Introduction

The COVID-19 crisis has proven to be especially challenging for the real estate sector. Retail, office spaces, and any other type of real estate that functioned on the premise of people getting together in one space has been squeezed tight by the grips of government regulations as well as recommendations and best practices on how to avoid the spread of the virus. These spaces being the centre of economic activity for centuries have naturally been put in the spotlight due to their critical positioning in the crisis. However, what effect could the opposing forces of stay-at-home orders and increased unemployment paired with economic contraction have on residential real estate? This report aims to find out the varying effects of the pandemic based on geography, including how the rental market compared to the buyers’ market (including mortgages).

Rental Market

Overview

Rental residential properties are especially condensed and popular in urban areas due to a variety of factors. A lot of them ultimately boil down to higher property prices making ownership inaccessible to most, and persistent migration from rural to urban areas in the search for work. In London, the number of privately rented properties first outnumbered those occupied by owners in late 2015 and is only projected to grow towards a 60% share of the market by 2025 (already slightly above this mark in Inner London). The data also clearly points to there being a house-pricing mismatch. The percentage of rentals being occupied for less than 1 year and less than 3 years has been constantly dropping in the capital, with the less than 1 year rate standing at around 25%, portraying that rentals are increasingly becoming permanent living solutions. It can also be seen that owner-occupied properties in the city are mostly luxury or larger properties, as around 45% of them have more bedrooms than standard for the number of its inhabitants, compared to rental properties standing at less than 10% in the same metric.

Rental residences are even more common in many cities in the United States, such as New York and San Francisco, where they occupy two-thirds of the market, and in cities such as LA with 60% rental-occupation. However, one does not have to look across the Atlantic to find rental markets with even more significant shares than that of London. Both Vienna’s and Berlin’s rental housing market sits at around 75%-85% of the total market size (that is not by value, but by the number of properties that are rented), making them some of the most rental dominated markets in Europe and the world. With all this in mind, the following sections will take a look at what exactly happened to rents in different geographies, intuitively focusing on cities as they’re significantly more complete markets when it comes to rental properties.

