Introduction

Everyone who took a macroeconomics class knows that the control of interest rates is a fundamental tool in economic policy. Monetary expansion or contraction has a real impact on inflation, GDP growth, and exchange rates and thus, central banks have tight control over the base rate in the economy. Theoretically, low-interest rates fuel economic expansion by incentivizing investment and borrowing. Since the 2008 financial crisis, central banks worldwide started buying up assets to artificially lower the risk-free rate and to sustain the weakened economies. During the past decade interest rates have stayed low and even went negative in some countries. This is a symptom of economies that even before the COVID-19 pandemic needed monetary stimulus to function. Low interest rates then spilled over to healthy economies as well due to capital mobility and monetary unions. After the pandemic infused a major shock to the world economy, nobody expects low-interest rates to leave any time soon.

Interest rates are a fundamental assumption in any financial decision. Consistently low and negative interest rates are changing the way the financial system is thinking. Economists and industry professionals have raised their concerns as we are entering unchartered waters. In this article, we will analyze the consequences of the past decade on public markets, banks, and private markets.

A View on Public Markets

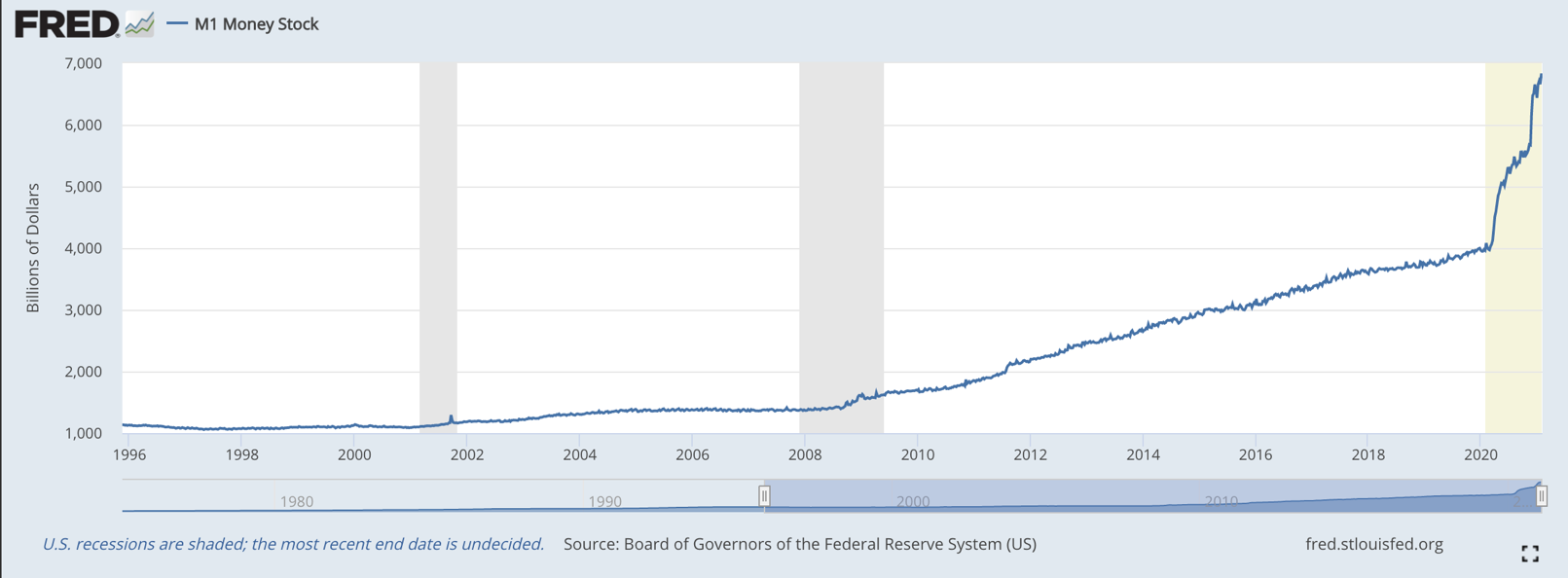

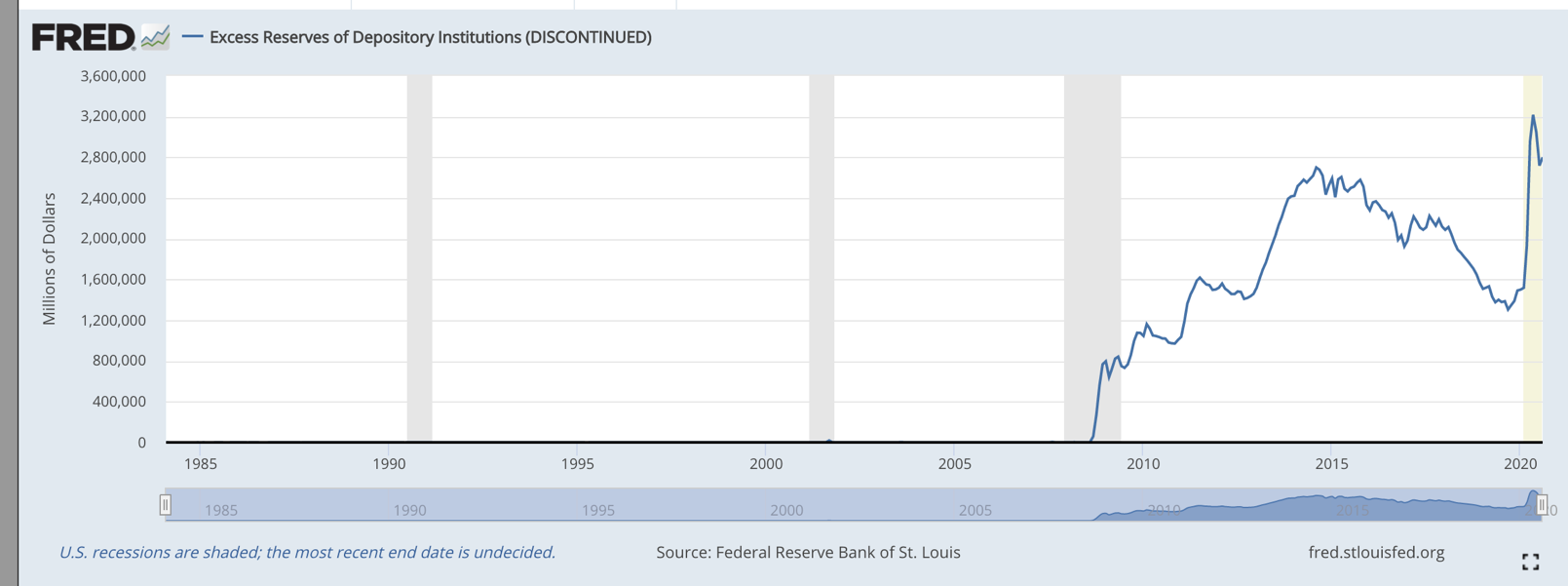

