The modern economy is increasingly driven by intangible assets, such as intellectual property, brands, and networks. However, common measures of value have failed to adapt to this transformation. The path forward involves both accounting reform and improved methods to directly value intangible assets.

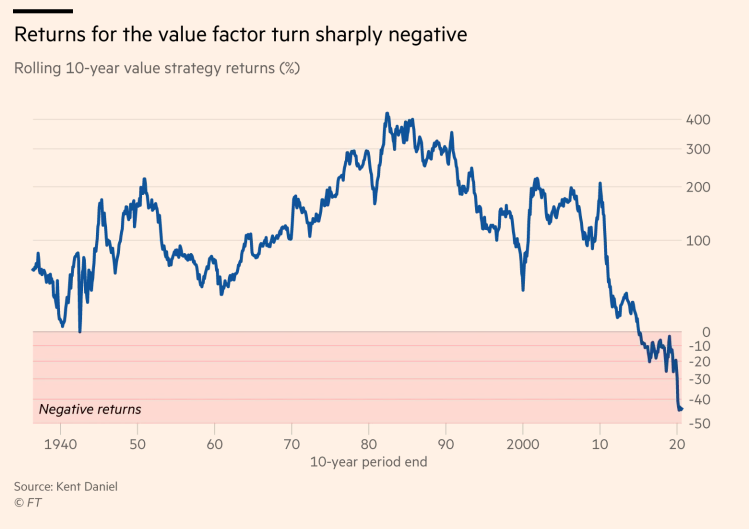

Value strategies have worked well across multiple asset classes, periods, and geographies. However, for stocks, the last decade has been tough, with value strategies facing significant headwinds, especially in the last few years. In the financial press, there is a continuing debate about the poor returns of stocks with low multiples of Price-to-Earnings (P/E) or Price-to-Book (P/B), and many ask themselves if value investing is dead.

Recently, value investing meant buying stocks with low valuation multiples and selling those with high multiples. However, this should not be confused with value investing.

Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing and Warren Buffett’s mentor, in his most famous book “The Intelligent Investor”, explained why prices diverge from values and discussed the margin of safety, which impressed the importance of finding large gaps between price and value. Differently, from the evergreen Graham’s definition, the poor performance for value strategies over the past decade is based on the original HML (high minus low) factor popularized by Fama and French (1993). The well-known paper showed that adding measures of size and value to the CAPM beta righted the relationship between risk and reward. The value factor, measured as a multiple of Price-to-Book per share, revealed that stocks with low multiples did better than those with high ones. Value investing suddenly became synonymous with buying stocks with low multiples and avoiding or shorting those with high multiples.

Source: FT

This introduction was dutiful because now some investors still conflate value investing with the value factor. Value investing is buying something for less than it is worth, while the value factor is a metric based on Fama and French that can be variously adjusted. So right now, we can start our discussion on the impact of the rise of intangibles on the value factor.

Earnings and Book Value no longer mean what they used to. It is not surprising that a strategy that’s “worked” through the 1920s – when a lot of stocks were railroads, steel, and steamship companies – through the Great Depression, WWII, the 1950s – which included some small technological changes like rural electrification, the space race, and all the technology that it spanned – now faces challenges.