United Kingdom

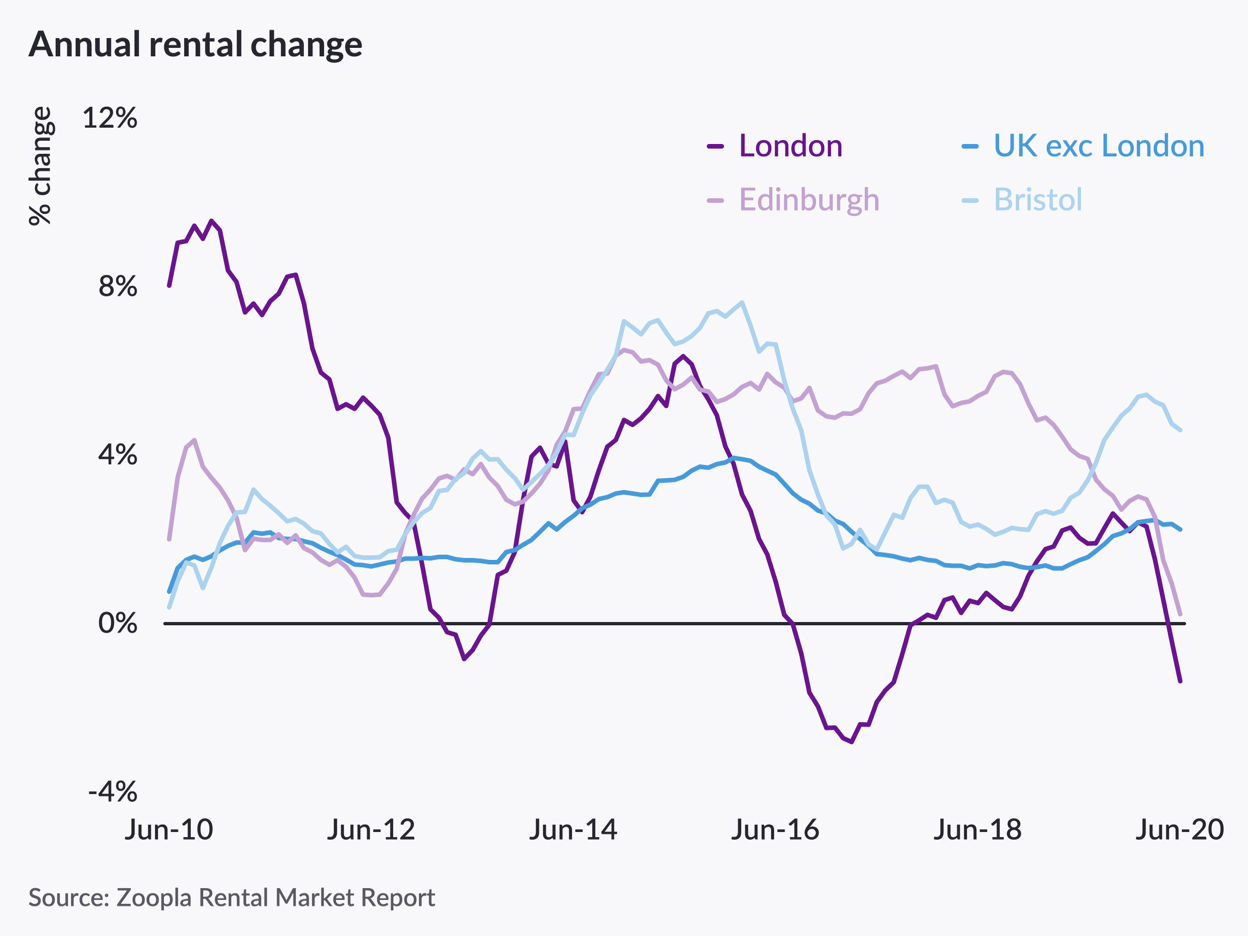

The London rental demand has been famously ravenous for many years. Rents in the city have proven to only show negative trends for short periods of time a few times ever since the 2008 financial crisis. In fact, 2020 is the first time rents experience decreases since 2017, when the 3% Stamp Duty surcharge on second homes came into effect. Zoopla’s rental index shows a fall of 2.7 per cent in the year to the end of July. This is predicted to snowball into -5% by the end of the year, according to the company’s estimates – with the decline being fuelled primarily by inner London. This is due to the properties in the area being heavily dependent on tenants willing to pay a premium for a location closer to work, as well as longer-stay rentals from foreigners.

Source: FT

The rest of the UK is experiencing more of a flattening of rents rather than a decline, but some cities such as Edinburgh are pressured by rules aiming to curb the proliferation of short-stay properties for tourists. Seemingly, tourism should not affect the rents charged in the general market for long lets. However, as tourism has been practically brought to the ground, especially during the first and the current second wave of coronavirus, landlords of Airbnb-style properties have switched to offering longer residential leases, increasing the supply in the market.

This problem is paralleled by another one in London, where around 450 short-let operators take leases on residential properties and repackage them as corporate lets for business travellers, whose number has barely made a similar temporary recovery during summer as the one seen from tourism. Once again, all these businesses have to limit their losses, and therefore flood the market for traditional residential rentals. London also being a popular career-start spot for graduates is suffering from companies’ muted intake this year due to the challenging business headwinds, and a part of that intake being stolen by fully online internships.

The seasonal influx of international students at higher education institutions is also down from its usual levels. However, the “rental problem” goes beyond the forces of decreased demand. The “eviction ban” that was put in place to protect many that lost their jobs due to the pandemic, and has been in place throughout summer, is no longer in existence. While its reintroduction is still a topic of government debate, many court cases have already begun surrounding the eviction of tenants that failed to pay rent. While the share of residential tenants that failed to pay their rents has significantly decreased since the start of the pandemic, it’s still a fragile number that could once again be spiked by the second wave. As showcased by March and April, when more than 50% of landlords reported not getting their full share of rent payments. It must also be remembered that this is a dangerous problem as around 44% of landlords use rent to contribute to their pension and 39% receive a gross non-rental income of less than £20,000 a year.

