Introduction

In the past year Berkshire Hathaway slowly built a 5% stake in each of the 5 most important trading houses in Japan. The overall size of the transaction is ¥670bn ($6.3bn) and it was backed by a surprising ¥625.5 billion issuance of yen-denominated bonds made in September 2019. What is even more interesting is the timing of the acquisition, as usual, contrarian to the trend of fleeing the Japanese stock market after the resignation of Shizo Abe. Some analysts speculate that this move might be on the forefront of a move of the Asset management industry from the arguably overvalued US equity markets toward an heavily discounted Japanese. However, there are caveats to this thesis and this investment might still just be one of the typical “against-the-main-stream” kinds of Warren Buffet bets.

Trading Houses 101

A trading house is an intermediary used by manufacturers to foster trade abroad. It consists in a group of businesses that import and export products, facilitating transactions between the home country and foreign countries. It offers an array of services – it could act as an agent for the manufacturer in the foreign market or as an intermediary that would ease the import-export process through local connections.

Trading houses have quite a few advantages – they make use of scale economies when placing large orders at discounts, have a wide network worldwide that helps attract new customers, and have developed effective currency risk management techniques due to their constant involvement in international trade. They are attractive for retailers to trade goods through because they provide expertise in international markets, discounted rates, and save any currency exchange complications. At times, they could even offer small businesses access to vendor financing through direct loans and trade credits.

To provide an example, imagine Trading House A buys coffee wholesale from Brazil and then sells it to a UK retailer at a slightly higher price to cover its costs and earn profit. The retailer has an incentive to buy the coffee through the trading house to avoid handling the importing process on his/her own, thus saving considerable time from potential interactions with numerous wholesalers.

Unique presence in Japan – The Sogo Shosha

Trading companies are typical for Japan for historical and economic reasons. Due to the country’s small-scale territory and limited range of resources, it must import a significant amount of goods to keep its economy intact. Nowadays, it does so mainly through its big trading houses, locally known as “Sogo Shosha”. To name a few, the largest and most notable ones are Itochu, Marubeni, Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Sumitomo (the ‘big five’).

These corporations are suppliers/wholesalers/distributors that operate within the whole value chain, from natural resources (upstream) to consumer goods (downstream) and everything in between (midstream). Unlike in other countries where trading houses are specialized in a specific industry, the Japanese ones are extremely diversified, offering goods & services ranging from food to chemical plants to aerospace and oil exploration.

As the name in Japanese implies (総合商社 = “to combine a wide range of functions, goods, and services into one commercial enterprise”), we can perceive the “Sogo Shosha” as diversified trading conglomerates.

an important term to mention here is ‘keiretsu’ – a set of various companies that have developed close relationships and sometimes take small equity stakes in one another, with each one operating independently from the others. Keiretsus adopt either a horizontal or a vertical integration business model, depending on whether they want to form an alliance between companies from different sectors or to include the different segments of the value chain within one sector (manufacturers, suppliers, and distributors). A central component of their business is a bank that provides financing for all the involved companies within the network. Keiretsus have been dominating the Japanese economy ever since the end of World War II when their previous form (the so-called ‘zaibatsu-s’) was dismantled. In fact, Sogo Shoshas are naturally a key component of the keiretsu environment, providing trade services both to fulfill the needs of the core business of its keiretsu, car manufacturing in the case of Mitsubishi, and to serve a great variety of other secondary businesses. However, this seamless integration in the Japanese industrial system creates a lot of complexity in terms of the business model and in terms of governance, because they have so many different stakeholders that have a saying in the governance decisions as per Japanese practice. This complexity has fended off foreign investors for a long time because it is usually extremely hard to know exactly what one is buying with a complex web of cross ownerships and alliances.