By buying large amounts of assets, the central banks infuse a lot of money into the economy. According to data published by the FED, over 35% of the real US dollars in circulation were printed in the past year. And 75% of the money supply was created after the financial crisis in 2008 (Figure 1). For the Euro area, these numbers look similar. There is also still a lot of idle money that financial institutions can disburse. As you can see in Figure 2, before 2008 the excess reserves banks had with the FED were very limited, but they exploded after the introduction of low-interest rates and Quantitative Easing. Financial institutions are eager to put this money to use as it drags on their performance.

Figure 1: Money Supply. Source: FRED

Figure 2 Excess Reserves of Banks. Source: FRED

These amounts of money are seeking a place to stay, decreasing the cost of debt and the cost of equity. Monetary stimulus is like sugar for investors as it increases the valuation of assets by solely decreasing the discount rate for future cash flows without changing the underlying asset itself. Equity investors benefit even more as the lower interest rates reduce the debt expenses and thus companies generate higher cash flows to equity. Indeed, the US-stock market has achieved abnormally high returns over the past 10 years compared to its historical values. The S&P 500 index has displayed a return of 13.6% from 2010 until 2020, while the average stock market return has averaged 9.2% over the past 140 years. Also, many companies were able to achieve important “IPO pops” and companies were able to raise record amounts of debt in 2020. This shows us that the demand for financial assets is still very strong. At the moment this demand is being filled by a relatively new asset class––Special Purpose Acquisition Companies. BSIC has explored in previous articles in more detail how these vehicles facilitate the listing of a company by reducing the regulatory requirements, but potentially at the cost of lower transparency.

