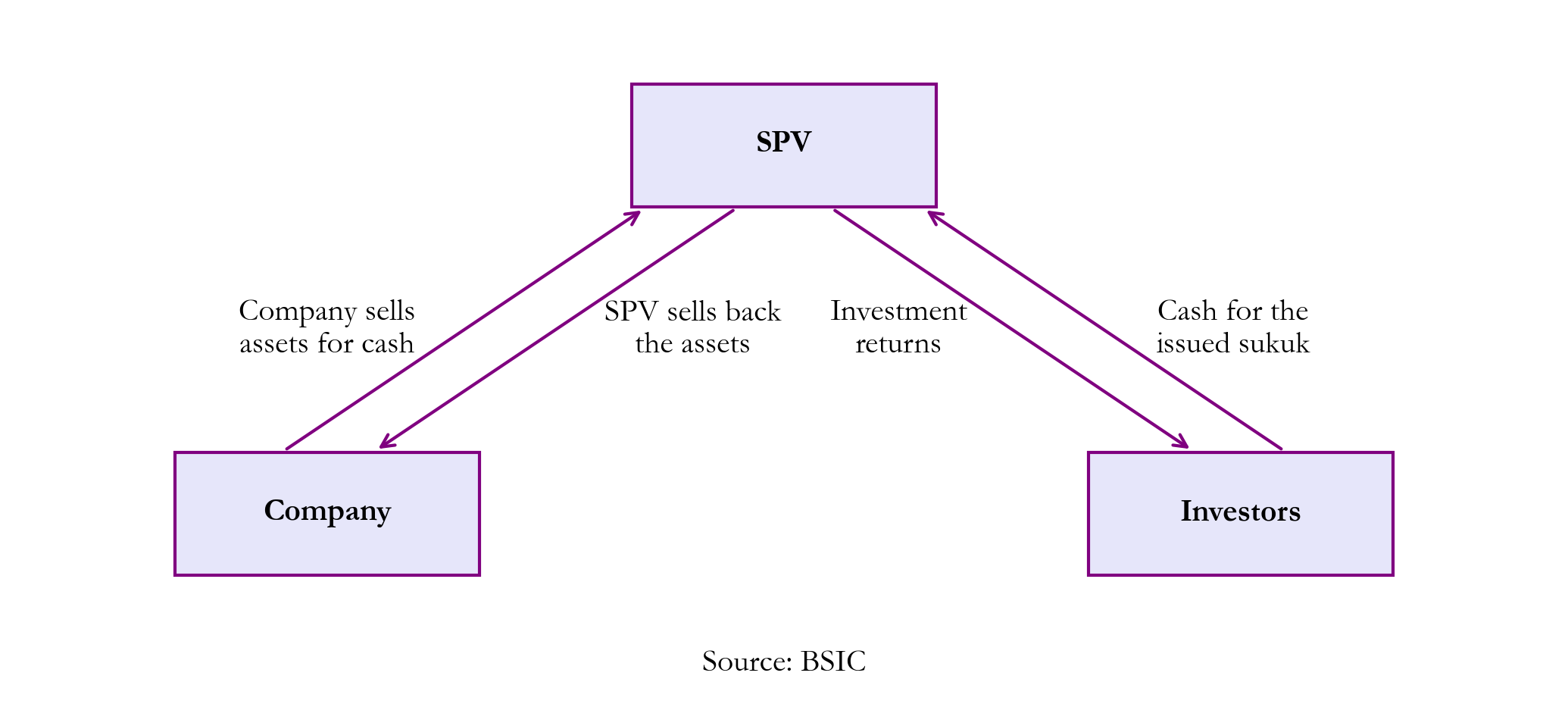

- Bank Negara Monetary Notes (BNMN-i) sukuk: this type of security is based on the concept of bay al-inah that is very close to a repo transaction, in which a party sells an asset and buys it back according to the structure shown in the following diagram. These types of securities were introduced by Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) to manage liquidity.

The whole process starts from BNM identifying the compliant asset and selling it to dealers on a discount basis, then buying it back at par value at maturity and once this debt is created the BNMN-I note will be issued to investors. To price these instruments the standard discounting formula is used as follows: ![]() . From a historical point of view, these securities experienced ups and downs as the bay al-inah principle caused many arguments among Islamic scholars as it is seen as a mean to obtain cash without any commercial reason.

. From a historical point of view, these securities experienced ups and downs as the bay al-inah principle caused many arguments among Islamic scholars as it is seen as a mean to obtain cash without any commercial reason.