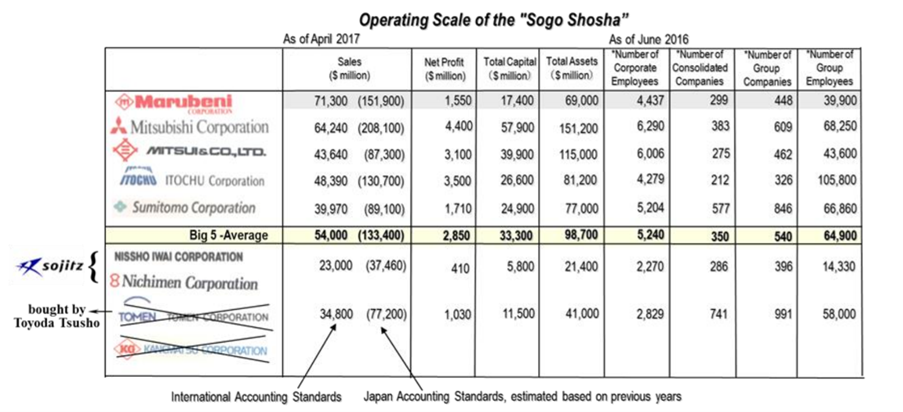

Now let us focus back to the trading house business again. To have an idea about the operating scale of a typical Sogo Shosha, a table with information on company characteristics, such as sales volume and number of companies and employees within a group, can be seen below:

Source: Marubeni Corp. Research Institute

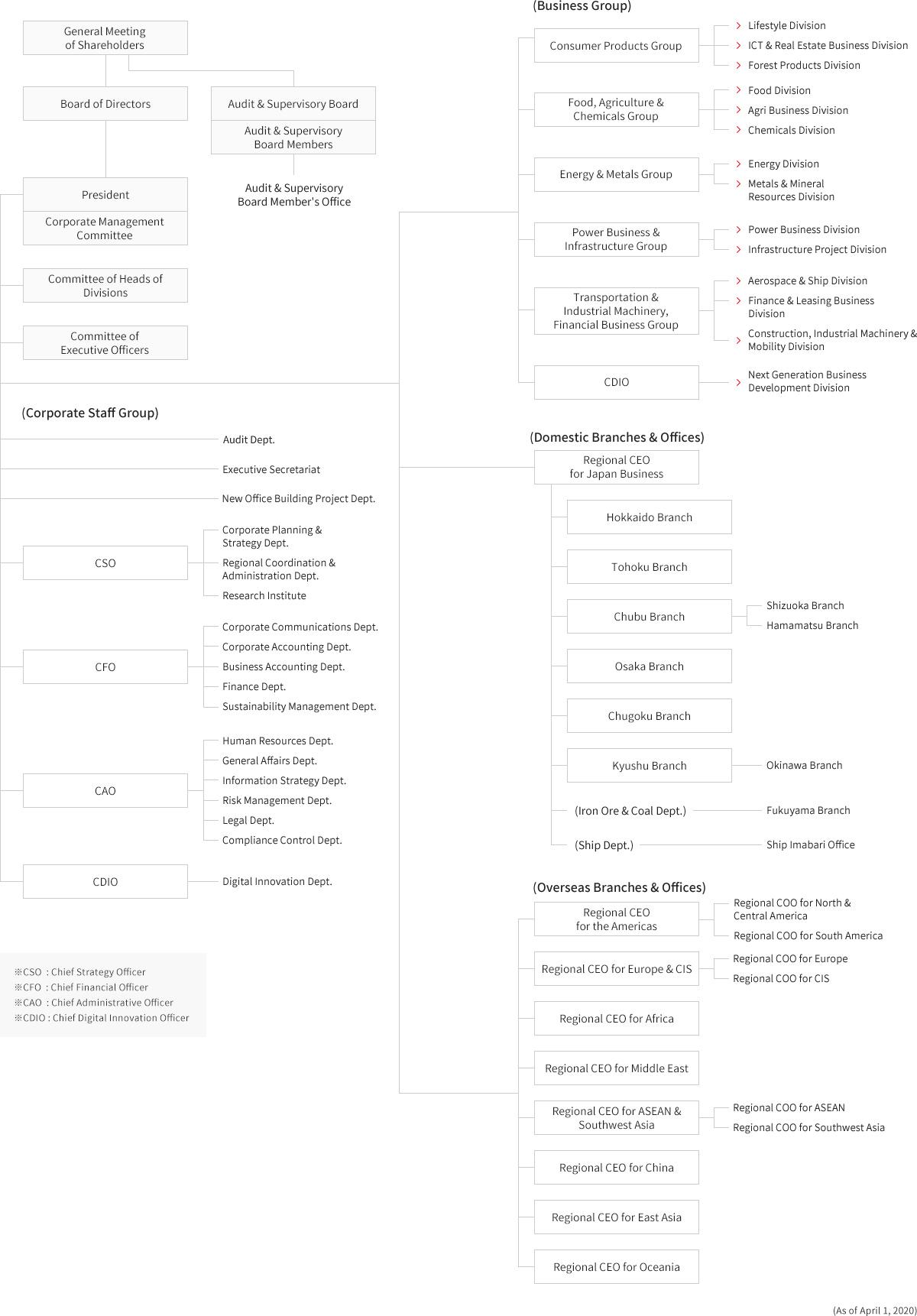

Sogo Shosha’s business model is unique to Japan and the world – a shosha can handle tens of thousands of different items/products in diverse industries through an array of subsidiary and affiliate companies within a global network. Simply put, the business is divided by industry (example below, Marubeni Corp. business areas) and by division. Each division may start/acquire a company or form a joint venture anywhere in the world to fit the group’s strategic purposes.

Source: Marubeni Corp. website

Apart from being excellent intermediaries, shoshas have also mastered the supplementary activities related to their core operations – logistics, risk management, coordination of large-scale projects, and finance. Regarding finance, they provide loans and debt guarantees to their customers to advance and foster trade, project financing for large-scale projects, and invest in certain core businesses to gain greater certainty at parts within the value chain. The integration of these functions is a key distinguishing feature of Japanese trading houses.

In short, the fundamental aim of a Sogo Shosha is to fully integrate the supply chain of any product it includes in its group, by being involved in as many stages as it could. Since each product has its own value chain, a Sogo Shosha’s chain consists of tens of thousands of mini-value chains, united under the name of the mother company – the Shosha (Marubeni, Mitsubishi, Itochu, etc.).

Japan’s economy and culture

Since the early 1990s when Japan’s real estate and stock market bubble burst, the country has experienced sluggish economic growth. Less than 20 years later, the global financial crisis shook the entire world economy. In 2010 Japan’s government budget deficit-to-GDP ratio exceeded 200% and less than a year after, in March 2011, a catastrophic earthquake and tsunami struck northeastern Japan. Indisputably, Japanese economy was in need of a stimulus to escape from this pattern of long-term sluggish growth and overcome the consequences of past events. Unfortunately, the growth expectations at that time were so disappointing and the expectations of change in prices were getting worse and worse, they resulted in creation of deflationary pressure. With help came Shinzo Abe in December 2012, when the Liberal Democratic Party won a general election, making him the prime minister. He introduced the set of economic policies, known as “Abenomics”, with 3 most important objectives: fiscal consolidation, more aggressive monetary easing and structural reforms to boost Japan’s competitiveness and economic growth and finally get out of the deflationary spiral. The optimistic perception of these was visible as soon as the beginning of 2013, when a staggering 22% rise in the Tokyo Stock Price Index (Topix) was observed compared to the previous year. The policies have been felt in the international arena as well. As a reaction to the strategically weakened yen, the largest net exporters such as Germany and China raised concerns about a possible global currency war and a game of reciprocal competitive devaluations. With Trump voicing the same concerns and advocating the opposite of the multilateral negotiations favored by President Barack Obama, the alliance between Japan and the US was even called in question by some analysts.

Nevertheless, during the year that followed the introduction of Abenomics, foreign investors became big net buyers of Japanese stocks, driving their holdings from 24% to 28% of Japanese overall number of shares in 2015. However, recently the proportion came back to levels from 2012, especially after Y485bn worth of Japanese stocks was sold, in net terms, in the last week of June 2020 by foreign investors. According to Mizuho strategist Masatoshi Kikuchi, US investors in particular “tend to regard the market as a collection of microcaps that relies too heavily on old-economy firms”. Among the reasons why foreign investors might feel discouraged from holding Japanese shares is the record-breaking number of shareholder proposals presented during this year’s annual shareholder meetings. This might be perceived by foreigners as an encouraging sign of activist momentum and therefore raise concerns about potential threat of ‘‘hostile’ activism. Secondly, the recent proceedings of Japanese railway companies buying shares in one another act as one of the market’s greatest turn-offs. While this is perfectly in line with japanese keiretsu, it makes business practices look collusive in the eyes of foreign investors not accustomed to such practises. Lastly, a good part of Japanese stocks are subsidiaries of other listed companies and 12.7% have a corporate shareholder that owns more than a third of the outstanding shares. Once again, it is a typical case of keiretsu, however, from where foreign investors stand, it is putting Japan right next to Russia and Brazil for lack of corporate governance transparency and excessive complexity, which does not give a good impression about Japan’s market.