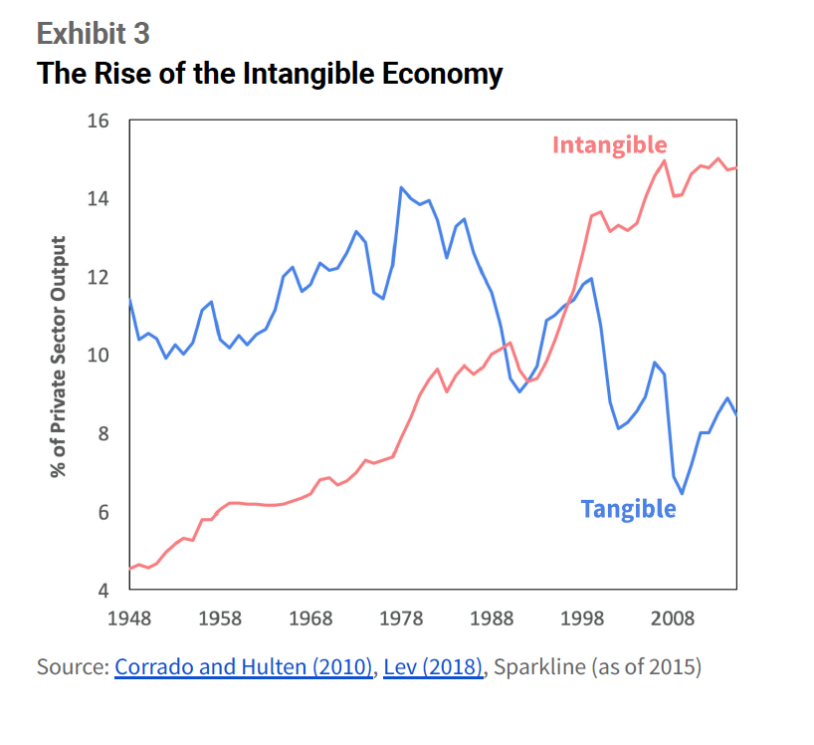

In that time tangible assets, such as factories, were the foundation of firms’ value. Differently now, intangible spending, such as R&D, has been on the rise. The issue with intangibles investments is that they are treated as an expense on the income statement, while tangible investments are recorded as assets on the balance sheet. So, a company that invests in intangible assets will have lower earnings and book value than one that invests an equivalent amount of intangible assets, even if their cash flows are identical.

The questions arise: are the accounting measures we use to measure value not capturing the fact that we are now living in an era when a handful of “global winners” can capture excess monopoly rents? Or maybe the strategy is not working because there are too many people now aware of it to work going forward? Might overreliances on the Price-to-Book factor be the issue? May flows into index funds have driven the biggest, most expensive names up wildly?

The conservative nature of the accounting system crashes with the equity valuation need of financial statements that are sufficiently precise. Unluckily, the financial reporting system is based on a vast set of, ultimately subjective, accounting standards and accounting practices that have evolved, to record an ever increasingly complex set of transactions. The output of this reporting system is the set of primary financial statements (income statement, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows) that is at the heart of any value investor’s toolkit. There are some (e.g., Lev, 2017) who argue strongly that financial reporting information is no longer relevant, in part due to accounting standard setters walking away from the traditional matching implicit in income recognition, and in part due to the accounting system failing to recognize increasingly important intangible assets.

While we can all argue that the accounting system may miss capitalizing on certain aspects of the value-creating activity, such as research and development (R&D) as well as advertising, we also know what the rules are that govern the accounting system. We are all free to make adjustments to ‘un-do’ any perceived imperfection in the accounting system and these will be outlined in the last part of the article.

Impact of intangibles on valuation metrics

In this paragraph, we will address the problem that value factor investing may become less efficient when the stock of intangible investment by companies is relevant.

As stated before, quantitative value investment strategies try to exploit the existence of undervalued and overvalued companies work by identifying such companies using financial ratios, for instance, Price-to-Book (P/B) or Price-to-Earnings (P/E), which are highly affected by accounting methodologies for intangibles. The main ways intangibles have an effect both on a company’s balance sheet and income statement and the valuation metrics derived from them are the following:

1.Low transparency for intangible accounting items

While most firms itemize R&D costs, brand, and culture related expenses are usually recorded under the general catch-all line item of “selling, general and administrative expenses (SG&A).