While so far, the focus of London’s and UK’s policymakers has been halting rent rises in the capital. London mayor, Sadiq Khan, has asked to be given the authority to freeze rents in the capital for two years, as some recent data from before lockdown still pointed to around 10% of tenants being behind on their rent payments (this is only proven to get worse with lockdowns, as seen during the first wave). However, a debate around freezing rents seems to be a misguidance of resources, as the capital’s forces of supply and demand have already proven to work in favour of tenants. Furthermore, surveys regarding the views of tenants have found the majority of landlords to be sympathetic over rent shortfalls during the pandemic. Landlords are also not quick to go to court for the eviction of their tenants who have only slightly fallen behind on rent or only demand an extended deadline of payments; with uncertain times ahead, only the most optimistic landlords trust that there’s a prospective renter in the market to fill the vacancy an eviction would create. Hence, as long as the current trends uphold, the forces of the free market have been quite good to tenants in the capital, while not making it especially challenging for those in other cities.

Readers also interested in the comparison of how other cities in the UK have fared in the challenging economic environment posed by the pandemic are invited to study the graphs below:

Source: Zoopla Rental Market Report

Source: Zoopla Rental Market Report

United States

On the other side of the pond, the situation with residential rental prices seems to be even more dynamic. Nationwide, November rents have fallen by 1.4% over the past year, with a steep decline of 17% in New York. Many other cities also saw decreases, including San Francisco (-23.4%), Boston (-15.9%), and Seattle (-12.2%), according to the Apartment List. Other drastic data from Realtor.com shows that median rent prices for studio apartments in San Francisco declined 31% year-over-year to $2,285 in September. All this is showing that declining rent prices is an urban-centred topic in the United States.

In terms of rent repayments, the situation is not critical, with most tenants making their payments at a similar rate to 2019. It is key to take note of a large part unemployment benefits and stimulus play in these statistics, as rent payment rates for August only dropped by 7.7 percentage points in Las Vegas and 7.5 percentage points in LA, compared to the same time last year, with a similar trend visible across the country. However, New York has told a different story, with only 64.5% households making their rent payments in the same period, showing around a 20-percentage point drop to the year before.

The situation for New York proves to be one of the most critical in the country ever since the first wave of the virus. In the 3-month period from April to June, it is estimated that a quarter of the 5.4 million renting New Yorkers have not made a single rent payment. In the same period, this left an even higher share of landlords, standing at 39%, not making their payments of property taxes.

To curb these negative effects of the pandemic, an additional COVID-19 Rent Relief Program was passed with federal funds to be distributed in November of which $100M went to New York. However, this has proven to not be a quick source of relief as out of the 94,000 applicants who sought the state’s help covering unpaid rent only around 15,000 applicants received a collective $40 million in rent relief that will be paid to landlords across New York, leaving roughly $60 million in allocated federal funds on the table.

The situation may be appearing to take a positive turn in October, with lower rents in New York luring younger tenants to get back into the city. New leases increased 33% in October, making it the best October in 12 years, according to a report from Douglas Elliman and Miller Samuel. However, with the second wave and further lockdowns already glooming upon the US, this may be just false hope, and ultimately lead to even more tenants unable to pay their rents in the coming months.

With the next stimulus being delayed over disagreements between the Republican and Democratic Parties, the situation for all US households is getting increasingly dire and the outlook grimmer. Already, 32% of US households are facing the prospect of being evicted or having their homes foreclosed on.

Other Markets

It has now been more than a year since, in a bid to fight skyrocketing rents (44% over the past 5 years), the city of Berlin not only froze rents for 1.5m homes (the Mietendeckel policy), but also gave tenants the right to demand repayment from November 2020 if they were charged more than city-imposed rates. This means, in line with the policy, around 340,000 tenants are getting their rents lowered this month to match the city-wide rental index. So, while the forces of supply and demand on rent prices wouldn’t be accurate if analysed in this scenario, the Berlin residential rentals market has been impacted by the pandemic in a unique way. Landlord lobby groups say many of their members are suspending any investment in their apartments. As the economic uncertainty continues to grow, landlords are taking drastic action: renting only to friends and family, or even selling off their rental apartments to owner-occupants. Germany’s leading property website further confirms this with data, pointing to a 40% decrease in the number of rental apartments available in Berlin in the past 2 months.