Shinzo Abe resigned from his position in September 2020, however, his successor, Yoshihide Suga, promised to continue the policies and goals of the Abe administration, including the Abenomics. However, analysts are pointing out that one of the key reasons why Abe’s reforms were successful was the political stability which he introduced as the prime minister. With him being in the office for almost 8 years compared to an average of 17 months for his postwar predecessors, he ensured that policies introduced have been much more likely to be completed. What is more, he was able to compel the cautious and conservative Japanese bureaucratic state to experiment with new and much needed economic policies. On the other hand, not all the predefined goals were achieved within those 8 years, with inflation still remaining well below the 2% target being just one of them. Japanese nation might perceive this as a failure of the whole program and hence not be so eager to accept a new version of it.

Investment thesis

Whenever Warren Buffet suddenly makes an investment there is a good chance, based on its indisputable track record, that there is money to be made there. Indeed, with the US equity market being at record heights in spite of the covid-19 pandemic, it is natural for a well versed value investor to look for markets where Price-to-book ratios are lower for structural reasons. Japan, however, might have good reasons to have low valuations as the economic outlook of the country is becoming increasingly more bleak after all the positive results of Abenomics were struck by coronavirus and the credibility of its government, after the resignation of Shinzo Abe, is put under scrutiny. Furthermore, the previously mentioned complexity of Japanese corporate structure, centered around the Keiretsu model, makes these companies really unconventional and unattractive investments to fund managers that do not have the time and insights to carry out the necessary due diligence. This goes against the “easy to understand” principle that even Warren Buffet claimed to follow for its entire career. Finally, focusing more on the trading house business itself, it is very reliant on commodities’ prices and thus can prove to be fairly volatile and particularly affected by the dismantling of the global supply chain occurring in the past months.

It is therefore easy to see that there might be good reasons why the Price-to-book of the 5 Sogo Shoshas is equal or lower to one and that their stock performance might be worse than the Japanese market itself. So what exactly did Warren Buffet see in this opportunity?

First off, Warren does not believe in the common definition of risk as the volatility of the stock over a period of time. Instead, he claims that an investor should look and what is the potential loss he/she might incur into and balance it with the potential upside. In this case we have steadily profitable businesses that have a 4% dividend yield and that are essential to the functioning of the Japanese economy. Indeed, in the early 2000s they were called “dinosaurs” and the consensus was that e-commerce would have disrupted the industry, but exactly the contrary happened and trading houses evolved to serve exactly the needs that a more interconnected economy had. Therefore, buying at depressed prices these companies that are so well integrated and necessary the downside is minimal, while on the other hand in the long run these businesses will pick up again traction as international commerce goes back to the previous level.

Secondly, these trading houses are becoming so much more than just an intermediary, but they evolved to provide trade financing, make direct investment in the form of debt or equity in strategic companies, making Joint Ventures to promote international commerce in strategic products. This dynamic and lively way of doing business is so far off the idea of “dinosaurs” that used to describe these companies and offers incredible opportunities to create synergies and exploit a rebound in international trade as the global supply chain is redesigned. This network of relationships and private investments is exactly what Warren Buffet is trying to leverage as the Berkshire Hathaway press release states: “The five major trading companies have many joint ventures throughout the world and are likely to have more of these partnerships. I hope that in the future there may be opportunities of mutual benefit”.

To conclude, we can say that, although this move might not be the frontrunner of a large shift in the asset management industry, it does indeed show that there are opportunities to be found in this market with careful research, despite the uncertain economic outlook.

0 Comments