Valuation distortion and intricacies: low transparency of accounting items makes it extremely difficult to evaluate intangibles

2. Intangibles might not be recorded on the balance sheet (brand, network effects…)

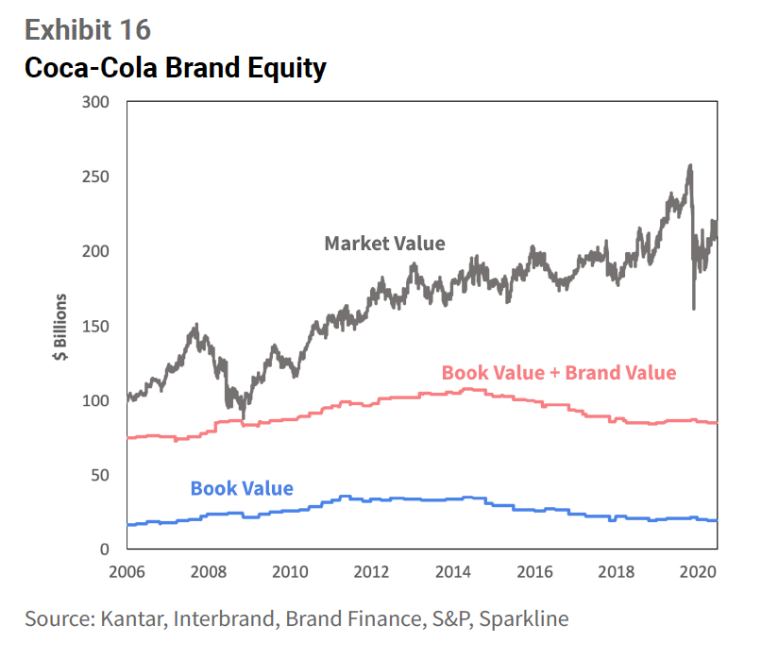

Brand equity refers to a value premium that a company generates from a product with a recognizable name when compared to a generic equivalent. Companies can create brand equity for their products by making them memorable, easily recognizable, and superior in quality and reliability. Brand equity value, when generated internally, is not currently recorded on the balance sheet or in any financial statements. The lost capitalization of this intangible asset can lead to extremely high P/B ratios, suggesting that the company is overvalued whilst other ratios tell a different story. The Coca Cola company is probably the greatest example of this discrepancy.

In 2019, Coca-Cola spent $4.25 billion on advertising. Over the past 25 years, it has invested a cumulative $67 billion in building its brand. This massive investment has built its key competitive asset. The value of the Coke brand is illustrated by the famous Pepsi Challenge marketing campaign. Pepsi showed that in a blind taste test subjects preferred Pepsi over Coke. However, subsequent studies found that, when the bottles were labeled, subjects preferred Coke. This was termed the “Pepsi Paradox.” Future studies conducted in labs even linked Coke’s positive brand associations to specific brain activity.

The value of Coca Cola brand equity, measured by several marketing firms, is around $60 billion. The market capitalization is $223 billion and the book value is $19 billion. This makes up for a ridiculous 11.7x P/B ratio. However, other ratios such as EV/EBITDA and P/E depict a more conservative situation for the company from a valuation standpoint. This is because of revenues and earnings from the brand flowing through the income statement. When brand equity is taken into consideration, the P/B ratio decreases to a much more reasonable 2.7x.

Network effects represent another intangible asset that is not currently recorded in any financial statements. The power of network effects derives from the ability to generate increasing returns. Network effects are a phenomenon whereby additional users enhance the value of a product to its existing users. This creates a positive feedback loop. Once a network has a critical mass of users, it becomes extremely challenging for competitors, even those with technical and brand superiority, to lure users away. Thus, a mature network is itself an asset.

Here’s Warren Buffett explaining why he invested $35 billion in Apple from 2016 to 2018 when the company was trading at over four times its replacement cost (Book Value):

“I didn’t go into Apple because it was a tech stock… [but] because of the value of their ecosystem and how permanent that ecosystem could be.”