Generally, as we have seen with the advent of SPACs, the oversupply of money has harmed the protection of investors. This can be also seen in the debt markets where distressed companies can get financing with very unfavorable terms for the debt-investor. For example, the use of covenants has decreased over the past years. There are much fewer restrictions on what the money can be used for. Debt is increasingly used to fund share buybacks and dividend recapitalizations. Besides, payments in kind and portable debt have become more common over the past years.

The trend of share buybacks is something that can be explored more deeply. In the past decade, US$ 5.3tn has been spent by corporations in America to buy back their shares. These buybacks are often funded through debt, and thus do not reflect real value creation. Indeed, many companies with negative free cash flow were engaging in share buybacks. The reason why companies that do not generate cash still engage in such practices are threefold:

- With low interest rates, the cost of debt is very low which allows managers to reduce their overall cost of capital by increasing the amount of debt in the capital structure

- Management incentive structures reward share buybacks because variable compensation is often based on EPS and share price metrics which could be inflated using such financial engineering

- The aforementioned lack of debtholder protection enables the use of debt to transfer value from debt investors to equity investors

Companies have been more aggressive with the use of debt in their capital structures. According to a study conducted by McKinsey & Co., the debt to EBITDA ratio has increased from 2.3x in 2008 to 3.3x in 2018 among US firms. Debt can turn extremely dangerous in case of a major downturn. The increased leverage functions as a procyclical element that could increase the effects of possible shocks. Also, the strong intervention of the FED to improve lending conditions for companies introduced a moral hazard issue for investors. The low-interest rates for junk bonds can be explained by the fact that investors expect that central banks eliminate tail-end risks, and thus invest in such assets. This then drives down interest rates even further. This creates a structural dependency on central banks that could prove a fatal flaw in the system and lead to severe risk underestimation.

Because lenders are no longer afraid of lending to distressed companies, many economists fear the phenomenon of so-called “Zombie Companies”. These are corporations that are no longer able to finance their interest payments with their operations. In Europe, they have been on top of the minds even before the pandemic. For example, according to estimates by the OECD about 20% of Italy’s capital was sunk into Zombie companies in 2013 when Europe doubled down on QE to face the sovereign debt crisis. Due to the pandemic-induced lockdowns, the share of firms with an interest coverage ratio of less than one increased globally. The only thing that keeps such companies alive is the artificially low-interest rate. Economic theory says that such companies drag on a country’s productivity in the long run. Thus, soon we might have to start to discuss and decide which companies need to fail for the good of the economy.

A view on Banks

Prolonged low interest rates have been proven to have a negative impact on banks’ profitability in the long run, and this is more significant for those institutions that are more reliant on so-called asset transformation – borrowing short-term and lending long-term – and net interest income. In fact, in the short term, low interest rates can have a positive effect on banks’ profitability, decreasing funding costs, increasing the value of fixed-rate assets and of equity, and decreasing the credit risk of borrowers. However, a prolonged period of low interest rates causes a flattening of the yield curve and consequent compression of interest rate margins for commercial banks, whose traditional activity involves the aforementioned maturity transformation. At the same time, banks face rigidity in funding rates, as it has proven extraordinarily difficult to apply negative interest rates to retail depositors, further compressing the net interest margin.

Summary of effects of low interest rates on bank business and profitability, extracted from The Bank Business Model in the Post-Covid-19 World of Elena Carletti, Stijn Claessens, Antonio Fatás and Xavier Vives.

In order to survive in this adverse environment and sustain their profitability, banks can engage in different activities. First, there is the possibility of increased risk taking in the pursuit of yield: indeed, banks can target higher risk lending segments, such as consumer finance or loans to SMEs; they can adopt laxer lending standards and they can even engage in regulatory arbitrage, investing in higher risk assets that are not perfectly recognized as such by the regulatory framework on capital adequacy. This behavior can lead to mispricing of credit risk and it can adversely affect financial stability.