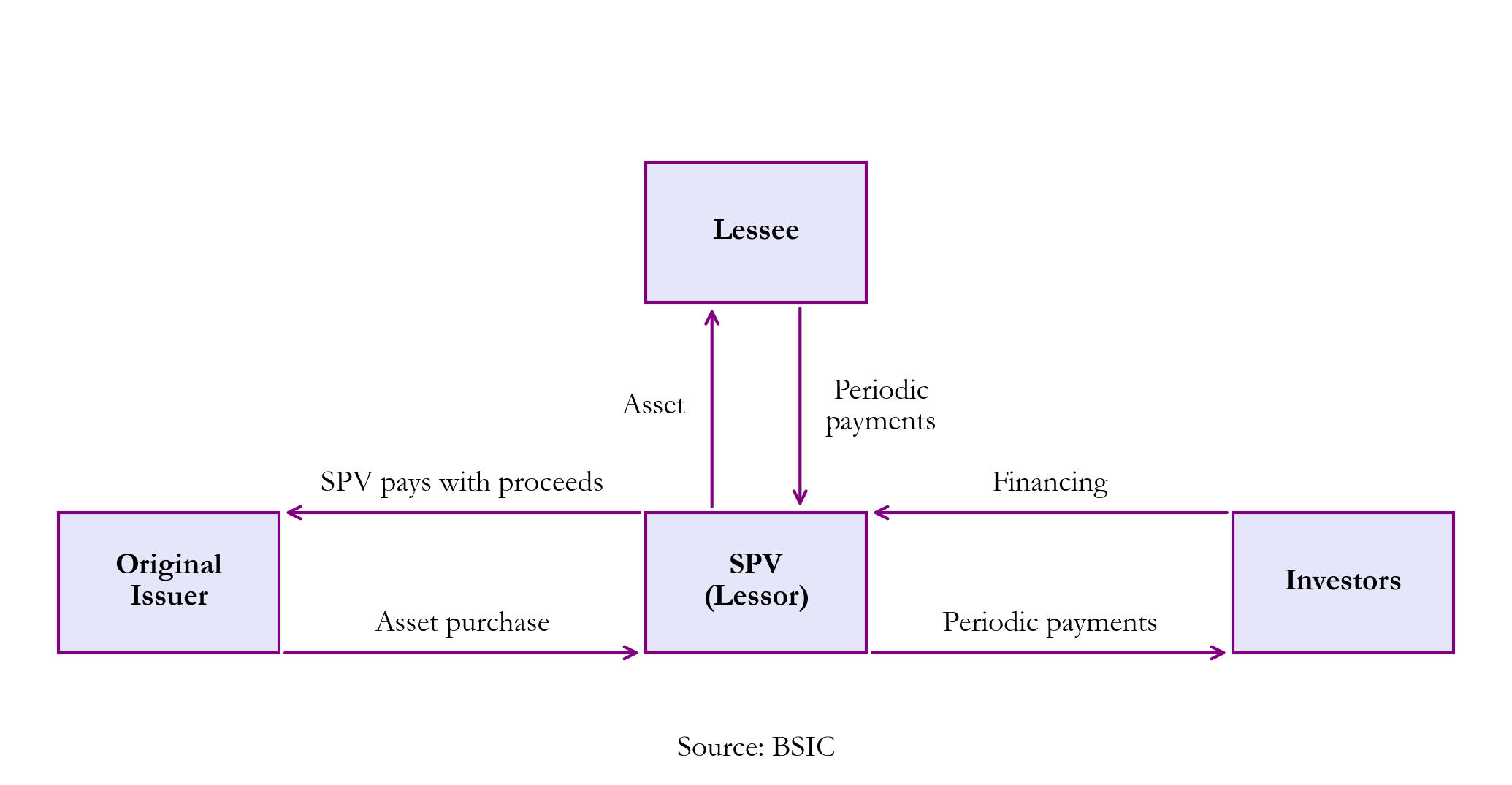

- Al-ijara sukuk: these are rental contracts very similar to standard leases and are one of the most significant Islamic bonds in the market. A typical example is house financing in which the bank buys a house for the customer and leases it until the customer paid the full value at which point ownership is transferred. The typical structure is shown in the following diagram.

In these transactions, the SPV will usually profit from the difference in periodic payments received form the lessee and the periodic payments made to the sukuk holders. The pricing of these instruments will be composed of both the present value of periodic payments and the final expected sale price of the asset once the contract is over. Al-ijara sukuks are among the most widely accepted instruments as they are based on the principle of ijarah mutahiyah bi al-tamlik (rental ending with sale).