Other interesting markets include Seoul, South Korea, where despite the negative effects of the pandemic, rent prices continue to go up due to an extreme housing shortage. Just this week, the government stated that it would provide 114,000 homes for public housing over the next two years by buying empty hotels and offices and renovating them as residential studios.

Ownership Market

Overview

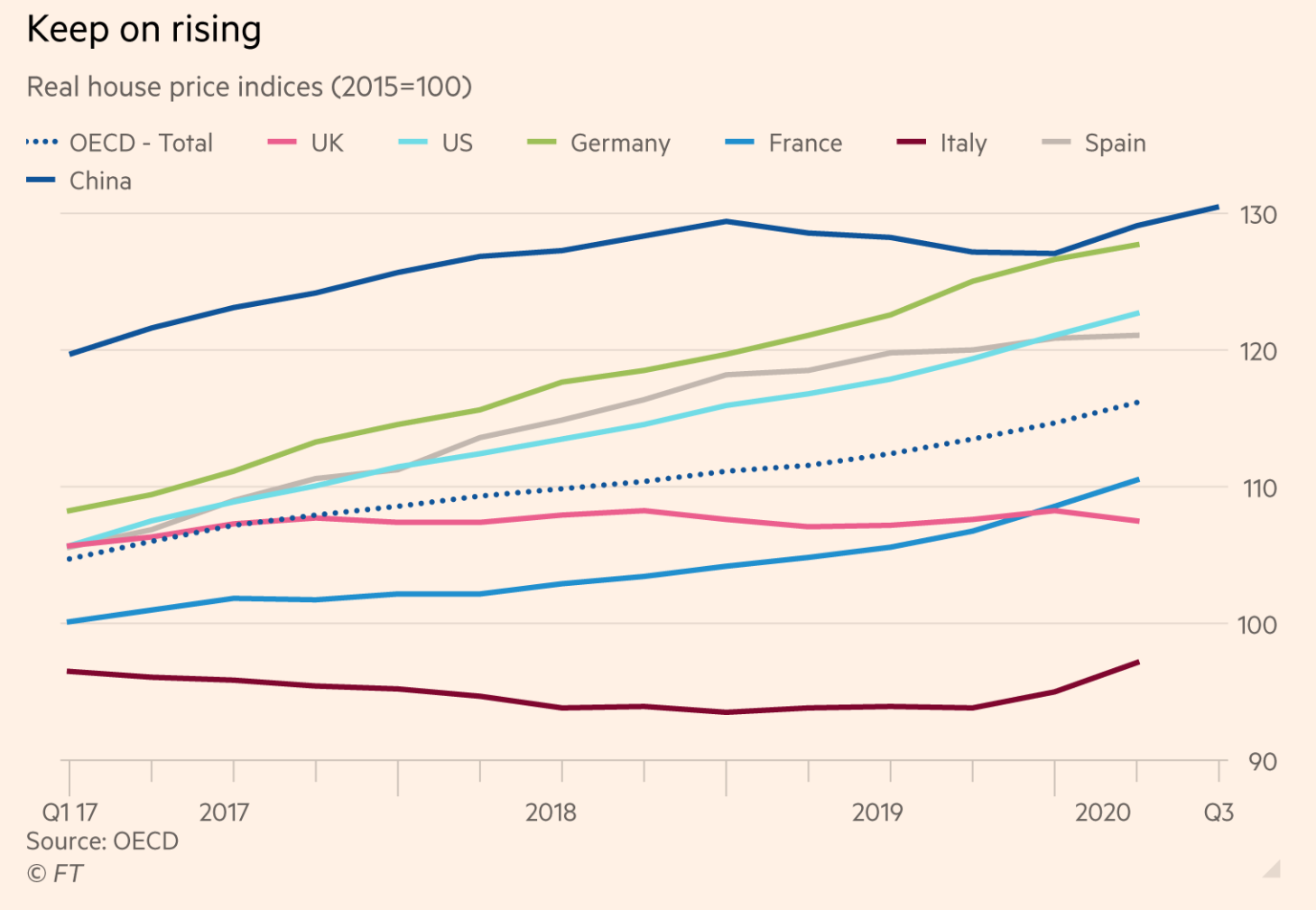

Usually, prices in the housing market tend to fall during an economic downturn. But this year, with a deep global recession caused by the coronavirus pandemic, property valuations have kept on rising in many countries. House price growth has accelerated to an annual pace of almost 4% among the OECD countries, with even faster rises in Europe and the US.

The economic recovery is still not happening, wealth is down, and rents are falling in most cities, so your alternative to buying a house is getting cheaper. So, can the fundamentals be connected to an ongoing housing boom?

Helping the resilience of housing markets are the vast stimulus packages from governments and central banks that have supported companies, allowed many workers to keep their salaries, and kept borrowing costs near record lows. In the US, falling mortgage rates and higher state benefits combined caused the rise of the housing market in the pandemic. There were even sharper price rises in Europe, notably Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal and Poland. Prices in Russia have soared 15 per cent, fuelled by state subsidies. As housing costs keep climbing and working from home is becoming frequent, the pandemic is prompting some people to abandon expensive city locations in search of more space.