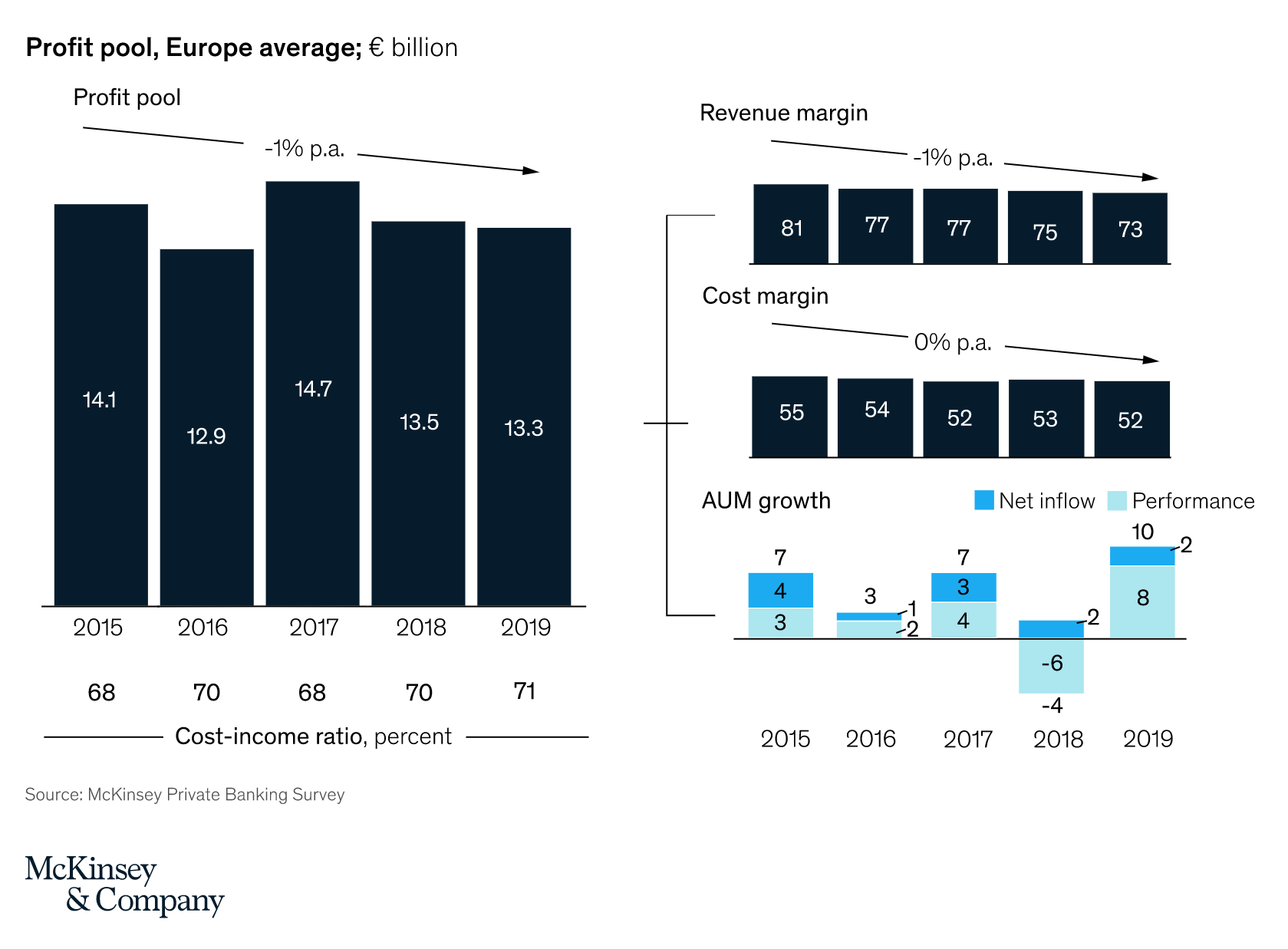

Another possibility for universal banks is to increase their fee generating activities. Indeed, activities such as wealth management and private banking are not as significantly affected by the low interest rates environment and they don’t require banks to set aside significant amounts of capital. This has caused a significant push of high profile investment in the sector by banks striving to diversify from lending and traditional investment banking, as explored in this other article by BSIC. However, the competition in this industry is becoming increasingly high, putting pressure on the commissions income. According to the McKinsey report on the future of private banking in Europe, profits have been declining in both 2019 and 2020, mainly due to costs rising faster than revenues, especially sales and marketing expenses, and this trend is set to continue even in following years, with increased costs related to investments in the digitalization of the customers’ experience and in the automation of processes.

