Introduction

Since their inception in the 1700s, Christie’s and Sotheby’s have dominated the top-tier auction market, being the closest of rivals. Characterised by staggering sales, such as Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, ($450.3m, 2017) or Andy Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn ($195m, 2022), the houses trumpeted high margins, defying market downturns post-pandemic.

Looking ahead to 2025, however, the art market outlook is bleak, marked by weak performance. Once at equal footing, Christie’s now pulls ahead, but not due to wider market forces, rather Drahi’s takeover of Sotheby’s and consequent actions. Mounting debt and controversial capital allocation have eroded Sotheby’s former standing.

Understanding why Sotheby’s trails behind Christie’s requires an analysis of the history and structure of both houses, the art and auction markets, combined with the unique operational and governance challenges Sotheby’s faces.

The London Duopoly

Sotheby’s

Founded in 1744 in London by Samuel Baker, Sotheby’s initially focused on selling collections of books. The firm successfully auctioned libraries for prominent figures of the time, such as the Dukes of Devonshire, the Dukes of York as well as the collection of books that Napoleon had taken with him in exile to St. Helena. When Baker died, the business passed to his partner George Leigh and his nephew John Sotheby, who expanded the catalogue of the house within antiquities as well as medals. When the last member of the Sotheby family died in 1861, the senior accountant of the firm, John Wilkinson, took the lead of the business and changed the name to Sotheby, Wilkinson and Hodge, a name that endured until 1924.

Over the years, the auction house consolidated its position as one of the most prominent in London. After the Second World War, Sotheby’s opened an Impressionist and Modern art department, organizing gala events during which these artworks were sold and turning these auctions into glamorous events. To expand internationally, Sotheby’s opened an office in New York and then, in 1964, acquired Parke-Bernet, the largest art auction house in the US. This move helped the firm to establish itself on a global scale and was followed by further expansion in Asia and Europe.

Sotheby’s was first listed on the stock exchange in 1977 but was subsequently taken private and listed again on the New York Stock Exchange in 1988. It was last delisted in 2019 after the acquisition by Drahi for a deal value of $3.7bn.

Christie’s

Christie’s has long been the main rival to Sotheby’s and also shared a similar development path. Established in London in 1766 by James Christie, the auction house initially focused on fine art. Similarly to Sotheby’s, Christie’s contributed to changing the perspective regarding auction houses, introducing the possibility to view the paintings and artworks before they went to auction. This helped to draw the public closer to art, at a time when public museums were not yet widespread.

Having established itself as one of the leading auction houses already across the 18th and 19th century, the firm benefitted from the expansion of the art market, managing important sales, such as the jewels collection from Madame du Barry, former mistress of King Louis XV of France.

Over the 20th century, Christie’s expanded geographically, establishing a physical presence in more than 46 countries, as well as product-wise. The auction house now offers more than 80 art categories, including watches, wines, and musical instruments. In 2024, total sales reached $5.7bn.