Source: FT

United Kingdom

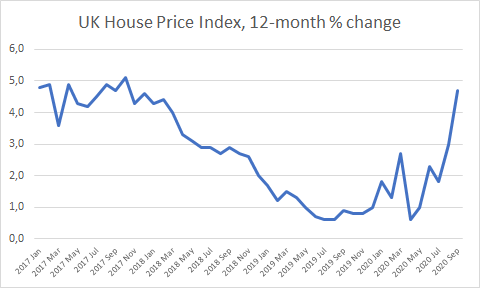

The UK property market has experienced a “mini boom” since restrictions were eased in May. In October, the average property price was up 7.5% from the previous year, hitting a new record high. The strength of the housing market, despite a glooming economic situation, was partially the result of demand accumulated during the lockdown when the housing market was on freeze. Moreover, some analysts have warned that the government’s stamp duty holiday, which began in July and will run until the end of March, is creating a mini-housing bubble.

How does the stamp duty holiday work? Homebuyers pay no tax on the first £500,000 of any transaction in England and Northern Ireland until the end of March, in an attempt to boost the property market, hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic. The stamp duty holiday is part of a package of wider stimulus measures announced by Rishi Sunak, the Chancellor of Exchequer, in July. The measure means that 90% of people buying a main home would pay no stamp duty at all, while the average tax bill would fall by £4,500. Anyone buying a property above the temporary threshold can save £15,000.

Consequently, the feeling and concern is that buyers are feeding into an artificially strong market, which has been driven by historically low mortgage rates and a rush to complete transactions before the end of the stamp duty holiday in March.

