Introduction

Recently, it has been impossible to ignore the troubles Credit Suisse has been facing. After three years of scandals, the bank is evaluating to break up its Investment Bank to try to leave this chapter behind. Under the proposals allegedly put forward to the board, the bank would be looking to split the division into three, seeking to have its advisory business aside under one part, keeping the remaining activities under the second, and possibly creating a ‘bad bank’ to include high-risk assets.

In recent years, other banks like UBS and Deutsche Bank have shrunk their investment banking divisions, seeking more consistent and profitable results. To understand whether Credit Suisse’s approach of shrinking the investment bank will be fruitful, we will look at how competitors that have gone through the same process faired.

Recent Examples of Banks Shrinking Their Investment Banks

In 2011, UBS announced the industry’s most drastic restructuring plan aiming at shifting its focus to its flagship Private Banking business and away from Investment Banking. Among the triggers was a $2bn rogue trading scandal that led to the CEO resigning. Further, after continuously failing to earn the bank’s cost of capital, the trading unit was set to become even less profitable with tougher upcoming capital regulations. Hence, aiming to reduce its risk-weighted assets, the bank announced that it would wind down its Fixed Income operations, focusing the Investment Banking on capital-light Equities and Foreign Exchange, and on the advisory business. In accordance with this, 10,000 employees, a sixth of the total workforce, were fired.

Led by the then recently named CEO, Sergio Ermotti, the intent was to make way for renewed growth of the Wealth Management business, and to strengthen the bank’s capital position. In the end, “boring banking” was “good banking” for UBS, which was ready to capitalize on their market-leading position in the ultra-high net worth business. Not even concerns with the then eroding Swiss secrecy, held back the bank from securing new money and follow through with the strategy.

In 2019, in efforts led by CEO Christian Sewing, Deutsche Bank announced plans to restructure its corporation by means of shrinking their Investment Bank. The bank hadn’t been able to recover from the financial crisis and had just failed to merge with Commerzbank, in a deal that would have created the second largest bank in the Eurozone. Determining that’s its operations were too complex, the group decided to close their equities sales and trading division and shrink its rates division. Due to the bank’s history of failures in the division, it was decided the risk was no longer worth taking.

The new strategy set was focused on corporate money management, a less profitable, but more reliable business. To achieve this goal, the bank announced that it was laying off over 18,000 employees, wishing to save over $6.7 bn by 2022, with a great deal of it coming from lower salary expenses and bonuses. Reportedly, the group also wished to expand its Wealth Management business, a rather small business for the bank, but reliable in the long run.

Back to Credit Suisse

Credit Suisse’s situation is somewhat similar to the one its peers faced. In 2021, its Investment Banking division alone generated a loss of almost $4bn. The bank also has failed to stay out of press, being associated to innumerous scandals. Hence, in desperate need for better results, restructuration, both of cost-oriented and strategy-oriented, are needed.

Although it is not clear what will ultimately happen to Credit Suisse Investment Banking business, a shrink of the division, and focus shift to Wealth Management similar to USB is probable. The restructuring will be costly, and, in contrast to its peers, the bank may have to rely on the market for funding while its shares trade at record low levels. According to a Deutsche Bank analysis, restructuring costs, growing other business lines, and strengthening its capital ratios could add up to a $4bn capital shortfall.

To fund this transition, the bank could announce the sale of its profitable securitized products business and other small businesses. Due to its capital-intensive nature, selling the unit valued by an expert at $1.5bn-$2.5bn could fit a possible shift towards less capital-intensive businesses as done in the past by UBS and Deutsche. Moreover, a future spin-off of the advisory business was speculated.

Further, Credit Suisse shares an advantage that UBS had. Credit Suisse is the second largest wealth manager outside the US, only trailing UBS. This means that, with a restructured business model, the bank could effectively capitalize on their leading position and expertise, with no costly barriers, in a highly profitable market.

Deutsche Bank: What actually changed?