Source: McKinsey & Company

Eventually, banks can resort to costs’ cutting to boost their profitability. Technological efficiencies will result in vast headcount reduction in the banking sector: Wells Fargo & Co estimated in a 2019 report 200,000 job cuts in the U.S. banking sector over the next decade, while in Europe lenders across this region have collectively announced more than 60,000 jobs cuts in 2019. Changing consumer habits, in particular following the Covid-19 pandemic, are also accelerating the reduction of physical branches and the shift to online banking for the majority of their services, moving from the traditional “brick and mortar” business model to one closer to fintech companies.

In this low interest rate environment, characterized by low margin activities for banks, economies of scale and scope are becoming extremely important. Banks will need to reach a large critical size in order to increase their operating efficiency and to survive in this environment; in this industry, M&A is, for several reasons, an extremely efficient way to achieve scale and gain competitive advantage. First, there is a large dispersion in valuations and capital levels across the banking system, creating an ideal environment for inorganic moves. Second, with systemic risk in banking largely mitigated through capital and liquidity build-ups since the global financial crisis, and fragmented banking sectors in many markets struggling to produce returns, regulators are more likely to be supportive of consolidation. Third, the need for large- scale investments in technological transformation, combined with weak organic growth, is pushing M&A upon the board agenda. If you wish to read more about consolidation in the banking industry, you can have a look to this other article, where BSIC analyzed in depth the merger of the Spain’s Caixa Bank and Bankia, or to this one, where BSIC explored the consolidation in the European Financial Services Sector.

In conclusion, weak banks’ profitability represents a structural problem for the entire financial system. Indeed, the profitability of banks is important for financial stability, since profits are the first line of defense against losses from credit impairment and they ensure that banks are able to provide financial services to households and businesses, even in the face of adverse developments. Furthermore, low bank profitability can also matter for monetary policy: this low profitability impairs the accumulation of bank capital over time and, therefore, it reduces the ability of monetary policy, which relies on bank lending supporting consumption and investment, to stimulate economic activity in downturns. In order to keep interest rates low and to maintain strong and healthy banks, regulators will probably support consolidation in the banking industry, as it has happened recently in Europe, for example with the combination of Italy’s Intesa Sanpaolo and Unione di Banche Italiane, and with the merger of the Spain’s Caixa Bank and of Bankia.

A view on Private Markets

Jim Barry, the CIO of BlackRock Alternatives stated in an interview that over the last ten years, alternative investments “are no longer alternative, they have become a core part of an investor’s portfolio.” The rise of alternative asset classes could partially be attributed to the resilience of these longer dated illiquid investments to fluctuating market dynamics. In Jim Barry’s words these assets are more resilient since they have less accounting volatility since no unrealized gains and losses are recorded, they are less prone to a force-selling operation, since they are insulated from market sentiment, and as a consequence of that they are less correlated with the market and can be used to hedge risk. In particular, there are a few emerging asset classes that offer low correlations but seem to guarantee interesting returns thanks to the increasing exit multiples. Some relevant examples are wind farms, Telco infrastructure or even music royalties which saw incredible rise to popularity among investors in the past 10 years.

Bringing the focus to private Equity, we have observed significant increases in the use of dividend recapitalization, a somewhat controversial practice that allows PE funds to pay dividends to yield hungry investors even before the investment in the portfolio company has been exited. This is increasingly more common and on the rise in a climate of low interest because it is fueled by cheap borrowing, as the dividends paid are fully debt-financed and pile on top of existing debt, although not being used for purposeful investments. What is worrisome is that with monetary expansion exploding again in the US this practice seems to have blown out of control. Indeed, in September 2020, approximately 25% of the money raised in the American loan market was used to fund dividends, whereas the 2018 and 2019 averages were less than 4%. The irony is that low rates have pushed entry multiples up, thus reducing potential returns, and as a consequence, in a desperate attempt to achieve higher returns they are using every gimmick possible to artificially increase the leverage beyond advisable levels.