We could make a long list of companies, who are dubbed to be extremely expensive in relation to valuation metrics, whose investment thesis is entirely, or at least hugely, built on their potential to become the sole platform in their business area. Examples of companies belonging to this bucket are Uber, Airbnb, Box, Square, PayPal, Shopify…

Valuation distortion and intricacies: higher P/B ratios for companies with valuable brands and difficulty to estimate growth rates and future pricing power of platform companies which could potentially become a monopoly

3. Organic growth versus external growth

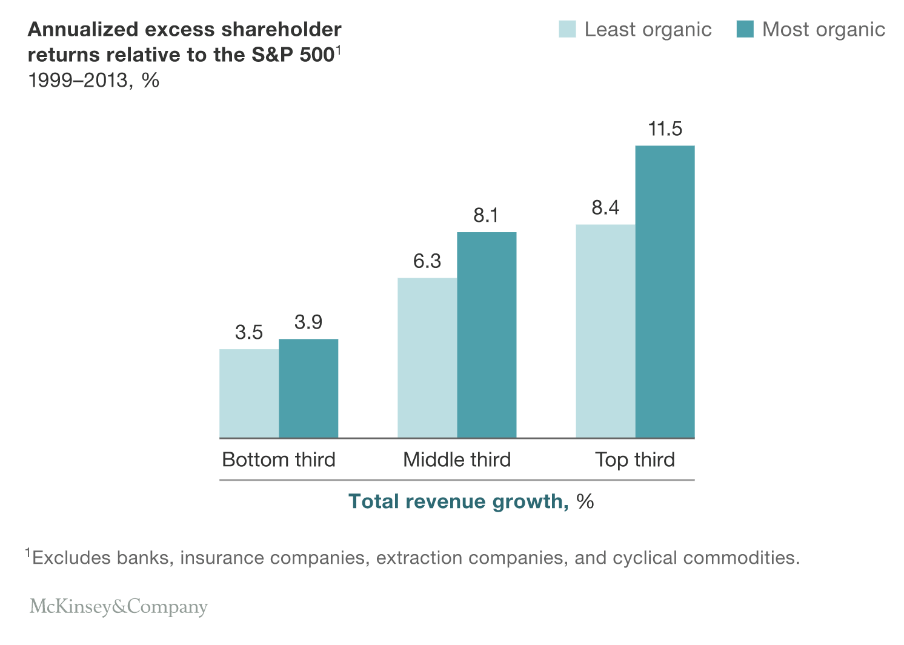

Companies that engage in serial M&A activity have a stronger balance sheet than firms that focus on organic growth. Indeed, intangible assets acquired via M&A are capitalized (e.g. goodwill) while internally-generated intangibles are not capitalized. Therefore, we could have a situation where two companies, Company A (the serial acquirer) and Company B (history of organic growth), belonging to the same sector and of the same size, generate identical cash flows but Company B is considered overvalued because the denominator in the P/B ratio is lower.

Value Factor screening based on limited accounting ratios may fail to recognize that the two companies are identical.

If a company decides to follow the path of organic growth, it would probably take longer to boost earnings than acquisitions do and balance sheet accounting would set a lower value for Tangible Book Equity. Therefore, Value Factor might miss on these companies as they have higher levels of P/B and P/E. However, a 2017 research from McKinsey recognizes the existence of a value premium in organic growth. Indeed, in growing through acquisition, companies typically have to pay for the stand-alone value of an acquired business plus a takeover premium. This results in a lower return on invested capital compared with growing organically.