Performance Analysis of the Art and Auction Market

Global Art Market Conditions

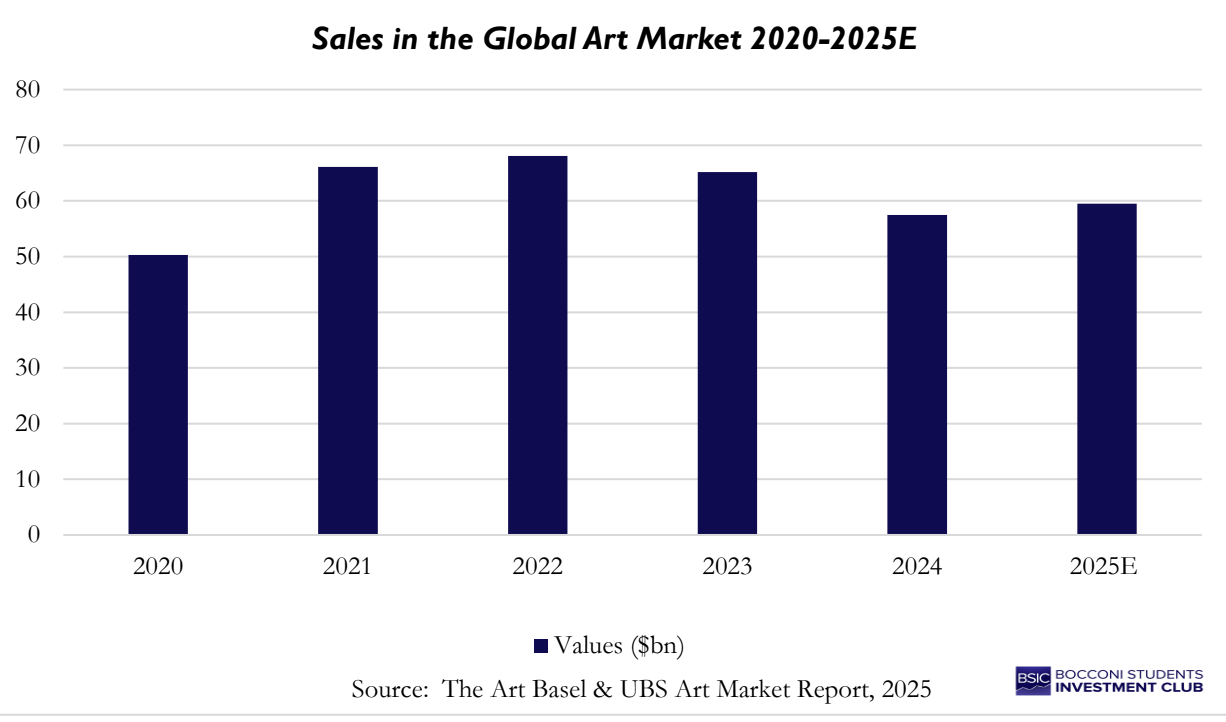

The global art market is confronting an uncomfortable reality, having hit its weakest point since the pandemic. With a steep contraction in sales in 2024 by 12% to $56.5bn, this marks a second consecutive decline for dealers and auction houses. The dismal result stems from external pressures, principally changing consumer behaviours post-pandemic, alongside broader geopolitical and macroeconomic uncertainty.

Notably, the leading driver of dragging sales is more reserved consumer spending. There has been a thinning of the high-end sales segment (those exceeding $10m) due to the backdrop of inflationary pressures, inducing a more price-conscious consumer. For instance, works under $50,000 saw an 8% increase in sales in 2024. Furthermore, as spotlighted, the overall value of sales declined; concurrently, the volume of sales grew in the same period by 3%. This indicates increased activity at lower, more accessible price-points, a shift away from trophy lots.

Geographical performance also underscores the sensitivity of art sales to the geopolitical and macroeconomic climate. 2024 sales in the US, the leading art market in terms of geography, declined by 9% to $24.8bn, due to political uncertainty of the presidential elections and the impact of tariffs. This contributed to the continued slowing at the top-end of the market, as did Chinese demand. The Chinese backdrop of slow economic growth and a persistent housing crisis weighed on seller and buyer sentiment. Consequently, the Chinese art market experienced a decline by 31% to $8.4bn in 2024, the lowest level since 2009, impacting sales.

Auction Market Conditions

The auction market mirrored the wider art market’s weakness, with combined private and public auction sales falling by 20% to $23.4bn, the lowest level since 2020. However, despite this decline, divergence emerged. Although the top-tier auction houses suffered severely from a drop in public auctions of 25% YoY, explained by reduced demand for high-end works, this was partly mitigated by private sales. These private sales have risen 14% YoY to $4.4bn, as in volatile periods, these give collectors greater control and flexibility over pricing and schedules.

Moreover, despite the overall slump in values, the volume of sales remained resilient, growing by 4% YoY, continuing the trend of improved activity at the affordable end of the market. This was driven exclusively by lower-priced lots, the most substantial segment of sales being below $50,000, reflecting again a shift to lower spending.

Considering the traditional “Big Four”, Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Phillips, and Bonham’s, collectively announced total annual revenues of $13.5bn, falling 18% since 2023. Sotheby’s reported the greatest hit (-23% YoY in sales). It suggests their dominance is eroding. Less than twenty-five years ago, Sotheby’s and Christie’s accounted for more than 70% of the world’s art auction turnover, whereas today it is just 50%, given the emergence of Chinese rivals (Poly Auction, China Guardian, and Rong Bao).

