Introduction

Commercial sports, from football to ice hockey, have captivated fans across the globe and it is no surprise that this has turned the heads of investors. The industry has seen ever-growing revenues coming from broadcasting rights, merchandising and sponsorship deals. Consequently, sports franchises have become an attractive target for various groups of investors. This November, Liverpool, Manchester United [MANU: NYSE] and a 15% stake in Paris Saint-Germain have been put up for sale, all of which are demanding a valuation in the billions, figures only ever seen in the American commercial sports industry. Although we have not seen the same pace of M&A activity in the North American leagues, several developments and regulations within European sports leagues make for an interesting comparison in valuation methods and business models.

European football clubs

The last twenty years have seen intense activity in the realm of football club acquisitions in Europe. Two main trends have been identified thus far: the rise of portfolio owners in football clubs and the growing interest from foreign investors.

Portfolio owners are groups who own multiple sports club assets as part of their portfolio, with City Football Group (CFG) being the biggest and owning Manchester City FC, along with ten other clubs across the globe. CFG are closely followed by Red Bull, who own nine clubs in various disciplines, including football, motorsport and ice hockey. Kroenke Sports and Entertainment also boasts a diverse portfolio spanning five sports, but Arsenal FC is their only asset outside of the USA. All in all, there are eight ownership groups that hold at least three sports club assets, either focused entirely on football, such as Vincent Tan’s portfolio, or branching out into multiple sports such as current Liverpool FC owners, the Fenway Sports Group. Excluding the clubs owned in Europe’s big six football leagues, almost 60% of the portfolios of multi-club groups are other football clubs, primarily in other smaller European leagues, such as in Belgium, Switzerland and Austria. The rationale behind owning multiple clubs across the same sport can be partially explained by the benefits derived from building a global talent acquisition and development networks.

Foreign investment in European football was sparked by the Glazer’s acquisition of Manchester United in 2003, with fifteen out of the twenty English Premier League clubs now owned by foreign individuals or institutions, predominantly from the US and the Middle East. In the last few months, we have seen US private equity group 777 Partners, who also own Genoa FC, agree to buy a majority stake in Hertha Berlin in what will be the largest foreign investment in a German football club and RedBird Capital Partners acquire AC Milan for €1.2bn – a record sale for a European football club outside of England.

Foreign investment has raised some debate surrounding the morality and nature of football clubs’ owners and their sources of wealth. These issues were brought into the spotlight during the takeover of Newcastle FC by Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who allegedly ordered the murder of Washington Post journalist, Jamal Khashoggi. These issues have led to increased legislative scrutiny, including the introduction of Owners’ and Directors’ tests and an Independent Regulator for English football.

Sports teams’ valuations have been skyrocketing in the past year, mainly due to a boom in the price of live broadcast rights. Chelsea FC was sold for £2.5bn in May following the invasion of Ukraine and Newcastle FC was sold for £300m to the Saudi Arabian Public Investment Fund last October. Along with other factors, this has led to three of Europe’s biggest football clubs to be put up for sale within a few days between each other. Fenway Sports Group are exploring the sale of Liverpool FC, the Glazers announced that Manchester United is up for sale and are looking for a fee of over £7bn, whilst Qatar Sports Investments are looking to sell a 15% stake in Paris-Saint-Germain based on a valuation of over €4bn.

Leading Investment Banks

The Raine Group is one of the leading companies in advising transactions between football clubs in Europe. Despite being based in New York City, they are currently advising the Glazers on the sale of Manchester United, had advised Roman Abramovich on the sale of Chelsea FC earlier this year and Manchester City on the sale of a stake to US private equity group Silver Lake for $500m in 2019.

Investment banks have also been unveiled as the driving force behind the financing and commercialisation of the European sports industry, with JP Morgan [JPM: NYSE] and Goldman Sachs [GS: NYSE] being the biggest players. The former was expected to provide the European Super League with a loan of €3.5bn, before the plan collapsed. JP Morgan also advised Rocco Commisso on his purchase of the Italian club ACF Fiorentina in 2019, Dan Friedkin on his takeover of AS Roma two years ago and the Glazer family on taking control of Manchester United in 2005. Goldman Sachs led the bridge financing of the $1.7bn stadium for Tottenham Hotspur and pioneered the so-called Mediaco structure for AS Roma and Inter Milan in 2017, allowing them to issue public bonds secured against their media and sponsorship rights. This is a source of funding they continue to use to this day.

North American Sports Industry Overview

Commercialisation has taken North America by storm when it comes to the “Big Four” sports leagues. This includes the NFL (National Football League), NBA (National Basketball Association), NHL (National Hockey League) and MLB (Major League Baseball). Although these are the major players it is important to note that a series of sports leagues including the MLS (Major League Soccer) and the NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association – the governing body for collegiate sports) have been the dominant leagues with rising popularity in recent years.