- Government Investment Issues (GII): several contractual types fall under the scope of government issues: bay al-inah, qard hassan (benevolent loans) and bay al-dayn (sale of debt). The third type of contract involves the sale of one party’s payable obligations and has been debated for a long time among scholars. Most securities involve a combination of bay al-inah and bay al-dayn as the first step involves the creation of a securitised debt according to a bay al-inah transaction that will then be traded according to a bay al-dayn transaction. Since according to Islamic finance principles, the government debt must not be interest-bearing the transactions are structured as follows: the government will sell to financial institutions Shari’ah compliant assets for immediate cash payment and pay out coupons plus a deferred payment to buy back the asset according to the maturity of the contract. The main issue with this type of instruments is that when they land on the secondary markets, they are traded by markets participants for quick profit-taking and not held to maturity as Islamic principles would dictate.

- Murabaha sukuk: this is a cost-plus profit sale-based Islamic bond, it is a contract in which disclosure of both original price and the markup applied is required. The name comes from the word ribh that means increase and the increase (profit) must be disclosed by the seller and has to come from one of the following methods in order to be allowed: 1. bay al-musawamah (bargaining sale) here the price is established through a negotiation; 2. bay al-amanah (trust-based sale) here the seller discloses their buying price and the buyer proposes a fair price at which they are willing to buy (by essentially providing a “fair” bid-ask spread to the seller). The first (and most intuitive) type of such instrument is based on a bay al-inah transaction as it involves the buying and selling at a markup of the same asset between parties structured as shown below.

Another possible structure is the so-called tawarruq transaction, here there are intermediaries acting as wakeel on behalf of the issuer, essentially the assets (usually commodities) are bought and sold to brokers and not directly by the parties as shown below.

- Al-wakalah sukuk: this last type of contract is an agency-based bond based on the principle of wakalah here a principal will appoint a wakeel to act on their behalf and invest their fund in a pool of investments or Shari’ah compliant assets. The wakeel will provide its expertise to achieve a given rate of return within a specified period of time. The principal is usually structured as an SPV and uses the returns from the investments to give periodic payments to the investors and use the surplus to pay performance fees to the wakeel. At maturity the wakeel will liquidate the investments of the SPV and return the funds to the principal that will in turn return money to the investors. This structure is very similar to the murabaha structure except for the lack of pre-arranged profit ratio. Finally, at maturity, the SPV or the obligor will exercise the final options that depend on the contractual agreement and dissolve the trust by returning the dissolution amount to investors. The typical structure is reported in the following chart.