The origins of Sotheby’s issues

In order to understand the current challenges faced by Sotheby’s, we first examine its business model. Operationally, Sotheby’s can be thought of as three separate businesses. The first includes collectibles typically valued below $1m, such as wine, jewellery, furniture, or luxury designer items. These transactions, averaging around $50,000 per lot, make up the majority of the activity for the auction house. The second is the high-end art market, which brings prestige and headlines but also significant volatility, given its dependence on the tastes and liquidity of ultra-high-net-worth individuals. In particular, analyst reports showed that sales over the $1m mark, despite accounting for less than 0.5% of works sold by Sotheby’s, generate more than half of total fine art revenue. These two categories represent Sotheby’s core business as an auction house. Sotheby’s revenue from this activity depends on commissions from both sides of the transaction. The auction house charges buyers a fee of 27% on all lots, up to $1m, which adds to an additional fee negotiated with the seller. Thanks to this double-commission structure, at the height of the 1980s art boom, Sotheby’s generated $113m in annual profit. However, by 2014, when Sotheby’s was benefiting from another art market peak, profits had only risen by $29m compared to the 1980s, despite the sector’s exponential growth. The problem lies in the high fixed costs required to sustain operations. With premises in forty countries, over 1,500 employees at the time of Patrick Drahi’s takeover, and the expenses tied to marketing, shipping, insurance, and the execution of nearly 500 sales annually, the cost base had become incredibly high. Not only that, it also consists mostly of fixed costs, which exposes Sotheby’s to the risk of operating leverage during downturns of the art market.

Beyond auctions, Sotheby’s operates a sizeable financing arm. Since the late 1980s, Sotheby’s Financial Services has extended loans backed by artworks and other “passion assets” such as jewellery, watches, and classic cars. At the time of Drahi’s acquisition in 2019, SFS was originating roughly $800m in art-backed loans annually. These loans fall primarily into one of two different structures. The first, art equity loans, are simple loans in which the borrower receives upfront capital in exchange for interest payments over one to two years, typically financing 50% of the collateral’s value. The second, so-called consignor advances, are structured to give collectors immediate liquidity on works set for future sale through Sotheby’s, with repayment due once the piece is auctioned or sold privately. By the end of 2023, SFS’s loan book had grown to $1.6bn, and the platform had issued more than $10bn in credit since inception. Sotheby’s is not the only firm offering art-backed loans, with rival Christie’s also operating under a similar model. The size of this market is also quite considerable, especially given its niche nature, as Deloitte projected in 2023 that it could expand to $40bn by 2025. However, not even the financial services business of Sotheby’s has been spared by the consequences of the art market downturn. In March 2025, Sotheby’s issued “margin calls” to borrowers, as after two years of falling valuations, the value of collateral was not considered sufficient. The demand for such instruments, however, remains strong: collector not wanting to sell at lower prices, consider those loans a way to monetise their art holdings.

The first signs of difficulties for Sotheby’s emerged in the mid-2010s, when the company was still publicly traded. In 2015, activist shareholder Dan Loeb criticized the firm’s lack of innovation and governance, ultimately forcing out the CEO William Ruprecht. His replacement, Tad Smith, was tasked with modernizing the business and positioning it for growth in an increasingly digital environment. Under his leadership, Sotheby’s launched an online auction platform, investing close to $50m in it. However, the transition was not without challenges, as long-term clients began complaining of a decline in the auction house’s expertise and pricing judgment.

The ”Altice Way”

In June 2019, Sotheby’s was acquired by Patrick Drahi, a French-Israeli billionaire best known for his career in telecommunications. He is the founder and controlling shareholder of Altice, a global provider of cable, broadband, and mobile services. Drahi’s playbook in business, referred to as the “Altice Way,” was forged in Europe’s rapidly changing telecom industry of the early 2000s. Beginning with the purchase of small regional cable operators, he built scale through consolidation funded with debt. In 2005, Altice and a group of private equity backers paid €528m for Numericable, which later became the backbone of the group in Europe. Between 2002 and 2013, Drahi acquired around 20 companies, culminating in the €17bn purchase of SFR, France’s second largest mobile operator, in 2014. Expansion into the United States followed, with the acquisitions of Cablevision and Suddenlink for a combined $25bn. His strategy relied on extreme cost control and operational restructuring, which is exemplified by Drahi’s own remark “A large group counts in millions, I count in cents”. At SFR, in particular, most top executives were dismissed within weeks of the takeover, and thousands of jobs were cut once regulatory restrictions were lifted. Suppliers of Drahi’s companies usually face aggressive renegotiations, often with delayed payment terms or demands for steep price reductions. While this approach drove profitability, it was not well received by the external stakeholders. Drahi earned a reputation in France as a “cost killer,” associated with deteriorating service quality and heavy reliance on financial engineering. At the core of the model was leverage, with Drahi frequently employing complex financing structures to fund acquisitions. This included also high-profile deals; the cumulative purchase until 2023 of a 24.5% stake in the telecommunication company BT [LSE: BT.A], for example, was funded by debt and derivatives financing using the acquired shares as collateral.