Following Christian Sewing’s appointment as CEO, Deutsche Bank provided an example of an effective strategy involving the dismantling of a merchant bank’s Investment Banking section in Europe. A year after he took office, he unveiled his ambitious proposal to save the 152-year-old bank that has fallen a long way since the days it provided funding for Germany’s industrialization. In order to cut costs by €5.8 billion a year, a quarter of the total, to €17 billion in 2022—a goal just $2 billion short of their total expenses in 2021—he promised in 2019 that the company would undergo “the most fundamental transformation,” which included shrinking its investment bank and ceasing all share trading.

Four pillars make up Mr. Sewing’s reorganized bank, with the retail segment and investment bank continuing to be its two greatest revenue generators. After merging with Postbank, a German postal bank, in 2018, Deutsche is still the largest retail lender in the nation (the synergies are similar to those between Credit Suisse and its Swiss Bank business, the company’s top earner). More than a third of the investment bank’s relatively sizable earnings came from trading fixed-income securities, currencies, and commodities last year. The other two pillars are a corporate bank, which offers services including cash management and trade finance to mostly European enterprises, and DWS, the largest asset manager in Germany, which is owned in large part by Deutsche. Over the course of the pandemic, the effects of DB’s shift in emphasis to FICC were abundantly clear. Despite declining only 11% from the previous year, revenue of 1.8 billion euros ($2.12 billion) in 2020 was significantly lower than that of Wall Street firms, which saw reductions of almost 40% during the same period (as did European rival Barclays).

It goes without saying that Credit Suisse has recently experienced turbulent times. The well-known losses from the collapses of Greensill Capital and Archegos Capital Management resulted in a number of top management changes, very poor financial performance over the previous few quarters, and a net loss of CHF 1.65 billion in 2021 as opposed to profits of CHF 2.7 billion the year before. The bank performed (another) strategic evaluation of its operations as a result of its operations’ poor financial performance over the previous two quarters, which should be released simultaneously with the bank’s Q3 earnings in the coming days.

Source: Stockcharts.com

The company’s shares have experienced a major de-rating as a result of the market’s current environment, and they are currently trading at a depressed valuation of just 0.23x book value, a huge discount to the average for both American and European money center banking of around 1.21x. However, it is clear that the approach will take time to implement given the contrast between this and the similarly priced Deutsche Bank (whose own valuation is currently sitting at a newly achieved low of 0.22x book value). The Royal Bank of Scotland (now the NatWest Group) and UBS, who are now around 10 years out from the start and are therefore seeing 0.6x and 0.9x price to book values respectively, are significantly further advanced in their restructurings than Deutsche Bank, which has only been in motion for around 4 years. The road to redemption is long, and the market still does not trust Deutsche. The potential valuation results discussed occur over a decade, not just a few years, and Credit Suisse will confront the challenges of Deutsche to the power of 2, which is something to keep in mind when assessing Credit Suisse moving forward.

Another excellent example of an IBD drawdown that was successful is the Royal Bank of Scotland (now the NatWest Group). After the financial crisis, circa 2012, the RBS decided to taper its Investment Banking division. With the advantage of hindsight, it appears that the choice was the correct one. Putting the effort into the higher-margin divisions surrounding retail banking and asset/wealth management helped churn more profits going forward than committing hardcore to a fiercely competitive IB space, as RBS proved. This may be the case with Credit Suisse as well, but the initial hit was and will be significant, especially due to an influx of one-time costs, such as restructuring charges, impairment, and more.