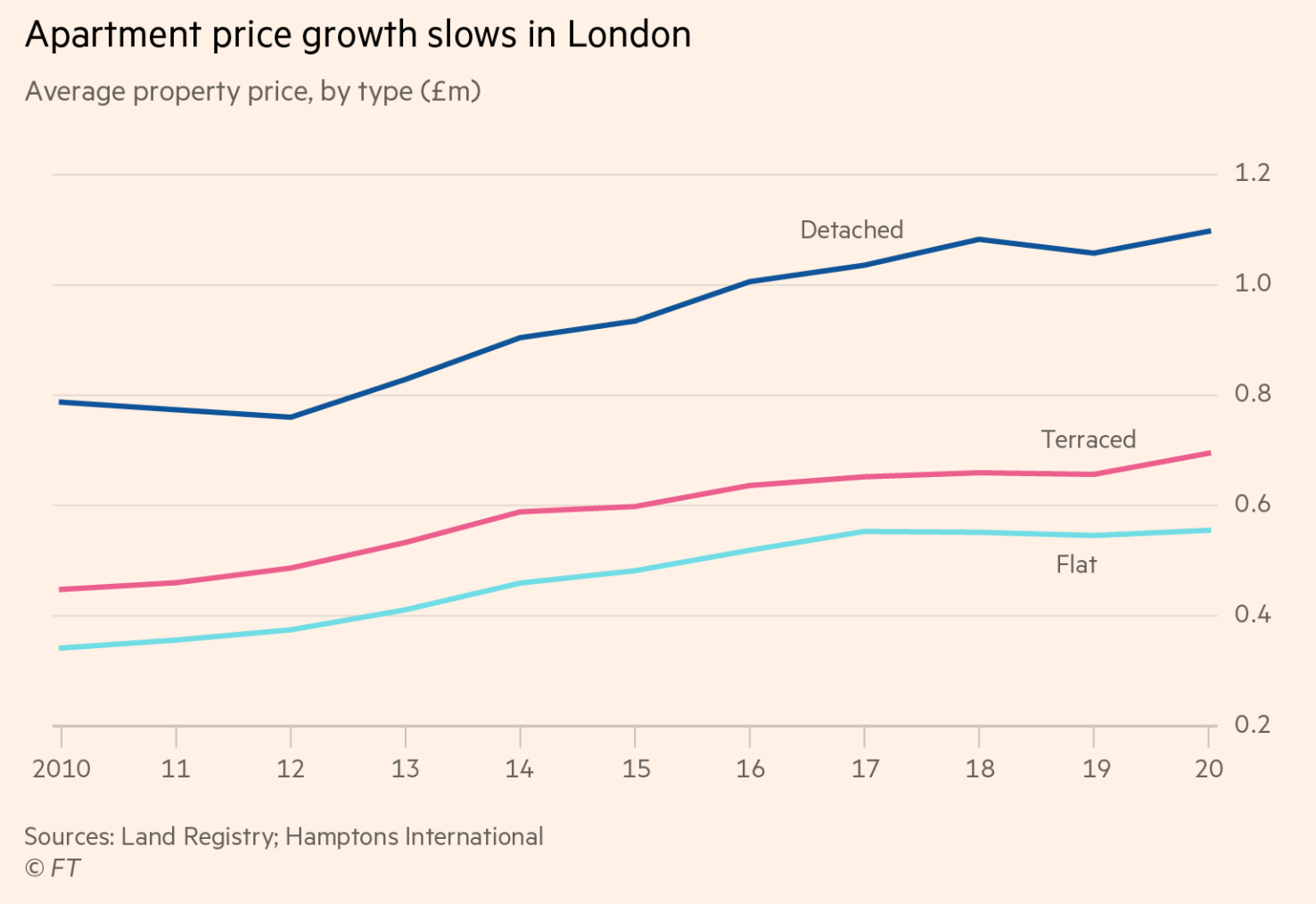

The pandemic may also have prompted buyers to change preferences by looking to move to larger properties with gardens. Data showed that the average price of detached houses rose 6.2%, while flats and maisonettes increased 2%.

As banks struggle to cope with the booming demand in mortgages, they are turning away from it by increasing interest rates on many new home loans. Lenders are putting up rates to deter potential borrowers, also because coronavirus restrictions left a lot of bank staff working from home, limiting their capacity to process applications. High mortgage rates partly reflect lenders taking advantage of the surge in demand, but they also reflect a re-pricing in response to the deteriorating labour market. Banks had already suspended many deals on low-deposit home loans, hitting first-time buyers who typically put down 5-10% of the house price as a deposit.