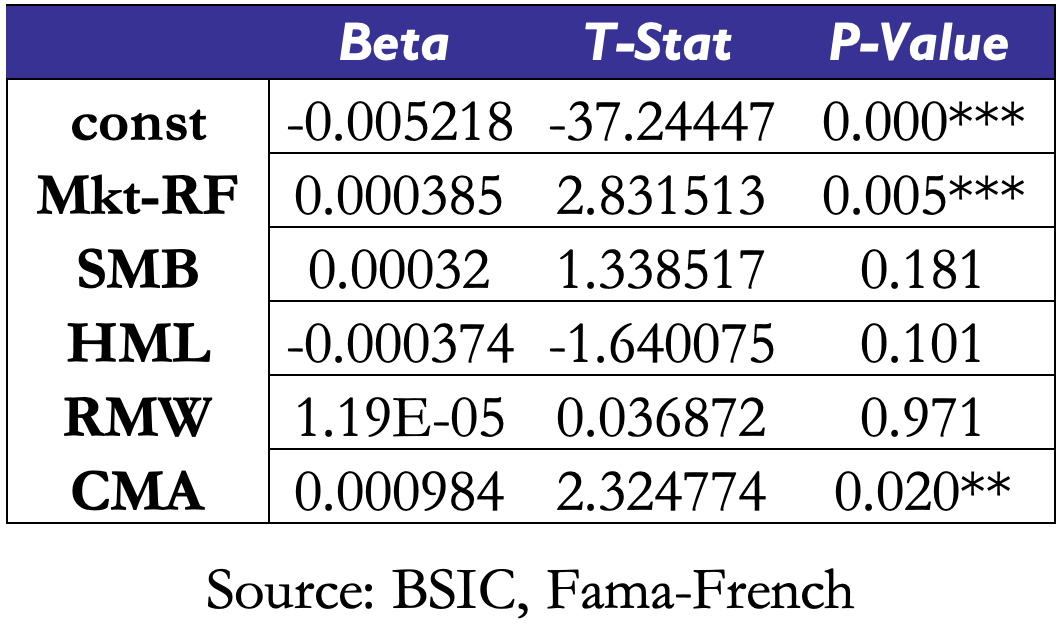

From a pricing perspective, a common issue is the absence of a reference rate due to disagreement between the issuers and the fundamental inconsistency of using an interbank rate to price Islamic bonds that due to their nature cannot pay interest and therefore their pricing should reflect other risk factors. Uddin et al. [6] propose a 2-factor pricing model based on the sukuk market risk factor and informational asymmetry risk factor work well for sukuks irrespective of their contractual structure. The rationale behind the inclusion of the information asymmetry factor is that returns can be driven by generally unknown causes like the risk of the securities becoming not Shari’ah compliant and if their movement is not largely driven by the overall market. In fact, this “Shari’ah risk” is not priceable by standard risk factors and is focus on new research in Islamic finance. Nevertheless, market risk seems to be significantly priced in the overall performance of sukuks as shown by the Fama-French regression ran on the SPGCCSKT index as shown here.

In the charts below we have highlighted the number of issuances and respective yield by rating in the limited dataset provided by the Emirates Islamic Bank. By comparing the Sukuk’s yields across all ratings with the ICE BofA US Corporate Index Effective Yield it emerges than some major discrepancies arise between the two when it comes to lower ratings, specifically from a Ba3 to a Caa3 rating: corporate bonds offer a 5.43% yield on Ba3 and Ba3 bonds, approximately a 6.57% yield on B1 and B2 bonds and a 12.01% yield on Caa1 and Caa3 bonds. This confirms the thesis presented in “Islamic Bonds Ratings and the Price of Risk” by Khoo and Klein, which suggests that Sukuk’s offer lower yield than traditional corporate bonds although a more thorough empirical analysis would be necessary to obtain more definitive answers.

In the previous analysis we refer to Moody’s ratings as it’s the agency that rated most bonds in the available sample due to the agency’s rating model specific to Islamic financial instruments that considers the specific asset-dependence of the securities and the contractual structure of each bond.

Inside the Maldivian crisis

The Maldives are facing critical times after the country’s foreign exchange reserves fell to compromising level in the past months as the country is facing a $25mln payment in October on its outstanding sukuk worth approximately $500mln. The idyllic archipelago is burdened by sovereign debt: the country relies heavily on imports, and due to global inflation and highly expensive infrastructure projects, government debt has risen significantly. In the month of August reserves amounted to about $437mln ($500mln in May), well below the government external debt service of $557mln in 2025 and $1bln in 2026, which alone is insufficient to cover two months’ worth of imports. Important reasons that have led to the economic crisis have been the diplomatic frictions with India in 2023, when newly elected Maldivian president Mohamed Muizzu rose to power campaigning about strengthening ties with China and gaining more independence from the countries’ closest neighbour. This has brought to a series of problematics, including Indian tourists boycotting the archipelago.

Fitch Ratings has downgraded Maldivian sovereign debt twice in the last two months, furtherly increasing default concerns, after the value of the outstanding sukuk dropped to 68 cents on the dollar. To further worsen the outlook for investors, seizing Maldivian assets comes with its own set of problems: due to the nature of sukuk’s, capital is directed to the purchase of tangible assets which are later sold to a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) and then leased back by the sukuk’s issuer, with the lease being directed to investors as payment. The Maldives use a Cayman Island-based SPV and in the past have referred to the countries’ $140mln hospital as underlying asset, complicating potential claims investors may make.

With the Maldives now looking for capital inflow, both China and India have expressed interest in offering aid, given the strategic positioning of the Maldives and the opportunity of strengthening influence in the Indian Ocean. The Maldives seem to have found an agreement with India, consisting in a $400mln exchange currency swap, and the possibility of a seeking long-term loans from a $800mln line of credit extended to the government in 2019. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has established a currency swap window for countries in the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), which can access up to $2 billion in dollars or euros to help prevent payment crises. A foreign currency swap consists in a swap of interest payments (in some cases it may involve the principal as well) between a loan in one currency (Maldivian Rufiyaa) and a loan in another currency (Indian Rupee), aimed at securing foreign currency at favourable terms.

References

- Ahmed et al., “Islamic sukuk: pricing mechanism and rating”, 2014

- Financial Times, “Maldives hunt for bailout to avoid first Islamic sovereign debt default”, September 2024

- Khoo and Klein, “Islamic Bonds Ratings and the Price of Risk”, 2023

- Razak et al., “The contracts, structures and pricing mechanisms of sukuk: A critical assessment”, 2018

- Reuters, “China throws fresh support line to crisis-threatened Maldives”, September 2024

- The Economic Times, “India ready to give Maldives aid as sukuk default risk looms”, September 2024

- Uddin et al., “Why do Sukuks (Islamic Bonds) need a different pricing model?”, 2018

0 Comments