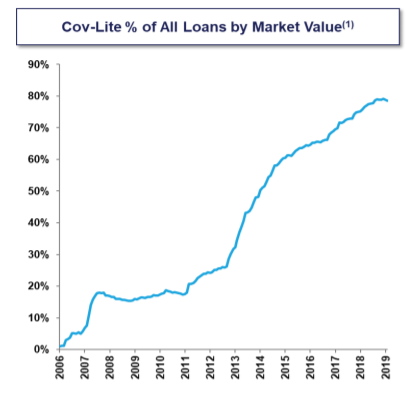

However, the most relevant issue is not the debt level per se, so much as the falling quality of debt protection. As shown in Fig. 4, that paints a bleak picture of US loan market, it is shown a dramatic increase of so-called Cov-lite loans since the beginning of QE. This term is a catch-all word to indicate lower level of creditor protections and are opposed to covenant-heavy loans, which featured maintenance or financial covenants, that are required to be tested on a periodic basis. These include tests of leverage, interest coverage, and capital expenditures, among others.

Figure 4 source: BainCapital Credit Report

Low rates are at the core of this shift, which is counterintuitively brought forward by the creditor themselves. Indeed, as creditors are pressured by low returns, they are increasingly more willing to accept lower protections and lower recovery rates in exchange for higher nominal yields. This shift goes hand in hand with the rise to prevalence of private debt funds that may opt for lower protections in combination with other governance measure such as appointing board members or providing some hybrid equity tranche.

Another key trend in the lending clauses revolves around portability. A portability clause in a loan agreement allows the borrowing company (usually owned by a private equity fund) to be sold to its new owner without the common-practice refinancing of the current debt, thus transferring it onto the new owner on the same exact terms and conditions. Traditionally, when a leveraged company is purchased, the acquirer must make new financing agreements, with a new or possibly the previous lender. However, in cases where portability clauses are present, the previous lender could lose out on the opportunity of exerting contractual power, especially in case there are new and greater risks to take into consideration after the takeover. Without a portability clause, the previous lender, if chosen to be the new lender, could demand higher interest payments, place debt covenants, or impose other conditions. On the other hand, the creditor could benefit from portability clauses if the acquisition of the company will lead to lower risks or in case of falling interest rates (however in this scenario it would be refinanced anyway).

In final analysis, low interest rates have significantly transformed the structure of the market, pushing yield hungry investors to new solutions. These transformations, however, are becoming increasingly unstable and it seems that with falling debt protection quality and wrong incentives at play, the economy at large may be on its way to complete addiction to monetary expansion policies.

BSIC Links:

- Spac the IPO killer: https://bsic.it/spacs-the-ipo-killer/

- The latest trends in IPO: https://bsic.it/booms-surges-and-battles-bsic-presents-the-latest-trends-in-ipos/

- Low-interest rates: https://bsic.it/banks-struggle-in-the-face-of-low-rates-how-to-maintain-profitability/

FT Links:

- The seeds of the next debt crisis: https://www.ft.com/content/27cf0690-5c9d-11ea-b0ab-339c2307bcd4

- Companies are dangerously drunk on debt: https://www.ft.com/content/27cf0690-5c9d-11ea-b0ab-339c2307bcd4

- Buybacks: Free cash flow didn’t always flow: https://www.ft.com/content/b3a149d2-3cff-446c-a90d-5db855520ae2

- Concern over waning use of covenants: https://www.ft.com/content/44030cb2-4690-11e5-b3b2-1672f710807b

Additional Links

- Average stock market returns https://www.businessinsider.com/personal-finance/average-stock-market-return?IR=T#:~:text=Between%202010%20and%202020%2C%20however,in%20the%20past%2010%20years.

- Figure 2: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/EXCSRESNS

- Dividends vs buybacks: https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/finance/dividend-vs-share-buyback-repurchase/

- Amount of share buybacks: https://www.marketwatch.com/story/stock-buybacks-have-totaled-53-trillion-over-the-past-decade-has-that-contributed-to-us-pandemic-failures-2020-07-29#:~:text=Stock%20buybacks%20have%20totaled%20%245.3,to%20U.S.%20pandemic%20failures%3F%20%2D%20MarketWatch

- Figure 1: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M1

- Mckinsey leverage study: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/is-a-leverage-reckoning-coming

0 Comments