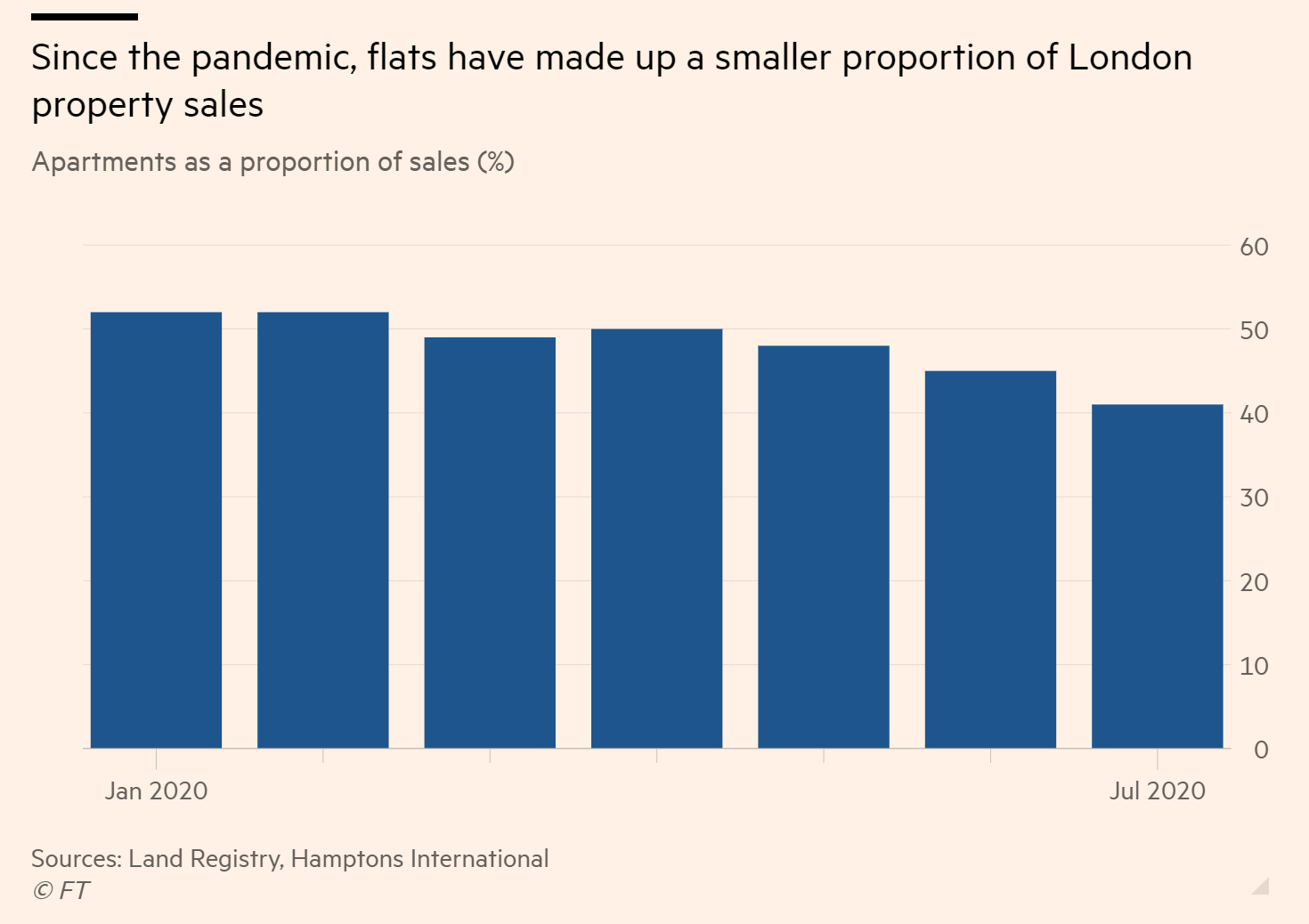

London isn’t experiencing the same “mini-boom” of the whole UK property market, because the pandemic is causing an increasing number of buyers to abandon the idea of buying a flat. In London, the average price of a flat went up by more than any other property type between 2011 and 2019. However, since the beginning of the year flats have been the weakest performers. This year is the first time in more than a decade when flats make up fewer than half of all property sales. It adds that London flats are taking 70 days to sell on average, whereas houses are taking just 29 days. Moreover, just 27% of all flats listed for sale are finding buyers, compared with 44% of houses.