Source: McKinsey and Company

Valuation distortion and intricacies: higher P/B and P/E ratios for companies with a history of organic growth rather than external expansion

4. The problem with capitalizing intangibles

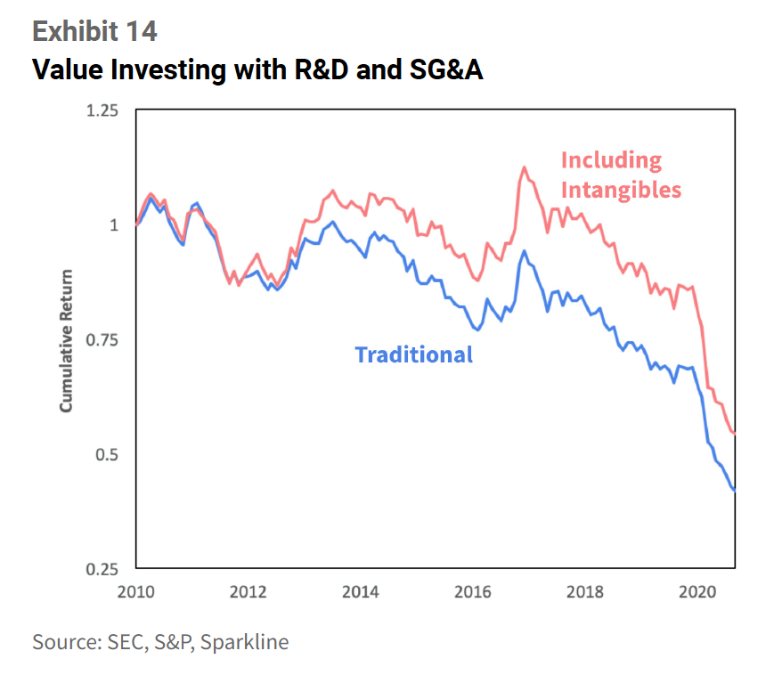

Kai Wu’s research paper “Investing in the Intangible Economy” shows how the value factor performance in the last decade experiences a sharp drawdown even when R&D and SG&A expenses are capitalized.

The capitalization of intangibles is based on the fundamental assumption that intangible assets should be treated like tangible assets. While this is better than pretending intangible assets don’t exist, it disregards the properties that make them so special. The main characteristics of intangible assets are uncertainty, due to the highly stochastic nature of intangible investments, and scalability, since the marginal cost is close to zero (once the code is written, producing an additional unit costs nothing).

Valuation distortion and intricacies: intangible assets are speculative in their nature and to calculate their fair value is a really complex, if not impossible sometimes, exercise

5. The role of R&D expenses

Investments in R&D have highly variable outcomes. A €10 million research project could be worth nothing, in this case it is recorded as a sunk cost, or billions. For this reason, accountants even value R&D using a “real option” approach (Yes, you could end up using the Black & Scholes formula to estimate the profit from successful commercial exploitation of a research project).

In the biotech industry, we see that companies invest on average 27% of revenue in R&D. The distortion of Price-to-Earnings measures could be an argument, as for biotech companies R&D expenses are deducted from their bottom line. Let’s take a look at the last decade’s performance of iShares Nasdaq Biotechnology ETF, which has an average P/E ratio of 19.8x.

Valuation distortion and intricacies: distorted P/E measures for R&D intensive industries and highly stochastic nature of research projects

Possible adjustments to value strategies

As stated before, a strong limitation of all valuation approaches is the quality of the data inputs and for the equity valuation, this means that the quality of the financial statements needs to be sufficiently precise. We can all argue that the accounting system may miss capitalizing certain aspects of the value-creating activity, such as research and development (R&D) as well as advertising, but we also know what the rules are that govern the accounting system. In this paragraph, we will discuss some of the possible adjustments that can be put in place to also consider the impact of the intangibles on the companies’ balance sheets and income statements.

First, you need to expand your horizons when it comes to measuring value. Book Value is not the only fundamental anchor for price. Book Value should form a part of any systematic valuation strategy but focusing on just one fundamental anchor for intrinsic value is unlikely to be a successful strategy. Moreover, a classic criticism of P/B type metrics is that Book Value is stale (e.g., Kok, Ribando, and Sloan, 2017), so a firm may appear to be cheap (as indicated by a low P/B ratio) but that is simply because B has not yet been written down, and the stock price already reflects that write-down. Indeed, Kok, Ribando, and Sloan (2017) suggest that book values tend to mean revert to prices instead of prices mean reverting to book values.