The sustainability of Drahi’s “Altice Way” was questioned in recent years. In the United States, Altice’s brands, including Suddenlink and Cablevision (later rebranded as Optimum), saw their customer satisfaction rankings plummet, being rated the worst in the industry in 2022. Despite this, Drahi and his closest associates collected dividends for $1.5bn, and subsidiaries were charged management fees for the implementation of the “Altice Way”, channelled through Drahi’s Luxembourg-based holding company. By 2023, Altice had amassed $60bn in debt, exposing it to rising interest rates and growing refinancing risk. The group also faced reputational damage when a senior executive close to Drahi was arrested with corruption charges. Altice USA’s [NYSE: ATUS] shares, trading near $30 in 2021, fell below $3. In response, Drahi began liquidating assets to reduce leverage. In late 2023 and 2024, he sold a majority stake in Altice’s French data centre business to Morgan Stanley’s infrastructure fund for €764m, disposed of media assets RMC BFM for €1.55bn, and agreed to sell its online advertising group Teads for $1bn. In August 2024, Drahi’s UK holding also sold its recently accumulated 24.5% stake in BT to Bharti Enterprises for approximately $4bn.

Sotheby’s performance under Drahi’s ownership

Having explored Drahi’s ‘modus operandi’, we can find many similarities with his approach to Sotheby’s. The $2.7bn takeover in 2019 was financed with $1.1bn of new bonds and loans, while also maintaining a portion of the company’s $1bn existing debt, mirroring the high leveraged strategy pursued with Altice. Although Drahi insisted that Sotheby’s would remain independent from Altice, some links quickly became apparent. Tad Smith, the outgoing CEO, was replaced by Charles Stewart, formerly the co-president and CFO of Altice USA. Similarly to the case at Altice, suppliers faced contract renegotiations and reports soon emerged of extended payment delays to specialist service providers such as conservators. Drahi’s direct interactions with senior staff also shared similarities with the way he conducted his telecom business. He questioned headcount levels and executive compensation, arguing that Sotheby’s was structurally overstaffed and overpaid. Under Stewart’s new leadership, the auction house diversified further into adjacent businesses. The stake in RM Sotheby’s, a classic car auctioneer, was raised from 25% to 75%, while Sotheby’s expanded into luxury real estate through an investment in the company Concierge Auctions. Sotheby’s also explored ventures in hospitality and expanded its SFS lending business. At the same time, management implemented significant cost reductions, lowering expenses by roughly $100m by 2020. Compensation structures for senior specialists were also redesigned: high fixed salaries were renegotiated for incentive programs tied to long-term performance, but whose payout delays created frustration among staff.

Exogenous factors also played a role. Only months after the acquisition, the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the global art market. However, despite experiencing a decline in sales, Sotheby’s proved resilient thanks to its Viking online platform that was developed by previous CEO Tad Smith. In June 2020, the firm staged the first major online auction of the pandemic, including a $84.6m sale of Francis Bacon’s “Triptych Inspired by the Oresteia of Aeschylus”. Despite the pandemic, in fact, the financial performance in the first years of Drahi’s ownership was strong. Between 2020 and 2022, Sotheby’s reported an EBITDA of around $360m, a 40% increase to the later years of Smith’s leadership. Nevertheless, insiders reported that tensions grew within the firm as specialists, historically viewed as the intellectual core of the business, disagreed with Stewart’s management style. In 2023, Sotheby’s made a significant investment purchasing the Breuer Building on Madison Avenue in New York for $100m, which was financed through a loan from Barclays, as the new global headquarters. Meanwhile, Sotheby’s Financial Services was integrated into the group’s financing sources. In 2024, the company securitized part of its loan portfolio, bundling 89 art equity loans and consignor advances backed by more than 2,800 works valued at $1.4bn. The securitization raised $700m for Sotheby’s, with principal repayment scheduled by March 2027 and final interest payments due by December 2031.