The distinct legal status of the professional sports leagues and the extensive media engagement are two of the most significant reasons that enabled the commercialisation of sports in the United States. The American government removed several legal constraints from professional leagues to help them survive – such as granting permission to operate as monopolies without violating antitrust regulations. The increased popularity of passive sports consumption is primarily responsible for the close relationship between TV and sport. As they can charge high prices for advertising spots, TV stations can afford to cover the broadcasting rights’ rising costs.

The well-known professional sports of American football, basketball, hockey and baseball are undoubtedly profit-driven and exhibit a surprising range of financial resources. The same applies to many Division 1 institutions in the NCAA, which significantly rely on television broadcasts to fund their sports departments. In the 19th century, a liberal mindset and significant urbanisation contributed to the development of a society that was favourable to a sports system focused on financial gain. The structure and practices of the industry are where the biggest contrasts between commercialism in the U.S. and Europe are found when analysing the sports sector.

Furthermore, the polarity concerning the treatment of young athletes accentuates the differences between the business model in American sports versus the European perspective. It wasn’t until July 1, 2021, when the NIL legislation was approved enabling collegiate athletes to profit off their name, likeability and image. Following four years of NCAA eligibility and several opportunities to extend one’s time in the association, many college athletes spanning football, basketball and baseball may end up playing up to six years of college sports, bringing in millions for the franchise they represent and until recently could not share in the profits.

A parallel is drawn when comparing the approach to young talent in Europe. Players are often bought and sign professional contracts at a young age, accentuating the flexibility they have in making decisions to sculpt their financial future – the same cannot be said for their American counterparts. Professional sports leagues are also subject to expansion in the United States, as evidenced by the NFL’s most recent expansion in 2002, with an agreed-upon price of $700m for the Houston Texans to enter the league, which adjusted for inflation is nearly $1.3bn today.

Overall, M&A activity in the North American sports industry has been increasing in minor leagues, while remaining stagnant in the “Big Four”. We have seen the formation of the PLL (Premier Lacrosse League) and an expansion of the USL (United Soccer League) to include the San Diego Loyal. In the more established leagues like the NBA & the NFL player contracts have been the key growth areas in recent years, including a record-breaking NFL contract for star quarterback Patrick Mahomes valued at $450m over ten years and a $264m Supermax contract for Center Nikola Jokic. Although expansions of leagues have not been common in the “Big four”, changes in ownership have been happening regularly. This year’s blockbuster deal came when the Walton-Penner group bought the NFL’s Denver Broncos on August 9th for $4.65bn.

Leading Investment Banks

When it comes to the leading investment banks involved in the industry, a series of New-York-City based boutiques handle matters for most of the North American Transactions. The industry leader in the field is the Inner Circle Sports LLC (ICS), which focuses on limited partnership transactions, private capital raising, sports facility financing and valuations.

Advising teams and individuals on transactions across industries spanning from the NBA, MLS, MLB and the NFL have been ICS’s main focus. Key deals they have worked on in the past include advising the Sacramento Kings limited partners on the sale of their interests in 2021, advising Jake Silverstein on the sale of his interests in the Houston Dynamo and Houston Dash in 2021 and buy-side M&A advisory to an investor group led by John Sherman on the acquisition of the Kansas City Royals franchise in 2019.

Other notable players in the industry include Accelerate Sports Inc. whose recent marquee transactions include the expansion of the CPL (Canadian Premier League) to include the Atlético Ottawa and the sale of the Arizona Coyotes in the NHL in 2019 in a deal valued at $300m.

Valuation Methods

These astronomical valuations have left many analysts scratching their heads over the value that investors see in largely unprofitable sports franchises. This begs the question: how do you value a sports team?

To value any business, there are typically two common methods that are used: a discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis and comparable company analysis. A DCF analysis determines the present value of a business by discounting all future cash flows and ultimately rests on the assumption that the company is expected to generate positive cash flows over a given period. However, in the case of sports clubs, not only are future cash flows difficult to predict as they are tied to performance on the pitch, but most sports clubs make a net loss. During the period from 2019 to 2021, only ten football clubs recorded a profit of £1m or more. With over 1,000 professional clubs in Europe, this represents less than 1% of them that were able to record a significant profit. In North America however, profitability varies across different leagues – with all teams in the NFL making an operating profit but all teams in the NHL posting a loss. Teams in the other major leagues, namely the NBA and the MLB, show mixed results, with most NBA teams having a positive operating income and half of the MLB teams making a loss.

Comparable companies and precedent transactions analysis are relative valuation methods which compare similar businesses by looking at trading multiples such as P/E and EV/EBITDA. In the case of sports teams, revenue multiples are used as a basis before looking at EBITDA or EBIT multiples, as these may be negative. However, this method still introduces a lot of subjectivity to the matter. Different clubs will be valued at different multiples depending on various factors such as brand value, fan base, stadium size and infrastructure quality. Typically, a revenue multiple of 1.5x to 2.0x is used for mid-tier Premier League clubs, whilst most clubs in Germany trade for more than 2.0x due to strong league governance and higher league revenue distribution. These multiples however are dwarfed by those of Europe’s elite clubs. If Manchester United are to be valued at £7bn, that would give them a revenue multiple just over 12.0x, meanwhile Newcastle United’s sale of €354m gives them a revenue multiple of just over 2.0x. The disparities in trading multiples of clubs within the same league is another challenge when valuing football clubs.