Instead, we should ensure that a multitude of fundamental measures is utilized to compare against price. Both historical and near-term forecasts of balance sheet items (for example book equity) and income statement or cash flow statement items (for instance: sales, earnings, or cash flows) will help improve measures of value. Any limitation in Book Equity (e.g., missing intangibles, or stale assets that have not been written down) can be moderated via using multiple measures of value and by industry-adjusting the respective value measure. Moreover, adjustments may be made to accounting attributes used as anchors in value measures, or those adjustments can be incorporated directly into the broader investment process.

To overcome the possibility of an accounting standard systematically missing an asset (e.g., research and development) we can compare similar firms within an industry that is R&D intensive, as opposed compare an R&D intensive firm with a retail firm (see Asness, Porter, and Stevens, 2000). An alternative approach may be to construct firm-specific capitalization schedules to bring onto the balance sheet any excluded economic asset. More recently, Lev and Srivastava (2020) suggest that capitalizing R&D expenditures and Selling, General & Administrative expenses, and amortizing this ‘asset’ over industry-specific schedules yield adjusted, will improve measures of Book Equity and earnings. Their empirical analysis suggests an improvement in value strategies.

Another adjustment is to exploit the data vendors attempting to correct the multiple limitations embedded in the financial reporting system, mainly Credit Suisse HOLT and New Constructs. These changes are far from simple though as significant choices are needed to reconstruct financial statements.

HOLT (Credit Suisse) and New Constructs typically re-compute earnings and cash flow metrics by adjusting reported financial statements to undo some of the conservative choices embedded in the financial reporting system, for instance: capitalize research and development expenditures and adverting expenditures instead of immediately expensing them. These adjusted earnings and cash flow numbers could then be used as alternative fundamental anchors to price, or these adjusted earnings numbers could be compared to reported earnings numbers and the difference could become another attribute to seek exposure to in a portfolio.

To verify the criticism that accounting fundamental based measures of value have become less useful, we can assess the performance of valuation metrics using adjusted operating cash flows. As an example, AQR used in its recent paper “Is (systematic) Value Investing Dead?” data from Credit Suisse HOLT. HOLT constructs an inflation-adjusted gross cash flow which is computed as net income adjusted for special items, depreciation & amortization, interest expense, rental expense, minority interest, and various other proprietary economic adjustments (CFHOLT). We can convert this to a valuation multiple scaling it by enterprise value as estimated by HOLT (EVHOLT). The ratio CFHOLT / EVHOLT, is then directly comparable to the CF/EV multiple. Even though the Credit Suisse HOLT improves the financial statements for valuation purposes, the key inference that AQR drew in its recent paper is that it appears unlikely that the growing importance of intangibles or changes in business models is explaining fully the underperformance of value strategies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the underperformance of the value factor can be assessed for a variety of reasons, ranging from increased share repurchase activity, the changing nature of monetary policy and the potential impact of lower interest rates, the value measures that are too simple to work, and the rise of ‘intangibles’ and the impact of conservative accounting systems. In this article, we focused on the impact of intangibles on the value strategies but for completion, across each criticism just stated there is little empirical evidence to support them.

The rise of the intangible economy has changed the rules of investing. Intangible assets comprise almost half of the capital stock and their importance grows steadily each year. Their omission from financial statements distorts our perception of value. However, intangible assets are uniquely uncertain and scalable. Thus, even accounting reform is unlikely to lead to a clear picture of the intangible economy. We need to go beyond accounting data to measure intangibles such as: brand equity, patents, and network effects more directly. Despite there is not much evidence that shows that the underperformance of the value factor is due to these intangible assets, they remain a factor and they are often disvalued. So, in our opinion, the quoted adjustments remain useful for every strategy in particular for the value ones.

0 Comments