However, by 2023, Sotheby’s financial performance began to deteriorate. The Luxembourg-based holding company of Sotheby’s reported interest expenses of $267m, up from $218m the previous year, reflecting the weight of Drahi’s leveraged strategy. By the end of 2023, in fact, its long-term debt stood at $3.5bn. Revenue also declined, driven by weaker auction services volumes. Later that year, Stewart and Drahi attempted to address the ongoing erosion of operating margins at Sotheby’s by revolutionizing the company fee structure. They introduced lower buyer’s fees and standardized seller’s commissions at 10% for most lots, alongside new fees for guaranteed works. Crucially, the new fee framework prohibited negotiations with sellers on fees. The move backfired, as rival auction house Christie’s maintained its existing fee and became overnight more attractive in terms of pricing for sellers. Sotheby’s auction profits collapsed by 88% in the first half of 2024, forcing the company to abandon the policy within seven months. In 2024, the company’s pre-tax loss more than doubled to $248m, compared with $106m in 2023. Revenues from commissions and fees fell 18%, while total art sales contracted 23% to $6bn. This was also a consequence of the art market downturn between 2023 and 2024, though it is crucial to notice that rival firm Christie’s reported an 18% increase in pre-tax profit in 2024.

The negative results for Sotheby’s, in fact, were also caused by operational setbacks, as the company shut down its Chinese e-commerce platform less than two years after committing to online expansion in the region. Then there were restructuring costs deriving from the “Altice Way” of running the company. Since 2019, Sotheby’s has parted ways with hundreds of employees, including a significant number of specialists critical to sourcing deals. Severance costs surged from $11.4m in 2023 to $29.2m in 2024, likely concentrated among senior staff as the headcount fell by only 24 units year-on-year. At the same time, Drahi extracted substantial value from the auction house. Since 2019, Sotheby’s has paid out $1.2bn in dividends to BidFair, the parent company controlled by Drahi, though they were primarily intended to service the debt load of the parent company. This was in addition to the $26.4m paid to Drahi’s personal holding company for strategic advice, introductions to banks, and guarantees of artworks; this strongly resemble arrangements common in the Altice group.

The deterioration of the company financials, in turn, meant a series of credit ratings downgrades. In February 2024, Moody’s downgraded Sotheby’s bonds to B3, one of the lowest categories of junk debt. It cited both weak operating performance and continued dividend payments, highlighting governance concerns. S&P followed in June, lowering the rating from B to B- and flagging “pressured profitability and continued EBITDA decline” alongside refinancing risk.

Things may have started to change in August of last year, as Sotheby’s secured a crucial $1bn capital injection, from Patrick Drahi himself and Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund ADQ. ADQ invested $909m for a 24% stake in Sotheby’s Holdings UK, the operating company beneath the Luxembourg parent company, as well as preferred stock and warrants. A contingent clause also allowed ADQ to acquire a further $75m of stock if adjusted EBITDA for 2024 were to exceed $300m. Drahi, through BidFair, contributed an additional $85m. The proceeds were used primarily to deleverage the firm. Sotheby’s repaid $794m of outstanding debt and allocated part of the funding toward its new Madison Avenue headquarters in New York. As a result, long-term net debt declined from $3.55bn to $2.76bn by the end of 2024. The investment of ADQ was significant also for operational reasons, as Abu Dhabi is increasingly committing to cultural investments with the opening of the Louvre Abu Dhabi and the ongoing construction of a Guggenheim museum in the city. The decision of ADQ to invest in Sotheby’s may then be seen as a way to support the establishment of a Sotheby’s presence in the emirate.

Conclusion

Overall, the art market is undergoing a structural rebalancing. While external pressures dampen growth prospects, dealers forecast 3.4% sales growth for 2025. The resilience at affordable price points and private sales provides grounds for cautious optimism, despite the current strain at the high end. Auction houses are adapting through online platforms and expansion into digital assets, but for Sotheby’s the challenge runs deeper. Strategic missteps and Drahi’s leveraged model have weakened its position, allowing Christie’s to pull ahead. In this environment, the race to remain at the top is fiercer than ever.

0 Comments