Part of this is because of a drop in first-time buyers, who frequently purchase flats, another reason, already described, is that in the wake of Covid-19 and work from home, having a property with enough space, particularly for a home office, is crucial for buyers. Moreover, the proportion of UK properties bought as first homes has fallen to its lowest level in five years due to the economic fallout of coronavirus, and the reduced availability of higher loan-to-value mortgages, commonly utilized by first buyers.

Indeed, this year houses have made a higher proportion of property sales in London’s luxury areas than ever in the past decade. Values of flats sold in these areas are 1.8 % lower than a year ago, whereas house prices rose 6.1%. As said before, the picture has echoed nationally, with houses selling faster than flats for the past six.

Another reason for the sharp decline in the popularity of expensive flats is the fact Covid-19 is keeping away foreign buyers, who traditionally bought vast parts of the capital’s apartment stock as way to park their money offshore.

Source: FT

Source: FT

United States

In the US, after home sales almost halted during the depths of the first wave of the virus, activity rebounded sharply. October sales marked a 26.6% increase from a year earlier, confirming a rise for the fifth straight month. Home prices rose in every corner of the US during the third quarter, as the pandemic boosted activity. The median price for existing homes rose in the third quarter from a year earlier in each of the 181 metro areas tracked by the National Association of Realtors (NAR). Americans are viewing their home as something more than what it was before, as they spend more time in them due to the pandemic, they are more interested in larger-size homes, and naturally those more expensive ones.

Real-estate agents and economists credit the strong demand for housing to record-low interest rates, a large population of millennials entering prime homebuying years and a desire for more household space driven by the coronavirus pandemic. As many people work and attend school from home, buyers prefer to move further from their offices in exchange for bigger houses with more outdoor space.

Moreover, a very limited supply of homes for sale, especially in lower price tiers, pushed prices to new highs. October was the fifth straight monthly with a price increase in one of the best stretches for the housing market in several years. The median existing-home price rose 15.5% from a year earlier to $313,000, a record high in both nominal and adjusted for inflation terms.

Existing-home sales also rose 4.3% month-on-month in October from September, to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 6.85 million, the highest level since February 2006. While there were just 1.42 million homes for sale at the end of October, down 2.7% from September and down 19.8% from October 2019. Which means, that at the current sales pace, there was only a 2.5-month supply of homes on the market at the end of October, a record low.

Buyers have been aided by mortgage rates now at their lowest level since Freddie Mac began tracking them in 1971. The 30-year fixed-rate mortgage averaged 2.72% for the week ending November 20, nearly a full percentage point below where rates were a year ago, Freddie Mac reported. During this same time in 2019, these loans had an average rate of 3.66%. But mortgage rates are unlikely to fall further from here, as positive news about a coronavirus vaccine is making investors more confident.

For these reasons the S&P Homebuilders Select Industry index is up 24.2% this year, compared with a 10.8% rise for the S&P 500 (data on November 19).

This implies that it is an excellent time to be a mortgage lender. The volume of mortgage refinancing applications, while down from the spring, are still about 60 per cent higher than they were a year ago, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association. Purchase mortgage applications are about 20% higher.

Profitability for the US mortgage lenders is strong, too. The difference between the average rate consumers pay on their mortgages and the coupon on a government-backed mortgage bond – a rough proxy for lenders’ profit margins, because it tracks the difference between what lenders can buy mortgages for and the price at which they can sell them in the bond market – stands at 1.6%, against pre-Covid levels of around 1%.

As home prices continue to rise, affordability is a growing concern. Record-low interest rates have offset much of the effect of higher prices for consumers, but the shortage of homes for sale is leading to bidding wars, making it harder for first-time home buyers to enter the market.

Germany

Soaring property prices are also causing concern in Germany, where the central bank said in a report that apartments in the country’s biggest cities were 30 % overvalued compared to the long-term ratio of prices to rents. The central bank also stated that this movement reflects rising land prices rather than speculative demand motives. The volume of land sold each year in larger cities has fallen by a third since 2012 while prices have more than doubled. The number of new apartments built in the country last year rose 2% but remains well below the demand. With Germans having 10-year mortgages at rates as low as 0.6% and some banks offering to lend the full purchase price, it is easy to understand what is fueling the market.

0 Comments