The trading multiples used for Europe’s top clubs are closer to those applied to clubs in North America’s professional leagues, possibly because both clubs share a near-certain guarantee against relegation – the ultimate value shredder. The less meritocratic approach taken in American sports, where the threat of being relegated or removed from a league is non-existent, leads to higher and more predictable cash flows. Additionally, all major leagues have a predetermined infrastructure for drafting future talent out of university or from teams abroad with the worse a particular team performs, the higher chance they have of being the first team to select the new class of players set to join the league. This means that poor performing teams can still expect strong cash flows due to the inflow of young talent. Consequently, North American sports franchises sell at much higher revenue multiples, between 5.5x and 6.0x, than their European counterparts.

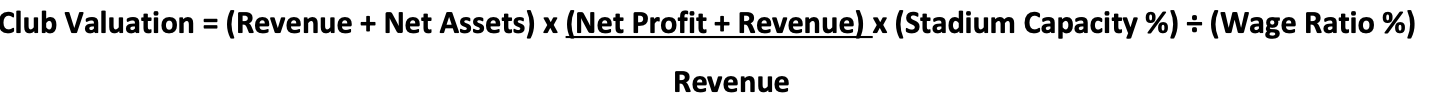

In 2013, Dr Tom Markham published the Markham Multivariate Model proposing an improved method of valuing football clubs rather than relying on the DCF or revenue multiples. The format of the model is shown below:

The model uses not only the standard business metrics such as revenue and net assets, but also football specific key performance indicators such as the stadium occupancy rates. The sum of revenue and net assets is an important factor as it helps determine the club’s current and future cash flow generation capacity and consequently makes up the backbone of the model. The model then considers the club’s profitability in comparison to its total revenue. Profitable clubs will have a figure greater than 1, hence enhancing their valuation, whilst unprofitable clubs will have a figure less than 1 and so reducing the impending valuation in line with losses. The model then multiplies by the average stadium utilisation percentage which essentially illustrates how effectively the club is using its differentiating asset. Finally, the overall figure is divided by the club’s wages to revenue ratio, which highlights the club’s ability to control its major expenditure. This model is a variation on the revenue multiple approach, with the underlying principle being that a club’s ability to make money in the future should determine its value. When the model was compared to actual club sale values between 2003 and 2013, on average the multivariate model was only 2.8% higher than actual club transaction prices – a much better result that the DCF and revenue multiples method.

The ever-changing value drivers for the sports industry must also be considered and the valuation analysis must be adjusted appropriately. For instance, because of COVID-19 effects on the sports sector, which resulted in games being played in empty stadiums, there has been a substantial shift in the consumption pattern towards Over the Top (OTT) streaming platforms. This trend has been evidenced by the NFL launching its own streaming platform, ‘NFL+’ and Amazon Prime Video offering streaming for certain English Premier League matches.

Ultimately, valuing a football club is akin to shooting arrows with a blindfold on – it is possible to shoot the target, but even the best archers are unlikely to hit the bullseye. Nobody really can say how much a club is worth, until someone ponies up a mountain of cash for it. Emotions, ego and politics play a hand in all investment decisions, but these factors are even more prominent in the sports industry. Football clubs can be seen as strategic capital and so may be bought for various political reasons. An acquisition of a high-profile club can bring great press to a company or even a country and can thus be seen as vehicles to improve a public image. For example, Manchester City and Paris Saint-Germain are often seen as ambassadors for the countries of their owners, UAE and Qatar, respectively. More recently, Saudi Arabia have been accused of sports washing when they designed Newcastle United’s third kit in the colours of their country. Owning a football club can also present a unique advertising opportunity to its owners. Mike Ashley, the former owner of Newcastle United, capitalised on the club’s advertising spaces, namely the stadium, to promote his other business, Sports Direct.

Conclusion

Although revenue multiples are the most common method used when valuing sports teams, difficulties arise when attempting to find a more intrinsic value to many associations. The key differences when valuing sports teams in North America and Europe, boils down to more predictable cash flows and higher risk protection in the North American market. In Europe we can expect to see a continued increasing involvement of portfolio owners and private equity companies investing in football clubs, potentially heading towards another attempt at a transformational event such as the European Super League proposed last year. Across the Atlantic, we anticipate higher diversification of the sports industry as the “Big Four” could lose marginal market share to growing minor leagues. Furthermore, a unification of North America as evidenced by plans of co-hosting the 2026 World Cup could be a preface for expansion teams to join major American Sports Leagues.

0 Comments