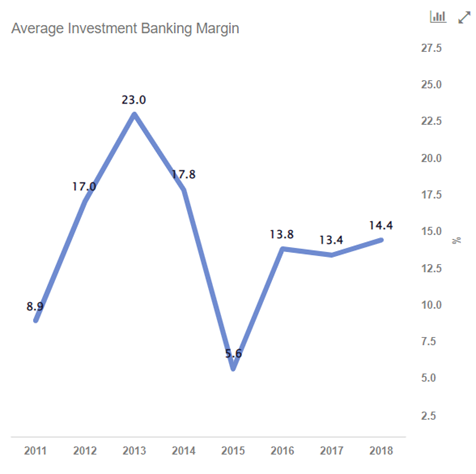

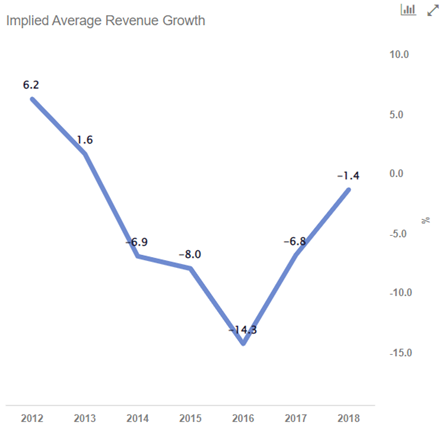

When contrasting RBS’s hypothetical revenues and EPS figures (determined by trend matching its largest competitors over a period of 6 years starting in 2012, Credit Suisse, UBS, Deutsche Bank, and Barclays), we can see that the margins would in fact have been higher if it retained its full-fledged IBD. The average revenue growth of other European banks over 2012-2018 ranged from 6.2% in 2012 to -14% in 2016. Assuming that RBS ‘s IB revenues would have moved in tandem with the historical average of other banks. Similarly, the average IB margin for these banks has ranged from 23% to 5.6% over the same time-frame.

This, however, does not tell the whole story. Over the same period the gap between these hypothetically extrapolated revenues and profits and their actual counterparts has been becoming increasingly small, and arguably in our new uncertain environment has already crossed over. RBS’s IB margin could have been much higher, providing the bank’s overall EBT margin an upward push, the bank’s EBT margin in 2017 could have actually been 22% as opposed to just 17%. Notably, though, the bank’s decision to cut down its trading activities is bearing fruit. RBS’s actual EBT margin in 2018 was 25% while if the bank wouldn’t have cut down its IB business, the margin could have been lower at 24%, And the gap would have widened due to weaker economic conditions in Europe, and the growing dominance of U.S. investment banks even across European markets. While there are other crucial decision-making factors related with RBS’s situation, specifically a sharp ramp up in regulatory capital requirements had it maintained and scaled its IBD, the data indicates that this is yet another situation in which it was certainly the right idea to transition heavily into retail.

In Credit Suisse’s case, the exogenous and endogenous factors should not be forgotten. These, which are largely reputation related, such as it battling the fallout from Archegos, the fallout from its ties with disgraced supply chain finance firm Greensill and saw chair Sir António Horta-Osório — drafted in last April in a bid to turn the bank around and clean up its image — leaving within months after breaching Covid restrictions to attend numerous sporting events in London, sticking Credit Suisse with a CHF2bn ($2.2bn) loss in the final quarter of 2021, underlining something that can at best be described as a torrid year. However, especially bearing in mind the goals it set for itself in 2021 as it shifted over $3bn away from its IBD to wealth & asset management in pursuit of a return on tangible equity of greater than 10% by 2024 (a far cry from the -15% as of Q2 2022), I believe it a necessity for the continuation of the firm.

Conclusion

The banks with the highest price-to-book, the best revenue, and the best earnings growth going forward are those who pivot. While the initial hit is hard due to lost revenues, restructuring costs and other factors, RBS in the mid-term and DB in the short term have proven the merits of a reduction both in the half sense and in nearly the full sense. Credit Suisse already entered onto this trajectory when they transferred $3bn from their IBD to AM at the onset of the last quarter of 2021, and it is not to be forgotten that the primary driver of income from within the firm comes from their ‘Swiss Bank’ retail division, and that CS has reaffirmed time and time again that their mindset is fixed on pivoting to “Wealth Management, Swiss Bank and Asset Management, supported by a transformation of the Investment Bank.” Whether this means the shuttering or just reducing is yet to be decided, but firms have shown time and time again that focusing long-term on your high-margin profit centers can help achieve strong consistent growth, and could be the golden ticket for CS out of their last few years’ internal recession.

0 Comments